Proline

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

IUPAC name Proline | |

Systematic IUPAC name Pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

Beilstein Reference | 80812 |

ChEBI |

|

ChEMBL |

|

ChemSpider |

|

DrugBank |

|

ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.264 |

EC Number | 210-189-3 |

Gmelin Reference | 26927 |

KEGG |

|

MeSH | Proline |

PubChem CID |

|

RTECS number | TW3584000 |

UNII |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula | C5H9NO2 |

Molar mass | 115.13 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Transparent crystals |

Melting point | 205 to 228 °C (401 to 442 °F; 478 to 501 K) (decomposes) |

Solubility | 1.5g/100g ethanol 19 degC[2] |

log P | -0.06 |

Acidity (pKa) | 1.99 (carboxyl), 10.96 (amino)[3] |

| Hazards | |

Safety data sheet | See: data page |

S-phrases (outdated) | S22, S24/25 |

Supplementary data page | |

Structure and properties | Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. |

Thermodynamic data | Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Infobox references | |

Proline (symbol Pro or P)[4] is a proteinogenic amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated NH2+ form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain pyrrolidine, classifying it as a nonpolar (at physiological pH), aliphatic amino acid. It is non-essential in humans, meaning the body can synthesize it from the non-essential amino acid L-glutamate. It is encoded by all the codons starting CC (CCU, CCC, CCA, and CCG).

Proline is the only proteinogenic amino acid with a secondary amine, in that the alpha-amino group is attached directly to the main chain, making the α carbon a direct substituent of the side chain.

Contents

1 History and etymology

2 Biosynthesis

3 Biological activity

4 Properties in protein structure

5 Cis-trans isomerization

6 Uses

7 Specialties

8 History

9 Synthesis

10 See also

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

History and etymology

Proline was first isolated in 1900 by Richard Willstätter who obtained the amino acid while studying N-methylproline. The year after Emil Fischer published the synthesis of proline from phthalimide propylmalonic ester.[5] The name proline comes from pyrrolidine, one of its constituents.[6]

Biosynthesis

Proline is biosynthetically derived from the amino acid L-glutamate. Glutamate-5-semialdehyde is first formed by glutamate 5-kinase (ATP-dependent) and glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (which requires NADH or NADPH). This can then either spontaneously cyclize to form 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid, which is reduced to proline by pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (using NADH or NADPH), or turned into ornithine by ornithine aminotransferase, followed by cyclisation by ornithine cyclodeaminase to form proline.[7]

Zwitterionic structure of both proline enantiomers: (S)-proline (left) and (R)-proline

Biological activity

L-Proline has been found to act as a weak agonist of the glycine receptor and of both NMDA and non-NMDA (AMPA/kainate) ionotropic glutamate receptors.[8][9][10] It has been proposed to be a potential endogenous excitotoxin.[8][9][10] In plants, proline accumulation is a common physiological response to various stresses but is also part of the developmental program in generative tissues (e.g. pollen).[11]

Properties in protein structure

The distinctive cyclic structure of proline's side chain gives proline an exceptional conformational rigidity compared to other amino acids. It also affects the rate of peptide bond formation between proline and other amino acids. When proline is bound as an amide in a peptide bond, its nitrogen is not bound to any hydrogen, meaning it cannot act as a hydrogen bond donor, but can be a hydrogen bond acceptor.

Peptide bond formation with incoming Pro-tRNAPro is considerably slower than with any other tRNAs, which is a general feature of N-alkylamino acids.[12] Peptide bond formation is also slow between an incoming tRNA and a chain ending in proline; with the creation of proline-proline bonds slowest of all.[13]

The exceptional conformational rigidity of proline affects the secondary structure of proteins near a proline residue and may account for proline's higher prevalence in the proteins of thermophilic organisms. Protein secondary structure can be described in terms of the dihedral angles φ, ψ and ω of the protein backbone. The cyclic structure of proline's side chain locks the angle φ at approximately −65°.[14]

Proline acts as a structural disruptor in the middle of regular secondary structure elements such as alpha helices and beta sheets; however, proline is commonly found as the first residue of an alpha helix and also in the edge strands of beta sheets. Proline is also commonly found in turns (another kind of secondary structure), and aids in the formation of beta turns. This may account for the curious fact that proline is usually solvent-exposed, despite having a completely aliphatic side chain.

Multiple prolines and/or hydroxyprolines in a row can create a polyproline helix, the predominant secondary structure in collagen. The hydroxylation of proline by prolyl hydroxylase (or other additions of electron-withdrawing substituents such as fluorine) increases the conformational stability of collagen significantly.[15] Hence, the hydroxylation of proline is a critical biochemical process for maintaining the connective tissue of higher organisms. Severe diseases such as scurvy can result from defects in this hydroxylation, e.g., mutations in the enzyme prolyl hydroxylase or lack of the necessary ascorbate (vitamin C) cofactor.

Cis-trans isomerization

Peptide bonds to proline, and to other N-substituted amino acids (such as sarcosine), are able to populate both the cis and trans isomers. Most peptide bonds overwhelmingly adopt the trans isomer (typically 99.9% under unstrained conditions), chiefly because the amide hydrogen (trans isomer) offers less steric repulsion to the preceding Cα atom than does the following Cα atom (cis isomer). By contrast, the cis and trans isomers of the X-Pro peptide bond (where X represents any amino acid) both experience steric clashes with the neighboring substitution and have a much lower energy difference. Hence, the fraction of X-Pro peptide bonds in the cis isomer under unstrained conditions is significantly elevated, with cis fractions typically in the range of 3-10%.[16] However, these values depend on the preceding amino acid, with Gly[17] and aromatic[18] residues yielding increased fractions of the cis isomer. Cis fractions up to 40% have been identified for Aromatic-Pro peptide bonds.[19]

From a kinetic standpoint, cis-trans proline isomerization is a very slow process that can impede the progress of protein folding by trapping one or more proline residues crucial for folding in the non-native isomer, especially when the native protein requires the cis isomer. This is because proline residues are exclusively synthesized in the ribosome as the trans isomer form. All organisms possess prolyl isomerase enzymes to catalyze this isomerization, and some bacteria have specialized prolyl isomerases associated with the ribosome. However, not all prolines are essential for folding, and protein folding may proceed at a normal rate despite having non-native conformers of many X-Pro peptide bonds.

Uses

Proline and its derivatives are often used as asymmetric catalysts in proline organocatalysis reactions. The CBS reduction and proline catalysed aldol condensation are prominent examples.

In brewing, proteins rich in proline combine with polyphenols to produce haze (turbidity).[20]

L-Proline is an osmoprotectant and therefore is used in many pharmaceutical, biotechnological applications.

The growth medium used in plant tissue culture may be supplemented with proline. This can increase growth, perhaps because it helps the plant tolerate the stresses of tissue culture.[21][better source needed] For proline's role in the stress response of plants, see § Biological activity.

Specialties

Proline is one of the two amino acids that do not follow along with the typical Ramachandran plot, along with glycine. Due to the ring formation connected to the beta carbon, the ψ and φ angles about the peptide bond have fewer allowable degrees of rotation. As a result, it is often found in "turns" of proteins as its free entropy (ΔS) is not as comparatively large to other amino acids and thus in a folded form vs. unfolded form, the change in entropy is less. Furthermore, proline is rarely found in α and β structures as it would reduce the stability of such structures, because its side chain α-N can only form one hydrogen bond.

Additionally, proline is the only amino acid that does not form a blue/purple colour when developed by spraying with ninhydrin for uses in chromatography. Proline, instead, produces an orange/yellow colour.

History

Richard Willstätter synthesized proline by the reaction of sodium salt of diethyl malonate with 1,3-dibromopropane in 1900. In 1901, Hermann Emil Fischer isolated proline from casein and the decomposition products of γ-phthalimido-propylmalonic ester.[22]

Synthesis

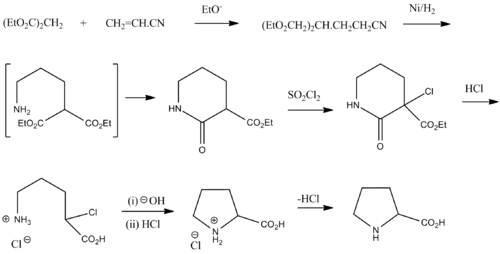

Racemic proline can be synthesized from diethyl malonate and acrylonitrile:[23]

See also

- Hyperprolinemia

- Inborn error of metabolism

- Prolidase deficiency

- Prolinol

References

^ Pubchem. "Proline". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^

H.-D. Belitz; W. Grosch; P. Schieberle. Food Chemistry. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-540-69933-0. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15.

^ Nelson, D.L., Cox, M.M., Principles of Biochemistry. NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

^ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

^ "Proline". Archived from the original on 2015-11-27.

^ "proline". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition. Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

^ Lehninger, Albert L.; Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2000). Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-153-6..

^ ab Ion Channel Factsbook: Extracellular Ligand-Gated Channels. Academic Press. 16 November 1995. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-08-053519-7. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016.

^ ab Henzi V, Reichling DB, Helm SW, MacDermott AB (1992). "L-proline activates glutamate and glycine receptors in cultured rat dorsal horn neurons". Mol. Pharmacol. 41 (4): 793–801. PMID 1349155.

^ ab Orhan E. Arslan (7 August 2014). Neuroanatomical Basis of Clinical Neurology, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-4398-4833-3. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

^ Verbruggen N, Hermans C (2008). "Proline accumulation in plants: a review". Amino Acids. 35 (4): 753–759. doi:10.1007/s00726-008-0061-6. PMID 18379856.

^ Pavlov, Michael Y; Watts, Richard E; Tan, Zhongping; Cornish, Virginia W; Ehrenberg, Måns; Forster, Anthony C (2010), "Slow peptide bond formation by proline and other N-alkylamino acids in translation", PNAS, 106 (1): 50–54, doi:10.1073/pnas.0809211106, PMC 2629218, PMID 19104062.

^ Buskirk, Allen R.; Green, Rachel (2013). "Getting Past Polyproline Pauses". Science. 339 (6115): 38–39. doi:10.1126/science.1233338. PMC 3955122. PMID 23288527. Archived from the original on 2014-04-15.

^ Morris, Anne (1992). "Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates". Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 12: 345–364. doi:10.1002/prot.340120407. PMID 1579569.

^ Szpak, Paul (2011). "Fish bone chemistry and ultrastructure: implications for taphonomy and stable isotope analysis". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (12): 3358–3372. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.07.022. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18.

^ Alderson, T.R.; Lee, J.H.; Charlier, C.; Ying, J. & Bax, A. (2017). "Propensity for cis-proline formation in unfolded proteins" (PDF). ChemBioChem. 19: 37–42. doi:10.1002/cbic.201700548. Retrieved Nov 27, 2017.

^ Sarkar, S.K.; Young, P.E.; Sullivan, C.E. & Torchia, D.A. (1984). "Detection of cis and trans X-Pro peptide bonds in proteins by 13C NMR: Application to collagen" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.15.4800. PMC 391578. Archived from the original on 2018-05-08. Retrieved Nov 27, 2017.

^ Thomas, K.M.; Naduthambi, D. & Zondlo, N.J. (2006). "Electronic Control of Amide cis−trans Isomerism via the Aromatic−Prolyl Interaction" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128: 2216–2217. doi:10.1021/ja057901y. Retrieved Nov 27, 2017.

^ Gustafson, C.L.; Parsely, N.C.; Asimgil, H.; et al. (2017). "A Slow Conformational Switch in the BMAL1 Transactivation Domain Modulates Circadian Rhythms". Molecular Cell. 66: 447–457.e7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.011. Retrieved Nov 29, 2017.CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

^ K.J. Siebert, "Haze and Foam","Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-11. Retrieved 2010-07-13.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) Accessed July 12, 2010.

^ Pazuki, A; Asghari, J; Sohani, M; Pessarakli, M & Aflaki, F (2015). "Effects of Some Organic Nitrogen Sources and Antibiotics on Callus Growth of Indica Rice Cultivars" (PDF). Journal of Plant Nutrition. 38 (8): 1231–1240. doi:10.1080/01904167.2014.983118. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

^ R.H.A. Plimmer (1912) [1908], R.H.A. Plimmer & F.G. Hopkins, ed., The chemical composition of the proteins, Monographs on biochemistry, Part I. Analysis (2nd ed.), London: Longmans, Green and Co., p. 130, retrieved September 20, 2010

^ Vogel, Practical Organic Chemistry 5th edition

Further reading

Balbach, J.; Schmid, F. X. (2000), "Proline isomerization and its catalysis in protein folding", in Pain, R. H., Mechanisms of Protein Folding (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, pp. 212–49, ISBN 0-19-963788-1.- For a thorough scientific overview of disorders of proline and hydroxyproline metabolism, one can consult chapter 81 of OMMBID Charles Scriver, Beaudet, A.L., Valle, D., Sly, W.S., Vogelstein, B., Childs, B., Kinzler, K.W. (Accessed 2007). The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill. - Summaries of 255 chapters, full text through many universities. There is also the OMMBID blog.

External links

- Proline MS Spectrum

- Proline biosynthesis

- Proline biosynthesis