Abraham Kuyper

His Excellency the Reverend Abraham Kuyper | |

|---|---|

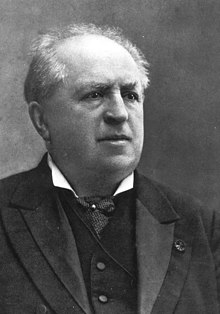

Kuyper in 1905 | |

| Prime Minister of the Netherlands | |

In office 1 August 1901 – 17 August 1905 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelmina |

| Preceded by | Nicolaas Pierson |

| Succeeded by | Theo de Meester |

| Member of the Senate | |

In office 16 September 1913 – 22 September 1920 | |

| Parliamentary group | Anti-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of the Interior | |

In office 1 August 1901 – 17 August 1905 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Hendrik Goeman Borgesius |

| Succeeded by | Pieter Rink |

Parliamentary leader in the House of Representatives | |

In office 13 November 1908 – 18 September 1912 | |

| Preceded by | Jan Hendrik de Waal Malefijt |

| Succeeded by | Gerrit Middelberg |

In office 16 September 1896 – 1 August 1901 | |

| Preceded by | Jan van Alphen |

| Succeeded by | Jan van Alphen |

In office 20 May 1894 – 1 July 1894 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Jan van Alphen |

| Parliamentary group | Anti-Revolutionary Party |

| Leader of the Anti-Revolutionary Party | |

In office 3 April 1879 – 31 March 1920 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Hendrikus Colijn |

| Chairman of the Anti-Revolutionary Party | |

In office 12 February 1907 – 31 March 1920 | |

| Leader | Himself |

| Preceded by | Herman Bavinck |

| Succeeded by | Hendrikus Colijn |

In office 3 April 1879 – 17 August 1905 | |

| Leader | Himself |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Herman Bavinck |

| Member of the House of Representatives | |

In office 13 November 1908 – 18 September 1912 | |

In office 16 May 1894 – 31 July 1901 | |

In office 20 March 1874 – 1 June 1877 | |

| Parliamentary group | Anti-Revolutionary Party (1894–1912) Independent Protestant (1874–1877) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abraham Kuijper (1837-10-29)29 October 1837 Maassluis, Netherlands |

| Died | 8 November 1920(1920-11-08) (aged 83) The Hague, Netherlands |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Political party | Anti-Revolutionary Party (from 1879) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent Protestant (1874–1877) |

| Spouse(s) | Johanna Hendrika Schaay (m. 1863; died 1899) |

| Children | Herman Kuyper (1864–1945) Jan Kuyper (1866–1933) Henriëtte Kuyper (1870–1933) Abraham Kuyper Jr. (1872–1941) Johanna Kuyper (1875–1948) Catharina Kuyper (1876–1955) Guillaume Kuyper (1878–1941) Levinus Kuyper (1882–1892) |

| Alma mater | Leiden University (Bachelor of Theology, Master of Theology, Doctor of Theology, Doctor of Philosophy) |

| Occupation | Politician · Minister · Theologian · Historian · Journalist · Author · Academic administrator · Professor |

| Signature | |

Abraham Kuijper (/ˈkaɪpər/; Dutch: [ˈaːbraːɦɑm ˈkœypər]; 29 October 1837 – 8 November 1920), publicly known as Abraham Kuyper, was Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1901 and 1905, an influential neo-Calvinist theologian and also a journalist. He established the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, which upon its foundation became the second largest Reformed denomination in the country behind the state-supported Dutch Reformed Church.

In addition, he founded a newspaper, the Free University of Amsterdam and the Anti-Revolutionary Party. In religious affairs, he sought to adapt the Dutch Reformed Church to challenges posed by the loss of state financial aid and by increasing religious pluralism in the wake of splits that the church had undergone in the 19th century, rising Dutch nationalism, and the Arminian religious revivals of his day which denied predestination.[1] He vigorously denounced modernism in theology as a fad that would pass away. In politics, he dominated the Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) from its founding in 1879 to his death in 1920. He promoted pillarisation, the social expression of the anti-thesis in public life, whereby Protestant, Catholic and secular elements each had their own independent schools, universities and social organisations.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Religious life

2.1 Doleantie

2.2 Anti-modernism

3 Political life

3.1 Member of Parliament

3.2 Prime minister

3.3 Minister of State

4 Views

4.1 Theological views

4.2 Political views

5 Legacy

6 Bibliography

7 Notes and references

8 Further reading

9 External links

Early life

Abraham Kuijper was born on 29 October 1837 in Maassluis, Netherlands. His father Jan Frederik Kuyper served as a minister for the Dutch Reformed Church in Hoogmade, Maassluis, Middelburg and Leiden.

Kuijper was home-schooled by his father. The boy received no formal primary education, but received secondary education at the Gymnasium of Leiden. In 1855, he graduated from the Gymnasium and began to study literature, philosophy and theology at Leiden University. He received his propaedeuse in literature in 1857, summa cum laude, and in philosophy in 1858, also summa cum laude. He also took classes in Arabic, Armenian and physics.

In 1862 he was promoted to Doctor in theology on the basis of a dissertation entitled "Disquisitio historico-theologica, exhibens Johannis Calvini et Johannis à Lasco de Ecclesia Sententiarum inter se compositionem" (Theological-historical dissertation showing the differences in the rules of the church, between John Calvin and John Łaski). In comparing the views of John Calvin and Jan Łaski, Kuyper showed a clear sympathy for the more liberal Łaski. During his studies Kuyper was a member of the modern tendency within the Dutch Reformed Church.

Religious life

In May 1862, he was declared eligible for the ministry and 1863 he accepted a call to become minister for the Dutch Reformed Church for the town of Beesd. In the same year he married Johanna Hendrika Schaay (1842–1899). They would have five sons and three daughters. In 1864 he began corresponding with the anti-revolutionary MP Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer, who heavily influenced his political and theological views (see below).

Around 1866, he began to sympathise with the orthodox tendency within the Dutch Reformed Church. He was inspired by the robust reformed faith of Pietje Balthus, a single woman in her early 30s, the daughter of a miller.[2] He began to oppose the centralization in the church, the role of the King and began to plead for the separation of church and state.

In 1867, Kuyper was asked to become minister for the parish in Utrecht and he left Beesd. In 1870 he was asked to come to Amsterdam. In 1871 he began to write for the De Heraut (The Herald).

In 1872, he founded his own paper, De Standaard (The Standard). This paper would lay the foundation for the network of Reformed organisation, (the Reformed pillar), which Kuyper would found.

Doleantie

In 1886, Kuyper led an exodus from the Dutch Reformed Church. He grieved the loss of Reformed distinctives within this State Church, which no longer required office bearers to agree to the Reformed standards which had once been foundational.[3]

Kuyper and the consistory of Amsterdam insisted that both ministers and church members subscribe to the Reformed confessions. This was appealed to Classis, and Kuyper, along with about 80 members of the Amsterdam consistory, were suspended in Dec. 1885. This was appealed to the provincial synod, which upheld the ruling in a 1 July 1886 ruling.[3]

Refusing to accept his suspension, Kuyper preached to his followers in an auditorium on Sunday, 11 July 1886. Because of their deep sorrow at the state of the Dutch Reformed Church, the group called itself the Doleantie (grieving ones).

By 1889, the Doleantie churches had over 200 congregations, 180,000 members, and about 80 ministers.

Kuyper, (although at first antagonistic towards them), soon began to seek union with the churches of the Secession of 1834, the Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken (Christian Reformed Church). These churches had earlier broken off from the Dutch Reformed Church. This union was effected in 1892, and the Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (Reformed Churches in the Netherlands) was formed. This denomination has its counterpart in the Christian Reformed Church in North America.

Anti-modernism

He vigorously ridiculed modernism in theology as a new-fangled fad based on a superficial view of reality. He argued that modernism missed the reality of God, of prayer, of sin, and of the church. He said modernism would eventually prove as useless as 'A Squeezed Out Lemon Peel,' while traditional religious truths would survive.[4] In his lectures at Princeton in 1898 he argued that Calvinism was more than theology—it provided a comprehensive worldview and indeed had already proven to be a major positive factor in the development of the institutions and values of modern society.[5]

Political life

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

Organizations

|

Ideas

|

Documents

|

People

|

|

Member of Parliament

In 1873, Kuyper stood as candidate in the general election for parliament for the constituency of Gouda, but he was defeated by the incumbent member of parliament, the conservative Jonkheer Willem Maurits de Brauw. When De Brauw died the next year, Kuyper stood again in the by-election for the same district. This time he was elected to parliament, defeating the liberal candidate Herman Verners van der Loeff.

Kuyper subsequently moved to The Hague, without telling his friends in Amsterdam. In parliament he showed a particular interest in education, especially the equal financing of public and religious schools. In 1876, he wrote "Our Program" which laid the foundation for the Anti-Revolutionary Party. In this programme he formulated the principle of antithesis, the conflict between the religious (Reformed and Catholics) and non-religious. In 1877, he left parliament because of problems with his health, suffering from overexertion.

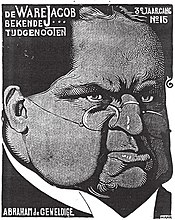

In 1878, Kuyper returned to politics, he led the petition against a new law on education, which would further disadvantage religious schools. This was an important impetus for the foundation of the Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) in 1879, of which Kuyper would be chairman between 1879 and 1905. He would be the undisputed leader of the party between 1879 and 1920. His followers gave him the nickname "Abraham de Geweldige" (Abraham the Great). In 1880, he founded the Free University in Amsterdam and he was made professor of Theology there. He also served as its first rector magnificus. In 1881, he also became professor of literature. In 1886, he left the Dutch Reformed Church, with a large group of followers. The parish in Amsterdam was made independent of the church, and kept their own building. Between 1886 and 1892, they would be called the Dolerenden, (those with grievances). In 1892, those Dolerenden founded a new denomination called The Reformed Churches in the Netherlands after merging with other orthodox Reformed people who had seceded from the Dutch Reformed Church in 1834.

In the general election of 1894, Kuyper was re-elected to the House of Representatives for the district of Sliedrecht. He defeated the liberal Van Haaften and the anti-takkian anti-revolutionary Beelaerts van Blokland. He also ran as a candidate in Dordrecht and Amsterdam, but was defeated there. In the election he joined the so-called Takkians, in a conflict between the liberal minister Tak, and a majority House of Representatives. Tak wanted to reform the census-suffrage, but a majority in parliament rejected his proposal. Kuyper favoured the legislation because he expected the enfranchised lower class voters would favour his party. This orientation towards the lower classes gave him the nickname "The bellringer of the common people" (klokkeluider van de kleine luyden). His position on suffrage also led to a conflict within the ARP: a group around Alexander de Savornin Lohman was opposed on principle to universal suffrage because they rejected popular sovereignty; they left the ARP to found the CHU in 1901. The authoritarian leadership of Kuyper also played an important role in this conflict. Lohman opposed party discipline and wanted MPs to make up their own mind, while Kuyper favoured strong leadership. After the elections Kuyper became chair of the parliamentary caucus of the ARP. In his second term as MP he concentrated on more issues than education, like suffrage, labour, and foreign policy. In foreign affairs especially the Second Boer War was of particular interest to him, in the conflict between the Dutch-speaking reformed farmers and the English-speaking Anglicans he sided with the Boers, and heavily opposed the English. In 1896, Kuyper voted against the new suffrage law of Van Houten, because according to Kuyper the reforms did not go far enough. In the 1897 elections, Kuyper competed in Zuidhorn, Sliedrecht and Amsterdam. He was defeated by liberals in Zuidhorn and Amsterdam, but he defeated the liberal Wisboom in Sliedrecht. In Amsterdam he was defeated by Johannes Tak van Poortvliet. As an MP, Kuyper kept his job as journalist, and he even became chair of the Dutch Circle of Journalists in 1898; when he left in 1901 he was made honorary president. In the same year, at the invitation of B.B. Warfield, Kuyper delivered the Stone Lectures at Princeton Seminary, which was his first widespread exposure to a North American audience. These lectures were given 10–11 October 14 and 19–21 in 1898. He also received an honorary doctorate in law there. During his time in the United States, he also traveled to address several Dutch Reformed congregations in Michigan and Iowa and Presbyterian gatherings in Ohio and New Jersey.

Prime minister

Caricature of Kuyper by Albert Hahn, from a 1904 edition of the satirical magazine De Ware Jacob.

In the 1901 elections, Kuyper was re-elected in Sliedrecht, defeating the liberal De Klerk. In Amsterdam he was defeated again, now by the freethinking liberal Nolting. He did not take his seat in parliament however but was instead appointed formateur and later prime minister of the Dutch cabinet. He also served as minister of Home Affairs. He originally wanted to become minister of labour and enterprise, but neither Mackay or Heemskerk, prominent anti-revolutionaries, wanted to become minister of Home Affairs, forcing him to take the portfolio. During his time as prime minister he showed a strong leadership style: he changed the rules of procedure of cabinet in order to become chair of cabinet for four years (before him, the chairmanship of the cabinet had rotated among its members).

The portfolio of home affairs at the time was very broad: it involved local government, industrial relations, education and public morality. The 1903 railway strike was one of the decisive issues for his cabinet. Kuyper produced several particularly harsh laws to end the strikes (the so-called "worgwetten", strangling laws), and pushed them through parliament. He also proposed legislation to improve working conditions; however only those on fishing and harbour construction passed through parliament. In education Kuyper changed several education laws to improve the financial situation of religious schools. His law on higher education, which would make the diplomas of faith-based universities equal to that of the public universities, was defeated in the Senate. Consequently, Kuyper dissolved the Senate and, after a new one was elected, the legislation was accepted. He was also heavily involved in foreign policy, giving him the nickname "Minister of Foreign Travels".

Minister of State

In 1905, his ARP lost the elections and was confined to opposition. Between 1905 and 1907, Kuyper made a grand tour around the Mediterranean. In 1907, Kuyper became honorary doctor at the Delft University of Technology. In 1907, he was re-elected chair of the ARP, a post which he would hold to his death in 1920. In 1907, Kuyper wanted to return to parliament. In a by-election in Sneek he needed the support of the local CHU. They refused him support. This led to a personal conflict between Kuyper and De Savorin Lohman. In 1908, he came into conflict with Heemskerk, who had not involved him in the formation of the CHU/ARP/Catholic General League cabinet, thereby denying him the chance to return as minister. In 1908, Kuyper received the honorary title of minister of state. He was elected to the House of Representatives for the district of Ommen in the by-elections in the same year, defeating the liberal De Meester. He also ran in Sneek where he was elected as sole candidate. Kuyper took the seat for Ommen. In 1909, he was made chair of the committee which would write the new orthography of the Dutch language. In the same year he also received an honorary doctorate at the Catholic University of Leuven. In the 1909 elections he was re-elected in Ommen, defeating the liberal Teesselink, but he was defeated in Dordrecht by the liberal De Kanter.

In 1909, he came under heavy criticism in the so-called decorations affairs (lintjeszaak). While minister of home affairs, Kuyper allegedly received money from one Rudolf Lehman, to make him Officer in the Order of Orange-Nassau. A parliamentary debate was held on the subject and a committee was instituted to research the claim. In 1910, the committee reported that Kuyper was innocent. Between 1910 and 1912, he was member of the committee headed by Heemskerk, which prepared a revision of the constitution. In 1912, he resigned his seat in parliament for health reasons, but he returned to politics in the following year, this time as a member of the Senate for the province of South Holland. He would retain this seat until his death. In 1913, he was made commander in the Order of the Netherlands Lion. During the First World War Kuyper sided with the Germans, because he had opposed the English since the Boer wars. In 1918, Kuyper played an important role in the formation of the first cabinet led by Charles Ruijs de Beerenbrouck. In 1920, at the age of 83 Kuyper died in The Hague and was buried amid great public attention.

Views

Kuyper's theological and political views are linked. His orthodox Protestant beliefs heavily influenced his anti-revolutionary politics.

Theological views

In 1905 there was a higher education law enacted, but Kuyper was against this and became part of the opposition.

Theologically Kuyper has also been very influential. He opposed the liberal tendencies within the Dutch Reformed Church. This eventually led to secession and the foundation of Reformed Churches in the Netherlands. He developed so-called Neo-Calvinism, which goes beyond conventional Calvinism on a number of issues. Furthermore, Kuyper made a significant contribution to the formulation of the principle of common grace in the context of a Reformed world-view.

Most important has been Kuyper's view on the role of God in everyday life. He believed that God continually influenced the life of believers, and daily events could show his workings. Kuyper famously said, "Oh, no single piece of our mental world is to be hermetically sealed off from the rest, and there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: 'Mine!'"[6][7] God continually re-creates the universe through acts of grace. God's acts are necessary to ensure the continued existence of creation. Without his direct activity creation would self-destruct."

Political views

Kuyper's political ideals were orthodox-Protestant and anti-revolutionary.

The concept of sphere sovereignty was very important for Kuyper. He rejected the popular sovereignty of France in which all rights originated with the individual, and the state-sovereignty of Germany in which all rights derived from the state. Instead, he wanted to honour the "intermediate bodies" in society, such as schools and universities, the press, business and industry, the arts etc., each of which would be sovereign in its own sphere. In the interest of a level playing field, he championed the right of every faith community (among whom he counted humanists and socialists) to operate their own schools, newspapers, hospitals, youth movements etc. He sought equal government finances for all faith-based institutions. He saw an important role for the state in upholding the morality of the Dutch people. He favoured monarchy, and saw the House of Orange as historically and religiously linked to the Dutch people. His commitment to universal suffrage was only tactical;[inconsistent] he expected the Anti-Revolutionary Party would be able to gain more seats this way. In actuality, Kuyper wanted a Householder Franchise where fathers of each family would vote for his family.[citation needed] He also favoured a Senate representing the various interest, vocational and professional groups in society.

With his ideals, he defended the interests of a group of middle class orthodox reformed, who were often referred to as "the little people" (de kleine luyden). He formulated the principle of antithesis: a divide between secular and religious politics. Liberals and socialists, who were opposed to mixing religion and politics were his natural opponents. Catholics were a natural ally, for not only did they want to practice religiously inspired politics, but they also were no electoral opponent, because they appealed to different religious groups. Socialists, who preached class conflict were a danger to the reformed workers. He called for workers to accept their fates and be happy with a simple life because the afterlife would be much more satisfying and revolution would only lead to instability. At the same time, he argued that the system of unrestricted free enterprise was in need of "architectonic critique" and he urged government to adopt labour legislation and to inspect workplaces.

Legacy

Kuyper's political views and acts have influenced Dutch politics. Kuyper stood at the cradle of pillarisation, the social expression of the anti-thesis in public life. His championing of parity treatment for faith-based organisations and institutions created the basis for the alliance between Protestants and Catholics that would dominate Dutch politics to the present day. One of the major political parties of the Netherlands, the CDA, is still heavily influenced by Kuyper's thought. His greatest theological act, the founding of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands was undone in 2005 with the creation of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands which united the Dutch Reformed Church, the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

In North America, Kuyper's political and theological views have had a significant impact, especially in the Reformed community. He is considered the father of Dutch Neo-Calvinism and had considerable influence on the thought of philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd. Others that have been influenced by Kuyper include Auguste Lecerf, Francis Schaeffer, Cornelius Van Til, Alvin Plantinga, Nicholas Wolterstorff, Albert M. Wolters, Vincent Bacote, Anthony Bradley, Chuck Colson, Timothy J. Keller, James Skillen, R Tudur Jones, Bobi Jones, and the hip hop artist Lecrae.

Institutions influenced by Kuyper include Cardus (formerly The Work Research Foundation), Calvin College, The Clapham Institute, Dordt College, Institute for Christian Studies, Redeemer University College, The Coalition for Christian Outreach, Covenant College, The Center for Public Justice, and the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, & Culture. In 2006, Reformed Bible College, located in Grand Rapids, Michigan was renamed in honor of Abraham Kuyper and is now Kuyper College.

As well as Kuyper's profound influence upon European Christian-Democrat politics up to the present, his political theology was also crucial in the history of South Africa. His legacy in South Africa is arguably even greater than within the Netherlands. There, his Christian-National conception, centred upon the identification of the Afrikaner Calvinist community as the kern der natie became a rallying position for the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk. As Christian-Nationalists, Kuyper's adherents in South Africa were instrumental in the building of Afrikaner cultural, political and economic institutions to restore Afrikaner fortunes following the Boer War, which ultimately led to Apartheid.[8]

Saul Dubow notes that Kuyper advocated "the commingling of blood" as "the physical basis for all higher development" in the Stone Lectures (1898). Harinck argues that "Kuyper was not guided by the cultural racism of his day, but by his Calvinistic creed of human equality".[9]

Kuyper's legacy includes a granddaughter, Johtje Vos, who is noted for having sheltered many Jews in her home in the Netherlands from the Nazis. After World War II she moved to New York City.[10] Conversely, Kuyper's son Professor H. H. Kuyper, a supporter of Afrikaner Nationalism and colour racism, was a wartime Nazi collaborator and his grandson joined the Waffen SS and died on the Russian front.

Bibliography

Kuyper wrote several theological and political books:

Disquisitio historico-theologica, exhibens Johannis Calvini et Johannis à Lasco de Ecclesia Sententiarum inter se compositionem (Theological-historical dissertation showing the differences in the rules of the church, between John Calvin and John Łaski; his dissertation, 1862)

Conservatisme en Orthodoxie (Conservatism and Orthodoxy; 1870)

Het Calvinisme, oorsprong en waarborg onzer constitutionele vrijheden. Een nederlandse gedachte (Calvinism; the source and the safeguard of our constitutional freedoms. A Dutch thought; 1874)

Ons Program (Our program; ARP political program, 1879)

Antirevolutionair óók in uw huisgezin (Anti-revolutionary in your family too; 1880)

Soevereiniteit in eigen kring (Sovereignty in its own circle; 1880)

Handenarbeid (1889; Manual Labour)

Maranatha (1891)

Het sociale vraagstuk en de Christelijke Religie (The Social Question and the Christian Religion; 1891)

Encyclopaedie der Heilige Godgeleerdheid (Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology; 1893–1895)

Calvinisme (Lectures on Calvinism; six Stone lectures Kuyper held at Princeton in 1898)- The South African Crisis (1900)

De Gemene Gratie (Common Grace; 1902–1905)

Parlementaire Redevoeringen (parliamentary speeches; 1908–1910)

Starrentritsen (1915)

Antirevolutionaire Staatkunde (Anti-revolutionary politics; 1916–1917)

Vrouwen uit de Heilige schrift (Women from the Holy scripture; 1897)

Notes and references

- Notes

^ Wood 2013.

^ Mouw 2011, p. 3.

^ ab "Dr. Abraham Kuyper". Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-06.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link).mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Molendijk 2011.

^ Molendijk 2008.

^ 1880 Inaugural Lecture, Free University of Amsterdam

^ Kuyper 1998, p. 461.

^ Bloomberg 1989, p. 12.

^ Harinck 2002, p. 187.

^ Hevesi, Dennis (4 November 2007). "Johtje Vos, Who Saved Wartime Jews, Dies at 97". New York Times.

- References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Bloomberg, Charles (1989). Christian Nationalism and the Rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa, 1918-48. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-10694-3.

Harinck, George (2002). "Abraham Kuyper, South Africa, and Apartheid". The Princeton Seminary Bulletin. 23. Archived from the original on 2012-08-28.

Kuyper, Abraham (1998). "Sphere Sovereignty". In Bratt, James D. Abraham Kuyper: A Centennial Reader. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4321-0.

Molendijk, Arie L. (2008). "Neo-Calvinist Culture Protestantism: Abraham Kuyper's Stone Lectures". Church History and Religious Culture. 88 (2): 235–250. doi:10.1163/187124108X354330. ISSN 1871-241X.

Molendijk, Arie L. (2011). ""A Squeezed Out Lemon Peel." Abraham Kuyper on Modernism". Church History and Religious Culture. 91 (3): 397–412. doi:10.1163/187124111X609397. ISSN 1871-241X.

Mouw, Richard J. (2011). Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6603-5.

Wood, John Halsey (2013). Going Dutch in the Modern Age: Abraham Kuyper's Struggle for a Free Church in the Netherlands. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992038-9.

Further reading

Bratt, James D. (2013). Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6906-7.

Kuipers, Tjitze (2011). Abraham Kuyper: An Annotated Bibliography 1857-2010. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-21139-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abraham Kuyper. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abraham Kuyper |

Works by Abraham Kuyper at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Abraham Kuyper at Internet Archive

- Digital Library of Abraham Kuyper

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

New office | Leader of the Anti-Revolutionary Party 1879–1920 | Succeeded by Hendrikus Colijn |

Chairman of the Anti-Revolutionary Party 1879–1905 1907–1920 | Succeeded by Herman Bavinck | |

| Preceded by Herman Bavinck | Succeeded by Hendrikus Colijn | |

New office | Parliamentary leader of the Anti-Revolutionary Party in the House of Representatives 1894 1896–1901 1908–1912 | Succeeded by Jan van Alphen |

| Preceded by Jan van Alphen | ||

| Preceded by Jan Hendrik de Waal Malefijt | Succeeded by Gerrit Middelberg | |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Hendrik Goeman Borgesius | Minister of the Interior 1901–1905 | Succeeded by Pieter Rink |

| Preceded by Nicolaas Pierson | Prime Minister of the Netherlands 1901–1905 | Succeeded by Theo de Meester |

| Academic offices | ||

New office | Rector Magnificus of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam 1880–1881 1887–1888 | Succeeded by Frederik Rutgers |

| Preceded by Alexander de Savornin Lohman | ||