Old Louisiana State Capitol

Old Louisiana State Capitol

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Old Louisiana State Capitol | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

Old Louisiana State Capitol, 2009 | |

| |

| Location | 100 North Boulevard, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°26′48″N 91°11′21″W / 30.44657°N 91.18903°W / 30.44657; -91.18903 |

| Area | 4.6 acres (1.9 ha) |

| Built | 1847–1852 |

| Architect | Dakin, James H.; Freret, William A. |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference # | 73000862[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 12, 1973 |

| Designated NHL | May 30, 1974[2] |

The Old Louisiana State Capitol, also known as the State House, is a historic government building, and now a museum, at 100 North Boulevard in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S.A.. Built in which housed the Louisiana State Legislature from the mid-19th century until the current capitol tower building was constructed in 1929-32.

It was built to both look like and function like a castle and has led some locals to call it the Louisiana Castle, the Castle of Baton Rouge, the Castle on the River, or the Museum of Political History; although most people just call it the old capitol building. The term "Old State Capitol" in Louisiana is used to refer to the building and not to the two towns that were formerly the capital city: New Orleans and Donaldsonville.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 12, 1973,[1][3][4] and was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 30, 1974.[2]

Contents

1 History

2 Museum of Political History

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

History[edit]

In 1846, the state legislature in New Orleans decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. As in many states, representatives from other parts of Louisiana feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city. In 1840, New Orleans' population was about 102,000, fourth-largest city in the U.S. The 1840 population of Baton Rouge, on the other hand, was only 2,269.

Louisiana's Old State Capitol.

On September 21, 1847, the city of Baton Rouge donated to the state of Louisiana a $20,000 parcel of land for a state capitol building. The land donated by the city for the capitol stands high atop a bluff facing the Mississippi River, a site that some believe was once marked by the red pole, or le baton rouge, which French explorers claimed designated a Native American council meeting site.

New York architect James H. Dakin was hired to design the Baton Rouge capitol building, and rather than mimic the national Capitol Building in Washington, as so many other states had done, he conceived a Neo-Gothic medieval-style castle overlooking the Mississippi.

In 1859, the statehouse was featured and favorably described in De Bow's Review, the most prestigious periodical in the antebellum South. Mark Twain, however, as a steamboat pilot in the 1850s, loathed the sight of it, "It is pathetic ... that a whitewashed castle, with turrets and things ... should ever have been built in this otherwise honorable place."[5]

The statehouse burns on 28 December 1862

In 1862, during the Civil War, Union Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans, and the seat of government retreated from Baton Rouge. The Union's occupying troops first used the capitol building — or "old gray castle," as it was once described — as a prison, and then to garrison African-American troops under General Culver Grover. While used as a garrison the building caught fire twice. This sequence of events transformed Louisiana's capitol into an empty, gutted shell abandoned by the Union Army.

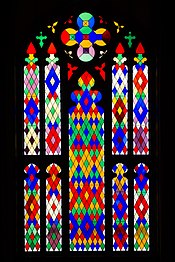

By 1882 the statehouse was totally rebuilt by architect and engineer William A. Freret, who is credited with the installation of the spiral staircase and the stained glass dome, which are the interior focal points. The refurbished statehouse remained in use until 1932, when it was abandoned for the new Louisiana State Capitol building. The Old State Capitol has since been used to house Federally-chartered veterans organizations, and as an office of the Works Progress Administration, among other things.

Museum of Political History[edit]

Stained glass window

Stained glass dome

Stained glass dome, as seen from the ground floor through the spiral staircase

Restored in the 1990s, the Old State Capitol is now the Museum of Political History. Most recently, the exterior façade has been refurbished with shades of tan stucco, in noticeable contrast to its former gray stone coloring. Numerous events are held there including an annual ball wherein the participants re-enact dances and traditions of French culture while wearing 18th- and 19th-century dress.

The museum's location downtown in Baton Rouge is within walking distance of the current capitol tower and of many culturally significant buildings. These include the Old Louisiana Governor's Mansion, the Louisiana Arts and Science Museum, St. Joseph Cathedral, and the widely acclaimed Shaw Center.

In 2010, the Museum of Political History's visitor experience opened, designed by award-winning Bob Rogers and the design firm BRC Imagination Arts, with attractions and exhibits showcasing the building as an architectural treasure and highlighting historic artifacts. Included is an interactive gallery featuring past state governors including infamous Huey P. Long.

A key attraction, The Ghost of the Castle,[6] is a one-of-a-kind multi-dimensional theatrical production, during which visitors come face to face with the ghost of Sarah Morgan Dawson (1842–1909),[7] a young Baton Rouge resident who loved the castle and wrote about it in her book, Sarah Morgan: The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman (originally published in 1913 under a different title). In the roughly 12-minute experience, Sarah's ghost "conjures the building’s remarkable trials and tribulations through history," showing "the determination of everyday Louisianans who have saved the castle time and time again."[8]

Admission to the museum is free, and the building is wheelchair-accessible.

See also[edit]

- National Register of Historic Places listings in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

- National Historic Landmarks in Louisiana

- Old Louisiana Governor's Mansion

References[edit]

^ ab National Park Service (2013-11-02). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Louisiana's Old State Capitol". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2008-06-24. Archived from the original on 2007-12-13.

^ "Louisiana State Capitol (1849-62; 1882-1932)" (PDF). State of Louisiana's Division of Historic Preservation. Retrieved May 11, 2018. with six photos and two maps

^ Ruth S. LeCompte (November 15, 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form: Old Louisiana State Capitol". National Park Service. Retrieved May 11, 2018. With nine photos.

^ Life on the Mississippi, Chapter 40.

^ The Ghost of the Castle (2010) at IMDb, retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ Sarah Morgan Dawson at Find a Grave, retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ Storyline of presentation at IMDb, crediting Old State Capitol; retrieved 31 May 2017.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old Louisiana State Capitol. |

Louisiana's Old State Capitol and Museum of Political History - official website- Louisiana's Old State Capitol Foundation

- Governor Henry Watkins Allen Memorial by La-Cemeteries

- Library of Congress, Survey number HABS LA-1132

- BatonRougeGuide.com

Baton Rouge Digital Archive from the East Baton Rouge Parish Library

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document "[1]".

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document "[1]".

Categories:

- Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Louisiana

- National Historic Landmarks in Louisiana

- Buildings and structures in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Former state capitols in the United States

- Museums in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- History museums in Louisiana

- Tourist attractions in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Works Progress Administration in Louisiana

- National Register of Historic Places in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.528","walltime":"0.673","ppvisitednodes":{"value":2983,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":87499,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":5108,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":19,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":4,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":14191,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":1,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 549.771 1 -total"," 60.96% 335.157 2 Template:Infobox"," 54.87% 301.686 1 Template:Infobox_NRHP"," 21.72% 119.414 1 Template:Reflist"," 18.57% 102.093 4 Template:Cite_web"," 15.26% 83.913 1 Template:NRISref"," 14.65% 80.565 1 Template:Country_abbreviation"," 11.93% 65.607 1 Template:Commons_category"," 10.02% 55.091 1 Template:Commons"," 9.59% 52.744 1 Template:Sister_project"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.255","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":7418973,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1267","timestamp":"20190119113554","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});});{"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"Old Louisiana State Capitol","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Louisiana_State_Capitol","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q7084390","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q7084390","author":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png"}},"datePublished":"2007-02-24T08:21:57Z","dateModified":"2018-12-06T21:16:09Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/34/OldLAStateCapitol01.JPG"}(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":768,"wgHostname":"mw1267"});});