Decidualization

| Decidual reaction | |

|---|---|

Sectional plan of the gravid uterus in the third and fourth month. | |

Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] |

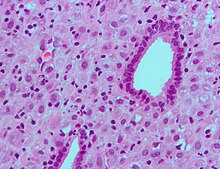

Micrograph showing decidualization of the endometrium due to exogenous progesterone (oral contraceptive pill). H&E stain.

Decidualization is a process that results in significant changes to cells of the endometrium in preparation for, and during, pregnancy. This includes morphological and functional changes (the decidual reaction) to endometrial stromal cells (ESCs), the presence of decidual white blood cells (leukocytes), and vascular changes to maternal arteries. The sum of these changes results in the endometrium changing into a structure called the decidua. In humans, the decidua is shed during the third phase of birth.[1]

Decidualization plays an important role in promoting placenta formation between a mother and her fetus by mediating the invasiveness of trophoblast cells. It also triggers the production of cellular and molecular factors that result in structural changes, or remodeling, of maternal spiral arteries. Decidualization is required in some mammalian species where embryo implantation and trophoblast cell invasion of the endometrium occurs, also known as hemochorial placentation. This allows maternal blood to come into direct contact with the fetal chorion, a membrane between the fetal and maternal tissues, and allows for nutrient and gas exchange. However, decidualization-like reactions have also been observed in some species that don't display hemochorial placentation.[2]

In humans, decidualization occurs after ovulation during the menstrual cycle. After implantation of the embryo, the decidua further develops to mediate the process of placentation. In the event no embryo is implanted, the decidualized endometrial lining is shed or, as is the case with species that follow the estrous cycle, absorbed.[1] In menstruating species, decidualization is spontaneous and occurs as a result of maternal hormones. In non-menstruating species, decidualization is non-spontaneous, meaning it only happens after there external signals from an implanted embryo.[3]

Contents

1 Overview

1.1 Decidual leukocytes

1.2 Endometrial stromal cells (ESCs)

2 During pregnancy

3 Role in diseases and disorders

4 In research

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Overview

After ovulation, the high levels of progesterone initiate the molecular changes leading to decidualization. The process triggers an influx of decidual leukocytes along with morphological and functional changes of ESCs. The changes in the ESCs result in the endometrium developing a secretory lining that produces a variety of proteins, cytokines, and growth factors. These secreted factors will regulate the invasiveness of trophoblast cells that eventually form the placental connection if an embryo implants into the decidua.[4]

Decidual leukocytes

One of the identifying features of the decidua is the presence of large numbers of leukocytes that are mostly made up of specialized uterine natural killer (uNK) cells[5] and some dendritic cells. As the fetus consists of both maternal and paternal DNA, the decidual leukocytes play a role in suppressing the immune response of the mother to prevent treating the fetus as genetically foreign. Outside of their immune functions, the uNK cells and dendritic cells also act as regulators of maternal spiral artery remodeling and ESC differentiation.[6]

Endometrial stromal cells (ESCs)

ESCs are the connective tissue cells of the endometrium that are fibroblastic in appearance. However, decidualization causes them to swell up and adopt an epithelial cell-like appearance due to the accumulation of glycogen and lipid droplets. Furthermore, they begin secreting cytokines, growth factors, and proteins like IGFBP1 and prolactin, along with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as fibronectin and laminin. The increased production of these ECM proteins turns the endometrium into the dense structure known as the decidua, which produces factors that promote trophoblast attachment and inhibit overly aggressive invasion.[7]

During pregnancy

The decidual reaction is seen in very early pregnancy in the generalized area where the blastocyst contacts the endometrial decidua. It consists of an increase in secretory functions of the endometrium at the area of implantation, as well as a surrounding stroma that becomes edematous.[8]

The decidual reaction occurs only in a few species such as humans. The decidual reaction and decidua are not required for implantation. Evidence can be taken from the fact that in ectopic pregnancy, implantation can occur anywhere in the abdominal cavity. Even after hysterectomy some women have become pregnant.[9]

Role in diseases and disorders

Abnormalities in decidualization have been implicated in diseases such as endometriosis, in which impaired decidualization leads to ectopic uterine tissue growth. Lack of decidualization has also been linked to higher rates of miscarriage.[10]

Chronic deciduitis, a chronic inflammation of the decidua, has been linked with premature birth.[11]

In research

The decidualization process is initiated by progesterone, but this requires cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) to act as the initial signalling molecule to sensitize endometrial cells to progesterone. Consequently, human ESCs have been decidualized in culture with chemical analogs of cAMP and progesterone together. In vitro decidualization results in similar morphological changes to the human ESCs as well as upregulated production of decidualization markers such as IGFBP1 and prolactin.[7]

Mouse models have been extensively used for the identification of the molecular factors required for and involved in decidualization.[12]

See also

- Decidua

- Decidual cells

- Decidual reaction

References

^ ab Pansky, Ben (1982-08-01). Review of Medical Embryology. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071053037..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Kurjak, Asim; Chervenak, Frank A. (2006-09-25). Textbook of Perinatal Medicine, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 9781439814697.

^ Emera, Deena; Romero, Roberto; Wagner, Günter (2011-11-07). "The evolution of menstruation: A new model for genetic assimilation". BioEssays. 34 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/bies.201100099. ISSN 0265-9247. PMC 3528014. PMID 22057551.

^ Brosens, Jan J.; Pijnenborg, Robert; Brosens, Ivo A. (November 2002). "The myometrial junctional zone spiral arteries in normal and abnormal pregnancies". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 187 (5): 1416–1423. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.127305.

^ Lash, G.E.; Robson, S.C.; Bulmer, J.N. (March 2010). "Review: Functional role of uterine natural killer (uNK) cells in human early pregnancy decidua". Placenta. 31: S87–S92. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.022. PMID 20061017.

^ Blois, Sandra M.; Klapp, Burghard F.; Barrientos, Gabriela (2011). "Decidualization and angiogenesis in early pregnancy: unravelling the functions of DC and NK cells". Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 88 (2): 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2010.11.002. PMID 21227511.

^ ab Gellersen, Birgit; Brosens, Ivo; Brosens, Jan (2007-11-01). "Decidualization of the Human Endometrium: Mechanisms, Functions, and Clinical Perspectives". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 25 (6): 445–453. doi:10.1055/s-2007-991042. ISSN 1526-8004. PMID 17960529.

^ T. F. Kruger, M. H. Botha. Clinical Gynaecology; page 67. Juta Academic; 3rd edition (September 5, 2008).

ISBN 0702173053

^ Nordqvist, Christian (29 May 2011). "Baby Who Developed Outside The Womb Is Born". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

^ Gellersen, Birgit; Brosens, Jan J. (2014-08-20). "Cyclic Decidualization of the Human Endometrium in Reproductive Health and Failure". Endocrine Reviews. 35 (6): 851–905. doi:10.1210/er.2014-1045. ISSN 0163-769X. PMID 25141152.

^ Edmondson, Nadeen; Bocking, Alan; Machin, Geoffrey; Rizek, Rose; Watson, Carole; Keating, Sarah (2008-01-02). "The Prevalence of Chronic Deciduitis in Cases of Preterm Labor without Clinical Chorioamnionitis". Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 12 (1): 16–21. doi:10.2350/07-04-0270.1. ISSN 1093-5266. PMID 18171100.

^ Ramathal, Cyril; Bagchi, Indrani; Taylor, Robert; Bagchi, Milan (2010-01-01). "Endometrial Decidualization: Of Mice and Men". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 28 (1): 017–026. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242989. ISSN 1526-8004. PMC 3095443. PMID 20104425.

External links

Implantation stages Human embryology; developed by the universities of Fribourg, Lausanne and Bern (Switzerland).

Histopathology Uterus – Decidual reaction Microscopic review of decidualization