B vitamins

B vitamins are a class of water-soluble vitamins that play important roles in cell metabolism. Though these vitamins share similar names, they are chemically distinct compounds that often coexist in the same foods. In general, dietary supplements containing all eight are referred to as a vitamin B complex. Individual B vitamin supplements are referred to by the specific number or name of each vitamin: B1 = thiamine, B2 = riboflavin, B3 = niacin, etc. Some are better known by name than number: niacin, pantothenic acid, biotin and folate.

Each B vitamin is either a cofactor (generally a coenzyme) for key metabolic processes or is a precursor needed to make one.

Contents

1 List of B vitamins

2 B vitamin molecular functions

3 B vitamin deficiency

4 B vitamin side effects

5 B vitamin sources

6 B vitamin discovery dates

7 Related compounds

8 References

List of B vitamins

| B number | Name | Thumbnail description |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 | thiamine | A coenzyme in the catabolism of sugars and amino acids. |

| Vitamin B2 | riboflavin | A precursor of cofactors called FAD and FMN, which are needed for flavoprotein enzyme reactions, including activation of other vitamins |

| Vitamin B3 | niacin (nicotinic acid), nicotinamide riboside | A precursor of coenzymes called NAD and NADP, which are needed in many metabolic processes. |

| Vitamin B5 | pantothenic acid | A precursor of coenzyme A and therefore needed to metabolize many molecules. |

| Vitamin B6 | pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine | A coenzyme in many enzymatic reactions in metabolism. |

| Vitamin B7 | biotin | A coenzyme for carboxylase enzymes, needed for synthesis of fatty acids and in gluconeogenesis. |

| Vitamin B9 | folate | A precursor needed to make, repair, and methylate DNA; a cofactor in various reactions; especially important in aiding rapid cell division and growth, such as in infancy and pregnancy. |

| Vitamin B12 | various cobalamins; commonly cyanocobalamin or methylcobalamin in vitamin supplements | A coenzyme involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body, especially affecting DNA synthesis and regulation, but also fatty acid metabolism and amino acid metabolism. |

Note: other substances once thought to be vitamins were given numbers in the B-vitamin numbering scheme, but were subsequently discovered to be either not essential for life or manufactured by the body, thus not meeting the two essential qualifiers for a vitamin. See section #Related compounds for numbers 4, 8, 10, 11, and others.

B vitamin molecular functions

| Vitamin | Name | Structure | Molecular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 | thiamine |  | Thiamine plays a central role in the release of energy from carbohydrates. It is involved in RNA and DNA production, as well as nerve function. Its active form is a coenzyme called thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), which takes part in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl coenzyme A in metabolism.[1] |

| Vitamin B2 | riboflavin |  | Riboflavin is involved in release of energy in the electron transport chain, the citric acid cycle, as well as the catabolism of fatty acids (beta oxidation).[2][unreliable medical source?] |

| Vitamin B3 | niacin |  | Niacin is composed of two structures: nicotinic acid and nicotinamide. There are two co-enzyme forms of niacin: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP). Both play an important role in energy transfer reactions in the metabolism of glucose, fat and alcohol.[3] NAD carries hydrogens and their electrons during metabolic reactions, including the pathway from the citric acid cycle to the electron transport chain. NADP is a coenzyme in lipid and nucleic acid synthesis.[4] |

| Vitamin B5 | pantothenic acid | Pantothenic acid is involved in the oxidation of fatty acids and carbohydrates. Coenzyme A, which can be synthesised from pantothenic acid, is involved in the synthesis of amino acids, fatty acids, ketone bodies, cholesterol,[5] phospholipids, steroid hormones, neurotransmitters (such as acetylcholine), and antibodies.[6] | |

| Vitamin B6 | pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine |  | The active form pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) (depicted) serves as a cofactor in many enzyme reactions mainly in amino acid metabolism including biosynthesis of neurotransmitters. |

| Vitamin B7 | biotin |  | Biotin plays a key role in the metabolism of lipids, proteins and carbohydrates. It is a critical co-enzyme of four carboxylases: acetyl CoA carboxylase, which is involved in the synthesis of fatty acids from acetate; pyruvate CoA carboxylase, involved in gluconeogenesis; β-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase, involved in the metabolism of leucine; and propionyl CoA carboxylase, which is involved in the metabolism of energy, amino acids and cholesterol.[7] |

| Vitamin B9 | folate | Folate acts as a co-enzyme in the form of tetrahydrofolate (THF), which is involved in the transfer of single-carbon units in the metabolism of nucleic acids and amino acids. THF is involved in pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis, so is needed for normal cell division, especially during pregnancy and infancy, which are times of rapid growth. Folate also aids in erythropoiesis, the production of red blood cells.[8] | |

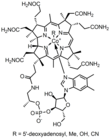

| Vitamin B12 | cobalamin |  | Vitamin B12 is involved in the cellular metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and lipids. It is essential in the production of blood cells in bone marrow, and for nerve sheaths and proteins.[9] Vitamin B12 functions as a co-enzyme in intermediary metabolism for the methionine synthase reaction with methylcobalamin, and the methylmalonyl CoA mutase reaction with adenosylcobalamin.[10][not in citation given] |

B vitamin deficiency

Several named vitamin deficiency diseases may result from the lack of sufficient B vitamins. Deficiencies of other B vitamins result in symptoms that are not part of a named deficiency disease.

| Vitamin | Name | Deficiency effects |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 | thiamine | Deficiency causes beriberi. Symptoms of this disease of the nervous system include weight loss, emotional disturbances, Wernicke encephalopathy (impaired sensory perception), weakness and pain in the limbs, periods of irregular heartbeat, and edema (swelling of bodily tissues). Heart failure and death may occur in advanced cases. Chronic thiamin deficiency can also cause alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome, an irreversible dementia characterized by amnesia and compensatory confabulation. |

| Vitamin B2 | riboflavin | Deficiency causes ariboflavinosis. Symptoms may include cheilosis (cracks in the lips), high sensitivity to sunlight, angular cheilitis, glossitis (inflammation of the tongue), seborrheic dermatitis or pseudo-syphilis (particularly affecting the scrotum or labia majora and the mouth), pharyngitis (sore throat), hyperemia, and edema of the pharyngeal and oral mucosa. |

| Vitamin B3 | niacin | Deficiency, along with a deficiency of tryptophan causes pellagra. Symptoms include aggression, dermatitis, insomnia, weakness, mental confusion, and diarrhea. In advanced cases, pellagra may lead to dementia and death (the 3(+1) D's: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death). |

| Vitamin B5 | pantothenic acid | Deficiency can result in acne and paresthesia, although it is uncommon. |

| Vitamin B6 | pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine | Deficiency causes seborrhoeic dermatitis-like eruptions, pink eye and neurological symptoms (e.g. epilepsy) |

| Vitamin B7 | biotin | Deficiency does not typically cause symptoms in adults but may lead to impaired growth and neurological disorders in infants. Multiple carboxylase deficiency, an inborn error of metabolism, can lead to biotin deficiency even when dietary biotin intake is normal. |

| Vitamin B9 | folic acid | Deficiency results in a macrocytic anemia, and elevated levels of homocysteine. Deficiency in pregnant women can lead to birth defects. |

| Vitamin B12 | cobalamin | Deficiency results in a macrocytic anemia, elevated methylmalonic acid and homocysteine, peripheral neuropathy, memory loss and other cognitive deficits. It is most likely to occur among elderly people, as absorption through the gut declines with age; the autoimmune disease pernicious anemia is another common cause. It can also cause symptoms of mania and psychosis. In rare extreme cases, paralysis can result. |

B vitamin side effects

Because water-soluble B vitamins are eliminated in the urine, taking large doses of certain B vitamins usually only produces transient side-effects. General side effects may include restlessness, nausea and insomnia. These side-effects are almost always caused by dietary supplements and not foodstuffs.

| Vitamin | Name | Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) | Harmful effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 | thiamine | None[11] | No known toxicity from oral intake. There are some reports of anaphylaxis caused by high-dose thiamin injections into the vein or muscle. However, the doses were greater than the quantity humans can physically absorb from oral intake.[11] |

| Vitamin B2 | riboflavin | None.[12] | No evidence of toxicity based on limited human and animal studies. The only evidence of adverse effects associated with riboflavin comes from in vitro studies showing the production of reactive oxygen species (free radicals) when riboflavin was exposed to intense visible and UV light.[12] |

| Vitamin B3 | niacin | U.S. UL = 35 mg as a dietary supplement[13] | Intake of 3000 mg/day of nicotinamide and 1500 mg/day of nicotinic acid are associated with nausea, vomiting, and signs and symptoms of liver toxicity. Other effects may include glucose intolerance, and (reversible) ocular effects. Additionally, the nicotinic acid form may cause vasodilatory effects, also known as flushing, including redness of the skin, often accompanied by an itching, tingling, or mild burning sensation, which is also often accompanied by pruritus, headaches, and increased intracranial blood flow, and occasionally accompanied by pain.[13] Medical practitioners prescribe recommended doses up to 2000 mg per day of niacin in either immediate-release or slow-release formats, to lower plasma triglycerides and low-density lipiprotein cholesterol.[14] |

| Vitamin B5 | pantothenic acid | None | No toxicity known |

| Vitamin B6 | pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine | U.S. UL = 100 mg/day; EU UL = 25 mg/day | |

| Vitamin B7 | biotin | None | No toxicity known |

| Vitamin B9 | folic acid | 1 mg/day[15] | Masks B12 deficiency, which can lead to permanent neurological damage[15] |

| Vitamin B12 | cobalamin | None established.[16] | Skin and spinal lesions. Acne-like rash [causality is not conclusively established].[16][17] |

B vitamin sources

B vitamins are found in highest abundance in meat. They are also found in small quantities in whole unprocessed carbohydrate based foods. Processed carbohydrates such as sugar and white flour tend to have lower B vitamin than their unprocessed counterparts. For this reason, it is required by law in many countries (including the United States) that the B vitamins thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and folic acid be added back to white flour after processing. This is sometimes called "Enriched Flour" on food labels. B vitamins are particularly concentrated in meat such as turkey, tuna and liver.[18] Good sources for B vitamins include legumes (pulses or beans), whole grains, potatoes, bananas, chili peppers, tempeh, nutritional yeast, brewer's yeast, and molasses. Although the yeast used to make beer results in beers being a source of B vitamins,[19] their bioavailability ranges from poor to negative as drinking ethanol inhibits absorption of thiamine (B1),[20][21] riboflavin (B2),[22] niacin (B3),[23] biotin (B7),[24] and folic acid (B9).[25][26] In addition, each of the preceding studies further emphasizes that elevated consumption of beer and other alcoholic beverages results in a net deficit of those B vitamins and the health risks associated with such deficiencies.

The B12 vitamin is not abundantly available from plant products,[27] making B12 deficiency a legitimate concern for vegans. Manufacturers of plant-based foods will sometimes report B12 content, leading to confusion about what sources yield B12. The confusion arises because the standard US Pharmacopeia (USP) method for measuring the B12 content does not measure the B12 directly. Instead, it measures a bacterial response to the food. Chemical variants of the B12 vitamin found in plant sources are active for bacteria, but cannot be used by the human body. This same phenomenon can cause significant over-reporting of B12 content in other types of foods as well.[28]

A popular way of increasing one's vitamin B intake is through the use of dietary supplements. B vitamins are commonly added to energy drinks, many of which have been marketed with large amounts of B vitamins[29] with claims that this will cause the consumer to "sail through your day without feeling jittery or tense."[29] Some nutritionists have been critical of these claims, pointing out for instance that while B vitamins do "help unlock the energy in foods," most Americans acquire the necessary amounts easily in their diets.[29]

Because they are soluble in water, excess B vitamins are generally readily excreted, although individual absorption, use and metabolism may vary…"[29] The elderly and athletes may need to supplement their intake of B12 and other B vitamins due to problems in absorption and increased needs for energy production.[medical citation needed] In cases of severe deficiency, B vitamins, especially B12, may also be delivered by injection to reverse deficiencies.[30][unreliable medical source?] Both type 1 and type 2 diabetics may also be advised to supplement thiamine based on high prevalence of low plasma thiamine concentration and increased thiamine clearance associated with diabetes.[31] Also, Vitamin B9 (folic acid) deficiency in early embryo development has been linked to neural tube defects. Thus, women planning to become pregnant are usually encouraged to increase daily dietary folic acid intake and/or take a supplement.[32]

B vitamin discovery dates

| B number | Name | Thumbnail description |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B1 | thiamine | Casimir Funk discovered thiamine in 1912. |

| Vitamin B2 | riboflavin | D.T. Smith and E.G. Hendrick discovered riboflavin in 1926. Max Tishler invented methods for synthesizing it. |

| Vitamin B3 | niacin or nicotinic acid | Conrad Elvehjem discovered niacin in 1937. |

| Vitamin B5 | pantothenic acid | Roger J. Williams discovered pantothenic acid in 1933. |

| Vitamin B6 | pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine | Paul Gyorgy discovered vitamin B6 in 1934. |

| Vitamin B7 | biotin | Dean Burk was a codiscoverer of biotin. |

| Vitamin B9 | folic acid | Lucy Wills discovered folic acid in 1933. |

| Vitamin B12 | various cobalamins; commonly cyanocobalamin or methylcobalamin in vitamin supplements | Various scientists over several decades developed our knowledge of vitamin B12. |

Related compounds

Many of the following substances have been referred to as vitamins as they were once believed to be vitamins. They are no longer considered as such, and the numbers that were assigned to them now form the "gaps" in the true series of B-complex vitamins described above (e.g., there is no vitamin B4). Some of them, though not essential to humans, are essential in the diets of other organisms; others have no known nutritional value and may even be toxic under certain conditions.

Vitamin B4: can refer to the distinct chemicals choline, adenine, or carnitine.[33][34] Choline is synthesized by the human body, but not sufficiently to maintain good health, and is now considered an essential dietary nutrient.[35] Adenine is a nucleobase synthesized by the human body.[36] Carnitine is an essential dietary nutrient for certain worms, but not for humans.[37]

Vitamin B8: adenosine monophosphate (AMP), also known as adenylic acid.[38] Vitamin B8 may also refer to inositol.[39]

Vitamin B10: para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA or PABA), a chemical component of the folate molecule produced by plants and bacteria, and found in many foods.[40][41] It is best known as a UV-blocking sunscreen applied to the skin, and is sometimes taken orally for certain medical conditions.[40][42]

Vitamin B11: pteryl-hepta-glutamic acid (PHGA; chick growth factor). Vitamin Bc-conjugate was also found to be identical to PHGA.[citation needed]

Vitamin B13: orotic acid.[43]

Vitamin B14: cell proliferant, anti-anemia, rat growth factor, and antitumor pterin phosphate named by Earl R. Norris. Isolated from human urine at 0.33ppm (later in blood), but later abandoned by him as further evidence did not confirm this. He also claimed this was not xanthopterin.

Vitamin B15: pangamic acid,[43] also known as pangamate. Promoted in various forms as a dietary supplement and drug; considered unsafe and subject to seizure by the US Food and Drug Administration.[44]

Vitamin B16: dimethylglycine (DMG)[45] is synthesized by the human body from choline.

Vitamin B17: pseudoscientific name for the poisonous compound amygdalin, also known as the equally pseudoscientific name "nitrilosides" despite the fact that it is a single compound. Amygdalin can be found in various plants, but is most commonly extracted from apricot pits and other similar fruit kernels. Amygdalin is hydrolyzed by various intestinal enzymes to form, among other things, hydrogen cyanide, which is toxic to human beings when exposed to a high enough dosage. Some proponents claim that amygdalin is effective in cancer treatment and prevention, despite its toxicity and a severe lack of scientific evidence.[46]

Vitamin B20: L-carnitine.[45]

Vitamin Bf: carnitine.[38]

Vitamin Bm: myo-inositol, also called "mouse antialopaecia factor".[47]

Vitamin Bp: "antiperosis factor", which prevents perosis, a leg disorder, in chicks; can be replaced by choline and manganese salts.[37][38][48]

Vitamin BT: carnitine.[49][37]

Vitamin Bv: a type of B6 other than pyridoxine.

Vitamin BW: a type of biotin other than d-biotin.

Vitamin Bx: an alternative name for both pABA (see vitamin B10) and pantothenic acid.[37][42]

References

^ Fattal-Valevski, A (2011). "Thiamin (vitamin B1)". Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 16 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1177/1533210110392941..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Riboflavin". Alternative Medicine Review. 13 (4): 334–340. 2008. PMID 19152481.

^ Whitney, N; Rolfes, S; Crowe, T; Cameron-Smith D; Walsh, A (2011). Understanding Nutrition. Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

^ National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board, ed. (1998). "Chapter 6 - Niacin". Dietary Reference Intakes for Tjiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

^ University of Bristol (2002). "Pantothenic Acid". Retrieved 16 September 2012.

^ Gropper, S; Smith, J (2009). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

^ University of Bristol (2012). "Biotin". Retrieved 17 September 2012.

^ National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board, ed. (1998). "Chapter 8 - Folate". Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

^ University of Bristol (2002). "Vitamin B12". Retrieved 16 September 2012.

^ DSM (2012). "Vitamin B12". Retrieved 16 September 2012.

^ ab

National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., ed. (1998). "Chapter 4 - Thiamin" (PDF). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 58–86. ISBN 978-0-309-06411-8. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

^ ab National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., ed. (1998). "Chapter 5 - Riboflavin" (PDF). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 87–122. ISBN 978-0-309-06411-8. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

^ ab National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., ed. (1998). "Chapter 6 - Niacin" (PDF). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 123–149. ISBN 978-0-309-06411-8. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

^ "Niaspan" (PDF). www.rxabbott.com.

^ ab

National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., ed. (1998). "Chapter 8 - Folate" (PDF). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 196–305. ISBN 978-0-309-06411-8. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

^ ab

National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., ed. (1998). "Chapter 9 - Vitamin B12" (PDF). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-309-06411-8. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

^ Dupré, A; Albarel, N; Bonafe, JL; Christol, B; Lassere, J (1979). "Vitamin B-12 induced acnes". Cutis; cutaneous medicine for the practitioner. 24 (2): 210–1. PMID 157854.

^ Stipanuk, M.H. (2006). Biochemical, physiological, molecular aspects of human nutrition (2nd ed.). St Louis: Saunders Elsevier p.667

^ Winklera, C; B. Wirleitnera; K. Schroecksnadela; H. Schennachb; D. Fuchs (September 2005). "Beer down-regulates activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro". International Immunopharmacology. 6 (3): 390–395. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2005.09.002. PMID 16428074.

^ Hoyumpa Jr, AM (1980). "Mechanisms of thiamin deficiency in chronic alcoholism". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 33 (12): 2750–2761. doi:10.1093/ajcn/33.12.2750. PMID 6254354. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

^ Leevy, Carroll M. (1982). "Thiamin deficiency and alcoholism". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 378 (Thiamin: Twenty Years of Progress): 316–326. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb31206.x.

^ Pinto, J; Y P Huang; R S Rivlin (May 1987). "Mechanisms underlying the differential effects of ethanol on the bioavailability of riboflavin and flavin adenine dinucleotide". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 79 (5): 1343–1348. doi:10.1172/JCI112960. PMC 424383. PMID 3033022.

^ Spivak, JL; DL Jackson (June 1977). "Pellagra: an analysis of 18 patients and a review of the literature". The Johns Hopkins Medical Journal. 140 (6): 295–309. PMID 864902.

^ Said, HM; A Sharifian; A Bagherzadeh; D Mock (1990). "Chronic ethanol feeding and acute ethanol exposure in vitro: effect on intestinal transport of biotin". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 52 (6): 1083–1086. PMID 2239786. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

^ Halsted, Charles (1990). Picciano, M.F.; Stokstad, E.L.R.; Gregory, J.F., eds. Intestinal absorption of dietary folates (in Folic acid metabolism in health and disease). New York, New York: Wiley-Liss. pp. 23–45. ISBN 978-0-471-56744-8.

^ Watson, Ronald; Watzl, Bernhard, eds. (September 1992). Nutrition and alcohol. CRC Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-8493-7933-8.

^ Craig, Winston J (2009). "Health effects of vegan diets". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5): 1627S–1633S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736N. PMID 19279075.

^ Herbert, Victor (1 September 1998). "Vitamin B-12: Plant sources, requirements, and assay". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 48 (3): 852–8. doi:10.1093/ajcn/48.3.852. PMID 3046314. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

^ abcd Chris Woolston (July 14, 2008). "B vitamins don't boost energy drinks' power". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

^ "Vitamin B injections mentioned".

^ Thornalley, P. J.; Babaei-Jadidi, R.; Al Ali, H.; Rabbani, N.; Antonysunil, A.; Larkin, J.; Ahmed, A.; Rayman, G.; Bodmer, C. W. (2007). "High prevalence of low plasma thiamine concentration in diabetes linked to a marker of vascular disease". Diabetologia. 50 (10): 2164–70. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0771-4. PMC 1998885. PMID 17676306.

^ Shaw, Gary M.; Schaffer, Donna; Velie, Ellen M.; Morland, Kimberly; Harris, John A. (1995). "Periconceptional Vitamin Use, Dietary Folate, and the Occurrence of Neural Tube Defects". Epidemiology. 6 (3): 219–26. doi:10.1097/00001648-199505000-00005. PMID 7619926.

^ Roger L. Lundblad; Fiona Macdonald (30 July 2010). Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (Fourth ed.). CRC Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-4200-0869-2.

^ Zeisel, SH; Da Costa, KA (2009). "Choline: An essential nutrient for public health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (11): 615–23. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x. PMC 2782876. PMID 19906248.

^ Vera Reader (1930). "The assay of vitamin B4" (PDF). Biochem. J. 24 (6): 1827–31. doi:10.1042/bj0241827. PMC 1254803. PMID 16744538.

^ abcd Bender, David A. (29 January 2009). A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. Oxford University Press. p. 521. ISBN 978-0-19-157975-2.

^ abc Berdanier, Carolyn D.; Dwyer, Johanna T.; Feldman, Elaine B. (24 August 2007). Handbook of Nutrition and Food (Second ed.). CRC Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4200-0889-0.

^ "webmd.com VITAMIN B8 (INOSITOL) OVERVIEW INFORMATION".

^ ab "Vitamin B10 (Para–aminobenzoic acid (PABA)): uses, side effects, interactions and warnings". WebMD. WebMD, LLC. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

^ Capozzi, Vittorio; Russo, Pasquale; Dueñas, María Teresa; López, Paloma; Spano, Giuseppe (2012). "Lactic acid bacteria producing B-group vitamins: a great potential for functional cereals products" (PDF). Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 96 (6): 1383–1394. doi:10.1007/s00253-012-4440-2. ISSN 0175-7598. PMID 23093174.

^ ab "Para-aminobenzoic acid". Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

^ ab Herbert, Victor; Subak-Sharpe, Genell J. (15 February 1995). Total Nutrition: The Only Guide You'll Ever Need - From The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. St. Martin's Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-312-11386-5.

^ "CPG Sec. 457.100 Pangamic Acid and Pangamic Acid Products Unsafe for Food and Drug Use". Compliance Policy Guidance Manual. US Food and Drug Administration. March 1995. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

^ ab Velisek, Jan (24 December 2013). The Chemistry of Food. Wiley. p. 398. ISBN 978-1-118-38383-4.

^ Lerner, I. J (1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. PMID 6362828.

^ Velisek, Jan (24 December 2013). The Chemistry of Food. Wiley. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-118-38383-4.

^ Bender, David A. (11 September 2003). Nutritional Biochemistry of the Vitamins. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-139-43773-8.

^ Carter, Herbert E.; Bhattacharyya, P.K.; Weidman, Katharine R.; Fraenkel, G. (1952). "Chemical studies on vitamin BT. Isolation and characterization as carnitine". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 38 (1): 405–416. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(52)90047-7. ISSN 0003-9861.