Supersolid

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

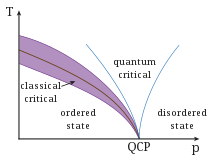

Phases · Phase transition · QCP |

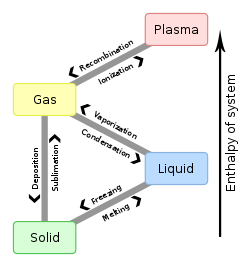

States of matter Solid · Liquid · Gas · Bose–Einstein condensate · Bose gas · Fermionic condensate · Fermi gas · Fermi liquid · Supersolid · Superfluidity · Luttinger liquid · Time crystal |

Phase phenomena Order parameter · Phase transition · QCP |

Electronic phases Electronic band structure · Plasma · Insulator · Mott insulator · Semiconductor · Semimetal · Conductor · Superconductor · Thermoelectric · Piezoelectric · Ferroelectric · Topological insulator · Spin gapless semiconductor |

Electronic phenomena Quantum Hall effect · Spin Hall effect · Kondo effect |

Magnetic phases Diamagnet · Superdiamagnet Paramagnet · Superparamagnet Ferromagnet · Antiferromagnet Metamagnet · Spin glass |

Quasiparticles Phonon · Exciton · Plasmon Polariton · Polaron · Magnon |

Soft matter Amorphous solid · Colloid · Granular material · Liquid crystal · Polymer |

Scientists Van der Waals · Onnes · von Laue · Bragg · Debye · Bloch · Onsager · Mott · Peierls · Landau · Luttinger · Anderson · Van Vleck · Mott · Hubbard · Shockley · Bardeen · Cooper · Schrieffer · Josephson · Louis Néel · Esaki · Giaever · Kohn · Kadanoff · Fisher · Wilson · von Klitzing · Binnig · Rohrer · Bednorz · Müller · Laughlin · Störmer · Tsui · Abrikosov · Ginzburg · Leggett |

A supersolid is a spatially ordered material with superfluid properties. Superfluidity is a special quantum state of matter in which a substance flows with zero viscosity.

Contents

1 Background

2 Experiments

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

Background

Liquid helium-4 was discovered by Pyotr Kapitza, John F. Allen, and Don Misener to exhibit property of superfluidity when it is cooled below a characteristic transition temperature called the lambda point. The superfluid motion of pairs of electrons (Cooper pairs) within a cooled metallic lattice is also the mechanism behind superconductivity. However, before the recent observation of superfluid-like behavior in solid helium-4,[1] superfluidity was considered to be a property exclusive to the fluid state, e.g. superconducting electron and neutron fluids, gases with Bose–Einstein condensates, or unconventional liquids such as helium-4 or helium-3 at sufficiently low temperature.

Superfluidity in helium arises from the normal liquid by a second-order phase transition ("lambda transition").

In a dilute gas of Bose particles it comes about by a phase transition that belongs to the universality class of the

spherical model. In thin liquid helium films, it arises from the normal liquid

by a Kosterlitz-Thouless transition. In the case of helium-4, it has been conjectured since 1970 that it might be possible to create a supersolid.[2]

In most theories of this state, it is supposed that vacancies, empty sites normally occupied by particles in an ideal crystal, exist even at absolute zero. These vacancies are caused by zero-point energy, which also causes them to move from site to site as waves. Because vacancies are bosons, if such clouds of vacancies can exist at very low temperature, then a Bose–Einstein condensation of vacancies could occur at temperatures less than a few tenths of a kelvin. A coherent flow of vacancies is equivalent to a "superflow" (frictionless flow) of particles in the opposite direction. Despite the presence of the gas of vacancies, the ordered structure of a crystal is maintained, although with less than one particle on each lattice site on average.

Introduction to the theory of supersolidity can be found in the textbook Superfluid States of Matter

Experiments

While several experiments yielded negative results, in the 1980s, John Goodkind from UCSD discovered the first 'anomaly' in a solid by using ultrasound.[3] Inspired by his observation, Eun-Seong Kim and Moses Chan at Pennsylvania State University saw phenomena which were interpreted as supersolid behavior.[4] Specifically, they observed what they later named Non-Classical Rotational Inertia, an unusual decoupling of the solid helium from a container's walls which could not be explained by classical models but which was consistent with a superfluid-like decoupling of a small percentage of the atoms from the rest of the atoms in the container. If such an interpretation is correct, it would signify the discovery of a new quantum phase of matter.

The experiment of Kim and Chan looked for superflow by means of a "torsional oscillator." To achieve this, a turntable is attached tightly to a spring-loaded spindle; then, instead of rotating at constant speed, the turntable is given an initial motion in one direction. The spring causes the table to oscillate similarly to a balance wheel. A toroid filled with solid helium-4 is attached to the table. The rate of oscillation of the turntable and toroid depend on the amount of solid moving with it. If there is frictionless superfluid inside, then the mass moving with the doughnut is less, and the oscillation will occur at a faster rate. In this way, one can measure the amount of superfluid existing at various temperatures. Kim and Chan found that up to about 2% of the material in the doughnut was superfluid. (Recent experiments have increased the percentage to over 20%). Similar experiments in other laboratories have confirmed these results.[3] A mysterious feature, not in agreement with the old theories, is that the transition continues to occur at high pressures.

High-precision measurements of the melting pressure of helium-4 have not resulted in any observation of a phase transition in the solid.[5]

Prior to 2007, many theorists performed calculations indicating that vacancies cannot exist at zero temperature in solid helium-4. While there is some debate, it seems more doubtful that what the experiments observed was the supersolid state.[3] Indeed, further experimentation, including that by Kim and Chan, has also cast some doubt on the existence of a true supersolid. One experiment found that repeated warming followed by slow cooling of the sample causes the effect to disappear. This annealing process removes flaws in the crystal structure. Furthermore, most samples of helium-4 contain a small amount of helium-3. When some of this helium-3 is removed, the superfluid transition occurs at a lower temperature, which suggests that the superflow is involved with actual fluid moving along imperfections in the crystal rather than a property of the perfect crystal.

In 2009, it was proposed to realize a supersolid in an optical lattice.

Starting from a molecular quantum crystal, supersolidity is induced dynamically as an out-of-equilibrium state. While neighboring molecular wave functions overlap, two bosonic species simultaneously exhibit quasicondensation and long-range solid order, which is stabilized by their mass imbalance. This proposal can be realized[6] in present experiments with bosonic mixtures in an optical lattice that features simple on-site interactions.

Experimental and theoretical work continues in hopes of finally settling the question of the existence of a supersolid.

In 2012, Chan repeated his original experiments with a new apparatus that was designed to eliminate any contribution from elasticity of the helium. In this experiment, Chan and his coauthors found no evidence of supersolidity.[7]

In 2017, two research groups from ETH Zurich and from MIT reported on the first creation of a supersolid with ultracold quantum gases. The Zurich group placed a Bose-Einstein condensate inside two optical resonators, which enhanced the atomic interactions until they start to spontaneously crystallize and form a solid that maintains the inherent superfluidity of Bose-Einstein condensates.[8][9] The MIT group exposed a Bose-Einstein condensate in a double-well potential to light beams that created an effective spin-orbit coupling. The interference between the atoms on the two spin-orbit coupled lattice sites gave rise to a density modulation that establishes a stripe phase with supersolid properties.[10][11]

See also

- Superfluid film

- Superglass

References

^ Ball, Philip (15 January 2004). "Glimpse of a new type of matter". Nature. doi:10.1038/news040112-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Chester, G. V. (1970). "Speculations on Bose-Einstein Condensation and Quantum Crystals". Physical Review A. 2 (1): 256–258. Bibcode:1970PhRvA...2..256C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.2.256.

^ abc Chalmers, Matthew (2007-05-01). "The quantum solid that defies expectation". Physics World. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

^ Kim, E.; Chan, M. H. W. (2004). "Probable Observation of a Supersolid Helium Phase". Nature. 427 (6971): 225–227. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..225K. doi:10.1038/nature02220. PMID 14724632.

^ Todoshchenko, I. A.; Alles, H.; Junes, H. J.; Parshin, A. Ya.; Tsepelin, V. (2007). "Absence of low-temperature anomaly on the melting curve of 4He" (PDF). JETP Letters. 85 (9): 555–558. arXiv:cond-mat/0703743. Bibcode:2007JETPL..85..454T. doi:10.1134/S0021364007090093.

^ Keilmann, Tassilo; Cirac, Ignacio; Roscilde, Tommaso (2009). "Dynamical Creation of a Supersolid in Asymmetric Mixtures of Bosons". Physical Review Letters. 102 (25): 255304. arXiv:0906.1110. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102y5304K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.255304. PMID 19659092.

^ Voss, David (2012-10-08). "Focus: Supersolid Discoverer's New Experiments Show No Supersolid". Physics. 5: 111. Bibcode:2012PhyOJ...5..111V. doi:10.1103/physics.5.111.

^ Würsten, Felix (1 March 2017). "Crystalline and liquid at the same time". ETH Zurich. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

^ Léonard, Julian; Morales, Andrea; Zupancic, Philip; Esslinger, Tilman; Donner, Tobias (1 March 2017). "Supersolid formation in a quantum gas breaking a continuous translational symmetry". Nature. 543 (7643): 87–90. arXiv:1609.09053. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...87L. doi:10.1038/nature21067. PMID 28252072. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

^ Keller, Julia C. (March 2, 2017). "MIT researchers create new form of matter". MIT News. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

^ Li, Jun-Ru; Lee, Jeongwon; Huang, Wujie; Burchesky, Sean; Shteynas, Boris; Top, Furkan Çağrı; Jamison, Alan O.; Ketterle, Wolfgang (1 March 2017). "A stripe phase with supersolid properties in spin–orbit-coupled Bose–Einstein condensates". Nature. 543 (7643): 91–94. arXiv:1610.08194. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...91L. doi:10.1038/nature21431. PMID 28252062. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

External links

Nature story on a supersolid experiment (Premium Link)- Penn State: What is a Supersolid?

- Phys. Rev. Lett. Vol.101, 8 August 2008

- (1969). "Destruction of Superflow in Unsaturated 4He Films and the Prediction of a New Crystalline Phase of 4He with Bose–Einstein Condensation", Physics Letters, Vol. 30, No. 5, November 3, 1969, pp. 300–301 Jack Sarfatti

- Youtube lecture on Supersolids