Indiana Territory

| Territory of Indiana | |||||

Organized incorporated territory of the United States | |||||

| |||||

Flag Flag | |||||

| |||||

Capital | Vincennes (1800–1813) Corydon (1813–1816) | ||||

Government | Organized incorporated territory | ||||

Governor | |||||

| • | 1800–1812 | William Henry Harrison | |||

| • | 1812–1813 | John Gibson (acting) | |||

| • | 1813–1816 | Thomas Posey | |||

Secretary | |||||

| • | 1800–1816 | John Gibson | |||

History | |||||

| • | Established | July 4, 1800 | |||

| • | Treaty of Grouseland signed | March 1805 | |||

| • | Michigan Territory created | June 30, 1805 | |||

| • | Representation in Congress | December 12, 1805 | |||

| • | Illinois Territory created - Treaty of Fort Wayne - Legislature popularly elected - Tecumseh's War - War of 1812 - Constitution drafted & adopted | March 1, 1809 September 30, 1809 November 1809 1811–1812 1812–1814 June 1816 | |||

| • | Granted Statehood | December 11, 1816 | |||

Population | |||||

| • | 1800 | 2,632 | |||

| • | 1810 | 24,520 | |||

| • | 1816 | 63,897 | |||

The Indiana Territory was created by a congressional act that President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, to December 11, 1816, when the remaining southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana.[1] The territory originally contained approximately 259,824 square miles (672,940 km2) of land, but its size was decreased when it was subdivided to create the Michigan Territory (1805) and the Illinois Territory (1809). The Indiana Territory was the first new territory created from lands of the Northwest Territory, which had been organized under the termos of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

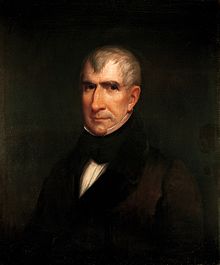

William Henry Harrison, the territory's first governor, oversaw treaty negotiation with the native inhabitants that ceded tribal lands to the U.S. government, opening large parts of the territory to further settlement. In 1809 the U.S. Congress established a bicameral legislative body for the territory that included a popularly-elected House of Representatives and a Legislative Council. In addition, the territorial government began planning for a basic transportation network and education system, but efforts to attain statehood for the territory were delayed due to war. At the outbreak of Tecumseh's War, when the territory was on the front line of battle, Harrison led a military force in the opening hostilities at the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811) and in the subsequent invasion of Canada during the War of 1812. After Harrison resigned at the territorial governorn, Thomas Posey was appointed to the vacant governorship, but the opposition party, led by Congressman Jonathan Jennings, dominated the territorial affairs in its final and began pressing for statehood.

In June 1816 a constitutional convention was held at Corydon, where a state constitution was adopted on June 29, 1816. General elections were held in August to fill offices for the new state government, the new officeholders were sworn into office in November, and the territory was dissolved. On December 11, 1816, President James Madison signed the congressional act that formally admitted Indiana to the Union as the nineteenth state.

Contents

1 Geographical boundaries

2 Government

2.1 Governors

2.2 Judicial court

2.3 Legislature

2.4 Congressional delegation

2.5 Other high officials

2.6 Territorial finances

3 Political issues

3.1 Slavery

3.2 Relocating the seat of government

4 History

4.1 Naming the new territory

4.2 Western expansion and conflict

4.3 Territory formation

4.4 District of Louisiana

4.5 Tecumseh's War

4.6 War of 1812

4.7 Movement toward statehood

4.8 Achieving statehood

5 Commemoration

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Geographical boundaries

When the Indiana Territory was formed in 1800 its original boundaries included the western portion the Northwest Territory. This encompassed an area northwest of a line beginning at the Ohio River, on the bank opposite to the mouth of the Kentucky River, extending northeast to Fort Recovery, in present-day western Ohio, and north to the border between the United States and Canada along a line approximately 84 degrees 45 minnutes West longitude.[2][3][4]

The territory initially included most of the present-day state of Indiana, all of present-day states of Illinois and Wisconsin, fragments of present-day Minnesota that were east of the Mississippi River, nearly all of the Upper Peninsula the western half of the Lower Peninsula of present-day Michigan, and a narrow strip of land in present-day Ohio that was northwest of Fort Recovery.[3][5] This latter parcel became part of Ohio when it attained statehood in 1803. The Indiana Territory's southeast boundary was shifted in 1803, when Ohio became a state, to the mouth of the Great Miami River from its former location opposite the mouth of the Kentucky River. In addition, the eastern part of present-day Michigan was added to the Indiana Territory. The territory's geographical area was further reduced in 1805 with the creation of the Michigan Territory to the north, and in 1809, when the Illinois Territory was established to the west.[6]

Government

The Indiana Territory's government passed through a non-representative phase from 1800 to 1804; a semi-legislative second phase, which included the election of lower house of the territorial legislature, that extended through the ongoing hostilities with Native Americans and the War of 1812; and a final period, when the territory's population increased and its residents successfully petitioned Congress for statehood in 1816.[7]

Under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance, during the non-representative phase of territorial government the U.S. Congress, and after 1789, the president with congressional approval, appointed a governor, secretary, and three judges to govern each new territory. Local inhabitants did not elect these territorial officials. During the second, or semi-legislative phase of government, the territory's adult males who owned at least fifty acres of land to elect representatives to the lower house of the territorial legislature. In addition, the Congress, and later, the president with congressional approval, appointed five adult males who owned at least five hundred acres of land to the upper house of the territorial legislature from a list of ten candidates that the lower house submitted for consideration. In the semi-legislative phase of government, the upper and lower houses could legislate for the territory, but the territorial governor retained absolute veto power. When the territory reached a population of 60,000 free inhabitants, it entered the final phase that included its successful petition to Congress for statehood.[8][9]

In 1803, when the Indiana Territory was formed from the remaining Northwest Territory after Ohio attained statehood, the requirement for proceeding to the second or semi-legislative phase of territorial government was modified. Instead of requiring the territory's population to reach 5,000 free adult males, the second phase could be initiated when the majority of territory's free landholders informed the territorial governor that they wanted to do so.[10] In 1810 the requirement for voters to be landholders was replaced with a law granting voting rights to all free adult males who paid county or territorial taxes and had resided in the territory for a least a year.[11]

Governors

Because of William Henry Harrison's leadership in securing passage of the Land Act of 1800 and his help in forming the Indiana Territory in 1800, while serving as the Northwest Territory's delegate to the U.S. Congress, it was not surprising that President John Adams chose him to become the first governor of the territory. Presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison made a total of three appointments to the office of governor of the Indiana Territory between July 4, 1800, when the territory was officially established, and November 7, 1816, when Jonathan Jennings was sworn in as the first governor of the state of Indiana.[12][10]

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Appointed by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | William Henry Harrison | May 13, 1800 (appointed);[7] January 10, 1801 (took office)[13] | December 28, 1812 (resigned)[14] | John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison |

| 2 | John Gibson | December 28, 1812 (appointed)[15] Acting governor: July 4, 1800 – January 10, 1801; June 1812–May 1813[16] | March 3, 1813[15] | James Madison |

| 3 | Thomas Posey | March 3, 1813 (appointed); May 1813 (took office)[15] | November 7, 1816[17] | James Madison |

Judicial court

When the Indiana Territory was created in 1800, the Ordinance of 1787 made no provision for a popularly-elected territorial government in the non-representative phase of territorial government (1800 to 1804).[18] Instead of separate legislative and judicial branches of the territorial government, the U.S. Congress, and later, the president with congressional approval, had the authority to appoint a General Court, consisting of three territorial judges. The judges were initially appointed by the president, who later delegated this authority to the territorial governor. President Adams chose William Clarke, Henry Vanderburgh, and John Griffin as the territory's first three judges. Following Clarke's death in November 1802, Thomas T. Davis was appointed as his replacement.[19]

Acting as the combined judicial and legislative government, the territorial governor and the three judges adopted the laws to govern the territory. In addition to working with the territorial governor on legislative issues, the territorial judges presided over the General Court. When the Indiana Territory entered the second or semi-legislative phase of government in 1805, the legislature gradually became the dominant branch and the judges focused on judicial matters.[19][20] In 1814, as the territory progressed toward statehood, three circuit courts were established. Governor Posey appointed Isaac Blackford, Jesse Lynch Holman, and Elijah Sparks as presiding judges over the circuit courts. James Noble was appointed to replace Sparks following Sparks' death in early 1815.[21]

Legislature

A map of the Indiana Territory in 1812 displaying notable places and battles in the War of 1812

When the Indiana Territory entered its second or semi-legislative phase of government in 1805,

territorial inhabitants were allowed to elect representatives to the lower house of its bicameral legislature. President Jefferson delegated the task of choosing the five members of the Legislative Council (upper house of the legislature) to the governor, who chose from a list of ten candidates provided by the lower house.[22][23]

After the formation of the new legislative body, each county in the territory was granted the right to elect representatives to the House of Representatives (the legislative assembly's lower house). The lower house initially included seven representatives, one from Dearborn County, one from Clark County, two from Knox County, two from St. Clair County, and one from Randolph County.[22][23] The territorial legislature met for the first time on July 29, 1805.[24] Harrison, the territorial governor, retained his veto powers, as well as his general executive and appointive authority, while the legislative assembly had the authority to pass laws, subject to the governor's approved before they could be enacted. The change in territorial governance also removed the terrorial judges' legislative powers, leaving the territorial court with only its judicial authority.[22][23]

In 1809, after the Indiana Territory was divided to create the Illinois Territory, the U.S. Congress altered the makeup of the territorial legislature. The members of the House of Representatives continued to be elected by the territorial inhabitants, and apportioned in relation to each county's population, but membership in the five-member upper house (Legislative Council) was also by popular vote and apportioned among the territory's counties. Harrison County, established in 1808 from portions of Knox and Clark counties, elected one representative to the lower house; Clark and Dearborn counties each had two representatives; and the more populated Knox County had three. In Harrison, Clark, and Dearborn counties the voters in each county elected one legislative councilor to the upper house, while Knox County elected two members.[25][26] This bicameral legislative structure remained unchanged for the remainder of the territory's existence.

Congressional delegation

Territorial delegates to the U.S. House of Representatives could attend congressional sessions with the right to debate, submit legislation, and serve on committees, but was not permitted to vote on legislation.[27] When the Indiana Territory entered its second phase of governance in 1805, the territory's legislative assembly elected Benjamin Parke as its delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. Jesse B. Thomas was appointed to the post following Parke's resignation in 1808.[28] Congress approved a law in 1809 that allowed the territory's inhabitants to chose a delegate to Congress in a territory-wide election.[29]Jonathan Jennings defeated Thomas Randolph, the territory's attorney general and Harrison's chosen candidate, in a highly-contested race to become the territory's first popularly-elected representative to the U.S. Congress. Jennings was reelected to the post in 1811, 1812, and 1814, prior to his election as the first governor of Indiana in 1816.[30][31]

| Delegate | Years | Party |

|---|---|---|

Benjamin Parke | December 12, 1805 – March 1, 1808 | none |

Jesse Burgess Thomas | October 22, 1808 – March 3, 1809 | Democratic-Republican |

Jonathan Jennings | November 27, 1809 – December 11, 1816 | none |

Other high officials

In addition to the territorial governor and three judges, the office of secretary was established in 1800, when the Indiana Territory was initially formed. Governor Harrison appointed a treasurer and attorney general in 1801 as the only additional government officials during the territory's non-representative phase of government.[32] During the second, or semi-representational phase, which Governor Harrison announced in December 1804, the offices of secretary, treasurer and attorney general continued; however, the office of territorial auditor continued only until 1814, when it was combined with the office of territorial treasurer. The territory also had chancellor during most of this period.[33]

Secretary

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Party | Hometown | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Gibson | July 4, 1800 | November 7, 1816 | Democratic-Republican | Knox County, Indiana | Gibson also served as acting governor of the Indiana Territory (July 4, 1800 – January 10, 1801, and June 1812–May 1813) and officially as territorial governor (December 28, 1812 – March 3, 1813)[34] |

Auditor

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Hometown | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | William Prince | 1810 | 1813 | Vincennes, Indiana | [35] |

| 2 | Davis Floyd | 1813 | 1814 | Corydon, Indiana |

Treasurer

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Hometown | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | General Washington Johnston | 1813 | 1814 | Vincennes, Indiana | |

| 2 | Davis Floyd | 1814 | 1816 | Corydon, Indiana |

Attorney General

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Hometown | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benjamin Parke | 1804 | 1808 | Knox County, Indiana | |

| 2 | John Rice Jones | 1808 | 1816 | Clark County, Indiana |

Territorial finances

During the first or non-legislative phase of government, the federal government paid the salaries of the governor, the three-member judicial council, and the territorial secretary, which cost about $5,500 per year. In addition, a small fund of approximately $200 covered other expenses such as printing, postage, and rent. The federal government did not provide funds for any additional governmental offices such as the treasurer and attorney general. Salaries for these officials were paid from the territory's treasury. When the Indiana Territory reached the second or semi-legislative phase of government, the federal government paid the salaries of the territorial governor, judges, and secretary at a cost of approximately $6,687 per year. The territorial treasury was responsible for funding legislative expenses, as well as the salaries of the treasurer, auditor, attorney general, and chancellor. The territorial treasur also paid operational expenses such as printing, rent, stationery, and other supplies and services. These expenses were estimated to cost $10,000 per year.[36][37]

Revenue for the territory was limited, with the primary source of funds coming from the sale of federal lands. (The territory collected three percent of the proceeds of each sale.[citation needed]) Other revenue came from the collection of duties, licenses, and excise taxes. In 1811 property taxes collected from landowners were based on the numbers of acres and its rating; previously, these taxes were based on land values. Taxes were also collected for territorial counties to use. After 1815 taxes on some types of manufactured goods to provide additional funds for the territorial government.[38] Trading ventures with the Native American tribes provided lesser revenues.[citation needed]

Territorial revenue fell to critical levels due to the War of 1812, when many of the territory's taxpayers were unable to pay what they owed and their land reverted to the federal government. Financial issues also caused the movement for statehood to be delayed until after the war's end. At one point during 1813, for example, the balance in territory's treasury was a meager $2.47. To increase the treasury, tax levies were modified and new forms of revenue were established. These changes included reductions in some taxes, increases in others, and implementing licensing requirements for some types of business ventures in order to stabilize revenue. William Prince, the first territorial auditor, was also blamed for the territory's revenue shortage because he had failed to collect taxes from two territorial counties.[39]

Growth of territory's population helped improve its financial situation through the collection of various taxes, including property taxes and taxes on sale of public lands. However, governmental expenses also increased as new counties and towns were formed, causing the need for new governmental offices and further increases in the government's overall size.[40]

Political issues

William Henry Harrison, the 1st Governor of Indiana Territory from 1801 to 1812, and the 9th President of the United States

The major political issue in Indiana's territorial history was slavery; however, there were others, including Indian affairs, the formation of northern and western territories from portions of the Indiana Territory, concerns about the lack of territorial self-government and representation in Congress, and ongoing criticisms of Harrison's actions at territorial governor.[41][42]

Most of these issues were resolved before Indiana achieved statehood. The formation of the Michigan Territory in 1805 and the Illinois Territory in 1809 ended the debate about the territories geographical size. In the second phase of territorial governance in 1805 the increasing democratization of the government shifted the authority initially placed in the hands of the territorial governor and a judicial council to a legislative branch of elected representatives and a delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. The debate over the issue of allowing slavery in the territory was settled in 1810; however, criticism of Governor Harrison continued, even after much of his authority was transferred to territorial legislators and judges.[41]

Slavery

Congress granted territories the right to legalize slavery within their boundaries if they so chose to do so. In December 1802 delegates from Indiana Territory's four counties passed a resolution in favor of a ten-year suspension of Article Six of the Northwest Ordinance, which prohibited slavery in the original Northwest Territory. They also petitioned Congress for the suspension in order to make the region more appealing to slave-holding settlers and ultimately make the territory economically viable by increasing its population. In addition, the petition requested that the slaves and their children brought into the territory during the suspension period should remain slaves even after the suspension ended. Benjamin Parke, a pro-slavery supporter who became the territory's first representative in Congress in 1805, carried the petition to Washington, D.C.; however, Congress failed to take action, leaving Harrison and the territorial judges to pursue other options.[43][44]

In 1803 Harrison and the General Court judges passed legislation that evaded the Ordinance of 1787 in order permit slavery in the Indiana Territory. The bill authorized legalized indenture, which allowed adult slaves owned or purchased outside the territory to be brought into the territory and bound into service for fixed terms set by the slave owner.[45][44][46] After the territory was granted representation in Congress in 1805, Parke, the territory's delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, was able to get Congress to pass legislation to suspend Article Six for ten years, granting the territories covered under the ordinance the ability to legalize slavery in their territories.[47]

Harrison's attempts to allow slavery in the Indiana Territory caused a significant opposition from the Quakers who had settled in the eastern part of the territory. They responded by forming an anti-slavery party. Davis Floyd of Clark County was the only anti-slavery representative elected to the territory's House of Representatives in the 1805 election, but Harrison's measures to legalize slavery in the territory were blocked by the two representatives from St. Clair County, who refused to authorize slavery unless Harrison supported their request for a separate territory, which Harrison opposed.[48][49]

In 1809, five years after Congress established the Michigan Territory from the northern portion of the Indiana Territory, the St. Clair County settlers successfully petitioned Congress for the formation of a separate territory. Despite Harrison's disapproval, Congress approved the formation of the Illinois Territory from the western portion of the Indiana Territory, in addition to granting the inhabitants of the Indiana Territory the right to elect a delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and members of the territory's Legislative Council (upper house). Harrison, whose political power was reduced by these changes, found himself at odds with the territorial legislature when the anti-slavery party came to power after the 1809 elections. Voters promptly rebuffed many of his plans for slavery, and in 1810 the territorial legislature repealed the indenturing laws that Harrison and the judicial court had enacted in 1803.[50][51]

Relocating the seat of government

The capital of the Indiana Territory remained in Vincennes from 1800 to 1813. when the territorial legislature moved it to Corydon. After the Illinois Territory was formed from the western portion of the Indiana Territory in 1809, Vincennes, which was iniitally situated in the center of the territory, was now on its far west edge. The territorial legislature was also becoming increasingly fearful that the outbreak of the War of 1812 could cause an attack on Vincennes, resulting in their decision to move the seat of government to a location closer to the territory's population center. In addition to Corydon, the towns of Madison, Lawrenceburg, Vevay, and Jeffersonville were considered as potential sites for the new capital. On March 11, 1813, the territorial legislature selected Corydon as the new seat of government for the territory, effective May 1, 1813.[52][53]

Harrison also favored Corydon, a town he had founded, named, and where he owned an estate. In 1813, after it was brought to the territorial legislature’s attention that plans were underway to construct a new county courthouse in Corydon and the new building could also be used for its assemblies (a significant cost savings), the government made is decision to relocate the territorial capital to Corydon. Construction on the new capitol building began in 1814 and was nearly finished bu 1816.[52][53]

History

The area that became the Indiana Territory was once part of the Northwest Territory, which the Congress of the Confederation formed under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance on July 13, 1787. This ordinance outlined the basis for government in the western lands, and also provided for an administrative structure to oversee the territory, including a three-stage process for transitioning from territory to statehood. In addition, the Land Ordinance of 1785 called for the U.S. government to survey the newly-acquired territory for future sale and development. The Northwest Territory, which initially included land bounded by the Appalachian Mountains, and the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio River, was subsequently partitioned into smaller territories that included the Indiana Territory (1800), Michigan Territory (1805), the Illinois Territory (1809), and eventually became the present-day states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and eastern Minnesota.[54]

Naming the new territory

Indiana, meaning "Land of the Indians", references the fact that most of the area north of the Ohio River was still inhabited by Native Americans.

Formal use of the word Indiana dates from 1768, when the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy reserved about 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares) of land in the present-day state of West Virginia and deeded it to a twenty-five-member Philadelphia-based trading company that engaged in trade with the native tribes in the Ohio River valley. The company named their land claim Indiana, in honor of its previous owners. In 1776 the land claim was transferred to the Indiana Land Company and offered for sale; however, the government of Virginia disputed the claim, arguing that it was the rightful owner because the land fell within its boundaries. The United States Supreme Court took up the case and extinguished the company's right to the land in 1798. Two years later, Congress applied the Indiana land company's name to the new territory.[55]

Western expansion and conflict

Passage of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 committed the U.S. government to continued plans for western expansion. Increasing tensions with the Native Americans who occupied the western lands erupted the Northwest Indian War.[56][57] During the fall of 1790, American forces under the command of General Josiah Harmar unsuccessfully pursued the Miami tribe near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana, but had to retreat. In the meantime, Major Jean François Hamtramck led an expedition from Fort Knox to Wea, Potawatomi and Kickapoo villages on the Wabash, Vermilion and Eel Rivers, but lacked sufficient provisions to continue, forcing a return to Vincennes.[58][59]

In 1791 Major General Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, commanded about 2,700 men in a campaign to establish a chain of forts and enforce peace in the area. In the early morning of November 3, 1791, nearly a 1,000 Miamis, Shawnees, Delawares and other warriors under the leadership of Chief Little Turtle launched a surprise attack on the American camp near the Miami town of Kekionga, causing the Americans nearly nine hundred casualties and forcing the militia's retreat. St. Clair's Defeat (1791) remains the U.S. Army's worst defeat by American Indians in history. Casualties included 623 federal soldiers killed and another 258 wounded; the Indian confederacy lost an estimated 100 men.[60][61]

Anthony Wayne concludes peace with the Northwestern Indian Confederacy in the Treaty of Greenville.

In August 1794, General "Mad Anthony" Wayne organized the Legion of the United States and defeated a Native American force at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The battle was a turning point for the Americans, who took control of the area near the strategically important Maumee–Wabash portage, as well as Fort Miamis at Kekionga (rebuilt as Fort Wayne). In addition, several other forts were built in the territory to maintain American control of the area.[61][62]

The Treaty of Greenville (1795) ended the Northwest Indian War and marked the beginning of a series of land cession treaties. Under the terms of this treaty, native tribes ceded southeastern Indiana and two-thirds of present-day Ohio to the U.S. government. As a result of the treay, the Miamis considered themselves allies with the United States and thousands of acres of newly-ceded western lands attracted an increasing number of new settlers to what would become the Indiana Territory.[63][64]

Territory formation

The U.S. Congress passed legislation to form the Indiana Territory on May 7, 1800, effective July 4, 1800. The new territory was established by dividing the Northwest Territory in advance of Ohio's statehood.[65] At the time the Indiana Territory was formed, the two main American settlements in what would later become the state of Indiana were at Vincennes and Clark's Grant, while the settlement at Kaskaskia would later become a part of Illinois. In 1800 the Indiana Territory's total white population was 5,641, but its Native American population was estimated to be near 20,000, possibly as high as 75,000.[66][67]

Grouseland, the home of Governor William Henry Harrison

President John Adams appointed William Henry Harrison as the first governor of the territory on May 13, 1800, but Harrison did not arrive in the territory to begin his duties as governor until January 10, 1801. John Gibson, the territorial secretary, served as acting governor until Harrison's arrival at Vincennes.[12][68][69]

A three-member panel of judges called the General Court assisted the territorial governor. Together they served as both the highest legislative and judicial authority in the territory.[70] As governor of a territory of the first stage, which was outlined in the Northwest Ordinance, Harrison had wide-ranging powers in the new territory that included the authority to appoint all territorial officials and members of the territorial General Assembly. He also had the authority to divide the territory into districts.[71]

Vincennes, the territory's oldest settlement and among its largest with 714 townspeople in 1800, became its first territorial capital. The former French trading post was also one of the few white settlements in the territory.[72][73] Indiana Territory began with four counties: Saint Clair and Randolph County, which became part of present-day Illinois; Knox in present-day Indiana; Wayne County, which became part of present-day Michigan.[74][75] Governor Harrison formed Clark County, the first new county in the territory, out of the eastern portion of Knox County.[76] Additional counties were established as the territory's population increased.[67] By 1810 the Indiana Territory's population reached 24,520, even after the territory's size had been reduced with formation of the Michigan Territory (1805) and Illinois Territory (1809). When the Indiana Territory petitioned for statehood in 1816, its population was spread among fifteen counties and exceeded 60,000 people, which was the minimum required for statehood under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance of 1796.[77]

Because Harrison's political fortunes were tied to Indiana's rise to statehood, he was eager to expand the territory. In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson granted Harrison the authority to negotiate and conclude treaties with the Native American tribes in the territory. Harrison oversaw the establishment of thirteen treaties that ceded more than 60,000,000 acres (24,000,000 hectares) of land from Native American tribes, including most present-day southern Indiana, to the U.S. government.[78]

The Treaty of Vincennes (1803) was the first of several treaties that Harrison negotiated as territorial governor. Leaders from local tribes signed this treaty to recognize Americans' possession of the Vincennes tract, an area that George Rogers Clark had captured from the British during the American Revolutionary War. The Treaty of Grouseland (1805) further secured the federal government's possession of land in present-day south-central Indiana. After the signing of the contentious and disputed Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809), in which Harrison acquired for the U.S. government more than 250,000,000 acres (100,000,000 hectares) of land in what later became central Indiana and eastern Illinois, tensions between the Native American and settlers on the frontier neared the breaking the point.[78][79]

The availability of low-cost federal land led to a rapid increase in the population of the territory, with thousands of new settlers entering the region every year. Large settlements began to spring up on the periphery of the territory around the Great Lakes, the Ohio River, the Wabash River, and the Mississippi River. Much of the interior, though, remained inhabited by the Native American tribes and was left unsettled.[78]

District of Louisiana

While Native Americans continued to cede large tracts of land in the Indiana Territory to the federal government, the Americans also expanded their ownership of lands farther west as a result of the Louisiana Purchase agreement with France. From October 1, 1804, until July 4, 1805, administrative powers of the [D]istrict of Louisiana were extended to the governor and judges of the Indiana Territory as a temporary measure to establish a civil government for the newly purchased lands. The district encompassed all of the Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 33rd parallel, which serves as the present-day border between the states of Arkansas and Louisiana.[80][81]

Under the terms of the act establishing the district's temporary government, Governor Hrrison and the Indiana Territory's judges enacted laws that extended to the Louisiana district.[80] Local residents, who had previously lived under France's civil law, objected to many of the provisions of the U.S. government, including their imposition of common law.[82] The Indiana Territory's temporary administration of the district of Louisiana lasted only nine months, until the Territory of Louisiana was established, effective July 4, 1805, with its own territorial government.[83]

One of the most notable events during the Indiana Territory's administration of the district of Louisiana was the Treaty of St. Louis in which the Sac and Fox tribes ceded northeastern Missouri, northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin to the United States. Resentments over this treaty later caused the native tribes to side with the British during the War of 1812 in raids along the Missouri, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers, and lead to their involvement in the Black Hawk War in 1832.[84]

Tecumseh's War

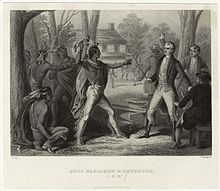

At Vincennes in 1810, Tecumseh loses his temper when William Henry Harrison refuses to rescind the Treaty of Fort Wayne.

Ongoing tensions between the Native Americans and new settlers led to further hostilities between American forces and a pan-Indian confederacy.[85] A resistance movement against U.S. expansion that developed around two Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (The Prophet), became known as Tecumseh's War. Tenskwatawa convinced member of native tribes that the Great Spirit would protected them from harm if they would rise up against the whites. He further encouraged resistance by telling the tribes to only pay white traders half of what they owed, and to give up all the white man's ways, including their clothing, whiskey, and guns.[86]

In 1810 Tecumseh and an estimated 400 armed warriors traveled to Vincennes, where he confronted Harrison and demanded that the governor rescind the Treaty of Fort Wayne. Harrison refused and the war party left peacefully, but Tecumseh was angry and threatened retaliation. Afterwards, Tecumseh journeyed south to meet with representatives of the tribes in the region, hoping to create a confederation of warriors to battle the Americans.[87]

In 1811, while Tecumseh was still away, U.S. Secretary of War William Eustis authorized Harrison to march against the nascent confederation as a show of force. Harrison moved north with an army of more than 1,000 men in an attempt to intimidate the Shawnee into making peace. Early on the morning of November 6, tribal warriors launched a surprise attack on Harrison's army. The ensuing battle became known as the Battle of Tippecanoe, where Harrison ultimately won his famous victory on November 7 at Prophetstown, along the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers. Harrison was publicly hailed as a national hero and the nickname of "Old Tippecanoe," despite the fact that his troops had greatly outnumbered the Indian forces and had suffered many more casualties.[88][89] Aftr the battle, central Indiana was opened to further settlement by allowing more settlers to safely venture beyond the southern periphery of the territory.[90]

War of 1812

Tecumseh's war with the Americans merged with the War of 1812 after the pan-Indian Confederation allied with the British in Canada. In May 1812 Chief Little Turtle hosted a meeting of tribal leaders in the region in the Miami village of Mississinewa. Most of the tribes decided to remain neutral during the conflict and rejected Tecumseh's plans of continued rebellion.[91] Despite their rejection, Tecumseh continued to lead his dwindling army against the Americans, moving farther north so the British army could support them. Tecumshe's followers who remained behind continued to raid the countryside and engaged in the Siege of Fort Harrison, which was the U.S. Army's first land victory during the war.[92] John Gibson served as acting governor of the territory during the War of 1812, while Harrison was leading the army. After Harrison resigned, Gibson continued as acting-governor until Thomas Posey, the newly-appointed governor arrived in May 1813.[93]

Other battles that occurred during the war within the boundaries of the present-day state of Indiana include the Siege of Fort Wayne, the Pigeon Roost Massacre and the Battle of the Mississinewa. Most of the territory's native inhabitants remained passive throughout the war; however, numerous incidents between settlers and the native tribes led to the deaths of hundreds in the territory. The Treaty of Ghent (1814), ended the war and relieved American settlers from their fears of attack by the nearby British and their Indian allies.[94]

Movement toward statehood

On December 5, 1804, Governor Harrison issued a proclamation announcing the Indiana Territory's advancement to the second or semi-legislative phase of government. The territory's voters elected members to its House of Representatives for the first time on January 3, 1805; the governor selected the five-member Legislative Council (upper house) from a list of candidates that the elected representatives provided. The first legislative session of the territorial general assembly met in Vincennes from July 29 through August 16, 1805, and chose Benjamin Parke as its first delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives.[95]

Between 1805 and 1811 the northern portion of Indiana Territory was partitioned to establish Michigan Territory (1805) and the western portion of the territory set off to form the Illinois Territory (1809). In addition, Governor Harrison negotiated a series of treaties with native tribes that ceded additional lands within the Indiana Territory to the federal government, opening millions of acres for sale and settlement in the present-day southern of Indiana and most of Illinois. In 1810 antislavery supporters in the territorial legislature also succeeded in repealing the 1805 indenture law.[96]

Congressman Jonathan Jennings, Indiana Territory's congressional delegate

In late December 1811 and early January 1812, Jonathan Jennings, who had become the territory's first popularly-elected delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810,[97] presented the territorial legislature's petition to the U.S. Congress that requested permission to draft a state constitution for Indiana in preparation for statehood.[98] At that time the white population of the entire territory in 1810 was only 24,520, well below the threshold of 60,000 that the Northwest Ordinace required as a condition for statehood.[95][99] Congress took no action on the petition, largely due to the outbreak of the War of 1812.[100]

Thomas Posey was appointed territoral governor on March 3, 1813, and served until the state's first governor was sworn into office on November 7, 1816. Posey, who was age sixty-two and in poor health, had created a rift in the politics of the territory by refusing to reside in the capital of Corydon, instead living in Jeffersonville to be closer to his doctor.[101][102]

Achieving statehood

Efforts to attain statehood for Indiana were revived in 1815,[103] following a census made in 1814–15 that found the territory's total population had reached 63,897.[104] On February 1, 1815, a petition for statehood for Indiana was presented to the U.S. House of Representatives, but no immediate action was taken. Territorial legislature presented another petition to the U.S. House on December 28, 1815, and the U.S. Senate on January 2, 1816, prompting Jennings to introduce a bill to authorize the election of delegates to a constitutional convention to discuss statehood for Indiana.[105]

There was considerable disagreement between Jennings and Thomas Posey, the territorial governor, on the subject of statehood. Posey, who thought it was too early to petition for statehood for Indiana, argued that a state government would pose a fiscal burden on it residents and there would not be sufficient candidates to fill all the new state offices. He also supported slavery, much to the chagrin of his opponents, including Jennings, Dennis Pennington, and others in the territorial legislature and who sought to use the bid for statehood to permanently end the possibility of slavery in Indiana.[100][106] Posey's concerns were valid. If Indiana became a state it would lose the federal government subsidies it received to operate the territorial government. To support the new state government expenses and to offset the loss of the federal government subsidies, additional taxes would have to be levied on residents.[103] Supporters of statehood argued that the territory's residents were willing and capable of electing government officials to run the state government and wanted to have representatives in Congress who could vote on their behalf.[99][107]

On April 19, 1816, President James Madison approved an enabling act that the U.S. Congress passed on April 13. This act granted permission to convene a group of elected delegates tasked with drafting a state constitution,[105] subject to the approval of U.S. Congress,[108] that would establish the form of government for the new state. Elections of the forty-three delegates took place on May 13, 1816, and the constitutional convention assembled on June 10, 1816, in Corydon to begin their work. Convention delegates signed the state's first constitution on June 29, 1816, which immediately went into effect.[109][110]

Elections were held on August 5, 1816, to fill the offices of the new state government, including governor, lieutenant governor, a congressional representative, members of the Indiana General Assembly, and other offices. Jonathan Jennings defeated Thomas Posey to become the first governor of Indiana; Christopher Harrison was elected the state's first lieutenant governor; and William Hendricks was elected to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives.[111]

In November 1816 Congress approved the state constitution. The first session of the General Assembly for the state of Indiana convened on November 4, 1816. Jonathan Jennings and Christopher Harrison were inaugurated on November 7, 1816. On the following day the state legislature elected James Noble and Waller Taylor to represent Indiana in the U.S. Senate.[112][113] Hendricks, Noble, and Taylor were sworn into their congressional offices and took their seats in Congress in early December.[114] The dissolution of the territorial government ended the existence of the Indiana Territory.[115][116] On December 11, 1816, President James Madison signed the congressional resolution that formally admitted Indiana to the Union as the nineteenth state,[117] and federal laws were formally extended to the new state on March 3, 1817.[114]

Commemoration

Corydon old capitol

The Indiana Territory is celebrated at an annual event in Corydon that is centered around the territorial capitol building. The festival includes actors in period dress who portray some of the early settlers and reenact historical events.[118] Other commemorative festivals occur in Vincennes and Madison.[citation needed]

The history of the period is also noted on historic markers and monuments across the former territory. For example, an Indiana Boundary Territory Line state historical marker, erected in 1999 in La Porte County, Indiana, commemorates the establishment of the Indiana Territory's northern boundary when the Michigan Territory was formed in 1805.[119]

See also

- Historic regions of the United States

- History of Indiana

- Indiana Territory officials

Territorial evolution of the United States

U.S. territory from which the Territory of Indiana was created:

Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, 1787–1803

U.S. territory under the administration of the Territory of Indiana:

District of Louisiana, 1804–1805

U.S. territories that encompassed land that was previously part of the Territory of Indiana:

Territory of Michigan, 1805–1837

Territory of Illinois, 1809–1818

Territory of Wisconsin, 1836–1848

Territory of Minnesota, 1849–1858

U.S. states that encompass land that was once part of the Territory of Indiana:

State of Indiana, 1816

State of Illinois, 1818

State of Michigan, 1837

State of Wisconsin, 1848

State of Minnesota, 1858

- War of 1812

Notes

^ "Indiana". World Statesmen. Retrieved 20 July 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ James H. Madison and Lee Ann Sandweiss (2014). Hoosiers and the American Story. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780871953636.

^ ab Jervis Cutler and Charles Le Raye (1971). A Topographical Description of the State of Ohio, Indiana Territory, and Louisiana. New York: Arnot Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9780405028397. Reprint of 1812 edition.

^ John D. Barnhart and Dorothy L. Riker (1971). Indiana to 1816: The Colonial Period. The History of Indiana. 1. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Historical Society. pp. 311–12. OCLC 154955.

^ Darrel Bigham, ed. (2001). Indiana Territory, 1800-2000: A Bicentennial Perspective. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780871951557.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Cutler and Le Raye, pp. 110 and 112.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, p. 314.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 267–70.

^ Madison, p. 32.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, p. 312.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 360.

^ ab Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. pp. 18, 20, 28, 32, 37, and 40. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 323.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 405.

^ abc Barnhart and Riker, pp. 405–06.

^ Gugin and St. Clair, eds., pp. 28–31.

^ Jonathan Jennings was sworn into office as the first governor of the new state of Indiana on November 7, 1816. See Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 37.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 267–70.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, pp. 314, 317, and 324.

^ Dunn, p. 215.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 425.

^ abc Logan Esarey (1915). A History of Indiana. W. K. Stewart Company. pp. 170–72.

^ abc Barnhart and Riker, pp. 345–46, and p. 345, note 2.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 347, 351.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 356.

^ Buley, v. I, p. 62.

^ Funk, p. 201

^ "Thomas, Jess Burgess, (1777 - 1853)". Biographical Directory of Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

^ Buley, v. I, p. 61.

^ Randy K. Mills (2005). Jonathan Jennings: Indiana's First Governor. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 97–98, 104–5, and 156. ISBN 978-0-87195-182-3.

^ William Wesley Woollen (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 0-405-06896-4.

^ Donald Carmony (September 1943). "Indiana Territorial Expenditures, 1800–1816" (PDF). Indiana Magazine of History. 39 (3): 242. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

^ Carmony, pp. 255–56, 259.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 405–06; Gugin and St. Clair, eds., pp. 28–31.

^ The office of auditor was created by Congress in 1809 and filled in the next general election

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 432–33.

^ Bennett, ed., p. 11.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 413, 433–34.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 414–15, 421.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 421–23, 442.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, pp. 369–70.

^ Bigham, pp. 12–14.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 334–36.

^ ab Gresham, p. 21

^ Terms of servitude for an adult slave could extend beyond the slave's life. Slaves under the age of fifteen were required to serve until they reach age thirty-five for males and thirty-two for females. Children born to slaves after they arrived in the territory were bound into service for thirty years for males and twenty-eight years for females. See: Barnhart and Riker, p. 348.

^ Dunn, p. 218

^ By the same act, Congress removed the General Court's legislative power, creating a legislative council to be elected by popular vote, enabling the Indiana Territory to enter the second phase of territorial government. See Dunn, p. 246

^ Dunn, pp. 249 and 298

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 349.

^ Dunn, p. 258

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 327 and 361.

^ ab Gresham, p. 25

^ ab Robert M. Taylor Jr.; Erroll Wayne Stevens; Mary Ann Ponder; Paul Brockman (1989). Indiana: A New Historical Guide. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 169. ISBN 0871950499. Also: Ray E. Boomhower (2000). Destination Indiana: Travels Through Hoosier History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 17. ISBN 0871951479.

^ "Congressional Record". 1st United States Congress. August 7, 1789. pp. 50–51. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

^ Cyrus Hodgin, "The Naming of Indiana," in "Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society". 1 (1). 1903: 3–11. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

^ Madison and Sandweiss, p. 40.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 287.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 283–87.

^ James H. Madison (2014). Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and the Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-253-01308-8.

^ Gregory Evans Dowd (1992). A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 113–14. ISBN 0-8018-4236-0.

^ ab Madison, p. 29.

^ R. Carlyle Buley (1950). The Old Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815-1840. I. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 18.

^ Arville L. Funk (1983) [1969]. A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, Indiana: Christian Book Press. p. 38.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 303–07.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 311–13.

^ Judge Law (1858). The Colonial History of Vincennes. Harvey, Mason and Company. p. 57. Reproduced 2006.

^ ab Madison, p. 34.

^ In addition to his duties as acting governor, John Gibson served as the first secretary of the Indiana Territory from July 4, 1800, to November 7, 1816. See Gugin and St. Clair, eds., pp. 28–31. Also: Barnhart and Riker, pp. 317, 323, and 405–06.

^ Harrison resigned his position as territorial governor on December 28, 1812, to continue his military and political career. He gained national fame as a hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811) and became the ninth President of the United States (1841); Harrison County was named in his honor. See: Jacob Piatt Dunn Jr. (1919). Indiana and Indianans. I. Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society. p. 228.

Also: "Indiana History Part 2". Northern Indiana Center for History. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

^ Dunn, p. 215.

^ Dunn, p. 225–226

^ Bigham, p. 7.

^ Pamela J. Bennett, ed. (March 1999). "Indiana Territory" (pdf). The Indiana Historian. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2018.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 317.

^ George Pence and Nellie C. Armstrong (1933). Indiana Boundaries: Territory, State, and County. Indiana Historical Collections. 19. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau. pp. 21–22. OCLC 12704244. Reprinted, 1967.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 324.

^ Some sources indicate that there were only thirteen counties by 1816, see Barnhart and Riker, p. 427, for example; however, other sources identify fifteen counties: Clark, Dearborn, Franklin, Gibson, Harrison, Jackson, Jefferson, Knox, Orange, Perry, Posey, Switzerland, Warrick, Washington, and Wayne. See: Pence and Armstrong, pp. 26–27.

^ abc Isaac Rand Jackson (1840). A Sketch of the Life and Public Services of William Henry Harrison. Columbus, Ohio: I. N. Whitting. p. 7.

^ Madison, p. 39.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, pp. 342–43.

^ Louisiana Purchase lands south of the 33rd parallel, the more densely populated "territory of Orleans," was separately administered, largely under civil law.[citation needed]

^ One Kansas Territory source, recounting Kansas history up to 1855, states that Kansas, as part of the district of Louisiana, was not only administered by, but also "annexed to", Indiana Territory. Whether a temporary act can effect an annexation may depend on its actual duration, and most sources have declined to call Indiana Territory administration an annexation or even to use the term "annexed to". Less persuasively, maps generally fail to reflect the de jure common governance of Indiana Territory and the [D]istrict of Louisiana by way of, say, a common color scheme and/or a dotted border.[citation needed]

^ "Congressional Record". 8th United States Congress. March 3, 1805. p. 331. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

^ Charles J. Kappler, ed. (November 3, 1804). Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1804. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1804. Retrieved September 30, 2008.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link) 7 Stat., 84. Ratified January 25, 1805, proclaimed February 21, 1805.

^ Madison, p. 41.

^ A. J. Langguth (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 158–60. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6.

^ Langguth, pp. 164–66.

^ Langguth, pp. 167–69.

^ Freeman Cleeves (1939). Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and His Time. New York: Scribner's. p. 3.

^ Dunn, p. 282.

^ Dunn, p. 266.

^ Dunn, p. 267.

^ Dunn, p. 283.

^ Fred L. Engleman. "The Peace of Christmas Eve". American Heritage. American Heritage.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

^ ab Bigham, pp. 8–10.

^ Madison and Sandweiss, pp. 43–44, 46–47.

^ Dunn, p. 263

^ Buley, v. 1, p. 65.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, pp. 405–06, 430.

^ ab Dunn, p. 293

^ According to some sources Thomas Posey refused to live in Corydon because of his ongoing quarrel with Dennis Pennington. See Gresham, p. 22.

^ Dunn, p. 283–84.

^ ab Madison, p. 49.

^ Dennis Pennington was named as the census enumerator. Historical sources report varying census totals, but most secondary sources list the total population as 65,897, which is the census figure submitted to the territory's House of Representatives. See Barnhart and Riker, p. 427, note 39; Bennett, ed., p. 6; and William S. Haymond (1879). An Illustrated History of the State of Indiana. S. L. Marrow and Company. p. 181.

^ ab Buley, v. I, p. 67.

^ In addition, Posey was soliciting his reappointed from the U.S. president to another term as the territorial governor and therefore had a professional interest in maintaining the territorial government. See Barnhart and Riker, p. 430.

^ Madison, p. 51.

^ Funk, p. 42.

^ Buley, v. I, pp. 67, 69.

^ Barnhart and Riker, pp. 441–44, 460.

^ Barnhart and Riker, p. 461.

^ Bennett, ed., p. 6.

^ Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 42.

^ ab Barnhart and Riker, pp. 461–62.

^ Funk, p. 35.

^ "Indiana History Part 3". Indiana Center For History. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

^ Madison and Sandweiss, p. 44.

^ "Indiana Territory Festival". Harrison County Tourism Board. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

^ In 1816, when Indiana became a state, the state's boundary was moved ten miles north, providing Indiana with additional miles of shoreline along Lake Michigan. See: "Indiana Territory Boundary Line". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Barnhart, John D., and Dorothy L. Riker (1971). Indiana to 1816: The Colonial Period. The History of Indiana. 1. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Historical Society. OCLC 154955.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Bennett, Pamela J., ed. "Indiana Territory" (pdf). The Indiana Historian. Retrieved July 24, 2018.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Bigham, Darrel, ed. (2001). Indiana Territory, 1800-2000: A Bicentennial Perspective. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 9780871951557.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Boomhower, Ray E. (2000). Destination Indiana: Travels Through Hoosier History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0871951479.

Buley, R. Carlyle (1950). The Old Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815-1840. I and II. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.

Carmony, Donald (September 1943). "Indiana Territorial Expenditures, 1800–1816" (pdf). Indiana Magazine of History. 39 (3): 237–62. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

Cleaves, Freeman (1939). Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and His Time. New York: Scribner's.

"Congressional Record". 1st U.S. Congress. August 7, 1789. pp. 50–51. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

"Congressional Record". 8th U.S. Congress. March 3, 1805. p. 331. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

Cutler, Jervis, and Charles Le Raye (1971). A Topographical Description of the State of Ohio, Indiana Territory, and Louisiana. Arnot Press. ISBN 978-0-405-02839-7.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) (Reprint of 1812 edition.)

Dowd, Gregory Evans (1992). A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4236-0.

Dunn Jr., Jacob Piatt (1919). Indiana and Indianans. I. Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society.

Engleman, Fred L. "The Peace of Christmas Eve". American Heritage.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

Esarey, Logan (1915). A History of Indiana. W. K. Stewart Company.

Funk, Arville L. (1983) [1969]. A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, Indiana: Christian Book Press.

Gresham, Matilda (1919). Life of Walter Quintin Gresham, 1832-1895. Rand McNally and company.

Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Haymond, William S. (1879). An Illustrated History of the State of Indiana. S. L. Marrow and Company.

"Indiana". World Statesmen. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

"Indiana History Part 2". Northern Indiana Center for History. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

"Indiana History Part 3". Indiana Center For History. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

"Indiana Territory Boundary Line". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

"Indiana Territory Festival". Harrison County Tourism Board. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

Jackson, Isaac Rand (1840). A Sketch of the Life and Public Services of William Henry Harrison. Columbus, Ohio: I. N. Whiting.

"Jennings, Jonathan, (1784 - 1834)". Biographical Directory of Congress. U.S. Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

Kappler, Charles J., ed. (November 3, 1804). Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1804. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved September 30, 2008.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link) 7 Stat., 84. Ratified January 25, 1805, proclaimed February 21, 1805.

Langguth, A. J. (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6.

Law, Judge (1858). The Colonial History of Vincennes. Harvey, Mason and Company. (Reproduced 2006)

Madison, James H. (2014). Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and the Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01308-8.

Madison, James H., and Lee Ann Sandweiss (2014). Hoosiers and the American Story. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-363-6.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Mills, Randy K. Mills (2005). Jonathan Jennings: Indiana's First Governor. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-182-3.

Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society. 1, Number 1. 1903. pp. 3–11. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

"Parke, Benjamin". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

"Parke, Benjamin, (1777 – 1835)". Biographical Directory of Congress. U.S. Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

Taylor Jr., Robert M.; Erroll Wayne Stevens; Mary Ann Ponder; Paul Brockman (1989). Indiana: A New Historical Guide. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0871950499.

"Thomas, Jess Burgess, (1777 - 1853)". Biographical Directory of Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

Woodfill, Roger. "Greenville and Grouseland Treaty Lines". Backsights. Surveyors Historical Society. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-405-06896-4.

External links

Act Creating Indiana Territory, 1800, text, Indiana Historical Bureary, Indianapolis

Act Dividing the Indiana Territory, 1805, text, Indiana Historical Bureau

Act Dividing the Indiana Territory, 1809, text, Indiana Historical Bureau

Proclamation: Announcing that Indiana Territory Had Passed to the Second Grade, text, Indiana Historical Bureau- Other acts concerning the Indiana Territory