Bengal Presidency

| Bengal Presidency (1757–1912) Bengal Province (1912–47) | ||||||

Presidency & province of British India | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

Capital | Calcutta | |||||

Historical era | New Imperialism | |||||

| • | Treaty of Allahabad (Battle of Buxar) | 1765 | ||||

| • | Partition of Bengal (1905) | 1905–11 | ||||

| • | Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms | 1916–21 | ||||

| • | Formation of Bengal Province (separation of Bihar and Orissa) | 1912 | ||||

| • | Partition of Bengal (1947) | 1947 | ||||

| • | Partition of India | 1947 | ||||

Today part of | ||||||

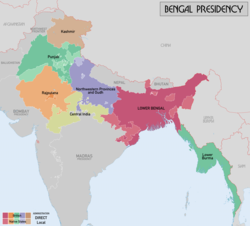

The Bengal Presidency (1757–1912), later reorganized as the Bengal Province (1912–1947), was once the largest subdivision (presidency) of British India, with its seat in Calcutta (now Kolkata). It was primarily centred in the Bengal region. At its territorial peak in the 19th century, the presidency extended from the present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan in the west to Burma, Singapore and Penang in the east. The Governor of Bengal was concurrently the Viceroy of India for many years. Most of the presidency's territories were eventually incorporated into other British Indian provinces and crown colonies. In 1905, Bengal proper was partitioned, with Eastern Bengal and Assam headquartered in Dacca and Shillong (summer capital). British India was reorganised in 1912 and the presidency was reunited into a single Bengali-speaking province.

The Bengal Presidency was established in 1765, following the defeat of the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 23 June 1757, and the Battle of Buxar in 22 October 1764. Bengal was the economic, cultural and educational hub of the British Raj. It was the centre of the late 19th and early 20th century Bengali Renaissance and a hotbed of the Indian Independence Movement.

The Partition of British India in 1947 resulted in Bengal's division on religious grounds, between the Indian state of West Bengal and East Bengal, which became the nation of Bangladesh.

Contents

1 Administrative reform and the Permanent Settlement

2 1905 Partition of Bengal

3 Reorganisation of Bengal, 1912

4 Dyarchy (1920–37)

5 Provincial Autonomy

6 See also

7 References

8 Works cited

9 External links

Administrative reform and the Permanent Settlement

British conquest after the defeat of the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757

The Victoria Memorial, Kolkata, built in honour of Queen Victoria, Empress of India

A steam engine of the Bengal Provincial Railway, 1905. Bengal was the sixth earliest region in the world to have a railway network in 1854, after Britain, the United States, Italy, France and Spain.[1]

Contemporary map from 1858

Administrative Divisions of Lower Bengal, the directly administered part of the presidency

Map showing the result of the partition of Bengal in 1905. The western part (Bengal) gained parts of Orissa, the eastern part (Eastern Bengal and Assam) regained Assam that had been made a separate province in 1874

Under Warren Hastings (British Governorships 1772–1785) the consolidation of British imperial rule over Bengal was solidified, with the conversion of a trade area into an occupied territory under a military-civil government, while the formation of a regularised system of legislation was brought in under John Shore. Acting through Lord Cornwallis, then Governor-General, he ascertained and defined the rights of the landholders over the soil. These landholders under the previous system had started, for the most part, as collectors of the revenues, and gradually acquired certain prescriptive rights as quasi-proprietors of the estates entrusted to them by the government. In 1793 Lord Cornwallis declared their rights perpetual, and gave over the land of Bengal to the previous quasi-proprietors or zamindars, on condition of the payment of a fixed land tax. This piece of legislation is known as the Permanent Settlement of the Land Revenue. It was designed to "introduce" ideas of property rights to India, and stimulate a market in land. The former aim misunderstood the nature of landholding in India, and the latter was an abject failure.

The Cornwallis Code, while defining the rights of the proprietors, failed to give adequate recognition to the rights of the under-tenants and the cultivators. This remained a serious problem for the duration of British Rule, as throughout the Bengal Presidency ryots (peasants) found themselves oppressed by rack-renting landlords, who knew that every rupee they could squeeze from their tenants over and above the fixed revenue demanded from the Government represented pure profit. Furthermore, the Permanent Settlement took no account of inflation, meaning that the value of the revenue to Government declined year by year, whilst the heavy burden on the peasantry grew no less. This was compounded in the early 19th century by compulsory schemes for the cultivation of opium and indigo, the former by the state, and the latter by British planters (most especially in Tirhut District in Bihar). Peasants were forced to grow a certain area of these crops, which were then purchased at below market rates for export. This added greatly to rural poverty.

So unsuccessful was the Permanent Settlement that it was not introduced in the North-Western Provinces (taken from the Marathas during the campaigns of Lord Lake and Arthur Wellesley) after 1831, in Punjab after its conquest in 1849, or in Oudh which was annexed in 1856. These regions were nominally part of the Bengal Presidency, but remained administratively distinct. The area of the Presidency under direct administration was sometimes referred to as Lower Bengal to distinguish it from the Presidency as a whole. Officially Punjab, Agra and Allahabad had Lieutenant-Governors subject to the authority of the Governor of Bengal in Calcutta, but in practice they were more or less independent. The only all-Presidency institutions which remained were the Bengal Army and the Civil Service. The Bengal Army was finally amalgamated into the new British-Indian Army in 1904–5, after a lengthy struggle over its reform between Lord Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief, and Lord Curzon, the Viceroy.

1905 Partition of Bengal

Eastern Bengal and Assam

Bihar and Orissa Province

A jute mill in Narayanganj, 1906. East Bengal accounted for 80% of the world's jute supply.[2]

The partition of the large province of Bengal, which was decided upon by Lord Curzon, and Cayan Uddin Ahmet, the Chief Secretary of Bengal carried into execution in October 1905. The Chittagong, Dhaka and Rajshahi divisions, the Malda District and the States of Hill Tripura, Sylhet and Comilla were transferred from Bengal to a new province, Eastern Bengal and Assam; the five Hindi-speaking states of Chota Nagpur, namely Changbhakar, Korea, Surguja, Udaipur and Jashpur State, were transferred from Bengal to the Central Provinces; and Sambalpur State and the five Oriya states of Bamra, Rairakhol, Sonepur, Patna and Kalahandi were transferred from the Central Provinces to Bengal.

The province of West Bengal then consisted of the thirty-three districts of Burdwan, Birbhum, Bankura, Midnapur, Hughli, Howrah, Twenty-four Parganas, Calcutta, Nadia, Murshidabad, Jessore, Khulna, Patna, Gaya, Shahabad, Saran, Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Darbhanga, Monghyr, Bhagalpur, Purnea, Santhal Parganas, Cuttack, Balasore, Angul and Kandhmal, Puri, Sambalpur, Singhbhum, Hazaribagh, Ranchi, Palamau, and Manbhum. The princely states of Sikkim and the tributary states of Odisha and Chhota Nagpur were not part of Bengal, but British relations with them were managed by its government.

The Indian Councils Act 1909 expanded the legislative councils of Bengal and Eastern Bengal and Assam provinces to include up to 50 nominated and elected members, in addition to three ex officio members from the executive council.[3]

Bengal's legislative council included 22 nominated members, of which not more than 17 could be officials, and two nominated experts. Of the 26 elected members, one was elected by the Corporation of Calcutta, six by municipalities, six by district boards, one by the University of Calcutta, five by landholders, four by Muslims, two by the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, and one by the Calcutta Trades Association. Eastern Bengal and Assam's legislative council included 22 nominated members, of which not more than 17 be officials and one representing Indian commerce, and two nominated experts. Of the 18 elected members, three were elected by municipalities, five by district and local boards, two by landowners, four by Muslims, two by the tea interest, one by the jute interest, and one by the Commissioners of the Port of Chittagong.[4]

The partition of Bengal proved highly controversial, as it resulted in a largely Hindu West Bengal and a largely Muslim East. Serious popular agitation followed the step, partly on the grounds that this was part of a cynical policy of divide and rule, and partly that the Bengali population, the centre of whose interests and prosperity was Calcutta, would now be divided under two governments, instead of being concentrated and numerically dominant under the one, while the bulk would be in the new division. In 1906–1909 the unrest developed to a considerable extent, requiring special attention from the Indian and Home governments, and this led to the decision being reversed in 1911.

Reorganisation of Bengal, 1912

Administrative Divisions of Province following re-organisation (Manbhum and Sylhet not included)

At the Delhi Durbar on December 12, 1911, King George V announced the transfer of the seat of the Government of India from Calcutta to Delhi, the reunification of the five predominantly Bengali-speaking divisions into a Presidency (or province) of Bengal under a Governor, the creation of a new province of Bihar and Orissa under a lieutenant-governor, and that Assam Province would be reconstituted under a chief commissioner. On March 21, 1912 Thomas Gibson-Carmichael was appointed Governor of Bengal; prior to that date the Governor-General of India had also served as governor of Bengal Presidency. On March 22, the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and Assam were constituted.[5]

The Government of India Act 1919 increased the number of nominated and elected members of the legislative council from 50 to 125, and the franchise was expanded.[6]

Bihar and Orissa became separate provinces in 1936. Bengal remained in its 1912 boundaries until Independence in 1947, when it was again partitioned between the dominions of India and Pakistan.

Dyarchy (1920–37)

British India's Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919, enacted in 1921, expanded the Bengal Legislative Council to 140 members to include more elected Indian members. The reforms also introduced the principle of dyarchy, whereby certain responsibilities such as agriculture, health, education, and local government, were transferred to elected ministers. However, the important portfolios like finance, police and irrigation were reserved with members of the Governor's Executive Council. Some of the prominent ministers were Surendranath Banerjee (Local Self-government and Public Health 1921-1923), Sir Provash Chunder Mitter (Education 1921–1924, Local Self-government, Public Health, Agriculture and Public Works 1927–1928), Nawab Saiyid Nawab Ali Chaudhuri (Agriculture and Public Works) and A. K. Fazlul Huq (Education 1924). Bhupendra Nath Bose and Sir Abdur Rahim were Executive Members in the Governor's Council.[7]

Provincial Autonomy

The Government of India Act 1935 made the Bengal Presidency into a regular province, enlarged the elected provincial legislature and expanded provincial autonomy vis a vis the central government. In the elections held in 1937, the Indian National Congress won a maximum of 54 seats but declined to form the government. The Krishak Praja Party of A. K. Fazlul Huq (with 36 seats) was able to form a coalition government along with the All-India Muslim League.[8][9]

| Minister | Portfolio |

|---|---|

A. K. Fazlul Huq | Prime Minister of Bengal, Education |

Khawaja Nazimuddin | Home |

Nalini Ranjan Sarkar | Finance |

Bijoy Prasad Singh Roy | Revenue |

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy | Commerce and Labour |

Khwaja Habibullah | Agriculture and Industry |

Srish Chandra Nandy | Irrigation, Communications and Works |

Prasanna Deb Raikut | Forest and Excise |

Mukunda Behari Mallick | Cooperative, Credit and Rural Indebtedness |

| Nawab Musharraf Hussain | Judicial and Legislature |

Syed Nausher Ali | Public Health and Local Self Government |

Huq's government fell in 1943 and a Muslim League government under Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin as Prime Minister was formed. After the end of World War II, elections were held in 1946 where the Muslim League won a majority of 113 seats out of 250 in the assembly and a government under Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was formed.[10]

| Minister | Portfolio |

|---|---|

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy | Prime Minister of Bengal, Home |

Mohammad Ali Bogra | Finance, Health, Local Self-government |

Syed Muazzemuddin Hosain | Education |

Ahmed Hossain | Agriculture, Forest and Fisheries |

Nagendra Nath Ray | Judicial and Legislative Department |

Abul Fazal Muhammad Abdur Rahman | Cooperatives and Irrigation |

Shamsuddin Ahmed | Commerce, Labour and Industries |

Abdul Gofran | Civil Supplies |

Tarak Nath Mukherjee | Irrigation and Waterways |

Fazlur Rahman | Land, Land Revenue and Jails |

Dwarka Nath Barury | Works and Building |

See also

- List of governors of Bengal

- Advocate-General of Bengal

References

^ "Railway"..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Bast and Other Plant Fibres".

^ Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1907). "Appendix II: Constitution of the Legislative Councils under the Regulations of November 1909", in The Government of India. Clarendon Press. pp. 431.

^ Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1907). "Appendix II: Constitution of the Legislative Councils under the Regulations of November 1909", in The Government of India. Clarendon Press. pp. 432–5.

^ Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1922). The Government of India, Third Edition, revised and updated. Clarendon Press. pp. 117–118.

^ Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1922). The Government of India, Third Edition, revised and updated. Clarendon Press. p. 129.

^ The Working Of Dyarchy In India 1919 1928. D.B.Taraporevala Sons And Company.

^ Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

^ Sanaullah, Muhammad (1995). A.K. Fazlul Huq: Portrait of a Leader. Homeland Press and Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9789848171004.

^ Nalanda Year-book & Who's who in India. 1946.

Works cited

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

C. A. Bayly Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (Cambridge) 1988- C. E. Buckland Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors (London) 1901

Sir James Bourdillon, The Partition of Bengal (London: Society of Arts) 1905- Susil Chaudhury From Prosperity to Decline. Eighteenth Century Bengal (Delhi) 1995

Sir William Wilson Hunter, Annals of Rural Bengal (London) 1868, and Odisha (London) 1872- P.J. Marshall Bengal, the British Bridgehead 1740–1828 (Cambridge) 1987

- Ray, Indrajit Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857) (Routledge) 2011

- John R. McLane Land and Local Kingship in eighteenth-century Bengal (Cambridge) 1993

External links

- Coins of the Bengal Presidency

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bengal Presidency. |

Coordinates: 22°33′58″N 88°20′47″E / 22.5660°N 88.3464°E / 22.5660; 88.3464