Niger–Congo languages

Niger–Congo languages

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| Niger–Congo | |

|---|---|

| Niger–Kordofanian | |

| Geographic distribution | Africa |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions |

|

ISO 639-2 / 5 | nic |

| Glottolog | None |

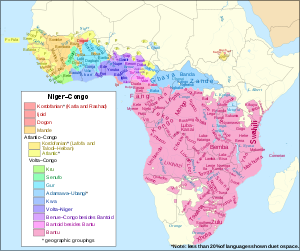

Map showing the distribution of major Niger–Congo languages. Pink-red is the Bantu subfamily. | |

The Niger–Congo languages constitute one of the world's major language families and Africa's largest in terms of geographical area, number of speakers and number of distinct languages.[1] It is generally considered to be the world's largest language family in terms of distinct languages,[2][3] ahead of Austronesian, although this is complicated by the ambiguity about what constitutes a distinct language; the number of named Niger–Congo languages listed by Ethnologue is 1,540.[4] It is the third largest language family in the world by number of native speakers, comprising around 700 million people as of 2015. Within Niger–Congo, the Bantu languages alone account for 350 million people (2015), or half the total Niger–Congo speaking population.

One of the characteristics common to most Niger–Congo languages (the Atlantic–Congo languages) is the use of a noun class system.[5] The most widely spoken Niger–Congo languages by number of native speakers are Yoruba, Igbo, Fula and Shona. The most widely spoken by number of speakers is Swahili.[6]

While the ultimate genetic unity of Niger–Congo is widely accepted (aside from Dogon, Mande and a few other languages), the internal cladistic structure of Niger–Congo is not well established. Its primary branches are Dogon, Mande, Ijo, Katla, Rashad and Atlantic–Congo.

Contents

1 Origin

2 Major branches

2.1 Atlantic–Congo

2.2 Other

3 Classification history

3.1 Early classifications

3.2 Westermann, Greenberg and beyond

3.3 Reconstruction

3.4 Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan

4 Common features

4.1 Phonology

4.1.1 Consonants

4.1.2 Vowels

4.1.3 Nasality

4.1.4 Tone

4.2 Morphosyntax

4.2.1 Noun classification

4.2.2 Verbal extensions

4.2.3 Word order

5 Notes

6 Further reading

7 External links

Origin [edit]

The language family most likely originated in or near the area where these languages were spoken prior to Bantu expansion (i.e. West Africa or Central Africa). Its expansion may have been associated with the expansion of Sahel agriculture in the African Neolithic period, following the desiccation of the Sahara in c. 3500 BCE.[7][8]

According to Roger Blench (2004), all specialists in Niger–Congo languages believe the languages to have a common origin, rather than merely constituting a typological classification, for reasons including their shared noun-class system, shared verbal extensions and shared basic lexicon.[9] Similar classifications to Niger–Congo have been made ever since Diedrich Westermann in 1922.[10]Joseph Greenberg continued that tradition, making it the starting point for modern linguistic classification in Africa, with some of his most notable publications going to press starting in the 1960s.[11] However, there has been active debate for many decades over the appropriate subclassifications of the languages in this language family, which is a key tool used in localising a language's place of origin.[12] No definitive "Proto-Niger–Congo" lexicon or grammar has been developed for the language family as a whole.

An important unresolved issue in determining the time and place where the Niger–Congo languages originated and their range prior to recorded history is this language family's relationship to the Kordofanian languages, now spoken in the Nuba mountains of Sudan, which is not contiguous with the remainder of the Niger–Congo-language-speaking region and is at the northeasternmost extent of the current Niger–Congo linguistic region. The current prevailing linguistic view is that Kordofanian languages are part of the Niger–Congo language family and that these may be the first of the many languages still spoken in that region to have been spoken in the region.[13] The evidence is insufficient to determine if this outlier group of Niger–Congo language speakers represent a prehistoric range of a Niger–Congo linguistic region that has since contracted as other languages have intruded, or if instead, this represents a group of Niger–Congo language speakers who migrated to the area at some point in prehistory where they were an isolated linguistic community from the beginning.

There is more agreement regarding the place of origin of Benue–Congo, the largest subfamily of the group. Within Benue–Congo, the place of origin of the Bantu languages as well as time at which it started to expand is known with great specificity. Blench (2004), relying particularly on prior work by Kay Williamson and P. De Wolf, argued that Benue–Congo probably originated at the confluence of the Benue and Niger Rivers in central Nigeria.[9][14][15][16][17][18] These estimates of the place of origin of the Benue-Congo language family do not fix a date for the start of that expansion, other than that it must have been sufficiently prior to the Bantu expansion to allow for the diversification of the languages within this language family that includes Bantu.

The classification of the relatively divergent family of the Ubangian languages, centred in the Central African Republic, as part of the Niger–Congo language family is disputed. Ubangian was grouped with Niger–Congo by Greenberg (1963), and later authorities concurred,[19] but it was questioned by Dimmendaal (2008).[20]

The Bantu expansion, beginning around 1000 BC, swept across much of Central and Southern Africa, leading to the extinction of most of the indigenous Pygmy and Bushmen (Khoisan) populations there.[21]

Major branches[edit]

The following is an overview of the language groups usually included in Niger–Congo. The genetic relationship of some branches is not universally accepted, and the cladistic connection between those who are accepted as related may also be unclear.

The core phylum of the Niger–Congo group are the Atlantic–Congo languages. The non-Atlantic–Congo languages within Niger–Congo are grouped as Dogon, Mande, Ijo (sometimes with Defaka as Ijoid), Katla and Rashad.

Atlantic–Congo[edit]

Atlantic–Congo combines the Atlantic languages, which do not form one branch, and Volta–Congo. It comprises more than 80% of the Niger–Congo speaking population, or close to 600 million people (2015).

The proposed Savannas group combines Adamawa, Ubangian and Gur. Outside of the Savannas group, Volta–Congo comprises Kru, Kwa (or "West Kwa"), Volta–Niger (also "East Kwa" or "West Benue–Congo") and Benue–Congo (or "East Benue–Congo"). Volta–Niger includes the two largest languages of Nigeria, Yoruba and Igbo. Benue–Congo includes the Southern Bantoid group, which is dominated by the Bantu languages, which account for 350 million people (2015), or half the total Niger–Congo speaking population.

The strict genetic unity of any of these subgroups may themselves be under dispute. For example, Roger Blench (2012) argued that Adamawa, Ubangian, Kwa, Bantoid, and Bantu are not coherent groups.[22]

Glottolog (2013) does not accept that the Kordofanian branches (Lafofa, Talodi and Heiban) or the difficult-to-classify Laal language have been demonstrated to be Atlantic–Congo languages. It otherwise accepts the family but not its inclusion within a broader Niger–Congo.

The Atlantic–Congo group is characterised the noun class systems of its languages. Atlantic–Congo largely corresponds to Mukarovsky's "Western Nigritic" phylum.[23]

- Atlantic

The polyphyletic Atlantic group accounts for about 35 million speakers as of 2016, mostly accounted for by Fula and Wolof speakers. Atlantic is not considered to constitute a valid group.

Senegambian languages: includes Wolof, spoken in Senegal, and Fula, spoken across the Sahel.

Bak languages, sometimes grouped with Senegambian- Mel languages

- Limba language

- Gola language

- Volta–Congo

North–Volta

Kru: languages of the Kru people in West Africa; includes Bété, Nyabwa, and Dida.

Adamawa–Ubangi:

Adamawa: close to 100 languages and dialects scattered across the Adamawa Plateau, spoken by an estimated total of 1.6 million as of 1996; the largest is Mumuye, accounting for about a quarter of Adamawa speakers.

Ubangian: a group of minor languages spoken in the Central African Republic, grouped with Adamawa as "Adamawa–Ubangi".

Gur: about 70 languages spoken in the Sahel and Savanna regions of West Africa, accounting for some 20 million speakers (2010). The largest language of this group is Mossi (More, Mòoré), with about 8 million speakers as of 2010. Gur and Adamawa-Ubangi have also been grouped as Savannas languages.

Senufo: languages of the Senufo people (about 3 million speakers as of 2010), spoken in Ivory Coast and Mali, with a geographical outlier in Ghana; includes Senari and Supyire. Senufo has been placed traditionally within Gur but is now usually considered an early offshoot from Atlantic–Congo.

South–Volta

Kwa: a divergent group of languages of uncertain genetic unity, spoken along the Ivory Coast, across southern Ghana and in central Togo, with a total of some 40 million speakers (2010s). The largest language in this group is Akan, spoken in Ghana, with about 22 million speakers as of 2014, followed by Twi (9 million in 2015).

Volta–Niger (also known as "West Benue–Congo" or "East Kwa"): a large group of West African languages, accounting for roughly 110–120 million speakers (late 2010s).

Gbe: spoken in Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria, of which Ewe (7 million speakers in 2017) is the largest and best known.- "YEAI": a large group of languages centred on Nigeria, accounting for about 100 million speakers (late 2010s)

Yoruboid: 50 million speakers (2010s), including Yoruba (c. 40 million 2017)

Edoid: including Edo (5 million 2010s)- Akoko

Igboid: including Igbo (24 million 2011)

- "NOI":

Nupoid: c. 3 million (c. 1990 estimates)

Oko: a minor dialect continuum spoken in Kogi State

Idomoid: group of languages of central Nigeria, including Idoma with 1 to 2 million speakers (2010s)

Ayere–Ahan (moribund or extinct)

Benue–Congo (East Benue–Congo)

- Bantoid–Cross:

- Cross River

- "Bantoid":

Dakoid?

Fam?

Tikar?- Mambiloid

- Bendi

Southern Bantoid or "Wide Bantu": includes the far-flung Bantu languages spread across Sub-Saharan Africa in the Bantu expansion from c. 1000 BCE to 500 CE.

- Tivoid–Beboid: a large range of languages of southwestern Cameroon and southeastern Nigeria: Tivoid, Esimbi, East Beboid, West Beboid?, Momo?, Furu?, Buru?, Menchum?

Ekoid–Mbe

- Mamfe

- Grassfields

Jarawan–Mbam

(Narrow) Bantu: divided into Guthrie zones A–S, for a total of between 250 and 550 named languages.

- Central Nigerian (Platoid): Jukunoid, Kainji, Plateau

- other languages unclassified within Benue–Congo: Ukaan, Fali of Baissa, Tita.

- Bantoid–Cross:

Other[edit]

The putative Niger–Congo languages outside of the Atlantic–Congo family are centred in the upper Senegal and Niger river basins, south and west of Timbuktu (Mande, Dogon), Liberia (Kru), the Niger Delta (Ijoid), and fair to the east in south-central Sudan, around the Nuba Mountains (the Kordofanian families). They account for a total population of about 100 million (2015), mostly Mandé and Ijaw.

Mande: languages of the Mandé peoples, estimated at roughly 70 million as of 2016

Dogon: languages of the Dogon people of Mali, estimated at 1.6 million as of 2013. May have a noun-class system related to the Atlantic–Congo languages.

Bangime, spoken in Dogon country

Kru of Liberia and Ivory Coast

Siamou, once classified as Kru

Ijoid: Ijaw, the language of the Ijaw people (14 million as of 2011), plus the moribund Defaka language

The various Kordofanian languages are spoken in south-central Sudan, around the Nuba Mountains. "Kordofanian" is a geographic grouping, not a genetic one, named for the Kordofan region. These are minor languages, spoken by a total of about 100,000 people according to 1980s estimates.

- Talodi languages

- Heiban languages

- Lafofa languages

- Rashad languages

- Katla languages

The endangered or extinct Laal, Mpre and Jalaa languages are often assigned to Niger–Congo.

Overview map

Overview map of Nigeria and Cameroon

Table of demographic estimates in the same color code as the maps (est. 400 million speakers as of 2007)

Classification history[edit]

Early classifications[edit]

Niger–Congo as it is known today was only gradually recognized as a linguistic unit. In early classifications of the languages of Africa, one of the principal criteria used to distinguish different groupings was the languages' use of prefixes to classify nouns, or the lack thereof. A major advance came with the work of Sigismund Wilhelm Koelle, who in his 1854 Polyglotta Africana attempted a careful classification, the groupings of which in quite a number of cases correspond to modern groupings. An early sketch of the extent of Niger–Congo as one language family can be found in Koelle's observation, echoed in Bleek (1856), that the Atlantic languages used prefixes just like many Southern African languages. Subsequent work of Bleek, and some decades later the comparative work of Meinhof, solidly established Bantu as a linguistic unit.

In many cases, wider classifications employed a blend of typological and racial criteria. Thus, Friedrich Müller, in his ambitious classification (1876–88), separated the 'Negro' and Bantu languages. Likewise, the Africanist Karl Richard Lepsius considered Bantu to be of African origin, and many 'Mixed Negro languages' as products of an encounter between Bantu and intruding Asiatic languages.

In this period a relation between Bantu and languages with Bantu-like (but less complete) noun class systems began to emerge. Some authors saw the latter as languages which had not yet completely evolved to full Bantu status, whereas others regarded them as languages which had partly lost original features still found in Bantu. The Bantuist Meinhof made a major distinction between Bantu and a 'Semi-Bantu' group which according to him was originally of the unrelated Sudanic stock.

Westermann, Greenberg and beyond[edit]

Westermann's 1911 Die Sudansprachen. Eine sprachvergleichende Studie laid much of the basis for the understanding of Niger–Congo.

Westermann, a pupil of Meinhof, set out to establish the internal classification of the then Sudanic languages. In a 1911 work he established a basic division between 'East' and 'West'. A historical reconstruction of West Sudanic was published in 1927, and in his 1935 'Charakter und Einteilung der Sudansprachen' he conclusively established the relationship between Bantu and West Sudanic.

Joseph Greenberg took Westermann's work as a starting-point for his own classification. In a series of articles published between 1949 and 1954, he argued that Westermann's 'West Sudanic' and Bantu formed a single genetic family, which he named Niger–Congo; that Bantu constituted a subgroup of the Benue–Congo branch; that Adamawa–Eastern, previously not considered to be related, was another member of this family; and that Fula belonged to the West Atlantic languages. Just before these articles were collected in final book form (The Languages of Africa) in 1963, he amended his classification by adding Kordofanian as a branch co-ordinate with Niger–Congo as a whole; consequently, he renamed the family Congo–Kordofanian, later Niger–Kordofanian. Greenberg's work on African languages, though initially greeted with scepticism, became the prevailing view among scholars.[24]

Bennet and Sterk (1977) presented an internal reclassification based on lexicostatistics that laid the foundation for the regrouping in Bendor-Samuel (1989). Kordofanian was presented as one of several primary branches rather than being coordinate to the family as a whole, prompting re-introduction of the term Niger–Congo, which is in current use among linguists. Many classifications continue to place Kordofanian as the most distant branch, but mainly due to negative evidence (fewer lexical correspondences), rather than positive evidence that the other languages form a valid genealogical group. Likewise, Mande is often assumed to be the second-most distant branch based on its lack of the noun-class system prototypical of the Niger–Congo family. Other branches lacking any trace of the noun-class system are Dogon and Ijaw, whereas the Talodi branch of Kordofanian does have cognate noun classes, suggesting that Kordofanian is also not a unitary group.

Glottolog (2013) accepts the core with noun-class systems, the Atlantic–Congo languages, apart from the recent inclusion of some of the Kordofanian groups, but not Niger–Congo as a whole. They list the following as separate families:

- Atlantic–Congo, Mande, Dogon, Ijoid, Lafofa, Katla–Tima, Heiban, Talodi, Rashad.

Oxford Handbooks Online (2016) has indicated that the continuing reassessment of Niger-Congo's "internal structure is due largely to the preliminary nature of Greenberg’s classification, explicitly based as it was on a methodology that doesn’t produce proofs for genetic affiliations between languages but rather aims at identifying “likely candidates.”...The ongoing descriptive and documentary work on individual languages and their varieties, greatly expanding our knowledge on formerly little-known linguistic regions, is helping to identify clusters and units that allow for the application of the historical-comparative method. Only the reconstruction of lower-level units, instead of “big picture” contributions based on mass comparison, can help to verify (or disprove) our present concept of Niger-Congo as a genetic grouping consisting of Benue-Congo plus Volta-Niger, Kwa, Adamawa plus Gur, Kru, the so-called Kordofanian languages, and probably the language groups traditionally classified as Atlantic."[25]

The coherence of Niger-Congo as a language phylum is supported by Grollemund, et al. (2016), using computational phylogenetic methods.[26] The East/West Volta-Congo division, West/East Benue-Congo division, and North/South Bantoid division are not supported, whereas a Bantoid group consisting of Ekoid, Bendi, Dakoid, Jukunoid, Tivoid, Mambiloid, Beboid, Mamfe, Tikar, Grassfields, and Bantu is supported.

The Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP) also groups many Niger-Congo branches together.

Reconstruction[edit]

Proto-Niger–Congo (or Proto-Atlantic–Congo) has not been reconstructed, and few of the demonstrably coherent branches of it have been either. The major success has been several reconstructions of Proto-Bantu, which has consequently had an outsize influence on conceptions of what Proto-Niger–Congo may have been like. The only stage higher than Proto-Bantu that has been reconstructed is a pilot project by Stewart, who since the 1970s has reconstructed the common ancestor of the Potou–Tano and Bantu languages, without so far considering the hundreds of other languages which presumably descend from that same ancestor.[27]

Pozdniakov has reconstructed the numeral system.[28]

Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan[edit]

Over the years, several linguists have suggested a link between Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan, probably starting with Westermann's comparative work on the "Sudanic" family in which 'Eastern Sudanic' (now classified as Nilo-Saharan) and 'Western Sudanic' (now classified as Niger–Congo) were united. Gregersen (1972) proposed that Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan be united into a larger phylum, which he termed Kongo–Saharan. His evidence was mainly based on the uncertainty in the classification of Songhay, morphological resemblances, and lexical similarities. A more recent proponent was Roger Blench (1995), who puts forward phonological, morphological and lexical evidence for uniting Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan in a Niger–Saharan phylum, with special affinity between Niger–Congo and Central Sudanic. However, fifteen years later his views had changed, with Blench (2011) proposing instead that the noun-classifier system of Central Sudanic, commonly reflected in a tripartite general–singulative–plurative number system, triggered the development or elaboration of the noun-class system of the Atlantic–Congo languages, with tripartite number marking surviving in the Plateau and Gur languages of Niger–Congo, and the lexical similarities being due to loans.

Common features[edit]

Phonology[edit]

Niger–Congo languages have a clear preference for open syllables of the type CV (Consonant Vowel). The typical word structure of Proto-Niger–Congo (though it has not been reconstructed) is thought to have been CVCV, a structure still attested in, for example, Bantu, Mande and Ijoid – in many other branches this structure has been reduced through phonological change. Verbs are composed of a root followed by one or more extensional suffixes. Nouns consist of a root originally preceded by a noun class prefix of (C)V- shape which is often eroded by phonological change.

Consonants[edit]

Several branches of Niger–Congo have a regular phonological contrast between two classes of consonants. Pending more clarity as to the precise nature of this contrast, it is commonly characterized as a contrast between fortis and lenis consonants.

Vowels[edit]

Many Niger–Congo languages' vowel harmony is based on the [ATR] (advanced tongue root) feature. In this type of vowel harmony, the position of the root of the tongue in regards to backness is the phonetic basis for the distinction between two harmonizing sets of vowels. In its fullest form, this type involves two classes, each of five vowels:

| [+ATR] | [−ATR] |

|---|---|

| [i] | [ɪ][29] |

| [e] | [ɛ][29] |

| [ə] | [a][29] |

| [o] | [ɔ][29] |

| [u] | [ʊ][29] |

The roots are then divided into [+ATR] and [−ATR] categories. This feature is lexically assigned to the roots because there is no determiner within a normal root that causes the [ATR] value.[30]

There are two types of [ATR] vowel harmony controllers in Niger–Congo. The first controller is the root. When a root contains a [+ATR] or [−ATR] vowel, then that value is applied to the rest of the word, which involves crossing morpheme boundaries.[31] For example, suffixes in Wolof assimilate to the [ATR] value of the root to which they attach. Some examples of these suffixes that alternate depending on the root are:

| [+ATR] | [−ATR] | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| -le | -lɛ | 'participant' [30] |

| -o | -ɔ | 'nominalizing' [30] |

| -əl | -al | 'benefactive' [30] |

Furthermore, the directionality of assimilation in [ATR] root-controlled vowel harmony need not be specified. The root features [+ATR] and [−ATR] spread left and/or right as needed, so that no vowel would lack a specification and be ill-formed.[32]

Unlike in the root-controlled harmony system, where the two [ATR] values behave symmetrically, a large number of Niger–Congo languages exhibit a pattern where the [+ATR] value is more active or dominant than the [−ATR] value.[33] This results in the second vowel harmony controller being the [+ATR] value. If there is even one vowel that is [+ATR] in the whole word, then the rest of the vowels harmonize with that feature. However, if there is no vowel that is [+ATR], the vowels appear in their underlying form.[31] This form of vowel harmony control is best exhibited in West African languages. For example, in Nawuri, the diminutive suffix /-bi/ will cause the underlying [−ATR] vowels in a word to become phonetically [+ATR].[33]

There are two types of vowels which affect the harmony process. These are known as neutral or opaque vowels. Neutral vowels do not harmonize to the [ATR] value of the word, and instead maintain their own [ATR] value. The vowels that follow them, however, will receive the [ATR] value of the root. Opaque vowels maintain their own [ATR] value as well, but they affect the harmony process behind them. All of the vowels following an opaque vowel will harmonize with the [ATR] value of the opaque vowel instead of the [ATR] vowel of the root.[30]

The vowel inventory listed above is a ten-vowel language. This is a language in which all of the vowels of the language participate in the harmony system, producing five harmonic pairs. Vowel inventories of this type are still found in some branches of Niger-Congo, for example in the Ghana Togo Mountain languages.[34] However, this is the rarer inventory as oftentimes there are one or more vowels that are not part of a harmonic pair. This has resulted in seven-and nine-vowel systems being the more popular systems. The majority of languages with [ATR] controlled vowel harmony have either seven- or nine-vowel phonemes, with the most common non-participatory vowel being /a/.[29] It has been asserted that this is because vowel quality differences in the mid-central region where /ə/, the counterpart of /a/, is found, are difficult to perceive. Another possible reason for the non-participatory status of /a/ is that there is articulatory difficulty in advancing the tongue root when the tongue body is low in order to produce a low [+ATR] vowel.[35] Therefore, the vowel inventory for nine-vowel languages is generally:

| [+ATR] | [−ATR] |

|---|---|

| [i] | [ɪ] |

| [e] | [ɛ] |

| [a] | |

| [o] | [ɔ] |

| [u] | [ʊ] |

And seven-vowel languages have one of two inventories:

| [+ATR] | [−ATR] |

|---|---|

| [i] | [ɪ] |

| [ɛ] | |

| [a] | |

| [ɔ] | |

| [u] | [ʊ] |

| [+ATR] | [−ATR] |

|---|---|

| [i] | |

| [e] | [ɛ] |

| [a] | |

| [o] | [ɔ] |

| [u] |

Note that in the nine-vowel language, the missing vowel is, in fact, [ə], [a]'s counterpart, as would be expected.[36]

The fact that ten vowels have been reconstructed for proto-Ijoid has led to the hypothesis that the original vowel inventory of Niger–Congo was a full ten-vowel system.[37] On the other hand, Stewart, in recent comparative work, reconstructs a seven-vowel system for his proto-Potou-Akanic-Bantu.[38]

Nasality[edit]

Several scholars have documented a contrast between oral and nasal vowels in Niger–Congo.[39] In his reconstruction of proto-Volta–Congo, Steward (1976) postulates that nasal consonants have originated under the influence of nasal vowels; this hypothesis is supported by the fact that there are several Niger–Congo languages that have been analysed as lacking nasal consonants altogether. Languages like this have nasal vowels accompanied with complementary distribution between oral and nasal consonants before oral and nasal vowels. Subsequent loss of the nasal/oral contrast in vowels may result in nasal consonants becoming part of the phoneme inventory. In all cases reported to date, the bilabial /m/ is the first nasal consonant to be phonologized. Niger–Congo thus invalidates two common assumptions about nasals:[40] that all languages have at least one primary nasal consonant, and that if a language has only one primary nasal consonant it is /n/.

Niger–Congo languages commonly show fewer nasalized than oral vowels. Kasem, a language with a ten-vowel system employing ATR vowel harmony, has seven nasalized vowels. Similarly, Yoruba has seven oral vowels and only five nasal ones. However, the recently discovered language of Zialo has nasal equivalent for each of its seven vowels.

Tone[edit]

The large majority of present-day Niger–Congo languages are tonal. A typical Niger–Congo tone system involves two or three contrastive level tones. Four level systems are less widespread, and five level systems are rare. Only a few Niger–Congo languages are non-tonal; Swahili is perhaps the best known, but within the Atlantic branch some others are found. Proto-Niger–Congo is thought to have been a tone language with two contrastive levels. Synchronic and comparative-historical studies of tone systems show that such a basic system can easily develop more tonal contrasts under the influence of depressor consonants or through the introduction of a downstep.[citation needed] Languages which have more tonal levels tend to use tone more for lexical and less for grammatical contrasts.

| H, L | Dyula–Bambara, Maninka, Temne, Dogon, Dagbani, Gbaya, Efik, Lingala |

| H, M, L | Yakuba, Nafaanra, Kasem, Banda, Yoruba, Jukun, Dangme, Yukuben, Akan, Anyi, Ewe, Igbo |

| T, H, M, L | Gban, Wobe, Munzombo, Igede, Mambila, Fon |

| T, H, M, L, B | Ashuku (Benue–Congo), Dan-Santa (Mande) |

| PA/S | Mandinka (Senegambia), Fula, Wolof, Kimwani |

| none | Swahili |

Abbreviations used: T top, H high, M mid, L low, B bottom, PA/S pitch-accent or stress Adapted from Williamson 1989:27 | |

Morphosyntax[edit]

Noun classification[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Niger–Congo languages are known for their system of noun classification, traces of which can be found in every branch of the family but Mande, Ijoid, Dogon, and the Katla and Rashad branches of Kordofanian. These noun-classification systems are somewhat analogous to grammatical gender in other languages, but there are often a fairly large number of classes (often 10 or more), and the classes may be male human/female human/animate/inanimate, or even completely gender-unrelated categories such as places, plants, abstracts, and groups of objects. For example, in Bantu, the Swahili language is called Kiswahili, while the Swahili people are Waswahili. Likewise, in Ubangian, the Zande language is called Pazande, while the Zande people are called Azande.

In the Bantu languages, where noun classification is particularly elaborate, it typically appears as prefixes, with verbs and adjectives marked according to the class of the noun they refer to. For example, in Swahili, watu wazuri wataenda is 'good (zuri) people (tu) will go (ta-enda)'.

Verbal extensions[edit]

The same Atlantic–Congo languages which have noun classes also have a set of verb applicatives and other verbal extensions, such as the reciprocal suffix -na (Swahili penda 'to love', pendana 'to love each other'; also applicative pendea 'to love for' and causative pendeza 'to please').

Word order[edit]

A subject–verb–object word order is quite widespread among today's Niger–Congo languages, but SOV is found in branches as divergent as Mande, Ijoid and Dogon. As a result, there has been quite some debate as to the basic word order of Niger–Congo.

Whereas Claudi (1993) argues for SVO on the basis of existing SVO > SOV grammaticalization paths, Gensler (1997) points out that the notion of 'basic word order' is problematic as it excludes structures with, for example, auxiliaries.

However, the structure SC-OC-VbStem (Subject concord, Object concord, Verb stem) found in the "verbal complex" of the SVO Bantu languages suggests an earlier SOV pattern (where the subject and object were at least represented by pronouns).

Noun phrases in most Niger–Congo languages are characteristically noun-initial, with adjectives, numerals, demonstratives and genitives all coming after the noun. The major exceptions are found in the western[41] areas where verb-final word order predominates and genitives precede nouns, though other modifiers still come afterwards. Degree words almost always follow adjectives, and except in verb-final languages adpositions are prepositional.

The verb-final languages of the Mende region have two quite unusual word order characteristics. Although verbs follow their direct objects, oblique adpositional phrases (like "in the house", "with timber") typically come after the verb,[41] creating a SOVX word order. Also noteworthy in these languages is the prevalence of internally headed and correlative relative clauses, in both of which the head occurs inside the relative clause rather than the main clause.

Notes[edit]

This article has an unclear citation style. (March 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

^ Irene Thompson, “Niger-Congo Language Family”, ”aboutworldlanguages”, March 2015

^ Heine, Bernd; Nurse, Derek (2000-08-03). African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780521666299..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Ammon, Ulrich (2006). Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Walter de Gruyter. p. 2036. ISBN 9783110184181.

^ Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2018. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twenty-first edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

^ “Niger-Congo Languages”, ”The Language Gulper”, March 2015

^ Irene Thompson, “Niger-Congo Language Family”, ”aboutworldlanguages”, March 2015

^ Katie Manning, The demographic response to Holocene climate change in the Sahara (2014), The demographic response to Holocene climate change in the Sahara

^ Igor Kopytoff, The African Frontier: The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies (1989), 9–10 (cited afer Igbo Language Roots and (Pre)-History, A Mighty Tree, 2011).

^ ab Blench, Roger, THE BENUE-CONGO LANGUAGES: A PROPOSED INTERNAL CLASSIFICATION WORKING DOCUMENT: NOT A DRAFT PAPER NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION this printout: Cambridge, 24 June, 2004.[unreliable source?]

"No comprehensive reconstruction has yet been done for the phylum as a whole, and it is sometimes suggested (e.g. by Dixon 1997) that Niger-Congo is merely a typological and not a genetic unity. This view is not held by any specialists in the phylum, and reasons for thinking Niger-Congo is a true genetic unity will be given in this chapter. It is, however, true that the subclassification of the phylum has been continuously modified in recent years and cannot be presented as an agreed scheme. The factors which have delayed reconstruction are the large number of languages, the inaccessibility of much of the data, and the paucity of able researchers committed to this field. Emphasis will be placed on three characteristics of Niger-Congo; noun-class systems, verbal extensions, and basic lexicon."

See also: Bendor-Samuel, J. ed. 1989. The Niger–Congo Languages. Lanham: University Press of America.

^ Westermann, D. 1922a. Die Sprache der Guang. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

^ Greenberg, J.H. 1964. Historical inferences from linguistic research in sub-Saharan Africa. Boston University Papers in African History, 1:1–15.

^ Blench, Roger, Unpublished Working Draft http://www.rogerblench.info/Language/Niger-Congo/BC/General/Benue-Congo%20classification%20latest.pdf

^ Herman Bell. 1995. The Nuba Mountains: Who Spoke What in 1976?. (The published results from a major project of the Institute of African and Asian Studies: the Language Survey of the Nuba Mountains.)

^ Williamson, K. 1971. The Benue–Congo languages and Ijo. Current Trends in Linguistics, 7. ed. T. Sebeok 245–306. The Hague: Mouton.

^ Williamson, K. 1988. Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of the Niger Delta. The early history of the Niger Delta, edited by E.J. Alagoa, F.N. Anozie and N. Nzewunwa. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

^ Williamson, K. 1989. Benue–Congo Overview. In The Niger–Congo Languages. J. Bendor-Samuel ed. Lanham: University Press of America.

^ De Wolf, P. 1971. The noun class system of Proto-Benue–Congo. The Hague: Mouton.

^ Blench, R.M. 1989. A proposed new classification of Benue–Congo languages. Afrikanische Arbeitspapiere,

Köln, 17:115–147.

^ Williamson, Kay & Blench, Roger (2000) 'Niger–Congo', in Heine, Bernd & Nurse, Derek (eds.) African languages: an introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

^ Gerrit Dimmendaal (2008) "Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent", Language and Linguistics Compass 2/5:841.

^ Martin H. Steinberg, Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 717.

^ "Niger-Congo: an alternative view" (PDF). Rogerblench.info. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

"Roger Blench: Niger-Congo reconstruction". Rogerblench.info. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

^ Hans G. Mukarovsky, A Study of Western Nigritic, 2 vols. (1976–1977). Blench (2004): "Almost simultaneously [with Greenberg (1963)], Mukarovsky (1976-7) published his analysis of 'Western Nigritic'. Mukarovsky's basic theme was the relationship between the reconstructions of Bantu of Guthrie and other writers and the languages of West Africa. Mukarovsky excluded Kordofanian, Mande, Ijo, Dogon, Adamawa-Ubangian and most Bantoid languages for unknown reasons, thus reconstructing an idiosyncratic grouping. Nonetheless, he buttressed his argument with an extremely valuable compilation of data, establishing the case for Bantu/Niger-Congo genetic link beyond reasonable doubt."

^ Williamson, Kay; Blench, Roger (2000). "Niger-Congo". In Bernd Heine; Derek Nurse. African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–12.

^ http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199935345-e-3

^ Rebecca Grollemund, Simon Branford, Jean-Marie Hombert & Mark Pagel. 2016. Genetic unity of the Niger-Congo family. Towards Proto-Niger-Congo: comparison and reconstruction (2nd International Congress)

^ Tom Gueldemann (2018) Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa, p. 146.

^ Pozdniakov, Konstantin (2018). The numeral system of Proto-Niger-Congo: A step-by-step reconstruction (pdf). Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1311704. ISBN 978-3-96110-098-9.

^ abcdef Morton, Deborah. [ATR] Harmony in an Eleven Vowel Language. Ohio State University, 2012:70–71.

^ abcde Unseth, Carla. Vowel Harmony in Wolof Archived 2013-09-03 at the Wayback Machine.. Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, 2009:2–3.

^ ab Bakovic, Eric. Harmony, Dominance and Control. Diss. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 2000:ii.

^ "Clements, G. N. 1981. Akan vowel harmony: A non-linear analysis. Harvard Studies in

Phonology 2.108–177."

^ ab Casali, Roderic F. "Nawuri ATR Harmony in Typological Perspective." Archived 2014-03-30 at the Wayback Machine. Summer Institute of Linguistics, 2002:29. Journal of West African Languages 29.1 (2002).

^ "Anderson, C.G. 1999. ATR vowel harmony in Akposso. Studies in African Linguistics, 28(2):185–214."

^ "Archangeli, Diana, & Douglas Pulleyblank. 1994. Grounded Phonology (Current Studies in Linguistics, 25.) Cambridge: MIT Press."

^ Casali, Roderic F. "ATR Harmony in African Languages." Language and Linguistics Compass 2.3 (2008): 469–549.

^ Doneux, Jean L. 1975. Hypothèses pour la comparative des langues atlantiques. Africana Linguistica 6.41–129.

Tervuren: Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale. (Re: proto-Atlantic), Williamson, Kay. 2000. Towards reconstructing Proto-Niger-Congo. Proceedings of the 2nd World

Congress of African Linguistics, Leipzig 1997, ed. H. E. Wolff and O. Gensler, 49–70. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe. (Re: proto-Ijoid), Stewart, John M. Towards Volta-Congo Reconstruction: Rede. Leiden: Universitaire Pers Leiden, 1976., Casali, Roderic F. "On the Reduction of Vowel Systems in Volta-Congo." African Languages and Cultures 8.2 (1995: 109–121) (Re: proto-Volta-Conga)

^ Stewart, John M., 2002. The potential of Proto-Potou-Akanic-Bantu as a pilot Proto-Niger- Congo, and the reconstructions updated. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 23: 197–224.

^ le Saout (1973) for an early overview, Stewart (1976) for a diachronic, Volta–Congo wide analysis, Capo (1981) for a synchronic analysis of nasality in Gbe (see Gbe languages: nasality), and Bole-Richard (1984, 1985) as cited in Williamson (1989) for similar reports on several Mande, Gur, Kru, Kwa, and Ubangi languages.)

^ As noted by Williamson (1989:24). The assumptions are from Ferguson's (1963) 'Assumptions about nasals' in Greenberg (ed.) Universals of Language, pp 50–60 as cited in Williamson art.cit.

^ ab Haspelmath, Martin; Dryer, Matthew S.; Gil, David and Comrie, Bernard (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures; pp 346–385. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

ISBN 0-19-925591-1

Further reading[edit]

- Vic Webb (2001) African Voices: An Introduction to the Languages and Linguistics of Africa

Bendor-Samuel, John & Rhonda L. Hartell (eds.) (1989) The Niger–Congo Languages – A classification and description of Africa's largest language family. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.- Bennett, Patrick R. & Sterk, Jan P. (1977) 'South Central Niger–Congo: A reclassification'. Studies in African Linguistics, 8, 241–273.

- Blench, Roger (1995) 'Is Niger–Congo simply a branch of Nilo-Saharan?'[1] In Proceedings: Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 1992, ed. R. Nicolai and F. Rottland, 83–130. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- —— (2011) "Can Sino-Tibetan and Austroasiatic help us understand the evolution of Niger–Congo noun classes?",[2] CALL 41, Leiden

- —— (2011) "Should Kordofanian be split up?"[3], Nuba Hills Conference, Leiden

- Capo, Hounkpati B.C. (1981) 'Nasality in Gbe: A Synchronic Interpretation' Studies in African Linguistics, 12, 1, 1–43.

- Casali, Roderic F. (1995) 'On the Reduction of Vowel Systems in Volta–Congo', African Languages and Cultures, 8, 2, December, 109–121.

Dimmendaal, Gerrit (2008). "Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent". Language and Linguistics Compass. 2 (5): 840–858. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00085.x.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1963) The Languages of Africa. Indiana University Press.

- Gregersen, Edgar A. (1972) 'Kongo-Saharan'. Journal of African Languages, 4, 46–56.

- Nurse, D., Rose, S. & Hewson, J. (2016) Tense and Aspect in Niger-Congo, Documents on Social Sciences and Humanities, Royal Museum for Central Africa

- Olson, Kenneth S. (2006) 'On Niger–Congo classification'. In The Bill question, ed. H. Aronson, D. Dyer, V. Friedman, D. Hristova and J. Sadock, 153–190. Bloomington, IN: Slavica.

- Saout, J. le (1973) 'Languages sans consonnes nasales', Annales de l Université d'Abidjan, H, 6, 1, 179–205.

- Stewart, John M. (1976) Towards Volta–Congo reconstruction: a comparative study of some languages of Black-Africa. (Inaugural speech, Leiden University) Leiden: Universitaire Pers Leiden.

- Stewart, John M. (2002) 'The potential of Proto-Potou-Akanic-Bantu as a pilot Proto-Niger–Congo, and the reconstructions updated', in Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 23, 197–224.

- Williamson, Kay (1989) 'Niger–Congo overview', in Bendor-Samuel & Hartell (eds.) The Niger–Congo Languages, 3–45.

- Williamson, Kay & Blench, Roger (2000) 'Niger–Congo', in Heine, Bernd and Nurse, Derek (eds) African Languages – An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–42.

External links[edit]

An Evaluation of Niger–Congo Classification, Kenneth Olson

Tense and Aspect in Niger-Congo, Derek Nurse, Sarah Rose & John Hewson

Categories:

- Niger–Congo languages

- Proposed language families

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.856","walltime":"1.110","ppvisitednodes":{"value":2644,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":100631,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":2384,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":13,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":10,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":42946,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":2,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 786.918 1 -total"," 51.55% 405.645 1 Template:Reflist"," 28.72% 226.005 4 Template:Cite_book"," 9.71% 76.406 1 Template:Infobox_language_family"," 9.38% 73.808 2 Template:Fix"," 8.21% 64.642 1 Template:ISBN"," 8.00% 62.976 1 Template:Authority_control"," 7.86% 61.835 1 Template:Citation_needed"," 7.48% 58.854 1 Template:Infobox"," 5.12% 40.317 8 Template:Navbox"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.339","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":5458574,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1245","timestamp":"20181223150028","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":112,"wgHostname":"mw1332"});});