Binary operation

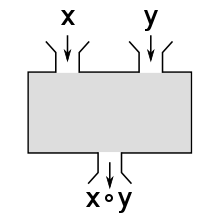

A binary operation ∘{displaystyle circ }

is a calculation that combines the arguments x{displaystyle x}

is a calculation that combines the arguments x{displaystyle x} and y{displaystyle y}

and y{displaystyle y} to x∘y{displaystyle xcirc y}

to x∘y{displaystyle xcirc y}

In mathematics, a binary operation on a set is a calculation that combines two elements of the set (called operands) to produce another element of the set. More formally, a binary operation is an operation of arity of two whose two domains and one codomain are the same set. Examples include the familiar elementary arithmetic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Other examples are readily found in different areas of mathematics, such as vector addition, matrix multiplication and conjugation in groups.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 Properties and examples

3 Notation

4 Pair and tuple

5 Binary operations as ternary relations

6 External binary operations

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 External links

Terminology

More precisely, a binary operation on a set S is a map which sends elements of the Cartesian product S × S to S:[1][2][3]

- f:S×S→S.{displaystyle ,fcolon Stimes Srightarrow S.}

Because the result of performing the operation on a pair of elements of S is again an element of S, the operation is called a closed binary operation on S (or sometimes expressed as having the property of closure).[4] If f is not a function, but is instead a partial function, it is called a partial binary operation. For instance, division of real numbers is a partial binary operation, because one can't divide by zero: a/0 is not defined for any real a. Note however that both in algebra and model theory the binary operations considered are defined on all of S × S.

Sometimes, especially in computer science, the term is used for any binary function.

Binary operations are the keystone of algebraic structures studied in abstract algebra: they are essential in the definitions of groups, monoids, semigroups, rings, and more. Most generally, a magma is a set together with some binary operation defined on it.

Properties and examples

Typical examples of binary operations are the addition (+) and multiplication (×) of numbers and matrices as well as composition of functions on a single set.

For instance,

- On the set of real numbers R, f(a, b) = a + b is a binary operation since the sum of two real numbers is a real number.

- On the set of natural numbers N, f(a, b) = a + b is a binary operation since the sum of two natural numbers is a natural number. This is a different binary operation than the previous one since the sets are different.

- On the set M(2,2) of 2 × 2 matrices with real entries, f(A, B) = A + B is a binary operation since the sum of two such matrices is another 2 × 2 matrix.

- On the set M(2,2) of 2 × 2 matrices with real entries, f(A, B) = AB is a binary operation since the product of two such matrices is another 2 × 2 matrix.

- For a given set C, let S be the set of all functions h : C → C. Define f : S × S → S by f(h1, h2)(c) = h1 ∘ h2 (c) = h1(h2(c)) for all c ∈ C, the composition of the two functions h1 and h2 in S. Then f is a binary operation since the composition of the two functions is another function on the set C (that is, a member of S).

Many binary operations of interest in both algebra and formal logic are commutative, satisfying f(a, b) = f(b, a) for all elements a and b in S, or associative, satisfying f(f(a, b), c) = f(a, f(b, c)) for all a, b and c in S. Many also have identity elements and inverse elements.

The first three examples above are commutative and all of the above examples are associative.

On the set of real numbers R, subtraction, that is, f(a, b) = a − b, is a binary operation which is not commutative since, in general, a − b ≠ b − a. It is also not associative, since, in general, a − (b − c) ≠ (a − b) − c; for instance, 1 − (2 − 3) = 2 but (1 − 2) − 3 = −4.

On the set of natural numbers N, the binary operation exponentiation, f(a,b) = ab, is not commutative since, in general, ab ≠ ba and is also not associative since f(f(a, b), c) ≠ f(a, f(b, c)). For instance, with a = 2, b = 3 and c = 2, f(23,2) = f(8,2) = 82 = 64, but f(2,32) = f(2,9) = 29 = 512. By changing the set N to the set of integers Z, this binary operation becomes a partial binary operation since it is now undefined when a = 0 and b is any negative integer. For either set, this operation has a right identity (which is 1) since f(a, 1) = a for all a in the set, which is not an identity (two sided identity) since f(1, b) ≠ b in general.

Division (/), a partial binary operation on the set of real or rational numbers, is not commutative or associative. Tetration (↑↑), as a binary operation on the natural numbers, is not commutative or associative and has no identity element.

Notation

Binary operations are often written using infix notation such as a ∗ b, a + b, a · b or (by juxtaposition with no symbol) ab rather than by functional notation of the form f(a, b). Powers are usually also written without operator, but with the second argument as superscript.

Binary operations sometimes use prefix or (probably more often) postfix notation, both of which dispense with parentheses. They are also called, respectively, Polish notation and reverse Polish notation.

Pair and tuple

A binary operation, ab, depends on the ordered pair (a, b) and so (ab)c (where the parentheses here mean first operate on the ordered pair (a, b) and then operate on the result of that using the ordered pair ((ab), c)) depends in general on the ordered pair ((a, b), c). Thus, for the general, non-associative case, binary operations can be represented with binary trees.

However:

- If the operation is associative, (ab)c = a(bc), then the value of (ab)c depends only on the tuple (a, b, c).

- If the operation is commutative, ab = ba, then the value of (ab)c depends only on { {a, b}, c}, where braces indicate multisets.

- If the operation is both associative and commutative then the value of (ab)c depends only on the multiset {a, b, c}.

- If the operation is associative, commutative and idempotent, aa = a, then the value of (ab)c depends only on the set {a, b, c}.

Binary operations as ternary relations

A binary operation f on a set S may be viewed as a ternary relation on S, that is, the set of triples (a, b, f(a,b)) in S × S × S for all a and b in S.

External binary operations

An external binary operation is a binary function from K × S to S. This differs from a binary operation in the strict sense in that K need not be S; its elements come from outside.

An example of an external binary operation is scalar multiplication in linear algebra. Here K is a field and S is a vector space over that field.

An external binary operation may alternatively be viewed as an action; K is acting on S.

Note that the dot product of two vectors is not a binary operation, external or otherwise, as it maps from S × S to K, where K is a field and S is a vector space over K.

See also

- Truth table#Binary operations

- Iterated binary operation

- Operator (programming)

- Ternary operation

- Unary operation

Notes

^ Rotman 1973, pg. 1

^ Hardy & Walker 2002, pg. 176, Definition 67

^ Fraleigh 1976, pg. 10

^ Hall, Jr. 1959, pg. 1

References

Fraleigh, John B. (1976), A First Course in Abstract Algebra (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-01984-1.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Hall, Jr., Marshall (1959), The Theory of Groups, New York: Macmillan

Hardy, Darel W.; Walker, Carol L. (2002), Applied Algebra: Codes, Ciphers and Discrete Algorithms, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-067464-8

Rotman, Joseph J. (1973), The Theory of Groups: An Introduction (2nd ed.), Boston: Allyn and Bacon

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Binary Operation". MathWorld.