Camorra

| Founded | since the 17th century |

|---|---|

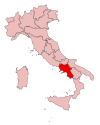

| Founding location | Campania, Italy |

| Territory |

|

| Membership | about 7,000[1] |

| Criminal activities | Racketeering, drug trafficking, counterfeiting, waste management, murder, bid rigging, extortion, assault, smuggling, illegal gambling, terrorism, loan sharking, prostitution, money laundering, robbery |

| Allies | Sicilian Mafia Sacra Corona Unita 'Ndrangheta Banda della Magliana Greek mafia |

The Camorra (Italian: [kaˈmɔrra]; Neapolitan: [kaˈmorrə]) is an Italian Mafia-type[2]crime syndicate, or secret society, which arose in the region of Campania and its capital Naples. It is one of the oldest and largest criminal organizations in Italy, dating back to the 17th century. Unlike the pyramidal structure of the Sicilian Mafia, the Camorra's organizational structure is more horizontal than vertical. Consequently, individual Camorra clans act independently of each other, and are more prone to feuding among themselves.

Contents

1 Background

2 Activities

3 Refuse crisis

4 Efforts to fight the Camorra

5 Outside Campania and Italy

5.1 Camorra in the United Kingdom

5.2 Camorra in the United States

6 In popular culture

7 See also

8 References

8.1 Sources

9 Further reading

10 External links

Background

The origins of the Camorra are not entirely clear. It may date back to the 17th century as a direct Italian descendant of a Spanish secret society, the Garduña, founded in 1417. Officials of the Kingdom of Naples may have introduced the organization to the area, or it may have grown gradually out of small criminal gangs operating in Neapolitan society near the end of the 18th century.[3] However, recent historical research in Spain suggests that the Garduña never really existed and was based on a fictional 19th century book.[4]

The first official use of the word dates from 1735, when a royal decree authorised the establishment of eight gambling houses in Naples. The word is likely a blend, or portmanteau, of "capo" (boss) and a Neapolitan street game, the "morra".[3][5] (In this game, two persons wave their hands simultaneously, while a crowd of surrounding gamblers guess, in chorus, at the total number of fingers exposed by the principal players.)[6] This activity was prohibited by the local government, and some people started making the players pay for being "protected" against the passing police.[3][7][8]

Camorristi in Naples, 1906

The Camorra first emerged during the chaotic power vacuum in the years between 1799 and 1815, when the Parthenopean Republic was proclaimed on the wave of the French Revolution and the Bourbon Restoration. The first official mention of the Camorra as an organization dates from 1820, when police records detail a disciplinary meeting of the Camorra, a tribunal known as the Gran Mamma. That year a first written statute, the frieno, was also discovered, indicating a stable organisational structure in the underworld. Another statute was discovered in 1842, including initiation rites and funds set aside for the families of those imprisoned. The organization was also known as the Bella Società Riformata, Società dell'Umirtà or Onorata Società.[9][10]

The evolution into more organized formations indicated a qualitative change: the Camorra and camorristi were no longer local gangs living off theft and extortion; they now had a fixed structure and some kind of hierarchy. Another qualitative leap was the agreement of the liberal opposition and the Camorra, following the defeat in the 1848 revolution. The liberals realized that they needed popular support to overthrow the king. They turned to the Camorra and paid them, the camorristi being the leaders of the city’s poor. The new police chief, Liborio Romano, turned to the head of the Camorra, Salvatore De Crescenzo, to maintain order and appointed him as head of the municipal guard.[11] The Camorra effectively had developed into power brokers in a few decades.[9] In 1869, Ciccio Cappuccio was elected as the capintesta (head-in-chief) of the Camorra by the twelve district heads (capintriti), succeeding De Crescenzo after a short interregnum.[12] Nicknamed 'The king of Naples' ('‘o rre 'e Napole) he died in 1892.[13][14]

Following Italian unification in 1861 attempts were made to tackle the Camorra and a series of manhunts were made from 1882 on. The Saredo Inquiry (1900–1901), established to investigate corruption and bad governance in Naples, identified a system of political patronage ran by what the report called the "high Camorra":

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The original low camorra held sway over the poor plebs in an age of abjection and servitude. Then there arose a high camorra comprising the most cunning and audacious members of the middle class. They fed off trade and public works contracts, political meetings and government bureaucracy. This high camorra strikes deals and does business with the low camorra, swapping promises for favours and favours for promises. The high camorra thinks of the state bureaucracy as being like a field it has to harvest and exploit. Its tools are cunning, nerve and violence. Its strength comes from the streets. And it is rightly considered to be more dangerous, because it has re-established the worst form of depotism by founding a regime based on bullying. The high camorra has replaced free will with impositions, it has nullified individuality and liberty, and it has defrauded the law and public trust.[15][16]

The Inquiry introduced the terminology of "high Camorra", with a bourgeois character, but distinct from the plebeian Camorra proper, although both were in close contact through the figure of the intermediary (faccendiere).[17]

From the rich industrialist who wants a clear road into politics or administration to the small shopowner who wants to ask for a reduction of taxes; from the businessman trying to win a contract to a worker looking for a job in a factory; from a professional who wants more clients or greater recognition to somebody looking for an office job; from somebody from the provinces who has come to Naples to buy some goods to somebody who wants to emigrate to America; they all find somebody stepping into their path, and nearly all made use of them.[18]

However, whether the "high Camorra" was an integral part of the Camorra proper is disputed.[16] Although the inquiry did not prove specific collusion between the Camorra and politics, it brought to light the patronage mechanisms that fueled corruption in the municipality.[15] The society's influence was weakened which was exemplified by the defeat of all of their candidates in the 1901 Naples election. Many camorristi left for the United States in the early 20th century.[19]

The Cuocolo trial in Viterbo. Most of the defendants are in the large cage. The three in front are (from left to right) the priest Ciro Vitozzi, Maria Stendardo, the only female defendant, and Enrico Alfano. In the small cage to the right is the crown witness Gennaro Abbatemaggio.

The Camorra received another blow with the Cuocolo trial (1911–1912). While the trial was about the murder of the Camorrista Gennaro Cuocolo and his wife, suspected of being police spies, on June 6, 1906, the main investigator, Carabinieri Captain Carlo Fabbroni, transformed it from a murder trial into one against the Camorra as a whole. Fabbroni intended to use the trial to strike the final blow to the Camorra.[20][21] The trial attracted a lot of attention of newspapers and the general public both in Italy as well as in the United States, including by Pathé's Gazette.[22] The hearings began in the spring of 1911 and would continue for twelve months. After a 17-month trial, the often tumultuous proceedings ended with a guilty verdict on July 8, 1912. The defendants, including 27 leading Camorra bosses, were sentenced to a total of 354 years' imprisonment. The main defendant and nominal head of the Camorra, Enrico Alfano, was sentenced to 30 years.[20][23][24][25]

The Camorra was never a coherent whole nor a centralised organization. Instead, it has always been a loose confederation of different, independent groups or families. Each group was bound around kinship ties and controlled economic activities which took place in its particular territory. Each family clan took care of its own business, protected its territory, and sometimes tried to expand at another group’s expense. Although not centralized, there was some minimal coordination, to avoid mutual interference. The families competed to maintain a system of checks and balances between equal powers.[26]

One of the Camorra's strategies to gain social prestige is political patronage. The family clans became the preferred interlocutors of local politicians and public officials, because of their grip on the community. In turn, the family bosses used their political sway to assist and protect their clients against the local authorities. Through a mixture of brute force, political status, and social leadership, the Camorra family clans imposed themselves as middlemen between the local community and bureaucrats and politicians at the national level. They granted privileges and protection, and intervened in favour of their clients in return for their silence and connivance against local authorities and the police. With their political connections, the heads of the major Neapolitan families became power brokers in local and national political contexts, providing Neapolitan politicians with broad electoral support, and in return receiving benefits for their constituency.[26]

Activities

Compared to the Sicilian Mafia's pyramidal structure, the Camorra has more of a 'horizontal' than a 'vertical' structure. As a result, individual Camorra clans act independently of each other, and are more prone to feuding among themselves. This however makes the Camorra more resilient when top leaders are arrested or killed, with new clans and organizations germinating out of the stumps of old ones. As the Galasso clan boss Pasquale Galasso once stated in court; "Campania can get worse because you could cut into a Camorra group, but another ten could emerge from it."[27]

In the 1970s and 1980s Raffaele Cutolo made an attempt to unify the Camorra families in the manner of the Sicilian Mafia, by forming the New Organized Camorra (Nuova Camorra Organizzata or NCO), but this proved unsuccessful. Drive-by shootings by camorristi often result in casualties among the local population, but such episodes are often difficult to investigate because of widespread omertà (code of silence). According to a report from Confesercenti, the second-largest Italian Trade Organization, published on October 22, 2007 in the Corriere della Sera, the Camorra control the milk and fish industries, the coffee trade, and over 2,500 bakeries in Naples.[28]

In 1983, Italian law enforcement estimated that there were only about a dozen Camorra clans. By 1987, the number had risen to 26, and in the following year, a report from the Naples flying squad reported their number as 32. Currently it is estimated there are about 111 Camorra clans and over 6,700 members in Naples and the immediate surroundings.[29]Roberto Saviano, an investigative journalist and author of Gomorra, an exposé of the activities of the Camorra, says that this sprawling network of Camorra clans now dwarfs the Sicilian Mafia, the 'Ndrangheta and southern Italy's other organised gangs, in numbers, in economic power and in ruthless violence.[30]

In 2004 and 2005 the Di Lauro clan and the so-called Scissionisti di Secondigliano fought a bloody feud which came to be known in the Italian press as the Scampia feud. The result was over 100 street killings. At the end of October 2006 a new series of murders took place in Naples between 20 competing clans, that cost 12 lives in 10 days. The Interior Minister Giuliano Amato decided to send more than 1,000 extra police and carabinieri to Naples to fight crime and protect tourists.[31] Despite this, in the following year there were over 120 murders.[citation needed]

In 2001 the businessman Domenico Noviello from Caserta testified against a Camorra extortionist and subsequently received police protection. In 2008 he refused further protection and was killed one week later.[32]

In recent years, various Camorra clans have been allegedly utilizing alliances with Nigerian drug gangs and the Albanian mafia. Augusto La Torre, the former La Torre clan boss who became a pentito, is married to an Albanian woman. It should also be noted that the first foreign pentito, a Tunisian, admitted to being involved with the feared Casalesi clan of Casal di Principe. The first town in which the Camorra sanctioned stewardship by a foreign clan was Castel Volturno, which was given to the Rapaces, clans from Lagos and Benin City in Nigeria. This allowed them to traffic cocaine and women in sexual slavery before sending them across the whole of Europe.[33]

Refuse crisis

Since the mid-1990s, the Camorra has taken over the handling of refuse disposal in the region of Campania, with disastrous results for the environment and the health of the general population. Heavy metals, industrial waste, chemicals and household garbage are frequently mixed together, then dumped near roads and burnt to avoid detection, leading to severe soil and air pollution.

The situation worsened during this period as the camorra diversified their illegal waste disposal strategy: 1) transporting and dumping hazardous waste in the countryside by truck; 2) dumping waste in illegal caves or holes; 3) mixing toxic waste with textiles to avoid explosions and then burning it; and 4) mixing toxic with urban waste for disposal in landfills and incinerators.[34]

With the assistance of private businessmen known as "stakeholders", the numerous Camorra clans are able to gain massive profits from under-the-table contracts with local, legitimate businesses. These "stakeholders" are able to offer companies highly lucrative deals to remove their waste at a significantly lower price. With little to no overhead, Camorra clans and their associates see very high profit margins. According to author Roberto Saviano, the Camorra uses child labour to drive the waste in for a small price, as they do not complain about the health risks as the older truckers might.

As of June 2007, the region has no serviceable dumping sites, and no alternatives have been found. Together with corrupt local officials and unscrupulous industrialists from all over Italy, the Camorra has created a cartel that has so far proven very difficult for officials to combat.[35]

In November 2013 a demonstration by tens of thousands of people was held in Naples in protest against the pollution caused by the Camorra's control of refuse disposal. Over a twenty-year period, it was alleged, about ten million tonnes of industrial waste had been illegally dumped, with cancers caused by pollution increasing by 40–47%.[36]

Efforts to fight the Camorra

The Camorra has proven to be an extremely difficult organization to fight within Italy. At the first mass trial against the Camorra in 1911–12, Captain Carlo Fabroni of the Carabinieri gave testimony on how complicated it was to successfully prosecute the Camorra: "The Camorrist has no political ideals. He exploits the elections and the elected for gain. The leaders distribute bands throughout the town, and they have recoursed to violence to obtain the vote of the electors for the candidates whom they have determined to support. Those who refuse to vote as instructed are beaten, slashed with knives, or kidnapped. All this is done with assurance of impunity, as the Camorrists will have the protection of successful politicians, who realize that they cannot be chosen to office without paying toll to the Camorra."[37]

The trial that investigated the murder of the camorrista Gennaro Cuocolo was followed with great interest by the newspapers and the general public. It led to the conviction of 27 leading Camorra bosses, who were sentenced to a total of 354 years of imprisonment, including the head of the Camorra at the time, Enrico Alfano.[38][39]

Unlike the Sicilian Mafia, which has a clear hierarchy and a division of interests, the Camorra's activities are much less centralized. This makes the organization much more difficult to combat through crude repression.[40] In Campania, where unemployment is high and opportunities are limited, the Camorra has become an integral part of the fabric of society. It offers a sense of community and provides the youth with jobs. Members are guided in the pursuit of criminal activities, including cigarette smuggling, drug trafficking, and theft.[41]

The government has made an effort to combat the Camorra's criminal activities in Campania. The solution ultimately lies in Italy's ability to offer values, education and work opportunities to the next generation. However, the government has been hard pressed to find funds for promoting long term reforms that are needed to improve the local economic outlook and create jobs.[41] Instead, it has had to rely on limited law enforcement activity in an environment which has a long history of criminal tolerance and acceptance, and is governed by a code of silence or omertà that persists to this day.[42]

Despite the overwhelming magnitude of the problem, law enforcement officials continue their pursuit. The Italian police are coordinating their efforts with Europol at the European level as well as Interpol to conduct special operations against the Camorra. The Carabinieri and the Financial Police (Guardia di Finanza) are also fighting criminal activities related to tax evasion, border controls, and money laundering. Prefect Gennaro Monaco, Deputy Chief of Police and Chief of the Section of Criminal Police cites "impressive results" against the Camorra in recent years, yet the Camorra continues to grow in power.[43]

In 1998, police took a leading Camorra figure into custody. Francesco Schiavone was caught hiding in a secret apartment near Naples behind a sliding wall of granite. The mayor of Naples, Antonio Bassolino, compared the arrest to that of Sicilian Mafia chief Salvatore Riina in 1993.[44] Francesco Schiavone is now serving a life sentence after a criminal career which included arms trafficking, bomb attacks, armed robbery, and murder.

Michele Zagaria, a senior member of the Casalesi clan, was arrested in 2011 after eluding police for 16 years. He was found in a secret bunker in the town Casapesenna, near Naples.[45] In 2014, clan boss Mario Riccio was arrested for drug trafficking in the Naples area. Around the same time 29 suspected Camorra members were also arrested in Rome.[46]

The arrests in the Campania region demonstrate that the police are not allowing the Camorra to operate without intervention. However, progress remains slow, and these minor victories have done little to loosen the Camorra's grip on Naples and the surrounding regions.[41]

In 2008, Italian police arrested three members of the Camorra crime syndicate on September 30, 2008. According to Gianfrancesco Siazzu, commander of the Carabinieri police, the three were captured in small villas on the coast of Naples. All three had been on Italy's 100 top most wanted list. Police seized assets valued at over 100 million euros and also weapons, including two AK-47 assault rifles that may have been used in the shooting of six Africans on September 18, 2008. Police found pistols, Carabinieri uniforms and other outfits that were used to disguise members of the operation. During the same week, a separate operation netted 26 additional suspects in Caserta. All were believed to belong to the powerful Camorra crime syndicate that operates in and around Naples. The suspects were charged with extortion and weapons possession. In some cases, the charges also included murder and robbery. Giuseppina Nappa, the 48-year-old wife of a jailed crime boss, was among those arrested. She is believed to be the Camorra's local paymaster.[47]

In November 2018, Italian police announced the arrest of Antonio Orlando, suspected of being a major figure in the Camorra.[48]

Outside Campania and Italy

Despite its origins, it presently has secondary ramifications in other Italian regions, like Lombardy,[49][50][51]Piedmont[52][53] and Emilia-Romagna,[54][55] in connection with the centers of national economic power. It has also spread outside the Italy's boundaries, and acquired a foothold in the United Kingdom and United States.

Camorra in the United Kingdom

Scotland has had its brush with the Camorra. Antonio La Torre of Aberdeen was the local "Don" of the Camorra. He is the brother of Camorra boss Augusto La Torre of the La Torre clan which had its base in Mondragone, Caserta. The La Torre Clan's empire was worth hundreds of millions of euros. Antonio had several legitimate businesses in Aberdeen, whereas his brother Augusto had several illegal businesses there. He was convicted in Scotland and is awaiting extradition to Italy.[needs update] Augusto would eventually become a pentito in January 2003, confessing to over 40 murders and his example would be followed by many of his men.[56]

Two Aberdeen restaurateurs, Ciro Schiattarella and Michele Siciliano, were extradited to Italy for their part in the "Aberdeen Camorra". A fourth Scottish associate made history by becoming the first foreign member of the Camorra and is currently serving a jail sentence in the UK. It has been reported that he also receives a monthly salary, legal assistance and protection.[57]

Saviano alleges that from the 1980s, Italian gangsters ran a network of lucrative businesses in the city as well as many illegal rackets. Saviano said Scotland's third city, with no history of organized crime, was seen as an attractive safe haven away from the violent inter-gang bloodletting that had engulfed their Neapolitan stronghold of Mondragone. Saviano claims that before the Italian clans arrived, Aberdeen did not know how to exploit its resources for recreation and tourism. He further states that the Italians infused the city with economic energy, revitalised the tourist industry, inspired new import-export activities and injected new vigour in the real-estate sector. It thereby turned Aberdeen into a chic, elegant address for fine dining and important dealings.[57]

The hub of La Torre's UK empire, Pavarotti's restaurant, now under different ownership, was even feted at Italissima, a prestigious gastronomic fair held in Paris. The restaurant was even advertised on the city's local tourist guides. Saviano further claims to have gone to Aberdeen and worked in a restaurant run by Antonio La Torre. The Camorristas operated a system known as "scratch" where they used to step up illegal activities if their legitimate ventures were struggling. If cash was short they had counterfeit notes printed; if capital was needed in a hurry, they sold bogus treasury bonds. They annihilated the competition through extortions and imported merchandise tax-free. The Camorra were able to run all sort of deals because the local police had virtually no experience in dealing with organized crime. Although they broke the law, there were never any guns or serious violence, due to lack of rivals.[57]

However, the suggestion that the city remains in the grip of mobsters has been strongly denied by leaders of the 300 strong Italian community in Aberdeen. Moreover, Giuseppe Baldini, the Italian government's vice-consul in Aberdeen, denies that the Camorra still maintains its presence in Aberdeen.[57]

Camorra in the United States

The Camorra existed in the United States between the mid-19th century and early 20th century. They rivaled the defunct Morello crime family for power in New York. Eventually, they melded with the early Italian-American Mafia groups.

Many Camorra members and associates fled the internecine gang warfare and Italian Justice and immigrated to the United States in the 1980s. In 1993, the FBI estimated that there were 200 camorristi in the United States. Although there appears to be no clan structure in the United States, Camorra members have established a presence in Los Angeles, New York and Springfield, Massachusetts.[58] The Camorra is the least active of all the organized crime groups in the United States.[59] In spite of this, the US law enforcement considers the Camorra to be a rising criminal enterprise, especially dangerous because of its ability to adapt to new trends and forge new alliances with other criminal organizations.[60]

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation:

In the 1970s, the Sicilian Mafia convinced the Camorra to convert their cigarette smuggling routes into drug smuggling routes with the Sicilian Mafia's assistance. Not all Camorra leaders agreed, leading to the Camorra Wars that cost 400 lives. Opponents of drug trafficking lost the war. The Camorra made a fortune in reconstruction after an earthquake ravaged the Campania region in 1980. Now it specializes in cigarette smuggling and receives payoffs from other criminal groups for any cigarette traffic through Italy. The Camorra is also involved in money laundering, extortion, alien smuggling, robbery, blackmail, kidnapping, political corruption, and counterfeiting. It is believed that nearly 200 Camorra affiliates reside in this country, many of whom arrived during the Camorra Wars.[61]

In 1995, the Camorra cooperated with the Russian Mafia in a scheme in which the Camorra would bleach out US $1 bills and reprint them as $100s. These bills would then be transported to the Russian Mafia for distribution in 29 post-Eastern Bloc countries and former Soviet republics.[58] In return, the Russian Mafia paid the Camorra with property (including a Russian bank) and firearms, smuggled into Eastern Europe and Italy.[60]

In 2012, the Obama administration imposed sanctions on the Camorra as one of four key transnational organized crime groups, along with the Brothers' Circle from Russia, the Yamaguchi-gumi (Yakuza) from Japan, and Los Zetas from Mexico.[62]

In popular culture

Camorra is a 1972 film, directed by Pasquale Squitieri, starring Fabio Testi and Jean Seberg.- "Commendatori", an episode of The Sopranos which features the Camorra.

Il camorrista (1986), directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Vaguely inspired by the real story of NCO boss, Raffaele Cutolo. Cutolo is played by Ben Gazzara, with the Italian voiceover done by Italian actor Mariano Rigillo.

Roberto Saviano's 2006 book Gomorra investigates the activities of the Camorra in Italy, especially in the Provinces of Naples and Caserta. Matteo Garrone adopted the book into a 2008 film, Gomorra, describing low level Camorra foot-soldiers, and in 2014 into a TV series of the same name.- The 2009 film Fortapàsc (English: Fort Apache Napoli) directed by Marco Risi about the brief life and death of journalist Giancarlo Siani, murdered by camorrisiti from the Nuvoletta clan.[63]

- The opera I gioielli della Madonna by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari features the Camorra as part of the plot.

- The story of Raffaele Cutolo also inspired one of the most famous songs of Fabrizio De André, entitled Don Raffaé (Clouds of 1990).

- The Camorra (depicted as a hooded secret society) appear as villains in an episode of The Wild Wild West, "The Night of the Dancing Death."

- Also referenced in an episode of Archer (Season 4, Episode 11) when a plot against the pope was being carried out by Camorra grunts.

- In the Japanese light novel series and anime Baccano!, a handful of the main characters are part of the Camorra group known as the Martillo Family, and become quite insulted if they are mistaken for the Mafia.

- Elena Ferrante's four Neapolitan Novels are concerned with the damage done by the Camorra portrayed as the two Solara brothers.

- In Rei Hiroe's manga Black Lagoon, during the "El baile De La Muerte"/"Roberta's Blood Trail" arc, a man called Tomazo makes his appearance. Tomazo is on the side of the Italian mob leader Ronnie the jaws. Later it is revealed that Tomazo is a member of the Camorra, and his surname Falcone as well.

- In John Wick: Chapter 2, main antagonist Santino D'Antonio is a member of the Camorra.

- In the short story "The Fate of Faustina" by E. W. Hornung, it is revealed that the main character and criminal-in-hiding A. J. Raffles has made an enemy of a high-level member of the Camorra from his time spent in Italy. In the sequel story, "The Last Laugh", the Camorra try to realize that threat and kill Raffles; however, Raffles not only saves himself from his attackers but also tricks them into poisoning themselves.

See also

- List of members of the Camorra

- List of Camorra clans

- Naples waste management issue

- Triangle of death (Italy)

References

^ "FBI — Italian/Mafia". FBI. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Mafia and Mafia-type organizations in Italy Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, by Umberto Santino, in: Albanese, Das & Verma, Organized Crime. World Perspectives, pp. 82-100

^ abc Behan, The Camorra, pp. 9–10

^ (in Spanish) Interview with historian Hipólito Sánchiz Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Minuto digital, December 11, 2006

^ (in Italian) Il gioco della morra, Biblioteca digitale sulla Camorra (accessed May 25, 2011)

^ Purity, Time Magazine, July 30, 1923 Archived August 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

^ Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, p. 23

^ (in Italian) Camorra, alle radici del male, Narcomafie on line, October 29, 2001 Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

^ ab Behan, The Camorra, pp. 12

^ Sales, La camorra, le camorre, pp. 72–73

^ (in Italian) Paliotti, Storia della Camorra, pp. 149–153

^ (in Italian) Paliotti, Storia della Camorra, p. 143

^ (in Italian) La morte di Ciccio Cappuccio, Il Mattino, December 6, 1892

^ (in Italian) Di Fiore, Potere camorrista: quattro secoli di malanapoli, p. 96–97

^ ab (in Italian) La lobby di piazza Municipio: gli impiegati comunali nella Napoli di fine Ottocento, by Giulio Machetti, Meridiana, pp. 38–39, 2000

^ ab Dickie, Mafia Brotherhoods, pp. 88–89

^ (in Italian) L'Inchiesta Saredo, by Antonella Migliaccio, Cultura della Legalità e Biblioteca digitale sulla Camorra, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell'Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (Access date: September 5, 2016)

^ Behan, The Camorra, pp. 263-64

^ "Camorra - Italian secret society". britannica.com.

^ ab The Cuocolo trial: the Camorra in the dock, Museo criminologico (Retrieved May 25, 2011)

^ Cuocolo Trial May Be Death Blow of the Camorra, The New York Times, March 5, 1911

^ Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods, p. 191

^ Behan, The Camorra, p. 23

^ Camorrist Leaders Get 30-Year Terms, The New York Times, July 9, 1912

^ Camorra Verdict; All Found Guilty, New York Tribune, July 9, 1912

^ ab Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, p. 24

^ Behan, Camorra, pp. 184

^ "Die Mafia ist Italiens führendes Unternehmen", Die Welt, October 23, 2007

^ Behan, Tom (1996). The Camorra. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 9780415099875.

^ "Man who took on the Mafia: The truth about Italy's gangsters". The Independent. October 16, 2006.

^ Paul Kreiner (November 6, 2006). "Mit mehr Polizei gegen die Camorra". Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Hammer, Joshua (July 6, 2015). "Why Does the Mob Want to Erase This Writer?". GQ.

^ "Roberto Saviano on the Italian Camorra". Cafe Babel. October 8, 2007. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009.

^ D'Alisa, Giacomo; Burgalassi, David; Healy, Hali; Walter, Mariana (2010). "Conflict in Campania: Waste emergency or crisis of democracy". Ecological Economics. 70 (2): 239–249.

^ Loewe, Peter (2007-04-07). "Här tvättar maffian sina knarkpengar". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier AB. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

^ "BBC News - Naples rally against mafia's toxic waste dumping". Bbc.co.uk. 2013-11-17. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

^ "Says Politicians Hire The Camorra; Capt. Fabroni Declares Nobody Can Be Elected in Naples Without Its Aid" (pdf). The New York Times. July 13, 1911. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Behan, The Camorra, p. 24

^ "CAMORRA: processo Cuocolo". Museo criminologico. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Behan, The Camorra, p. 114

^ abc Owen, Richard (November 1, 2006). "Analysis: Naples, a city in the grip of the Camorra". The Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008.

^ Behan, The Camorra, p. 129

^ "Sub-committee onpo East-West Economic Co-operation and Convergence and Sub-committee on Civilian Security and Co-operation Trip Report: Visit to Rome / Palermo Secretariat Report 6–8 May 1998 (Prefect Gennaro Monaco, Deputy-Chief of Police and Chief of the Section of Criminal Police)". NATO Parliamentary Assembly. August 18, 1998. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

^ "Mafia 'big man' arrested". BBC News. July 11, 1998. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Pisa, Nick (December 8, 2011). "Camorra boss Michele Zagaria caught after police break into underground bunker". The Telegraph. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ "Italy Camorra mafia clan boss Mario Riccio arrested". BBC News. February 4, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Alessandra Rizzo (September 30, 2008). "Italy arrests scores of suspected mobsters". Salon.com. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

^ "Italian police arrest mafia boss at luxury hideout". theguardian.com. November 27, 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

^ "Comorra: 60 arresti tra Campania e Lombardia, anche 16 Giudici Tributari". Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). March 19, 2012. Archived from the original on August 2, 2016.

^ "Camorra: sequestrato a Milano il Gran Caffe' Sforza". Ansa (in Italian). July 4, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Trocchia, Nello (July 4, 2012). "Camorra, sequestrati beni per 20 milioni. Anche un bar in centro a Milano". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ "MAFIE AL NORD/ 'Ndrangheta, camorra e mafia: ecco come le piovre conquistano il Paese" (in Italian). Infiltrato.it. January 19, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

^ "Camorra, sotto sequestro un ristorante di Torino: tra i proprietari Cannavaro" (in Italian). Torinotoday.it. June 30, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

^ "L'ombra della Camorra in Emilia Truffa e riciclaggio: 11 indagati". Il Resto del Carlino (in Italian). March 8, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ "'Renato' è il nuovo boss della camorra in Emilia" (in Italian). Radio Città del Capo. October 22, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

^ "He insists he's just a normal businessman living quietly with his wife and children in Aberdeen. So why are Italian police so convinced Antonio la Torre is really a ruthless mafia don?". Sunday Herald. October 2, 2005. Archived from the original on March 15, 2006.

^ abcd Horne, Marc (27 January 2008). "Dons on the Don: Aberdeen revealed as the British power base for Italy's most deadly crime family". Scotland on Sunday. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

(subscription required)

^ ab Liddick, Don (2004). The Global Underworld: Transnational Crime and the United States. Greenwood. p. 34. ISBN 9780275980740.

^ Capeci, Jerry. The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia. Dorling Kindersley. p. 5. ISBN 9781436293921.

^ ab Richards, James R. (1998). Transnational Criminal Organizations, Cybercrime, and Money Laundering. CRC Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781420048728.

^ "Organized Crime: Italian Organized Crime/Mafia". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Cohen, David. "Combating Transnational Organized Crime". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

^ "la Repubblica/cronaca: Camorra, arrestato l'assassino del giornalista Siani". www.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

Sources

- Albanese, Jay S., Dilip K. Das & Arvind Verma (eds.) (2003). Organized Crime: World Perspectives. Prentice-Hall.

ISBN 9780130481993.

Behan, Tom (1996). The Camorra. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138006737.

- Dickie, John (2011). Mafia Brotherhoods: The Rise of the Italian Mafias, London: Sceptre,

ISBN 978-1-444-73430-0

- Dickie, John (2014). Blood Brotherhoods: Italy and the Rise of Three Mafias, New York: PublicAffairs,

ISBN 978-1-61039-428-4

(in Italian) Di Fiore, Gigi (1993). Potere camorrista: quattro secoli di malanapoli, Naples: Guida Editori,

ISBN 88-7188-084-6

- Liddick, Donald R. (2004). The Global Underworld: Transnational Crime and the United States. Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004,

ISBN 0-275-98074-X

- Jacquemet, Marco (1996). Credibility in Court: Communicative Practices in the Camorra Trials. Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 0-521-55251-6.

(in Italian) Paliotti, Vittorio (2006). Storia della Camorra, Rome: Newton Compton editore,

ISBN 88-541-0713-1

- Richards James R. (1998). Transnational Criminal Organizations, Cybercrime, and Money Laundering: A Handbook for Law Enforcement Officers, Auditors, and Financial Investigators, Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press, 1998.

ISBN 0-8493-2806-3. - Sales, Isaia (1993). La camorra, le camorre. Rome: Editori Riuniti.

ISBN 88-359-3710-8. (in Italian)

Further reading

- Mooney, John A. (1891). "The Two Sicilies and the Camorra". The American Catholic Quarterly Review. Vol. XVI, pp. 723–748.

- Train, Arthur (1911). "An American Lawyer at the Camorra Trial". McClure's Magazine,. Vol. XXXVIII, pp. 71–82.

- Wolffsohn, L. (1891). "Italian Secret Societies". The Contemporary Review. Vol. LIX, pp. 691–696.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camorra. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Camorra. |

Articles by Roberto Saviano published on Nazione Indiana (in Italian)

"Drug, feuds and blood in the land of the Camorra" - SCAMPIA 24 Video-documentary of the newspaper Il Mattino (in English)