Erlangen

Erlangen | |

|---|---|

View over Erlangen, 2012 | |

Coat of arms | |

Location of Erlangen | |

Erlangen Show map of Germany  Erlangen Show map of Bavaria | |

| Coordinates: 49°35′N 11°1′E / 49.583°N 11.017°E / 49.583; 11.017Coordinates: 49°35′N 11°1′E / 49.583°N 11.017°E / 49.583; 11.017 | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Middle Franconia |

| District | independent city |

| Subdivisions | 9 city districts |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Florian Janik (SPD) |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 76.96 km2 (29.71 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 279 m (915 ft) |

| Population (2017-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 110,998 |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 91052, 91054, 91056, 91058 |

| Dialling codes | 09131, 0911 (district Hüttendorf), 09132 (district Neuses), 09135 (district Dechsendorf) |

| Vehicle registration | ER |

| Website | www.erlangen.de |

Erlangen (German pronunciation: [ˌɛɐ̯ˈlaŋən] (![]() listen); East Franconian: Erlang) is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative district Erlangen) and with 113,752 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2018) it is the smallest of the eight major cities in Bavaria.[3] The number of inhabitants exceeded the limit of 100,000 in 1974, making Erlangen a major city.

listen); East Franconian: Erlang) is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative district Erlangen) and with 113,752 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2018) it is the smallest of the eight major cities in Bavaria.[3] The number of inhabitants exceeded the limit of 100,000 in 1974, making Erlangen a major city.

Together with Nuremberg, Fürth and Schwabach, Erlangen forms one of the three metropolises in Bavaria. Together with the surrounding area, these cities form the European Metropolitan Region of Nuremberg, one of 11 metropolitan areas in Germany. Together with the cities of Nuremberg and Fürth, Erlangen also forms a triangle of cities, which represents the heartland of the Nuremberg conurbation.

An element of the city that goes back a long way in history, but is still noticeable, is the settlement of Huguenots after the withdrawal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Today, the city is dominated by the Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and the Siemens technology group.

Contents

1 Geography

1.1 Neighboring municipalities

1.2 City arrangement

1.2.1 Districts and statistical districts

1.2.2 Gemarkungen

1.2.3 Historical city districts

1.3 Climate

2 History

2.1 Overall history

2.1.1 Early history

2.1.2 From Villa Erlangen to the Thirty Years War

2.1.3 Foundation of the new town

2.1.4 Erlangen in the Kingdom of Bavaria

2.1.5 Weimar Republic

2.1.6 During Nazism

2.1.7 After the Second World War

2.2 History of the Erlangen Garrison

2.3 History of the Erlangen University

2.4 Incorporations into the municipal area

2.5 Historical population

3 Points of interest

4 Bergkirchweih

5 Mayors of Erlangen

6 International relations

6.1 Further partnerships

7 Environmental protection

7.1 Traffic

7.2 Nature and landscape conservation

8 Notable residents

9 References

10 External links

Geography

Erlangen is located on the edge of the Middle Franconian Basin[4] and at the floodplain of the Regnitz river.[5] The river divides the city into two halfs of approximately equal sizes. In the western part of the city the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal lies parallel to the Regnitz.

Neighboring municipalities

The following municipalities or non-municipal areas are adjacent to the city of Erlangen. They are listed clockwise, starting in the north:

The unincorporated area Mark, the municipalities Möhrendorf, Bubenreuth, Marloffstein, Spardorf and Buckenhof and the forest area Buckenhofer Forst (all belonging to the district of Erlangen-Höchstadt), the independent cities of Nuremberg and Fürth, the municipality Obermichelbach (district of Fürth), the city of Herzogenaurach and the municipality Hessdorf (both in the district of Erlangen-Höchstadt).

City arrangement

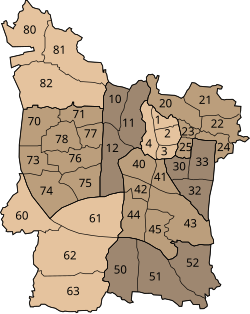

Districts and statistical districts of Erlangen

Gemarkungen of Erlangen

Erlangen officially consists of nine districts and 40 statistical districts, 39 of which are inhabited.[6] In addition, the urban area is subdivided into twelve land registry and land law relevant districts whose boundaries deviate largely from those of the statistical districts. The districts and statistical districts are partly formerly independent municipalities,[7][8] but also include newer settlements which names have also been coined as district names. The traditional and subjectively perceived boundaries of neighborhoods often deviate from the official ones.

Districts and statistical districts

|

|

|

Gemarkungen

Erlangen is divided into the following Gemarkungen:

|

|

|

Historical city districts

Some still common names of historical districts were not taken into account with the official designations. Examples are:

- Brucker Werksiedlung (in Gemarkung Bruck)

- Erba-Siedlung (in Gemarkung Bruck, am Anger)

- Essenbach (near Burgberg, north of Schwabach)

- Heusteg (in Gemarkung Großdechsendorf)

- Königsmühle (in Gemarkung Eltersdorf)

- Paprika-Siedlung (in Gemarkung Frauenaurach)

- Schallershof (in Gemarkung Frauenaurach)

- Siedlung Sonnenblick (in Gemarkung Büchenbach)

- Stadtrandsiedlung (in Gemarkung Büchenbach)

- St. Johann (in the statistical district Alterlangen)

- Werker (near Burgberg, east of the Regnitz)

- Zollhaus (eastern city center)

Climate

Erlangen is located in a transition zone from maritime to continental climate: the city is relatively low in precipitation (650mm per year), as usual in continental climate, but relatively warm with an annual mean temperature of 8.5 °C. The castle mountain in particular protects the area of the core city from cold polar air. In contrast, the Regnitzgrund is the cause of frequent fog.[9]

History

Overall history

Early history

The Kosbacher Altar

In the prehistory of Bavaria, the Regnitz valley already played an important role as a passageway from north to south. In Spardorf a blade scraper was found in loess deposits, which could be attributed to the Gravettians, which places it at an age of about 25,000 years.[10] Due to the relatively barren soils in the area farming and settlements could only be detected at the end of the Neolithic (2800-2200 BC).[10] The "Erlanger Zeichensteine" (Erlangen Sign Stones, sandstone plates with petroglyphs) in the Mark-Forst north of the city also originated in this time period.[11] The stone plates were later resused as grave borders in the Urnfield period (1200–800 BC).[12]

Once investigated in 1913, it was found that the burial mound in Kosbach contained finds from the urnfield time as well as from the Hallstatt and La Tène period.[13] Next to the hill, the so-called "Kosbacher Altar", which was originated in the late Hallstatt period (about 500 BC),[14] was constructed. The altar is unique in this form and consists of a square stone setting with four upright, figural pillars at the corners and one under the center. The reconstruction of the site can be visited in the area, the middle guard is exhibited in the Erlangen city museum.[15][16]

From Villa Erlangen to the Thirty Years War

Certificate of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II. from 1002, first mentioning Erlangen

Erlangen is first mentioned by name in a document from 1002. The origin of the name Erlangen is not clear. Attempts of local research to derive the name of alder (tree species) and anger (meadow ground), do not meet toponymical standards.[17]

As early as 976, Emperor Otto II had donated the church of St. Martin in Forchheim with accessories to the diocese of Würzburg.[18] Emperor Henry II confirmed this donation in 1002 and authorized its transfer from the bishopric to the newly founded Haug Abbey.[19] In contrast to the certificate of Otto II, the accessories, which also included the "villa erlangon" located in Radenzgau, were described in more detail here. At that time the Bavarian Nordgau extended to the Regnitz in the west and to the Schwabach in the north. Villa Erlangon must therefore have been located outside of these borders and thus not in the area of today's Erlangen Altstadt. However, as the name Erlangen is unique to today's town in Germany, the certificate could have only referred to it. The document also provides an additional piece of evidence: In 1002, Henry II bestowed further areas west of the Regnitz, including one mile from the Schwabach estuary to the east, one mile from this mouth upstream and downstream. These two squares are described in the document only by their lengths and the two river names. No reference to a specific place is given. They are also unrelated to the accessories of St. Martin, which included the villa erlangon, another reason why it must have been physically separated from the area of the two miles. Size and extent of the two squares correspong approximately to the area requirement of a village at the time, which supports the assumption that at the time of certification a settlement was under construction, which should be legitimized by this donation and later, as in similar cases, has adopted th name of the original settlement.[17] The new settlement was built in a triangle, today bordered by the streets Hauptstraße, Schulstraßeand Lazarettstraße, on a flooding-free sand dune.

Only 15 years later, in 1017, Henry II confirmed an exchange agreement, through which St. Martin and its accessories (including Erlangen) were given to the newly founded Bishopric of Bamberg, where it remained until 1361. During these centuries, the place name appears only sporadically.[20]

On 20 August 1063, Emperor Henry IV created two documents "actum Erlangen" while on a campaign. Local researchers therefore concluded that Erlangen must have already gained so much in extent that in 1063, Henry IV took his residence there with many princes and bishops[21] and was therefore the seat of a King's Court. It was even believed that this court could have been located in the Bayreuther Straße 8 and given away without mention by the certificate of 1002. Other evidence of this estate is also missing.[17] It is regarded as most likely today, that Henry IV was not residing in the "new" Erlangen, but rather in the older villa erlangon, as the north-south valley road changed to the left river bank of the Regnitz and then ran in the direction of Alterlangen, Kleinseebach-Baiersdorf to the north, to avoid the heights of the Erlangen Burgberg.[22]

Otherwise, Erlangen was usually only mentioned if the bishop pledged it due to lack of money. How exactly the village developed is unknown. Only the designation "grozzenerlang" in a bishop's urbarium from 1348 may be an indication that the episcopal village had outstripped the original villa erlangon.[22]

In December 1361, Emperor Charles IV bought "the village Erlangen including all rights, benefits and belongings".[21] and incorporated it into the area designated as New Bohemia, which was a fief of the Kingdom of Bohemia. Under the crown of Bohemia, the village developed rapidly. In 1367 the emperor spent three days in Erlangen and gave the "citizen and people of Erlangen" grazing rights in the imperial forest.[17] In 1374, Charles IV granted the inhabitants of Erlangen seven years of tax exemption. The money should instead be used to "improve" the village.[17] At the same time he lent the market right to Erlangen. Probably soon after 1361, the new ruler of the administration of the acquired property west of the town built the Veste Erlangen, on which a bailiff resided. King Wenceslaus built a mint and officially granted township to Erlangen in 1398. He also gave the usual town privileges: Collection of tolls, construction of a department store with bread and meat bank and the construction of a defensive wall.[21]

Ruins of the Veste Erlangen, around 1730

Two years later, in 1400, the prince-electors unelected. He sold his Frankish possessions, including Erlangen, to his brother-in-law, the Nuremberg burgrave Johann III due to lack of funds in 1402. During the process of division of the burggrave property in Franconia, Erlangen was added to the Upper Principality, the future Principality of Bayreuth. The Erlangen coining facility ceased its operation because the Münzmeister was executed for counterfeiting in Nuremberg.[23]

During the Hussite Wars the town was completely destroyed for the first time in 1431.[17] The declaration of war by Margrave Albrecht Achilles to the city of Nuremberg in 1449 lead to the First Margrave War. However, as the army of Albrecht could not completely enclose the city, Nuremberg troops broke out again and devastated the Margravial towns and villages. As reported by a Nuremberg chronicler, they "burnt the market at most in Erlangen and brought a huge robbery". As soon as the town had recovered, Louis IX, Duke of Bavaria attacked the Margrave in 1459. Erlangen was raided and plundered again, this time by Bavarian troops. In the following years the town recovered again. Erlangen was spared from the Peasants' War in 1525 and the introduction of the Reformation in 1528 was peaceful. However, when Margrave Albert Alcibiades triggered the Second Margrave War, Erlangen was attacked again by the Nurembergers and partially destroyed. It was even considered to completely abandon the town. Because Emperor Charles V imposed the imperial ban on Albrecht, the Nurembergers incorporated Erlangen into their own territory. Albrecht died in January 1557. His successor, George Frederick, requested that the imperial sequestation over the Principality of Kulmbach be reversed and was able to take back the government one month later. Under his rule, the town recovered from the war damage and remained unharmed until well into the Thirty Years' War.[23]

Little is known about the place itself and about the people who lived here during this period.

From 1129, members of the noble family "von Erlangen" appear as witnesses in notarizations. They were probably ministers of the von Gründlach family. The family had numerous possessions in and around Erlangen as antecedents of the von Gründlach imperial fiefdom. Despite multiple mentions in documents, it is no longer possible to establish a line of ancestry. At the beginning of the 15th century the family died out.[24]

In a foundation deed of 1328 a property is mentioned on which "heinrich the old sits". Twenty years later, in the Episcopal Urbar of 1348 (see above), seven landowners who were obliged to pay interest were named. For the first time, the entire city is recorded in the register of the Common Penny of 1497: 92 households with 212 adults (over 15 years). If one assumes 1.5 children under the age of 15 per household, the population is calculated to be around 350.[25] This figure is unlikely to have changed much in the subsequent period. The Urbar of 1528 lists 83 taxable house owners[25] and the Türkensteuerliste of 1567 97 heads of households, plus five children under guardianship.[23] A complete list of all households, including tenants, arranged by street, was drawn up in 1616 by the Old Town priest Hans Heilig: At the beginning of the Thirty Years' War, the city counted 118 households with about 500 persons.[26]

The old town of Erlangen has been completely destroyed several times, most recently in the great fire of 1706. Only parts of the city wall date back to the late Middle Ages. After the fire of 1706, the cityscape with its street layout had to be rigorously adapted to the regular street scheme of the newly built "Christian-Erlang", which had its own administration (judicial and chamber college)[27] until the administrative reform of 1797. Only the streets Schulstraße, Lazarettstraße and Adlerstraße were spared. The low cellars, however, survived all destruction and fires mostly unscathed. Above them, the buildings were newly erected. For this reason, two Erlangen architects have been surveying the cellars of the old town on behalf of the Heimat- und Geschichtsverein since 1988.[28] At the same time, the city archaeology of Erlangen has excavated in the courtyard of the Stadtmuseum.[29] Both measures give an approximate picture of the late medieval or early modern location: Pfarrstraße ran further north, northern Hauptstraße somewhat further east than today. The western houses at Martin-Luther-Platz protruded to different extents into today's area; on its eastern side the buildings ran diagonally from today's Neue Straße to the city gate "Oberes Tor" (between Hauptstraße 90 and 91). The eastern city wall first led south from Lazarettstraße, then turned slightly southwest from Vierzigmannstraße and cut the base of today's Old Town Church at the northeast corner of the nave. Foundations of this wall, which run exactly in the described direction, were discovered during the excavations in the courtyard of the town museum. Outside the upper gate the upper suburb began to develop. In front of the city gate "Bayreuther Tor" was the lower suburb (Bayreuther Straße to Essenbacher Straße) with the mill at the Schwabach. The Veste was located in the west of the city.

Foundation of the new town

After the Thirty Years' War, the town was rebuilt relatively quickly. On 2 December 1655 the parish church was consecrated to the title of Holy Trinity. The situation changed in 1685 when French king Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had granted Calvinist subjects - called Huguenots by their opponents - religious freedom since 1598. The revocation triggered a wave of refugees of about 180,000 Huguenots who settled mainly in the Dutch Republic, the British Isles, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and some German principalities. A small number of religious refugees later went to Russia and the Dutch and British colonies.

Margrave Christian Ernst also took advantage of this situation and offered the refugees the right to settle in his principality, which was still suffering from the consequences of the Thirty Years' War, in order to promote its economy in the sense of mercantilism through the settlement of modern trades. He was thus one of the first Lutheran princes in Germany to accept Calvinists into his country and even to guarantee them the freedom to practise their religion. The first six Huguenots reached Erlangen on 17 May 1686, about 1500 followed in several waves. In addition, several hundred Waldensians came, however, as they were unable to settle down they moved on in 1688. Even before it was foreseeable how many refugees could be expected, the margrave decided to found the new town of Erlangen as a legally independent settlement south of the small town called Altstadt Erlangen. The rational motive of promoting the economy of one's own country was associated with the hope of wealth as a city founder, which was typical of absolutism.

The oldest preserved design of the Erlangen Neustadt, red washed pen drawing (1686), attributed to Johann Moritz Richter

The new city was conveniently located on one of the most important trade and travel routes to and from Nuremberg. Water was to be drained from the nearby Regnitz for a canal necessary for certain trades, however this failed due to the sandy ground. The plan of the city, which at first sight appeared simple, but was in fact extremely differentiated and highly sophisticated, was designed by the margravial master builder Johann Moritz Richter using the "golden ratio" and ideal criteria. The rectangular layout is characterised by the main street, which is designed as an axis of symmetry and has two unequal squares, and the "Grande Rue", which surrounds the inner core and whose closed corners, designed as right angles, act like hinges, giving the entire layout strength and unity. As the plan made clear, it was not the design of the individual buildings that was important, but the overall uniformity of the entire city. Even today, the historical core is characterised by this uniform, relatively unadorned facades of the two-storey and three-storey houses in straight rows with the eaves side facing the street. The construction of the town began on 14 July 1686 with the laying of the foundation stone of the Huguenot Church. In the first year about 50 of the planned 200 houses were completed. The influx of the Huguenots did not meet expectations, because their refugee mentality did not change into an immigrant mentality until 1715. The change of mentality happened in this year, as the peace treaties after the War of the Spanish Succession ruled out their return to France, but also because the Margrave was engaged as commander in the War of the Palatinate Succession against France from 1688 to 1697. Therefore, further expansion stagnated. It was not until 1700 that he received new impetus from the construction of the margravial palace and the development of Erlangen into a royal seat and one of the six provincial capitals.[30] After a major fire destroyed almost the entire old part of the town of Erlangen on 14 August 1706, it was rebuilt on the model of the new town with straightened street and square fronts and a two-storey, somewhat more individually designed house type. In Erlangen, this resulted in the special case of two neighbouring planned cities, which is probably unique in the history of European ideal cities. The old city of Erlangen, which was actually older and still managed independently until 1812, is younger in terms of architectural history than the new city of Erlangen.[31]

The ground plan of 1721 shows the integration of Erlangen Neustadt and the reconstructed old town into the baroque overall concept. Coloured copper engraving (1721) by Johann Christoph Homann, published by Johann Baptist Homann

The new town, named after its founder Christian-Erlang in 1701, became not only the destination of the Huguenots, but also of Lutherans and German Reformed, who had been granted the same privileges as the Huguenots. In 1698, approximately 1000 Huguenots and 317 Germans lived in Erlangen. Due to immigration, however, the Huguenots soon became a French-speaking minority in a German city. The French influence diminished further in the following years. In 1822, the last service in French was held in the Huguenot Church.

Erlangen in the Kingdom of Bavaria

In 1792 Erlangen and the Principality of Bayreuth became part of the Kingdom of Prussia. As Napoleon won the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt, the two principalities were brought under French rule as a province. In 1810 the principality of Bayreuth was sold to the allied kingdom of Bavaria for 15 million francs.[32] In 1812 the old town and the new town - until then still called Christian-Erlang - were united to form one town, which received the name Erlangen. In the period that followed, the city and its infrastructure were rapidly expanded. Especially the opening of the Ludwig Canal and the railway connections as well as the garrison and the university gave important impulses for the urban development.

Already with the Bavarian community reform of 1818, the city received its own administration, which was later called "free of district". In 1862 the district office Erlangen was formed, from which the administrative district Erlangen emerged.

Weimar Republic

After their defeat in the First World War, the antidemocratic parties NSDAP, DNVP and KPD also gained strong popularity in Erlangen due to high inflation, reparations payments and the world economic crisis. A two-tier society was established, which was reinforced by industrial settlements. In the city council, state parliament and Reichstag elections, the SPD initially held a relatively stable majority of 40%. On the other hand there were the parties of the centre and the right, whose supporters came from the middle class, the university and the civil service. The NSDAP was represented in the city council from 1924. Five years later, the Erlangen university became the first German university with its student representation controlled by the party, making it a centre of nationalist and anti-democratic sentiment. Many students and professors became intellectual pioneers of National Socialism. From 1930 onwards, the political situation escalated, fuelled by mass unemployment caused by the Great Depression. Both left and right unions organised marches and caused street fights. Despite the strong influx in popularity of the NSDAP, the SPD won 34% of the votes in the 1933 Reichstag election (average: 18.3%)[33].

During Nazism

Stolpersteine with the names of murdered Erlangen Jews in front of the building Hauptstraße 63

A plaque on the Schlossplatz commemorates the Nazi book burnings

After the seizure of power by the NSDAP, boycotts of Jewish shops, the desecration and destruction of the monument dedicated to the Jewish professor and Erlangen honorary citizen Jakob Herz on Hugenottenplatz and the burning of books also took place in Erlangen. The NSDAP-controlled city council made Chancellor Hitler, President von Hindenburg and Gauleiter Streicher honorary citizens, the main street was renamed Adolf-Hitler-Straße ("Adolf-Hitler-Street"). During the Reichspogromnacht the Jewish families from Erlangen (between 42 and 48 persons), Baiersdorf (three persons) and Forth (seven persons) were rounded up and humiliated in the courtyard of the former town hall (Palais Stutterheim), their flats and shops partly destroyed and plundered, then the women and children were taken to the Wöhrmühle (an island in the Regnitz river in Erlangen), the men to the district court prison and then to Nuremberg to prison. Those who could not leave Germany in the following wave of emigration were deported to concentration camps, where most died. In 1944 the city was declared "free of Jews", although a "Half-Jew " stayed in town until the end of the war, protected by the police chief.[34]

As the academic community supported NS politics to a large extent, there was no active resistance from the university. In the sanatorium and nursing home (today part of the Clinic am Europakanal), forced sterilisations and selections of patients for the National Socialist "euthanasia murders (Aktion T4)" took place.

From 1940, prisoners of war and forced labourers were deployed in the Erlangen armament factories. In 1944 they already accounted for 10% of the population of Erlangen. Their accommodation in barrack camps and treatment were inhuman.

In 1983, Erlangen was one of the first cities in Bavaria to begin to reappraise its National Socialist history in an exhibition at the city's museum.[35] In the same year, Adolf Hitler and Julius Streicher were officially deprived of their honorary citizenship, which had automatically expired with their death, as a symbolic gesture of distance.

After the Second World War

During the Second World War, 4.8% of Erlangen was destroyed by bombings; 445 flats were completely destroyed.[36] When the superior American troops moved in on 16 April 1945, the local commander of the German troops, Lieutenant Werner Lorleberg handed over the city without a fight, thus avoided a battle inside the city area that would have been pointless and costly. Lorleberg himself, who until the end was regarded as a supporter of the National Socialist regime, died at Thalermühle on the same day. Whether he was shot by German soldiers when he tried to persuade a scattered task force to give up, or whether he committed suicide there after the surrender message was delivered, is not conclusively clarified. Lorlebergplatz in Erlangen, named after him, reminds us of him. The note about Lorleberg, which is attached to the place, refers to his death, which had saved Erlangen from destruction.

Picture postcard of the Nuremberg Gate

After the handover of the city, American tanks severely damaged the last preserved city gate (the Nuremberg Gate built in 1717), which was blown up shortly afterwards. This probably also happened at the instigation of shopkeepers living in the main street who, like the passing American troops, found the baroque gate an obstacle to traffic because of its relatively narrow passage. The other city gates had already been demolished in the 19th century.

During the district and area reform in 1972, the district of Erlangen was united with the district of Höchstadt an der Aisch. Erlangen itself remained an independent town and became the seat of the new administrative district. Through the integration of surrounding communities, the city was considerably enlarged, so that in 1974 it exceeded the 100,000-inhabitant limit and thus became a major city of Germany. In 2002 Erlangen celebrated its thousandth anniversary.

On 25 May 2009, the city was awarded the title of "Place of Diversity" by the Federal Government in the context of an initiative launched in 2007 by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, the Federal Ministry of the Interior and the Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration to strengthen the commitment of municipalities to cultural diversity. Erlangen was awarded the title "Federal Capital for Nature and Environmental Protection" in 1990 and 1991 for its highly successful policy of creating a balance between economy and ecology. It was the first German prizewinner and the first regional authority to be included in the list of honour of the United Nations Environment Agency in 1990. Due to the above-average proportion of medical and medical-technical facilities and companies in relation to the number of inhabitants, Lord Mayor Siegfried Balleis developed the vision of developing Erlangen into the "Federal Capital of Medical Research, Production and Services" by 2010 when he took office in 1996.[37]

History of the Erlangen Garrison

Until the 18th century, the margrave's soldiers were quartered with private individuals during missions in the Erlangen area. After the city was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1810, it made several attempts to set up a garrison, mainly for economic reasons, but without success at first. When in 1868 the general compulsory military service was introduced with the option to do military service and study at the same time, the garrison became a vital location factor for the city and especially for the university. A renewed application was successful, so that on 12 March 1868 the 6th Hunter Battalion moved into Erlangen. The Bavarian Army was housed in various municipal buildings and used, among other things, today's Theaterplatz square for its exercises. In addition, a shooting range was set up in the Meilwald forest.

The hunter monument in the Hindenburgstraße reminds of the 6th hunter battalion.

In 1877 the first hunting barracks were completed in the Bismarckstraße (name of street in Erlangen). One year later the hunter battalion was replaced by the III Battalion of the Royal Bavarian 5th Infantry Regiment Grand Duke of Hesse. In 1890 the entire 19th Infantry Regiment was stationed, which resulted in the construction of the Infantry Barracks and the drill ground. In 1893 a "Barrack Casernement" was established in the north-west corner of the drill ground and used as a garrison hospital from 1897. On 1 October 1901, the 10th Field Artillery Regiment moved into the town, for which the artillery barracks were erected. At that time the city had about 24,600 inhabitants, 1160 students and now a total of 2200 soldiers, whom the population held in high esteem, especially after the military successes against France in 1870/71.

In World War I, both Erlangen regiments, which were subordinated to the 5th Royal Bavarian Division, fought exclusively on the Western Front. Over 3,000 soldiers lost their lives. After the war Erlangen retained its status as a garrison town. Since the Treaty of Versailles stipulated a reduction of the army to 100,000 soldiers, only the training battalion of the 21st (Bavarian) Infantry Regiment of the newly founded Reichswehr remained in the city.

During the time of National Socialism, the reintroduction of compulsory military service in 1935 and the German re-armament also led to a massive expansion of the military installations in Erlangen. The Rhineland barracks, in which various infantry units were stationed one after the other, the tank barracks, in which the Panzer Regiment 25 was stationed from October 1937, a catering office, an ammunition and equipment depot and a training area were built in the Reichswald forest near Tennenlohe.

The invasion of troops by the 7th US Army on 16 April 1945 meant not only the end of World War II for Erlangen, but also the end as a location for German troops. Instead, US American units moved into the military facilities, which had remained undestroyed, and have even been considerably expanded since the reactivation of the 7th US Army in 1950/51: The area of the now Ferris Barracks (named after Lt. Geoffrey Ferris, who died in Tunisia in 1943) was extended to 128 hectares, the living area for the soldiers and their relatives to 8.5 hectares and the training area in Tennenlohe to 3240 hectares. On average, 2500 soldiers and 1500 relatives were stationed in Erlangen in the 1980s.

The population of Erlangen met the presence of the Americans with mixed feelings. Although their protective function during the Cold War and the jobs associated with stationing were welcomed, the frequent conflicts between the soldiers and the civilian population and numerous manoeuvres were a constant source of offence. The first open protests took place during the Vietnam War. These were directed against the training area and the shooting range in Tennenlohe, where even nuclear weapons were suspected, as well as against the ammunition bunkers in the Reichswald. Helmut Horneber, who had been responsible for the American training area for many years as forest director, pointed out in 1993 how exemplarily the American troops had protected the forest areas.[38]

Due to the numerous problems, there were already considerations in the mid-1980s to relocate the garrison from the urban area. After the opening of the Inner German border in 1989, there were growing signs of an imminent withdrawal. In 1990/91 the troops stationed in Erlangen (as part of the VII US Corps) were detached for deployment in the Gulf War. After the end of the Gulf War, the dissolution of the site began and was completed in July 1993. On 28 June 1994, the properties were officially handed over to the German federal government. This marked the end of Erlangen's 126-year history as a garrison town.[39]

History of the Erlangen University

The founder of the university, Margrave Friedrich

The second decisive event for the development of Erlangen was the foundation of the university, in addition to the foundation of the Neustadt. Plans already existed during the Reformation, but it was not until 1742 that Margrave Frederick of Brandenburg-Bayreuth donated a university for the residence city of Bayreuth, which was moved to Erlangen in 1743. The institution, which was equipped with modest means, wasn't met with much approval at first. Only when Margrave Charles Alexander of Brandenburg-Ansbach put it on a broader economic footing did the number of students slowly increase. Nevertheless, it remained below 200 and dropped to about 80 when the margraviate was incorporated into the kingdom of Bavaria. The threatened closure was only averted because Erlangen had the only Lutheran theological faculty in the kingdom.[40]

Like the other German universities, the boom came at the beginning of the 1880s. The number of students rose from 374 at the end of the winter semester 1869/70 to 1000 in 1890.[41] While in the early years law students were at the forefront, at the beginning of the Bavarian period the Faculty of Theology was the most popular. It was not until 1890 that the Faculty of Medicine overtook it. The number of full professors rose from 20 in 1796 to 42 in 1900, almost half of whom were employed by the Faculty of Philosophy, which also included the natural sciences. These did not form their own faculty until 1928. Today there are almost 39,000 students, 312 chairs and 293 professorships in five faculties (as of winter semester 2018/19).[42] At the beginning of the 2011/12 winter semester, Erlangen University was one of the twelve largest universities in Germany for the first time.

In 1897 the first women were allowed to study, the first doctorate was awarded to a woman in 1904.[43] After its founder, Margrave Friedrich, and its patron, Margrave Alexander, the university was named Friedrich-Alexander University.

Incorporations into the municipal area

Formerly independent communities and districts that were incorporated into the city of Erlangen:

- 1 May 1919: Sieglitzhof (municipality of Spardorf)[44]

- 1 April 1920: Alterlangen (community of Kosbach)[44]

- 1 August 1923: Büchenbach[44] and hamlet of Neumühle

- 15 September 1924: Bruck[44]

- 1960: Parts of Eltersdorf

- 1 January 1967: Kosbach, Häusling and Steudach[45]

- 1 July 1972: Eltersdorf, Frauenaurach, Großdechsendorf, Hüttendorf, Kriegenbrunn, Tennenlohe[45]

- 1 July 1977: Königsmühle (City of Fürth)[46]

Above all, the incorporation during the municipal reform in 1972 contributed significantly to the fact that Erlangen exceeded the 100,000-inhabitant limit in 1974 and thus officially became a city.[44]

Historical population

Largest groups of foreign residents[47] | |

| Nationality | Population (31.12.2018) |

|---|---|

| 1,800 | |

| 1,692 | |

| 1,324 | |

| 1,251 | |

| 1,209 | |

| 1,056 | |

| 778 | |

| 771 | |

| 676 | |

| 625 | |

In the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times, only a few hundred people lived in Erlangen. Due to numerous wars, epidemics and famines, the increase in population was very slow. In 1634, as a result of the destruction in the Thirty Years' War, the town was completely deserted. In 1655, the population reached 500 again, therefore reaching pre war levels. On 8 March 1708 Erlangen was declared the sixth state capital.[48] By 1760, the population had risen to over 8000. Due to the famines 1770–1772, the population declined to 7224 in 1774. After an increase to approximately 10,000 people in 1800, the population of Erlangen fell once again as a result of the Napoleonic wars and reached 8592 in 1812.

During the 19th century, this number doubled to 17,559 in 1890. Due to numerous incorporations, the population of the city rose to 30,000 by 1925 and again in the following decades, reaching 60,000 in 1956. Because of district and areal reforms in 1972, the population of the city exceeded the limit of 100,000 in 1974, making Erlangen a major city.[49]

Increased demand for urban homes has led the population to grow further in the 2000s, with predictions claiming the city would reach over 115,000 residents in the 2030s within the current urban area.[50]

|

|

|

|

|

Points of interest

Erlangen palace

- The University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität) was founded in 1742 by Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, in the city of Bayreuth, but was relocated to Erlangen the next year. Today, it features five faculties; some departments (Economics and Education) are located in Nuremberg. About 39,000 students study at this university, of which about 20,000 are located in Erlangen.

- The Botanischer Garten Erlangen is a botanical garden maintained by the university.

Bergkirchweih

The Bergkirchweih is an annual beer festival, similar to the Oktoberfest in Munich but smaller in scale. It takes place during the twelve days before and after Pentecost (that is, 49 days after Easter); this period is called the "fifth season" by the locals. The beer is served at wooden tables in one-litre stoneware jugs under the trees of the "Berg", a small, craggy, and wooded hill with old caves (beer cellars) owned by local breweries. The cellars extend for 21 km (14 miles)[51] throughout the hill (the "Berg") and maintain a constant cool underground temperature. Until Carl von Linde invented the electric refrigerator in 1871, this was considered to be the largest refrigerator in Southern Germany.[52]

The beer festival draws more than one million visitors annually. It features carnival rides of high tech quality, food stalls of most Franconian dishes, including bratwurst, suckling pig, roasted almonds, and giant pretzels.

It is commonly known by local residents as the "Berchkärwa" (pronounced "bairch'-care-va") or simply the "Berch", like in "Gehma auf'n Berch!" ("Let's go up the mountain!").

This is an outdoor event frequented and enjoyed by Franconians. Despite a relatively high number of visitors, it is not commonly known by tourists, or people living outside Bavaria.

Mayors of Erlangen

- 1818–1827: Johann Sigmund Lindner

- 1828–1855: Johann Wolfgang Ferdinand Lammers

- 1855–1865: Carl Wolfgang Knoch

- 1866–1872: Heinrich August Papellier

- 1872–1877: Johann Edmund Reichold

- 1878–1880: Friedrich Scharf

- 1881–1892: Georg Ritter von Schuh

- 1892–1929: Theodor Klippel

- 1929–1934: Hans Flierl

- 1934–1944: Alfred Groß (NSDAP)

- 1944–1945: Herbert Ohly (NSDAP)

- 1945–1946: Anton Hammerbacher (SPD)

- 1946–1959: Michael Poeschke (SPD)

- 1959–1972: Heinrich Lades (CSU)

- 1972–1996: Dietmar Hahlweg (SPD)

- 1996–2014: Siegfried Balleis (CSU)

- 2014–present: Florian Janik (SPD)

International relations

Erlangen is twinned with several cities:

Eskilstuna, Sweden, since 1961.[53]

Eskilstuna, Sweden, since 1961.[53]

Rennes, France, since 1964.[54]

Rennes, France, since 1964.[54]

Vladimir, Russia, since 1983.[55]

Vladimir, Russia, since 1983.[55]

Jena, Thuringia, Germany, since 1987.[56]

Jena, Thuringia, Germany, since 1987.[56]

Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom, since 1989.[57]

Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom, since 1989.[57]

San Carlos, Nicaragua, since 1989.[58]

San Carlos, Nicaragua, since 1989.[58]

Beşiktaş, Turkey, since 2003.[59]

Beşiktaş, Turkey, since 2003.[59]

Riverside, California, US, since 2011.[60]

Riverside, California, US, since 2011.[60]

Further partnerships

Venzone, Italy[61]

Venzone, Italy[61]

Shenzhen, China[62]

Shenzhen, China[62]

Richmond, Virginia, US[63]

Richmond, Virginia, US[63]

Cumiana, Italy[64]

Cumiana, Italy[64]

Erlangen is also the base of the Deutsch-Französisches Institut.[65]

Environmental protection

Environmental protection and nature conservation have enjoyed a high status in Erlangen since the beginning of the environmental movement in Germany in the early 1970s. A number of national and international awards attest to the success of these efforts. In 1988 the city was awarded the title "Partner of the European Environmental Year 1987/88" and in 1990 and 1991 the title "Federal Capital for Nature and Environmental Protection". The year 2007 was proclaimed the environmental year by the city administration with the motto "Natürlich ERLANGEN" (German for "natural/organic Erlangen"). One focus is the expansion of photovoltaics. From 2003 to 2011, the installed capacity of photovoltaic systems in Erlangen has increased more than twentyfold to 16,700 kW, covering more than 2.0 % of Erlangen's electricity requirements annually. Erlangen participates in the so-called Solarbundesliga (Federal Solar League). In the competition between cities, Erlangen reached third place in 2012[66] and second in the European Solar League.[67]

Since 2007, Erlangen has been the first city in Germany in which every school has its own solar system installed. The data of the solar systems at the schools are presented in the so-called climate protection school atlas on the Internet.[68] In 2011, a solar city map was set up on the Internet in which installed solar systems could be entered.[69]

Traffic

As early as the 1970s, ground work was being made for today's high share of bicycles in total traffic through a bicycle-friendly transport policy of then mayor Dietmar Hahlweg.[70] He paid particular attention to the introduction of cycling lanes on pedestrian paths. Throughout the entire population the bicycle is a common means of transport. Cyclers wearing suits and carrying briefcases are not an unusual sight. In the past, Erlangen and Münster regularly fought over the title of the most bicycle-friendly city in Germany.

With the use of natural gas buses in public transport, the Erlangen municipal utilities have also made a contribution to reducing CO2 emissions and particulate matter. Furthermore, there have been pushes from both SPD and CSU politicians to introduce electric busses into the city's fleet.[71][72] However, despite both Nuremberg and Fürth having already introduced such vehicles, there are no concrete plans for Erlangen to follow suit.[73][74]

Nature and landscape conservation

In the city area, two areas have been declared nature reserves (NSG) and thus enjoy the highest protection for plants and animals in accordance with Article 7 of the Bavarian Nature Conservation Act. These are:

- The Brucker Lache wetland biotope, designated a nature reserve in 1964, was extended in 1984 from its original 76 ha to 110 ha.[75] To the south of the nature reserve lies the Tennenlohe Forest Experience Centre, one of nine forest experience centres run by the Bavarian Forest Administration.[76]

- The nature reserve Exerzierplatz, a 25 ha sandy biotope, which was established in October 2000 is part of the Franconian sand axis.[77]

In addition to the nature reserves, Erlangen has 21 landscape reserves with a total area of 3538 ha, i.e. almost half of the entire city area. In contrast to nature reserves, these focus on the protection of special landscapes and their recreational value as well as the preservation of an efficient natural balance. Landscape reserves include[78][79]:

- The Holzweg (German for wooden path) in Büchenbach, a traditional connection path between Büchenbach and the Mönau forest area, where the inhabitants of Büchenbach supplied themselves with wood for centuries. This has created a hollow path sunken lane edges are overgrown with species-rich low-nutrient grassland vegetation.

- The Calcareous grassland on the so-called "Riviera", a footpath along the Schwabach (Rednitz). This area was declared a protected landscape area at the beginning of 2000.

- The Hutgraben Winkelfelder and Wolfsmantel (186 ha), a watercourse springing in a slope basin west of Kalchreuth, which flows into the Regnitz west of Eltersdorf. This area was declared a protected landscape area in 1983.

- The Bimbachtal, located in southwestern Büchenbach, was declared a landscape conservation area in 1983.

- The 56 ha sized area of Grünau

- The area around the Great Bishop's Pond (Dechsendorfer Weiher) (169 ha)

- The Mönau (570 ha)

- The Dechsendorf Lohe (70 ha)

- The Seebachgrund (112 ha)

- The Moorbach valley (50 ha)

- The Regnitz valley (883 ha)

- The Meilwald forest with ice pit (224 ha)

- The Schwabach valley (66 ha)

- The Steinforst ditch with the Kosbach pond and permanent forest strip east of the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal (157 ha)

- The Rittersbach creek (66 ha)

- The preservation strip on both sides of the A3 motorway (47 ha)

- The monastery forest (197 ha)

- The Aurach valley (182 ha)

- Römerreuth and surroundings (110 ha)

- The Bachgraben ditch (9 ha)

- The Brucker Lache (331 ha)

Notable residents

Though a small village for much of its history and now only a small city of only 100k inhabitants, Erlangen has made significant contributions to the world, primarily through its many Lutheran theologians, to its University of Erlangen-Nuremberg scholars, and the Siemens AG pioneers in science and technology.

Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius

Johann von Kalb

Georg Simon Ohm

Karl Daniel Heinrich Rau 1862

Among its noted residents are:

Johann de Kalb (1721–1780), – Soldier, War of Austrian Succession, Seven Years' War, Major General in the American Revolutionary War, namesake of many American towns

Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller (1725–1776), – zoologist, known to the classification of several new species, especially birds

Eugenius Johann Christoph Esper (1742–1810), – scientist, botanist, first to begin research into Paleopathology

Johann Schweigger – (1779–1857), chemist, physicist, mathematician, named "Chlorine", and invented the Galvanometer

August Friedrich Schweigger (1783–1921), – botanist, zoologist, known for taxonomy including the discovery of several turtle species

Georg Ohm – (1789–1854), German scientist, famous for Ohm's Law regarding electric current, and the measurement unit Ohm

Karl Heinrich Rau – (1792–1870), economist, published an influential encyclopedia of all "relevant" economic knowledge of his time

Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius – (1794–1868), botanist, explorer, famous expedition into Brazil (1817–1820)

Adolph Wagner – (1835–1917), economist, founding proponent of Academic Socialism and State Socialism

Paul Zweifel (1848–1927), – gynecologist, proved that the fetus was metabolically active, paving the way for new fetal research

Emmy Noether – (1882–1935), mathematician, groundbreaking work on abstract algebra and theoretical physics

Fritz Noether (1884–1941), – mathematician, political prisoner, younger brother of Emmy Noether, imprisoned in Soviet Russia

Ernst Penzoldt – (1892–1955), artist, famous German author, painter, and sculptor

Eduard Hauser (soldier) (1895–1961), – German officer, general in World War II,

Heinrich Welker – (1912–1981), theoretical physicist, made numerous inventions in the early electrical engineering fields

Rudolf Fleischmann (1903–2002), – scientist, nuclear physicist, member of the Uranium Club, theorist on isotope separation

Bernhard Plettner – (1914–1997), electrical engineer and Business Administration, CEO for Siemens AG (1971–1981)

Helmut Zahn (1916–2004), – scientist, chemist, one of the first to discover the properties of Insulin

Walter Krauß (1917–1943), – Luftwaffe officer

Hans Lotter (1917–2008), – officer in World War II, escaped from POW camp and wrote memoirs about it

Georg Nees – (1926–2016), Graphic Artist, expanded ALGOL computer language, pioneer in digital art and sculptures

Elke Sommer – (born 1940), entertainer, Golden Globe Award winning actress from television and film, early Playboy playmate

Heinrich von Pierer – (born 1941), Business Administration, CEO for Siemens AG (1992–2005), advisor to numerous governmental figures

Gerhard Frey – (born 1944), mathematician, worked on Elliptic Curve and helped prove Fermat's Last Theorem

Karl Meiler – (1949–2014), tennis player, moderately successful in Doubles Tennis in the 1970s.

Karlheinz Brandenburg – (born 1954), sound engineer, contributor to the invention of the format MPEG Audio Layer III, or MP3

Klaus Täuber – (born 1958), footballer, played for several Bundesliga teams from the mid 1970s–1980s, managed at lower levels

Lothar Matthäus – (born 1961), German Football legend, World Cup Winning Captain, Bayern Captain, first FIFA World Player of the Year

Willi Kalender – medical physicist, pioneer in CT Scan technology and research into numerous diseases

Jürgen Teller – (born 1964), fine art and fashion photography, worked for numerous magazines and designers, often with Björk

Hisham Zreiq – (born 1968), award-winning Palestinian Christian Independent filmmaker, poet and visual artist.

Peter Wackel – (born 1977), singer, with 6 albums and over 25 singles, he has a niche singing Schlager musik

Flula Borg – (born 1982), entertainer, DJ, hip-hop artist, internet sensation, film critic

Michael Buehl – (born 1962), professor of chemistry, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK

For a more complete list, visit Category:People from Erlangen

References

^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2018 (4. Quartal)". DESTATIS. Archived from the original on 10 March 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes". Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung (in German). September 2018.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-10-27). "Bevölkerung". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-10-27.

^ "Begründung – Natur und Landschaft" (PDF). Nuernberg.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Regnitz River | river, Germany". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-18). "Sozialstruktur in den Bezirken". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Kosbach, Häusling und Steudach wurden vor 40 Jahren eingemeindet" (PDF). lehninger.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Chronik Eltersdorf". www.sk-eltersdorf.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ www.lexolino.de. "lexolino.de – Erlangen in Geographie,Kontinente,Europa,Staaten,Deutschland,Städte". www.lexolino.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ ab Weißmüller, Wolfgang (2002). Vorgeschichte im Erlanger Raum. Begleitheft zur Dauerausstellung. Stadtmuseum Erlangen.

^ "Dauerausstellung". www.erlangen.de (in German). 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ "Sachverständiger Gutachter Wertermittlung von Immobilien". www.immobiliensachverstaendige-erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ "Kosbacher Altar im "Geheimen Gongland" › Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ "Der Kosbacher Altar erzählt" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ Roth, Matthias. "Kosbacher Altar". www.franken-tour.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

^ "Ausführliche Dokumentation zur Fundstelle Kosbach". uni-erlangen.de.

^ abcdef Jakob, Andreas (1990). Die Entwicklung der Altstadt Erlangen, Jahrbuch für fränkische Landesforschung. Neustadt a. d. Aisch. pp. 37, 95–96, 101. ISBN 978-3-7686-9108-6.

^ "dMGH | Band | Diplomata [Urkunden] (DD)O II / O III: Otto II. und Otto III. (DD O II / DD O III)| Diplome". www.dmgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

^ "dMGH | Band | Diplomata [Urkunden] (DD)H II: Heinrich II. und Arduin (DD H II) | Diplome". www.mgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

^ "dMGH|Band |Diplomata Urkunden (DD) H II: Heinrich II. und Arduin(DD H II)| Diplome". www.mgh.de. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

^ abc Lammers, Ferdinand (1834). Geschichte der Stadt Erlangen. Erlangen. pp. 17, 27, 183, 189.

^ ab Bischoff, Johannes (1984). Die Siedlung in den ersten Jahrhunderten. Munich: Alfred Wendehorst. pp. 20, 23. ISBN 978-3-406-09412-5.

^ abc Endres, Rudolf (1984). Erlangen. Geschichte der Stadt in Darstellung und Bilddokumenten. Munich: Alfred Wendehorst. pp. 31, 33, 40, 41.

^ Deuerlein, Ernst G. (1967). Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Familie derer von Erlangen. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Landesforschung. p. 165.

^ ab Nürmberger, Bernd (2003). Erlangen um 1530. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Landesforschung. pp. 199, 288.

^ Bischoff (1961). Erlangens Einwohner 1616 und 1619. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Landesforschung. p. 49.

^ Döllner, Max (1950). Entwicklungsgeschichte der Stadt Neustadt an der Aisch bis 1933. Neustadt an der Aisch: Ph. C. W. pp. 307, 308.

^ Tempel, Pia (1990). Vermessung historischer Keller in der Erlanger Altstadt. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Familie derer von Erlangen. pp. 201–205.

^ Wangerin (1991). Erlangens spätmittelalterliche Wehrmauer zwischen Katzenturm und Altstädter Kirche. Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Landesforschung. pp. 249–254.

^ Jakob, Andreas (1986). Die Neustadt Erlangen. Planung und Entstehung.

^ Jakob, Andreas (2006). Der Ort stieg aus seiner Asche viel schöner empor.

^ Müssel, Karl (1993). Bayreuth in acht Jahrhunderten. Bayreuth: Gondrom. p. 139. ISBN 3-8112-0809-8.

^ "Deutschland: Wahl zum 8. Reichstag 1933". www.gonschior.de. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

^ Jakob, Andreas (2011). Die Nacht, in der die Judenaktion stattfand ….

^ Erlangen im Nationalsozialismus. Stadtmuseum Erlangen. 1983.

^ Statistisches Jahrbuch deutscher Gemeinden. Braunschweig: Deutscher Städtetag. 1952. p. 384.

^ "Bundeshauptstadt für Natur- und Umweltschutz". Erlanger Stadtlexikon. 2002.

^ "Erlangen". Süddeutsche Zeitung. 1993-05-19.

^ "Remember "Ferris Barracks": Die US-Army in Erlangen". www.nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-26.

^ "History of FAU › Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg". fau.eu. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

^ Übersicht des Personalstandes der Königlich Bayerischen Friedrich-Alexanders-Universität Erlangen: nebst dem Verzeichnisse der Studierenden. 1869/70. WS (in German). 1869.

^ "Students › Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg". fau.eu. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

^ Abele-Brehm, Andrea (2003-11-04). "100 Jahre akademische Frauenbildung in Bayern und Erlangen - Rückblick und Perspektiven" (PDF). Erlangen University Speeches: 4, 6.

^ abcde Erlangen, Stadt (2019-04-04). "Bevölkerung". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-04-07.

^ ab Schieber, Martin (2002). Erlangen: eine illustrierte Geschichte der Stadt. Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 133. ISBN 3 406 48913 3.

^ Bischoff, Johannes (1976). "Die Königsmühle an der Gründlach. Ein historischer Rückblick zu ihrer Umgliederung von der Stadt Fürth in die Stadt Erlangen am 1. Januar 1977, mit vergleichenden Daten zur Geschichte der Mittelmühle in Nürnberg-Kleingründlach und der Mühle in Erlangen-Bruck". Erlanger Bausteine zur fränkischen Heimatforschung. 23: 49–69.

^ "Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit". Stadt Erlangen. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

^ Jakob, Andreas (2007-09-09). "Das Himmelreich zu Erlangen – offen aus Tradition?" (PDF). erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Erlangen – Bayerns achtgrößte Stadt | Erlanger Historikerseite". www.erlangerhistorikerseite.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2017" (PDF). erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Im Untergrund von Erlangen: Die Kellerführung vom Entlas Keller // hombertho.de // 2010, Bergkerwa, Bier, Erlangen, Fotos, Kellerführung, Mai, Party". Hombertho.de. 2010-04-18. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

^ "Der Entlaskeller – Kellerführungen". Entlaskeller.de. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Städtepartnerschaften". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "45 Jahre Erlangen – Rennes" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Wladimir". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Erlangen" (in German). 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Stoke-on-Trent". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "San Carlos". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Beşiktaş". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "Erlangen besiegelt Städtepartnerschaft mit Riverside" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Städtepartnerschaften". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Shenzhen". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2018-06-19). "Partnerstädte – Archiv". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Germany, nordbayern.de, Nürnberg,. "Erlangen besiegelt Freundschaft mit Cumiana" (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "IMPRESSUM". www.dfi-erlangen.de. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ "Herbstmeister der Solarbundesliga stehen fest". Solarthemen (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "In der „Champions-League" für erneuerbare Energien". www.nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Unabhängiges Institut für Umweltfragen (UfU) – Umweltwissenschaft. Bürgernah". Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Solarstadtplan Erlangen". solarstadtplan.de. 2011-05-07. Archived from the original on 2015-10-21. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2019-02-21). "Stadt und Leute". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Steht die Energiewende auf der Kippe?". www.nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Ungleiche Ansichten: E-Busse in Erlangen". www.nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Stadt sollte 80 Prozent-E-Bus-Förderung schnell für Erlangen nutzen!". marktspiegel.de. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Fürths erster E-Bus hat sich bewährt". www.nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Joachim Herrmann MdL - 50 Jahre Naturschutzgebiet 'Brucker Lache' in Erlangen". www.joachimherrmann.de. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Walderlebniszentrum Tennenlohe". www.alf-fu.bayern.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2019-02-21). "Mobilität und öffentlicher Raum". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

^ "Grüne Liste Landschaftsschutzgebiete in Mittelfranken" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-02-21.

^ Erlangen, Stadt (2019-02-21). "Naturschutz". www.erlangen.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-02-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erlangen. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Erlangen. |

Official website (in German)

(in German)

erlangeninfo.de Erlangen City Guide- University of Erlangen

- Ferris Barracks – former US Army Kaserne in Erlangen