Nasopharynx cancer

| Nasopharynx cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a lymph node | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

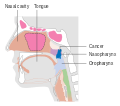

Nasopharynx cancer or nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common cancer originating in the nasopharynx, most commonly in the postero-lateral nasopharynx or pharyngeal recess or 'Fossa of Rosenmüller' accounting for 50% cases. NPC occurs in children and adults. NPC differs significantly from other cancers of the head and neck in its occurrence, causes, clinical behavior, and treatment. It is vastly more common in certain regions of East Asia and Africa than elsewhere, with viral, dietary and genetic factors implicated in its causation. It is most common in males. It is a squamous cell carcinoma of an undifferentiated type. Squamous epithelial cells are a flat type of cell found in the skin and the membranes that line some body cavities. Differentiation means how different the cancer cells are from normal cells. Undifferentiated cells are cells that do not have their mature features or functions.

Contents

1 Signs and symptoms

2 Causes

3 Diagnosis

3.1 Classification

3.2 Staging

4 Treatment

5 Epidemiology

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Signs and symptoms

Swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck is the initial presentation in many people, and the diagnosis of NPC is often made by lymph node biopsy. Signs and symptoms related to the primary tumor include trismus, pain, otitis media, nasal regurgitation due to paresis (loss of or impaired movement) of the soft palate, hearing loss and cranial nerve palsy (paralysis). Larger growths may produce nasal obstruction or bleeding and a "nasal twang". Metastatic spread may result in bone pain or organ dysfunction. Rarely, a paraneoplastic syndrome of osteoarthropathy (diseases of joints and bones) may occur with widespread disease.

Causes

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is caused by a combination of factors: viral, environmental influences, and heredity.[1] The viral influence is associated with infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).[2][3] The Epstein-Barr virus is one of the most common viruses. 95% of all people in the U.S. are exposed to this virus by the time they are 30–40 years old. The World Health Organization does not have set preventative measures for this virus because it is so easily spread and is worldwide. Very rarely does Epstein-Barr virus lead to cancer, which suggests a variety of influencing factors. Other likely causes include genetic susceptibility, consumption of food (in particular salted fish)[4] containing carcinogenic volatile nitrosamines.[5] Various mutations that activate NF-κB signalling have been reported in almost half of NPC cases investigated.[6]

The association between Epstein-Barr virus and nasopharyngeal carcinoma is unequivocal in World Health Organization (WHO) types II and III tumors but less well-established for WHO type I (WHO-I) NPC, where preliminary evaluation has suggested that human papillomavirus HPV may be associated.[7] EBV DNA was detectable in the blood plasma samples of 96% of patients with non-keratinizing NPC, compared with only 7% in controls.[3] The detection of nuclear antigen associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBNA) and viral DNA in NPC type 2 and 3, has revealed that EBV can infect epithelial cells and is associated with their transformation. The cause of NPC (particularly the endemic form) seems to follow a multi-step process, in which EBV, ethnic background, and environmental carcinogens all seem to play an important role. More importantly, EBV DNA levels appear to correlate with treatment response and may predict disease recurrence, suggesting that they may be an independent indicator of prognosis. The mechanism by which EBV alters nasopharyngeal cells is being elucidated[8] to provide a rational therapeutic target.[8]

Diagnosis

Classification

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, commonly known as nasopharyngeal cancer, is classified as a malignant neoplasm, or cancer, arising from the mucosal epithelium of the nasopharynx, most often within the lateral nasopharyngeal recess or fossa of Rosenmüller (a recess behind the entrance of the eustachian tube opening). The World Health Organization classifies nasopharyngeal carcinoma in three types. Type 1 (I) is keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Type 2a (II) is non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Type 2b (III) is undifferentiated carcinoma.[9] Type 2b (III) nonkeratinizing undifferentiated form also known as lymphoepithelioma is most common, and is most strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection of the cancerous cells.[10]

Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma—low power

Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma—med. power

Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma—high power

Staging

FDG-PET/CT scan of a patient with nasopharyngeal cancer. Transverse slice demonstrating FDG-positive primary site

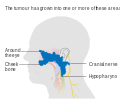

Staging of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is based on clinical and radiologic examination. Most patients present with Stage III or IV disease.

Stage I is a small tumor confined to nasopharynx.

Stage II is a tumor extending in the local area, or that with any evidence of limited neck (nodal) disease.

Stage III is a large tumor with or without neck disease, or a tumor with bilateral neck disease.

Stage IV is a large tumor involving intracranial or infratemporal regions, an extensive neck disease, and/or any distant metastasis.

[11]

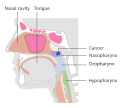

Stage T1 nasopharyngeal cancer

Stage T2 nasopharyngeal cancer

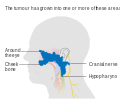

Stage T3 nasopharyngeal cancer

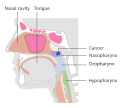

Stage T4 nasopharyngeal cancer

Treatment

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma can be treated by surgery, by chemotherapy, or by radiotherapy.[12] There are different forms of radiation therapy, including 3D conformal radiation therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, particle beam therapy and brachytherapy, which are commonly used in the treatments of cancers of the head and neck. The expression of EBV latent proteins within undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma can be potentially exploited for immune-based therapies.[13]

Epidemiology

Nasopharynx cancer as of 2010 resulted in 65,000 deaths globally up from 45,000 in 1990.[14]

NPC is uncommon in the United States and most other nations, representing less than 1 case per 100,000 in most populations.[2] but is extremely common in southern regions of China,[15] particularly in Guangdong, accounting for 18% of all cancers in China.[5] It is sometimes referred to as Cantonese cancer because it occurs in about 25 cases per 100,000 people in this region, 25 times higher than the rest of the world.[5] It is also quite common in Taiwan.[5] This could be due to the Southeast Asian diet[5] or that Southern Chinese people such as the Cantonese and Taiwanese have Southeast Asian ancestry (such as the proto-Kra-Dai speaking peoples and proto-Austronesian peoples) via ancient intermarriages with Han Chinese from Northeast Asia which led to the transmission of a genetic risk for nasopharynx cancer.[16] While NPC is seen primarily in middle-aged persons in Asia, a high proportion of African cases appear in children. The cause of increased risk for NPC in these endemic regions is not clear.[10] In low-risk populations, such as in the United States, a bimodal peak is observed. The first peak occurs in late adolescence/early adulthood (ages 15–24 years), followed by a second peak later in life (ages 65–79 years).

See also

Baseball player Babe Ruth died from nasopharyngeal carcinoma in 1948.- Endoscopic nasopharyngectomy

- Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

References

^ Zhang, F.; Zhang, J. (1999). "Clinical hereditary characteristics in nasopharyngeal carcinoma through Ye-Liang's family cluster". Chinese Medical Journal. 112 (2): 185–7. PMID 11593591..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR): Viral cancers". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

[dead link]

^ ab Lo, Kwok-Wai; Chung, Grace Tin-Yun; To, Ka-Fai (2012). "Deciphering the molecular genetic basis of NPC through molecular, cytogenetic, and epigenetic approaches". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 22 (2): 79–86. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.011. PMID 22245473.

^ Yu, M. C.; Ho, J. H.; Lai, S. H.; Henderson, B. E. (1986). "Cantonese-style salted fish as a cause of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Report of a case-control study in Hong Kong". Cancer Research. 46 (2): 956–61. PMID 3940655.

^ abcde Chang, E. T.; Adami, H.-O. (2006). "The Enigmatic Epidemiology of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (10): 1765–1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. PMID 17035381.

^ Li, Yvonne Y.; Chung, Grace T. Y.; Lui, Vivian W. Y.; To, Ka-Fai; Ma, Brigette B. Y.; Chow, Chit; Woo, John K, S.; Yip, Kevin Y.; Seo, Jeongsun; Hui, Edwin P.; Mak, Michael K. F.; Rusan, Maria; Chau, Nicole G.; Or, Yvonne Y. Y.; Law, Marcus H. N.; Law, Peggy P. Y.; Liu, Zoey W. Y.; Ngan, Hoi-Lam; Hau, Pok-Man; Verhoeft, Krista R.; Poon, Peony H. Y.; Yoo, Seong-Keun; Shin, Jong-Yeon; Lee, Sau-Dan; Lun, Samantha W. M.; Jia, Lin; Chan, Anthony W. H.; Chan, Jason Y. K.; Lai, Paul B. S.; et al. (2017). "Exome and genome sequencing of nasopharynx cancer identifies NF-κB pathway activating mutations". Nature Communications. 8: 14121. doi:10.1038/ncomms14121. PMC 5253631. PMID 28098136.

^ Lo, Emily J.; Bell, Diana; Woo, Jason S.; Li, Guojun; Hanna, Ehab Y.; El-Naggar, Adel K.; Sturgis, Erich M. (2010). "Human papillomavirus and WHO type I nasopharyngeal carcinoma". The Laryngoscope. 120 (10): 1990–1997. doi:10.1002/lary.21089. PMC 4212520. PMID 20824783.

^ ab Lo, Angela Kwok-Fung; Lo, Kwok-Wai; Ko, Chun-Wai; Young, Lawrence S.; Dawson, Christopher W. (2013). "Inhibition of the LKB1-AMPK pathway by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1 promotes proliferation and transformation of human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells". The Journal of Pathology. 230 (3): 336–346. doi:10.1002/path.4201. PMID 23592276.

^ Cummings Otolaryngology (5th ed.). 2010. p. 1344.

^ ab Cote, Richard; Suster, Saul; Weiss, Lawrence (2002). Weidner, Noel, ed. Modern Surgical Pathology. London: W B Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-7253-3.

[page needed]

^ AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th ed.). New York, NY: Springer. 2010. pp. 41–56.

^ Brennan, Bernadette (2006). "Nasopharyngeal carcinoma". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 1: 23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-23. PMC 1559589. PMID 16800883.

^ Khanna, Rajiv; Moss, Denis; Gandhi, Maher (2005). "Technology Insight: Applications of emerging immunotherapeutic strategies for Epstein–Barr virus-associated malignancies". Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2 (3): 138–149. doi:10.1038/ncponc0107. PMID 16264907.

^ Lozano, Rafael; Naghavi, Mohsen; Foreman, Kyle; Lim, Stephen; Shibuya, Kenji; Aboyans, Victor; Abraham, Jerry; Adair, Timothy; Aggarwal, Rakesh; Ahn, Stephanie Y.; Almazroa, Mohammad A.; Alvarado, Miriam; Anderson, H Ross; Anderson, Laurie M.; Andrews, Kathryn G.; Atkinson, Charles; Baddour, Larry M.; Barker-Collo, Suzanne; Bartels, David H.; Bell, Michelle L.; Benjamin, Emelia J.; Bennett, Derrick; Bhalla, Kavi; Bikbov, Boris; Abdulhak, Aref Bin; Birbeck, Gretchen; Blyth, Fiona; Bolliger, Ian; Boufous, Soufiane; et al. (2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". The Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

^ Fang, Weiyi; Li, Xin; Jiang, Qingping; Liu, Zhen; Yang, Huiling; Wang, Shuang; Xie, Siming; Liu, Qiuzhen; Liu, Tengfei; Huang, Jing; Xie, Weibing; Li, Zuguo; Zhao, Yingdong; Wang, Ena; Marincola, Francesco M.; Yao, Kaitai (2008). "Transcriptional patterns, biomarkers and pathways characterizing nasopharyngeal carcinoma of Southern China". Journal of Translational Medicine. 6: 32. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-6-32. PMC 2443113. PMID 18570662.

^ Wee, J. T.; Ha, T. C.; Loong, S. L.; Qian, C. N. (2010). "Is nasopharyngeal cancer really a "Cantonese cancer"?". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 29 (5): 517–26. PMID 20426903.

External links

| Classification | D

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- Cancer Management Handbook: Head and Neck Tumors

- Clinically reviewed nasopharyngeal cancer information for patients from Cancer Research UK