Ekman transport

Ekman transport

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

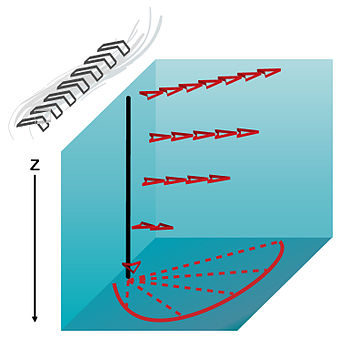

Ekman Transport is the net motion of fluid as the result of a balance between Coriolis and turbulent drag forces. In the picture above, the wind blowing North creates a surface stress and a resulting Ekman spiral is found below it in the water column.

Ekman transport, part of Ekman motion theory first investigated in 1902 by Vagn Walfrid Ekman, refers to the wind-driven net transport of the surface layer of a fluid that, due to the Coriolis effect, occurs at 90° to the direction of the surface wind. This phenomenon was first noted by Fridtjof Nansen, who recorded that ice transport appeared to occur at an angle to the wind direction during his Arctic expedition during the 1890s.[1] The direction of transport is dependent on the hemisphere: in the northern hemisphere, transport occurs at 90° clockwise from wind direction, while in the southern hemisphere it occurs at a 90° counterclockwise.[2]

Contents

1 Theory

2 Mathematical derivation

3 Applications

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 External links

Theory[edit]

Ekman theory explains the theoretical state of circulation if water currents were driven only by the transfer of momentum from the wind. In the physical world, this is difficult to observe because of the influences of many simultaneous current driving forces (for example, pressure and density gradients). Though the following theory technically applies to the idealized situation involving only wind forces, Ekman motion describes the wind-driven portion of circulation seen in the surface layer.[3][4]

Surface currents flow at a 45° angle to the wind due to a balance between the Coriolis force and the drags generated by the wind and the water.[5] If the ocean is divided vertically into thin layers, the magnitude of the velocity (the speed) decreases from a maximum at the surface until it dissipates. The direction also shifts slightly across each subsequent layer (right in the northern hemisphere and left in the southern hemisphere). This is called the Ekman spiral.[6] The layer of water from the surface to the point of dissipation of this spiral is known as the Ekman layer. If all flow over the Ekman layer is integrated, the net transportation is at 90° to the right (left) of the surface wind in the northern (southern) hemisphere.[2]

Mathematical derivation[edit]

Some assumptions of the fluid dynamics involved in the process must be made in order to simplify the process to a point where it is solvable. The assumptions made by Ekman were:[7]

- no boundaries;

- infinitely deep water;

eddy viscosity, Az{displaystyle A_{z},!}, is constant (this is only true for laminar flow. In the turbulent atmospheric and oceanic boundary layer it is a strong function of depth);

- the wind forcing is steady and has been blowing for a long time;

barotropic conditions with no geostrophic flow;- the Coriolis parameter, f{displaystyle f,!}

is kept constant.

The simplified equations for the Coriolis force in the x and y directions follow from these assumptions:

(1) 1ρ∂τx∂z=−fv,{displaystyle {frac {1}{rho }}{frac {partial tau _{x}}{partial z}}=-fv,,}

(2) 1ρ∂τy∂z=fu,{displaystyle {frac {1}{rho }}{frac {partial tau _{y}}{partial z}}=fu,,}

where τ{displaystyle tau ,!}

Integrating each equation over the entire Ekman layer:

- τx=−Myf,{displaystyle tau _{x}=-M_{y}f,,}

- τy=Mxf,{displaystyle tau _{y}=M_{x}f,,}

where

- Mx=∫0zρudz,{displaystyle M_{x}=int _{0}^{z}rho udz,,}

- My=∫0zρvdz.{displaystyle M_{y}=int _{0}^{z}rho vdz.,}

Here Mx{displaystyle M_{x},!}

In order to understand the vertical velocity structure of the water column, equations 1 and 2 can be rewritten in terms of the vertical eddy viscosity term.

- ∂τx∂z=ρAz∂2u∂z2,{displaystyle {frac {partial tau _{x}}{partial z}}=rho A_{z}{frac {partial ^{2}u}{partial z^{2}}},,!}

- ∂τy∂z=ρAz∂2v∂z2,{displaystyle {frac {partial tau _{y}}{partial z}}=rho A_{z}{frac {partial ^{2}v}{partial z^{2}}},,!}

where Az{displaystyle A_{z},!}

This gives a set of differential equations of the form

- Az∂2u∂z2=−fv,{displaystyle A_{z}{frac {partial ^{2}u}{partial z^{2}}}=-fv,,!}

- Az∂2v∂z2=fu.{displaystyle A_{z}{frac {partial ^{2}v}{partial z^{2}}}=fu.,!}

In order to solve this system of two differential equations, two boundary conditions can be applied:

(u,v)→0{displaystyle {(u,v)to 0}}as z→∞,{displaystyle {zto infty },}

- friction is equal to wind stress at the free surface (z=0{displaystyle z=0,!}

).

Things can be further simplified by considering wind blowing in the y-direction only. This means is the results will be relative to a north-south wind (although these solutions could be produced relative to wind in any other direction):[9]

(3) uE=±V0cos(π4+πDEz)exp(πDEz),vE=V0sin(π4+πDEz)exp(πDEz),{displaystyle {begin{aligned}u_{E}&=pm V_{0}cos left({frac {pi }{4}}+{frac {pi }{D_{E}}}zright)exp left({frac {pi }{D_{E}}}zright),\v_{E}&=V_{0}sin left({frac {pi }{4}}+{frac {pi }{D_{E}}}zright)exp left({frac {pi }{D_{E}}}zright),end{aligned}}}

where

uE{displaystyle u_{E},!}and vE{displaystyle v_{E},!}

represent Ekman transport in the u and v direction;

- in equation 3 the plus sign applies to the northern hemisphere and the minus sign to the southern hemisphere;

- V0=2πτyηDEρ|f|;{displaystyle V_{0}={frac {{sqrt {2}}pi tau _{yeta }}{D_{E}rho |f|}};,!}

τyη{displaystyle tau _{yeta },!}is the wind stress on the sea surface;

DE=π(2Az|f|)1/2{displaystyle D_{E}=pi left({frac {2A_{z}}{|f|}}right)^{1/2},!}is the Ekman depth (depth of Ekman layer).

By solving this at z=0, the surface current is found to be (as expected) 45 degrees to the right (left) of the wind in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere. This also gives the expected shape of the Ekman spiral, both in magnitude and direction.[9] Integrating these equations over the Ekman layer shows that the net Ekman transport term is 90 degrees to the right (left) of the wind in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere.

Applications[edit]

- Ekman transport leads to coastal upwelling, which provides the nutrient supply for some of the largest fishing markets on the planet[10] and can impact the stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet by pulling warm deep water onto the continental shelf.[11][12] Wind in these regimes blows parallel to the coast (such as along the coast of Peru, where the wind blows out of the southeast, and also in California, where it blows out of the northwest). From Ekman transport, surface water has a net movement of 90° to right of wind direction in the northern hemisphere (left in the southern hemisphere). Because the surface water flows away from the coast, the water must be replaced with water from below.[13] In shallow coastal waters, the Ekman spiral is normally not fully formed and the wind events that cause upwelling episodes are typically rather short. This leads to many variations in the extent of upwelling, but the ideas are still generally applicable.[14]

- Ekman transport is similarly at work in equatorial upwelling, where, in both hemispheres, a trade wind component towards the west causes a net transport of water towards the pole, and a trade wind component towards the east causes a net transport of water away from the pole.[10]

- On smaller scales, cyclonic winds induce Ekman transport which causes net divergence and upwelling, or Ekman suction,[10] while anti-cyclonic winds cause net convergence and downwelling, or Ekman pumping[15]

- Ekman transport is also a factor in the circulation of the ocean gyres. Ekman transport causes water to flow toward the center of the gyre in all locations, creating a sloped sea-surface, and initiating geostrophic flow (Colling p 65). Harald Sverdrup applied Ekman transport while including pressure gradient forces to develop a theory for this (see Sverdrup balance).[15] See: Garbage Patch

See also[edit]

- Ekman velocity

Notes[edit]

^ Pond & Pickard, p 101

^ ab Colling, pp 42-44

^ Colling p 44

^ Sverdrup p 228

^ Mann & Lazier p 169

^ Knauss p 124.

^ Pond & Pickard p. 106

^ Knauss p. 123

^ ab Pond & Pickard p.108

^ abc Knauss p 125

^ Anderson, R. F.; Ali, S.; Bradtmiller, L. I.; Nielsen, S. H. H.; Fleisher, M. Q.; Anderson, B. E.; Burckle, L. H. (2009-03-13). "Wind-Driven Upwelling in the Southern Ocean and the Deglacial Rise in Atmospheric CO2". Science. 323 (5920): 1443–1448. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1443A. doi:10.1126/science.1167441. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19286547..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Greene, Chad A.; Blankenship, Donald D.; Gwyther, David E.; Silvano, Alessandro; Wijk, Esmee van (2017-11-01). "Wind causes Totten Ice Shelf melt and acceleration". Science Advances. 3 (11): e1701681. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E1681G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701681. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5665591. PMID 29109976.

^ Mann & Lazier p 172

^ Colling p 43

^ ab Pond & Pickard p 295

References[edit]

- Colling, A., Ocean Circulation, Open University Course Team. Second Edition. 2001.

ISBN 978-0-7506-5278-0

- Knauss, J.A., Introduction to Physical Oceanography, Waveland Press. Second Edition. 2005.

ISBN 978-1-57766-429-1

- Mann, K.H. and Lazier J.R., Dynamics of Marine Ecosystems, Blackwell Publishing. Third Edition. 2006.

ISBN 978-1-4051-1118-8

- Pond, S. and Pickard, G. L., Introductory Dynamical Oceanography, Pergamon Press. Second edition. 1983.

ISBN 978-0-08-028728-7

- Sverdrup, K.A., Duxbury, A.C., Duxbury, A.B., An Introduction to The World's Oceans, McGraw-Hill. Eighth Edition. 2005.

ISBN 978-0-07-294555-3

External links[edit]

- What is Ekman transport ?

Categories:

- Aquatic ecology

- Oceanography

- Fluid dynamics

- Underwater diving environment

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.496","walltime":"0.685","ppvisitednodes":{"value":1940,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":93971,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":1441,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":12,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":4,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":20328,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":4,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 357.289 1 -total"," 42.79% 152.901 1 Template:Reflist"," 35.51% 126.871 2 Template:Cite_journal"," 16.79% 59.992 6 Template:Navbox"," 16.19% 57.853 5 Template:ISBN"," 11.58% 41.375 1 Template:Short_description"," 11.02% 39.357 1 Template:Pagetype"," 6.73% 24.042 5 Template:Catalog_lookup_link"," 6.35% 22.695 1 Template:Physical_oceanography"," 6.21% 22.185 1 Template:Ocean"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.166","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":4441569,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1272","timestamp":"20181026165101","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":832,"wgHostname":"mw1272"});});