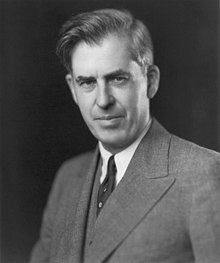

Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. Wallace | |

|---|---|

| |

| 33rd Vice President of the United States | |

In office January 20, 1941 – January 20, 1945 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | John Nance Garner |

| Succeeded by | Harry S. Truman |

| 10th United States Secretary of Commerce | |

In office March 2, 1945 – September 20, 1946 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Jesse H. Jones |

| Succeeded by | W. Averell Harriman |

| 11th United States Secretary of Agriculture | |

In office March 4, 1933 – September 4, 1940 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Arthur M. Hyde |

| Succeeded by | Claude R. Wickard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henry Agard Wallace (1888-10-07)October 7, 1888 Orient, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | November 18, 1965(1965-11-18) (aged 77) Danbury, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (Before 1936) Democratic (1936–1947) Progressive (1947–1950) |

| Spouse(s) | Ilo Browne (m. 1914) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Henry Cantwell Wallace (Father) |

| Education | Iowa State University (BS) |

| Signature | |

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, and farmer who served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture, the 33rd vice president of the United States, and the 10th U.S. secretary of commerce. He was also the presidential nominee of the left-wing Progressive Party in the 1948 election.

The oldest son of Henry Cantwell Wallace, who served as the U.S. secretary of agriculture from 1921 to 1924, Henry A. Wallace was born in Adair County, Iowa in 1888. After graduating from Iowa State University in 1910, Wallace worked as a writer and editor for his family's farm journal, Wallace's Farmer. He also founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company, a hybrid corn company that eventually became extremely successful. Wallace displayed an intellectual curiosity about a wide array of subjects, including statistics and economics, and he explored various religious and spiritual movements, including Theosophy. After the death of his father in 1924, Wallace increasingly drifted away from the Republican Party, and he supported Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 election.

Wallace served as secretary of agriculture under President Roosevelt from 1933 to 1940. He strongly supported Roosevelt's New Deal and presided over a major shift in federal agricultural policy, implementing measures designed to curtail agricultural surpluses and ameliorate rural poverty. Overcoming strong opposition from conservative party leaders, Wallace was nominated for vice president at the 1940 Democratic National Convention. The Democratic ticket of Roosevelt and Wallace triumphed in the 1940 presidential election, and Wallace continued to play an important role in the Roosevelt administration before and during World War II. At the 1944 Democratic National Convention, conservative party leaders defeated Wallace's bid for re-nomination, replacing him on the Democratic ticket with Harry S. Truman. The ticket of Roosevelt and Truman won the 1944 presidential election, and in early 1945 Roosevelt appointed Wallace as secretary of commerce.

Roosevelt died in April 1945 and was succeeded by Truman. Wallace continued to serve as secretary of commerce until September 1946, when Truman fired him for delivering a speech urging conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union. Wallace and his supporters established the Progressive Party and launched a third party campaign for president. The Progressive party platform called for conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union, desegregation of public schools, gender equality, free trade, a national health insurance program, and other left-wing policies. Accusations of Communist influences and Wallace's association with controversial Theosophist figure Nicholas Roerich undermined his campaign, and he received just 2.4 percent of the nationwide popular vote. Wallace broke with the Progressive Party in 1950 over the Korean War, and in 1952 he published Where I Was Wrong, in which he declared the Soviet Union to be "utterly evil." Wallace largely fell into political obscurity after the early 1950s, though he continued to make public appearances until the year before his death in 1965.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Journalist and farmer

2.1 Early political involvement

3 Secretary of Agriculture

4 Vice President

4.1 Election of 1940

4.2 Tenure

4.3 Election of 1944

5 Secretary of Commerce

6 1948 presidential election

7 Later career and death

8 Family

9 Religious explorations and Roerich controversy

10 Legacy

11 See also

12 Notes

13 References

14 Bibliography

14.1 Secondary sources

14.2 Works by Wallace

15 External links

Early life and education

Wallace was born on October 7, 1888 on a farm near Orient, Iowa, to Henry Cantwell Wallace and his wife, May.[1] Wallace had two younger brothers and three younger sisters.[2] His paternal grandfather, "Uncle Henry" Wallace, was an important landowner, newspaper editor, and Republican activist, and Social Gospel advocate in Adair County, Iowa. Uncle Henry's father, John Wallace, had migrated from Kilrea, Ireland in 1823.[3] May (née Broadhead) was born in New York City but was raised by an aunt in Muscatine, Iowa after the death of her parents.[4]

Wallace's family moved to Ames, Iowa in 1892 and to Des Moines, Iowa in 1896. In 1894, the Wallaces established an agricultural newspaper known as Wallace's Farmer.[5] The newspaper became extremely successful and made the Wallace family wealthy and politically influential.[6] Wallace took a strong interest in agriculture and plants from a young age, and he befriended African-American botanist George Washington Carver, with whom he frequently talked about plants and other subjects.[7] Wallace was particularly interested in corn, the key crop in Iowa. In 1904, he devised an experiment that disproved agronomist Perry Greeley Holden's assertion that the most aesthetically pleasing corn would produce the greatest yield.[8] Wallace graduated from West High School in 1906 and enrolled in Iowa State College later that year, majoring in animal husbandry. He joined the Hawkeye Club, a fraternal organization, and spent much of his free time continuing his study of corn.[9] He also organized a political club in support of Gifford Pinchot, a Progressive Republican who served as the head of the United States Forest Service.[10]

Journalist and farmer

Wallace's father, Henry Cantwell Wallace, served as secretary of agriculture from 1921 to his death in 1924.

Wallace became a full-time writer and editor for the family-owned paper, Wallace's Farmer, after he graduated college in 1910. He was deeply interested in using mathematics and economics in agriculture, and he learned calculus as part of an effort to understand hog prices.[11] He also wrote an influential article with pioneering statistician George W. Snedecor on computational methods for correlations and regressions[12] After the death of his grandfather in 1916, Wallace became the co-editor of Wallace's Farmer alongside his father.[13] In 1921, Wallace assumed leadership of the family paper after his father accepted appointment as secretary of agriculture under President Warren G. Harding.[14] His uncle lost ownership of the paper in 1932 due to the effects of the Great Depression, and Wallace stopped serving as editor of the paper in 1933.[15]

In 1914, Wallace and his wife purchased a farm near Johnston, Iowa; they initially attempted to combine corn production with dairy farming, but later turned their full attention to corn.[16] Influenced by Edward Murray East, Wallace focused on the production of hybrid corn, developing a hybrid corn known as Copper Cross. In 1923, Wallace reached the first ever contract for hybrid seed production when he agreed to grant the Iowa Seed Company the sole right to grow and sell Copper Cross corn.[17] In 1926, he co-founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company to develop and produce hybrid corn. Though it initially turned only a small profit, the Hi-Bred Corn Company eventually became a massive financial success.[18]

Early political involvement

During World War I, Wallace and his father helped the U.S. Food Administration to develop policies designed to increase the number of hogs.[19] After Herbert Hoover, the director of the U.S. Food Administration, abandoned the hog production policies favored by Wallace and his father, the Wallace's father became part of an effort to deny Hoover the presidential nomination at the 1920 Republican National Convention. Partly as a response to Hoover, Wallace published Agricultural Prices, in which he advocated for government policies designed to control agricultural prices.[20] He also warned farmers of an imminent price collapse following the end of the war; Wallace's prediction proved accurate, as the postwar period saw the beginning of a farm crisis that extended into the 1920s. Reflecting a broader decrease in agricultural prices, the price of corn fell from $1.68 per bushel in 1918 to 42 cents per bushel in 1921.[21] Wallace proposed various remedies to combat the farm crisis, which he believed stemmed primarily from overproduction by farmers. Among his proposed policies was the "ever-normal granary," a policy under which the government buys and stores agricultural surpluses during periods of low agricultural prices and sells those surpluses during periods of high agricultural prices.[22]

Both Wallaces backed the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill, which would have required the federal government to market and export agricultural surpluses in foreign markets. The bill was defeated in large part due to the opposition of President Calvin Coolidge, who became president after Harding's death in 1923.[23] Wallace's father died in October 1924, and in the November 1924 presidential election, Henry Wallace voted for progressive third party candidate Robert La Follette.[24] Partly due to Wallace's continued lobbying, Congress passed the McNary–Haugen bill in 1927 and 1928, but President Coolidge vetoed the bill both times.[25] Dissatisfied with both major party candidates in the 1928 presidential election, Wallace unsuccessfully attempted to convince Governor Frank Lowden of Illinois to seek the presidency. He ultimately supported Democratic nominee Al Smith, but the Republican nominee, Herbert Hoover, won a landslide victory.[26] The onset of the Great Depression during Hoover's presidency devastated Iowa farmers as farm income fell by two-thirds from 1929 to 1932.[27] In the 1932 presidential election, Wallace campaigned for Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was favorable towards the agricultural policies favored by Wallace and economist M. L. Wilson.[28]

Secretary of Agriculture

After Roosevelt defeated Hoover in the 1932 presidential election, he appointed Wallace as secretary of agriculture.[29] Despite his past affiliation with the Republican Party, Wallace strongly supported President Roosevelt and his New Deal domestic program, and he became a registered member of the Democratic Party in 1936.[30] Upon taking office, Wallace appointed Rexford Tugwell, a member of Roosevelt's "Brain Trust" of important advisers, as his deputy secretary. Though Roosevelt was initially focused primarily on addressing the banking crisis, Wallace and Tugwell convinced the president of the necessity of quickly passing major agricultural reforms.[31] Roosevelt, Wallace, and House Agriculture Committee Chairman John Marvin Jones rallied congressional support around the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which established the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA).[32] The aim of the AAA was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity by using a system of "domestic allotments" that set the total output of agricultural products. The AAA paid land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle.[33] Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose.[34] After the passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Department of Agriculture became the single largest department in the federal government.[35]

The Supreme Court struck down the Agricultural Adjustment Act in the 1936 case of United States v. Butler. Wallace strongly disagreed with the Court's holding that agriculture was a "purely local activity" and thus could not be regulated by the federal government, stating that "were agriculture truly a local matter in 1936, as the Supreme Court says it is, half of the people of the United States would quickly starve."[36] Nonetheless, he quickly proposed a new agriculture program designed to meet the Supreme Court's objections; under the new program, the federal government would reach rental agreements with farmers to plant green manure rather than crops like corn and wheat. Less than two months after the Supreme Court handed down United States v. Butler, Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936 into law.[37] In the 1936 presidential election, Wallace served as an important campaign surrogate for Roosevelt's successful re-election campaign.[38]

In 1935, Wallace fired general counsel Jerome Frank and some other Agriculture Department officials who sought to help Southern sharecroppers by issuing a reinterpretation of the Agricultural Adjustment Act.[39] Wallace became more committed to aiding sharecroppers and other groups of impoverished farmers as a result of a trip to the South in late 1936, after which he wrote, "I have never seen among the peasantry of Europe poverty so abject as that which exists in this favorable cotton year in the great cotton states." He helped lead passage of the Bankhead–Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937, which authorized the federal government to issue loans to tenant farmers so that they could purchase land and equipment. The law also established the Farm Security Administration,[a] which was charged with ameliorating rural poverty, within the Agriculture Department.[40] The failure of Roosevelt's Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, the onset of the Recession of 1937–38, and a wave of strikes led by John L. Lewis badly damaged the Roosevelt administration's ability to pass major legislation after 1936.[41] Nonetheless, Wallace helped lead passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, which implemented Wallace's ever-normal granary plan.[42] Between 1932 and 1940, the Agriculture Department grew from 40,000 employees and an annual budget of $280 million to 146,000 employees and an annual budget of $1.5 billion.[43]

A Republican wave in the 1938 elections effectively brought an end to the New Deal legislative program, and foreign policy increasingly became the focus of the Roosevelt administration.[44] Unlike many Midwestern progressives, Wallace supported internationalist policies, such as Secretary of State Cordell Hull's efforts to lower tariffs.[45] He joined Roosevelt in attacking the aggressive actions of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan, and in one speech derided Nazi eugenics as a "mumbo-jumbo of dangerous nonsense."[46] After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Wallace supported Roosevelt's program of military build-up and, anticipating future hostilities with Germany, pushed for initiatives like a synthetic rubber program and closer relations with Latin American countries.[47]

Vice President

Election of 1940

1940 electoral vote results

As Roosevelt refused to commit to either retiring or seeking re-election[b] during his second term, supporters of Wallace and other leading Democrats such as Vice President John Nance Garner and Postmaster General James Farley laid the groundwork for a presidential campaign in the 1940 election.[48] After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Wallace publicly endorsed a third term for Roosevelt.[49] Though Roosevelt never declared his presidential candidacy, the 1940 Democratic National Convention nominated him for president.[50] Shortly after being nominated, Roosevelt informed his supporters that he favored Wallace for the position of vice president. Wallace had a strong base of support among farmers, had been a loyal lieutenant in both domestic and foreign policy, and, unlike some other high-ranking New Dealers like Harry Hopkins, was in good health.[51] However, due to his liberal stances and former affiliation with the Republican Party, many conservative Democratic party leaders disliked Wallace.[52] Roosevelt convinced James F. Byrnes, Paul V. McNutt, and other contenders for the Democratic vice presidential nomination to support Wallace, but conservative Democrats rallied around the candidacy of Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead of Alabama. Ultimately, Wallace won the party's vice presidential nomination by a wide margin over Bankhead.[53]

Though many Democrats were disappointed by the nomination of Wallace, his selection was generally well-received by newspapers. Arthur Krock of The New York Times wrote that Wallace was "able, thoughtful, honorable–the best of the New Deal type."[54] Wallace left office as Secretary of Agriculture in September 1940, and was succeeded by Undersecretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard.[55] The Roosevelt campaign settled on a strategy of keeping Roosevelt largely out of the fray of the election, leaving most of the campaigning to Wallace and other surrogates. Wallace was dispatched to the Midwest, giving speeches in states like Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri. He made foreign affairs the main focus of his campaigning, telling one audience that "the replacement of Roosevelt ... would cause [Adolf] Hitler to rejoice."[56] Although both campaigns predicted a close election, Roosevelt won 449 of the 531 electoral votes and won the popular vote by a margin of nearly ten points.[57] As of 2019[update], Wallace is the most recent vice president who had never previously held an elected office.[citation needed] After the election, Wallace toured Mexico as a goodwill ambassador, delivering a well-received speech regarding Pan-Americanism and Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy. On his return from the trip, Wallace convinced the Rockefeller Foundation to establish an agricultural experiment center in Mexico, which would be the first of many such centers established by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation.[58][c]

Tenure

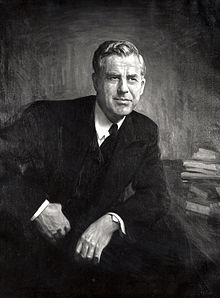

Vice President Henry Wallace

Wallace was sworn in as vice president on January 20, 1941. He quickly grew frustrated with his ceremonial role as the presiding officer of the United States Senate, the one duty assigned to the vice president by the Constitution.[60] Roosevelt named Wallace chairman of the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW)[d] and of the Supply Priorities and Allocation Board (SPAB) in 1941.[62] These appointments gave Wallace a key role in organizing Roosevelt's program of military mobilization. One journalist noted that Roosevelt made Wallace the first "vice president work really as the number two man in government–a conception of the vice presidency popularly held but never realized."[63] Reflecting Wallace's role in organizing mobilization efforts, many journalists began referring to him as the "Assistant President."[64][65] Wallace was also named to the Top Policy Group, which advised Roosevelt on the development of nuclear weapons, an initiative Wallace supported. He did not hold any official role in the subsequent Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear weapons, but he was informed on its progress.[66]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

Perhaps it will be America's opportunity to -- to support the Freedom[s] and Duties by which the common man must live. Everywhere, the common man must learn to build his own industries with his own hands in practical fashion. Everywhere, the common man must learn to increase his productivity so that he and his children can eventually pay to the world community all that they have received. No nation will have the God-given right to exploit other nations. Older nations will have the privilege to help younger nations get started on the path to industrialization, but there must be neither military nor economic imperialism."[67]

The United States entered World War II after the December 7, 1941 Attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan. In early 1942, Roosevelt established the War Production Board to coordinate war-time production, and named Donald Nelson, rather than Wallace, as the head of the board. Wallace became a member of the War Production Board and continued to serve as head of the BEW, which was charged with procuring and protecting the natural resources necessary for war production.[68] Wallace struggled to carve out authority for the BEW, clashing with both the State Department and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC).[69] On May 8, 1942, Wallace delivered what became his most famous speech, best known for containing the phrase "the Century of the Common Man". He cast World War II as a war between a "free world" and a "slave world," and held that "peace must mean a better standard of living for the common man, not merely in the United States and England, but also in India, Russia, China, and Latin America–not merely in the United Nations, but also in Germany and Italy and Japan." Though some conservatives disliked the speech, it was translated into twenty languages, and millions of copies were distributed around the world.[70]

In early 1943, Wallace was dispatched on a goodwill tour of Latin America; he made twenty-four stops across Central America and South America. Partly due to his ability to deliver speeches in Spanish, Wallace received a warm reception; one State Department official noted that "never in Chilean history has any foreigner ever been received with such extravagance and evidently sincere enthusiasm." During his trip, several Latin American countries declared war against Germany.[71] After a long, public battle between Wallace and RFC head Jesse H. Jones, in July 1943 Roosevelt abolished the BEW and replaced it with the newly-created the Office of Economic Warfare, led by Leo Crowley.[72] The abolition of the BEW was widely viewed as a major blow to Wallace's standing within the administration, but Wallace remained a loyal supporter of the president. He continued to deliver speeches, stating after the Detroit race riot of 1943 that "we cannot fight to crush Nazi brutality abroad and condone race riots at home."[73] Though Roosevelt's domestic agenda was largely blocked by Congress, Wallace continued to call for the passage of progressive programs; one newspaper wrote that "the New Deal today is Henry Wallace ... the New Deal banner in his hands is not yet furled."[74]

In mid-1944, Wallace embarked on a tour of the Soviet Union and China.[75] The Soviet Union presented a fully sanitized version of labor camps in Magadan and Kolyma to their American guests, claiming that all the work was done by volunteers.[76] Wallace was impressed by the camp at Magadan, describing it as a "combination Tennessee Valley Authority and Hudson's Bay Company."[77][e] He received a warm reception in the Soviet Union, but was largely unsuccessful in his efforts to negotiate with Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek.[79]

Election of 1944

After the abolition of the BEW in mid-1943, speculation began as to whether Roosevelt would drop Wallace from the ticket in the 1944 election.[80] Nonetheless, Gallup polling published in March 1944 showed that Wallace was by far the most popular choice for vice president among Democrats, and many journalists predicted that he would win re-nomination.[81] As Roosevelt was in declining health, party leaders expected that the party's vice presidential nominee would eventually succeed Roosevelt,[82] and Wallace's many enemies within the Democratic Party organized to ensure his defeat.[83] Much of the opposition to Wallace stemmed from his open denunciation of racial segregation in the South,[82] but others were concerned by Wallace's unorthodox religious views and pro-Soviet statements.[84] Shortly before the 1944 Democratic National Convention, party leaders such as Robert E. Hannegan and Edwin W. Pauley convinced Roosevelt to sign a document expressing support for either Associate Justice William O. Douglas or Senator Harry S. Truman for the vice presidential nomination. Nonetheless, Wallace convinced Roosevelt to send a public letter to the convention chairman in which he stated, "I personally would vote for [Wallace's] renomination if I were a delegate to the convention."[85]

With Roosevelt not fully committed to keeping or dropping Wallace, the vice presidential balloting turned into a battle between those who favored Wallace and those who favored Truman.[86] Wallace did not organize an effective organization in support of his candidacy, though allies like Calvin Benham Baldwin, Claude Pepper, and Joseph F. Guffey pressed for him. Truman, meanwhile, was reluctant to put forward his own candidacy, but Hannegan[f] and Roosevelt convinced him to run.[88] At the convention, Wallace galvanized supporters with a well-received speech in which he lauded Roosevelt and argued that "the future belongs to those who go down the line unswervingly for the liberal principles of both political democracy and economic democracy regardless of race, color or religion."[89] After Roosevelt delivered his acceptance speech, the crowd began chanting for the nomination of Wallace, but Samuel D. Jackson adjourned the convention for the day before Wallace supporters could call for the beginning of vice presidential balloting.[90] Party leaders worked furiously to line up support for Truman overnight, but Wallace received 429 1/2 votes (589 were needed for nomination) on the first ballot for vice president; Truman finished with 319 1/2 votes, and the remaining votes went to various favorite son candidates. On the second ballot, many delegates who had voted for favorite sons shifted into Truman's camp, giving him the nomination.[91]

Secretary of Commerce

Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace

Wallace believed that Democratic party leaders had unfairly stolen the vice presidential nomination from him, but he supported Roosevelt's ultimately successful campaign in the 1944 presidential election. Roosevelt, hoping to mend ties with his popular vice president, offered Wallace any position in the Cabinet other than that of secretary of state, and Wallace asked to replace his old rival Jones as secretary of commerce.[92] In that position, Wallace expected to play a key role in the postwar transition of the economy.[93] In January 1945, with the end of Wallace's term as vice president, Roosevelt nominated Wallace for the position of secretary of commerce.[94] Wallace's nomination prompted an intense debate as many senators objected to his support for liberal policies designed to boost wages and employment.[95] Conservatives failed to block the nomination, but Senator Walter F. George led passage of a measure removing the RFC from the Commerce Department.[96] After Roosevelt signed George's bill, Wallace was confirmed by a vote of 56 to 32 on March 1, 1945.[97]

Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and was succeeded by Truman.[98] Truman quickly replaced most other senior Roosevelt appointees,[g] but he retained Wallace, who remained widely popular with liberal Democrats.[100] The discontent of liberal leaders strengthened Wallace's position in the Cabinet; Truman privately stated that the two most important members of his "political team" were Wallace and Eleanor Roosevelt.[101] As secretary of commerce, Wallace advocated for a "middle course" between the planned economy of the Soviet Union and the laissez-faire economics that had dominated the United States prior to the Great Depression. With his congressional allies, he led passage of the Employment Act of 1946. Although conservatives blocked the inclusion of a measure providing for full employment, the act established the Council of Economic Advisers and the Joint Economic Committee to study economic matters.[102] Wallace's proposal to establish international control over nuclear weapons was not adopted, but he did help pass the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which established the United States Atomic Energy Commission to oversee domestic development of nuclear power.[103]

World War II came to an end in September 1945 with the Surrender of Japan, and relations with the Soviet Union became a central matter of foreign policy. Various issues, including the fate of post-war governments in Europe and Asia and the administration of the United Nations, had already begun to strain the wartime alliance between the Soviet Union and the United States.[104] Critics of the Soviet Union objected to the oppressive satellite states that the Soviet Union established in Eastern Europe and Soviet involvement in the Greek Civil War and the Chinese Civil War. In February 1946, George F. Kennan laid out the doctrine of containment, which called for the United States to resist the spread of Communism.[105] Wallace feared that confrontational policies towards the Soviet Union would eventually lead to war, and he urged Truman to "allay any reasonable Russian grounds for fear, suspicion, and distrust."[106] Historian Tony Judt, notes that Wallace's "distaste for American involvement with Britain and Europe was widely shared across the political spectrum."[107]

Though Wallace was dissatisfied with Truman's increasingly confrontational policies towards the Soviet Union, he remained an integral part of Truman's Cabinet during the first half of 1946.[108] Wallace broke with the president in September 1946 after he delivered a speech in which he stated that "we should recognize that we have no more business in the political affairs of Eastern Europe than Russia has in the political affairs of Latin America, Western Europe and the United States." Though Wallace's speech was booed by the pro-Soviet Union crowd he delivered it to, it was even more strongly criticized by Truman administration officials and leading Republicans like Robert A. Taft and Arthur Vandenberg.[109] Truman stated that Wallace's speech did not represent administration policy but merely Wallace's personal views, and on September 20 he demanded and received Wallace's resignation.[110]

1948 presidential election

Shortly after leaving office, Wallace became the editor of The New Republic, a progressive magazine.[111] He also helped establish the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA), a progressive political organization that accepted members regardless of race, creed, or political affiliation. Though Wallace was not a member of the PCA, he was widely regarded as the organization's leader and was criticized for the PCA's acceptance of Communist members. In response to the creation of the PCA, anti-Communist liberals established a rival group, Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), which explicitly rejected any association with Communism.[112] Wallace strongly criticized the president in early 1947 after Truman promulgated the Truman Doctrine and issued Executive Order 9835, which began a purge of government workers affiliated with political groups deemed to be subversive.[113] He initially favored the Marshall Plan, but later opposed it because he believed the program should have been administered through the United Nations.[114] Wallace and the PCA began receiving close scrutiny from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), both of which sought to uncover evidence of Communist influence.[115]

Many in the PCA favored the establishment of a third party, but other long-time Wallace allies warned him against leaving the Democratic Party.[116] On December 29, 1947, Wallace launched a third party campaign, declaring, "we have assembled a Gideon's Army, small in number, powerful in conviction ... We face the future unfettered, unfettered by any principal but the general welfare."[117] He won backing from many intellectuals, union members, and military veterans; among his prominent supporters were Rexford Tugwell, Congressmen Vito Marcantonio and Leo Isacson, musicians Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger, and future presidential nominee George McGovern.[118] Calvin Baldwin became Wallace's campaign manager and took charge of fundraising and ensuring that Wallace appeared on as many state ballots as possible.[119] Wallace's first choice for running mate, Claude Pepper, refused to leave the Democratic Party, but Democratic Senator Glen H. Taylor of Idaho agreed to serve as Wallace's running mate.[120] Wallace accepted the endorsement of the Communist Party USA, stating, "I'm not following their line. If they want to follow my line, I say God bless em."[121] Truman responded to Wallace's left-wing challenge by pressing for liberal domestic policies, while pro-ADA liberals like Hubert Humphrey, Robert Wagner, and James Roosevelt linked Wallace to the Soviet Union and the Communist Party.[122] Many Americans came to see Wallace as a fellow traveller to Communists, a view that was reinforced by Wallace's refusal to condemn the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état.[123] In early 1948, the CIO and the AFL both rejected Wallace, with the AFL denouncing him as a "front, spokesman, and apologist for the Communist Party."[124] With Wallace's foreign policy views overshadowing his domestic policy views, many liberals who had previously favored his candidacy returned to the Democratic fold.[125]

Wallace embarked on a nationwide speaking tour in support of his candidacy, encountering resistance in both the North and South.[126] He openly defied the Jim Crow regime in the South, refusing to speak before segregated audiences.[127]Time magazine, which opposed the Wallace candidacy, described Wallace as "ostentatiously" riding through the towns and cities of the segregated South "with his Negro secretary beside him".[128] A barrage of eggs and tomatoes were hurled at Wallace and struck him and his campaign members during the tour. State authorities in Virginia sidestepped enforcing their own segregation laws by declaring Wallace's campaign gatherings as private parties.[129] The Pittsburgh Press began publishing the names of known Wallace supporters, and many pro-Wallace academics lost their positions.[130] With strong support from Anita McCormick Blaine, Wallace exceeded fundraising goals, and he ultimately appeared on the ballot of every state except for Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Illinois.[131] However, Gallup polling showed support for Wallace falling from seven percent in December 1947 to five percent in June 1948, and some in the press began to speculate that Wallace would drop out of the race.[132] Nationwide, just three newspapers endorsed Wallace's candidacy; one of those papers was the National Guardian, which was established in 1948 by Norman Mailer and other Wallace supporters.[133]

Wallace's supporters held a national convention in Philadelphia in July, formally establishing the Progressive Party.[134][h] The party platform addressed a wide array of issues, and included support for the desegregation of public schools, gender equality, a national health insurance program, free trade, and public ownership of large banks, railroads, and power utilities.[136][i] Another part of the platform stated, "responsibility for ending the tragic prospect of war is a joint responsibility of the Soviet Union and the United States."[138] During the convention, Wallace faced questioning regarding letters he had written to guru Nicholas Roerich; his refusal to comment on the letters was widely criticized.[139] Wallace was further damaged days after the convention when Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley testified before the House Unamerican Activities Committee that several government officials associated with Wallace (including Alger Hiss and John Abt) were Communist infiltrators.[140] Meanwhile, many Southern Democrats, outraged by the Democratic Party's pro-civil rights plank, bolted the party and nominated Strom Thurmond for president. With the Democrats badly divided, Republicans were confident that Republican nominee Thomas Dewey would win the election.[141] Wallace himself predicted that Truman would be "the worst defeated candidate in history."[142]

Though polls consistently showed him losing the race, Truman ran an effective campaign against Dewey and the conservative 80th United States Congress. He ultimately defeated Dewey in both the popular and electoral vote.[143] Wallace won just 2.38 percent of the nationwide popular vote, and failed to carry any state. His best performance was in New York, where he won eight percent of the vote. Just one of the party's congressional candidates, incumbent Congressman Vito Marcantonio, won election.[144] Though Wallace and Thurmond probably took many voters from Truman, their presence in the race may have boosted the president's overall appeal by casting him as the candidate of the center-left.[145] In response to the election results, Wallace stated, "Unless this bi-partisan foreign policy of high prices and war is promptly reversed, I predict that the Progressive Party will rapidly grow into the dominant party. ... To save the peace of the world the Progressive Party is more needed than ever before."[146]

Later career and death

Wallace initially remained active in politics following the 1948 campaign, and he delivered the keynote address at the 1950 Progressive National Convention. In early 1949, Wallace testified before Congress in the hope of preventing the ratification of the North Atlantic Treaty, which established the NATO alliance between the United States, Canada, and several European countries.[147] He became increasingly critical of the Soviet Union after 1948, and he resigned from the Progressive Party in August 1950 due to his support for the UN intervention in the Korean War.[148] After leaving the Progressive Party, Wallace endured what biographers John Culver and John Hyde describe as a "long, slow decline into obscurity marked by a certain acceptance of his outcast status."[149] In the early 1950s, he spent much of his time rebutting attacks by prominent public figures like General Leslie Groves, who claimed to have stopped providing Wallace with information regarding the Manhattan Project because he considered Wallace to be a security risk. In 1951, Wallace appeared before Congress to deny accusations that in 1944 he had encouraged a coalition between Chiang-Kai Shek and the Chinese Communists.[150] In 1952, he published an article, Where I Was Wrong, in which he repudiated his earlier foreign policy positions and declared the Soviet Union to be "utterly evil."[64]

Wallace continued to co-own and take an interest in the company he had established, Pioneer Hi-Bred (formerly known as the Hi-Bred Corn Company), and he established an experimental farm at his New York estate. He focused much of his efforts on the study of chickens, and Pioneer Hi-Bred's chickens at one point constituted three-quarters of all commercially sold eggs worldwide. He also wrote or co-wrote several works on agricultural, including a book on the history of corn.[151]

Wallace did not endorse a candidate in the 1952 presidential election, but in the 1956 presidential election he endorsed incumbent Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower over Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. Wallace, who maintained a correspondence with Eisenhower, described Eisenhower as "utterly sincere" in his efforts for peace.[152] Wallace also began a correspondence with Vice President Richard Nixon, but he declined to endorse either Nixon or Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election. Though Wallace criticized Kennedy's farm policy during the 1960 campaign, Kennedy invited Wallace to his 1961 inauguration, the first presidential inauguration Wallace had attended since 1945. Wallace later wrote Kennedy, "at no time in our history have so many tens of millions of people been so completely enthusiastic about an inaugural address as about yours." In 1962, he delivered a speech commemorating the centennial anniversary of the establishment of the Department of Agriculture.[153] He also began a correspondence with President Lyndon B. Johnson regarding methods to alleviate rural poverty, though privately he criticized Johnson's escalation of American involvement in the Vietnam War.[154] Due to declining health, he made his last public appearance in 1964; in one of his last speeches, he stated, "We lost Cuba in 1959 not only because of Castro but also because we failed to understand the needs of the farmer in the back country of Cuba from 1920 onward. ... The common man is on the march, but it is up to the uncommon men of education and insight to lead that march constructively."[155]

Wallace was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1964. He consulted numerous specialists and tried various methods of treating the disease, stating, "I look on myself as an ALS guinea-pig, willing to try almost anything."[156] He died in Danbury, Connecticut, on November 18, 1965.[157] His remains were cremated and the ashes interred in Glendale Cemetery in Des Moines, Iowa.[158] Due to his successful business career and wise investments, he left an estate valued at tens of millions of dollars.[159]

Family

In 1913, Wallace met Ilo Browne, the daughter of a successful businessman from Indianola, Iowa.[160] Wallace and Browne married on May 20, 1914, and had three children.[161] Henry Browne was born on 1915, Robert Browne was born in 1918, and Jean Browne was born in 1920.[162] Wallace and his family lived in Des Moines until Wallace accepted appointment as secretary of agriculture, at which point they began living in an apartment at Wardman Park in Washington, D.C.[163] In 1945, Wallace and his wife purchased a 115-acre farm near South Salem, New York known as Farvue.[164] Ilo was supportive of her husband's career and enjoyed serving as Second Lady of the United States from 1941 to 1945, though she was uncomfortable with many of Wallace's Progressive supporters during his 1948 presidential campaign.[165] Wallace and Ilo remained married until his death in 1965; she lived until 1981. In 1999, Wallace's three children sold their shares in Pioneer Hi-Bred to DuPont for well over $1 billion.[166] Wallace's grandson, Scott Wallace, won the Democratic nomination for Pennsylvania's 1st congressional district in the 2018 elections, but he was defeated by Republican incumbent Brian Fitzpatrick.[167]

Religious explorations and Roerich controversy

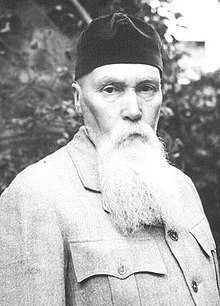

Wallace associated with controversial Russian Theosophist Nicholas Roerich

Wallace was raised in the Calvinist branch of Protestant Christianity, but showed an interest in other religious teachings during his life.[65] He was deeply interested in religion from a young age, reading works by authors like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ralph Waldo Trine, and William James, whose The Varieties of Religious Experience had a particularly strong impact on Wallace.[168] After his grandfather's death in 1916, he left the Presbyterian Church and became increasingly interested in mysticism. He later said, "I know I am often called a mystic, and in the years following my leaving the United Presbyterian Church I was probably a practical mystic ... I'd say I was a mystic in the sense that George Washington Carver was – who believed God was in everything and therefore, if you went to God, you could find the answers." Wallace began regularly attending meetings of the pantheistic Theosophical Society, and, in 1925, he helped organize the Des Moines parish of the Liberal Catholic Church.[169] Wallace left the Liberal Catholic Church in 1930 and joined the Episcopal Church, but he continued to be interested in various mystic groups and individuals.[170]

Among those who Wallace corresponded with were author George William Russell,[171] astrologer L. Edward Johndro, and Edward Roos, who took on the persona of a Native American medicine man.[172] In the early 1930s, Wallace began corresponding with Nicholas Roerich, a prominent Russian émigré, artist, peace activist, and Theosophist.[173] With Wallace's support, Roerich was appointed to lead a federal expedition to the Gobi Desert to collect drought-resistant grasses.[174] Roerich's expedition ended in a public fiasco, and Roerich fled to India after the Internal Revenue Service launched a tax investigation.[175]

The letters that Wallace wrote to Roerich from 1933 to 1934 were eventually acquired by Republican newspaper publisher Paul Block.[176] The Republicans threatened to reveal to the public what they characterized as Wallace's bizarre religious beliefs prior to the November 1940 elections but were deterred when the Democrats countered by threatening to release information about Republican candidate Wendell Willkie's rumored extramarital affair with the writer Irita Van Doren.[177] The contents of the letters did become public seven years later, in the winter of 1947, when right-wing columnist Westbrook Pegler published what were purported to be extracts from them as evidence that Wallace was a "messianic fumbler", and "off-center mentally". During the 1948 campaign Pegler and other hostile reporters, including H. L. Mencken, aggressively confronted Wallace on the subject at a public meeting in Philadelphia in July. Wallace declined to comment, accusing the reporters of being Pegler's stooges.[178] Many press outlets were critical of Wallace's association with Roerich; one newspaper mockingly wrote that if Wallace became president "we shall get in tune with the Infinite, vibrate in the correct plane, outstare the Evil Eye, reform the witches, overcome all malicious spells and ascend the high road to health and happiness."[179]

Legacy

During his time in the Roosevelt administration, Wallace became a controversial figure, attracting a mix of praise and criticism for various actions.[180][65] He remains a controversial figure today.[181][182][183] Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. pronounced Wallace to be both "an incorrigibly naive politician" and "the best secretary of agriculture the country has ever had."[184] Journalist Peter Beinart writes that Wallace's "naive faith in U.S.-Soviet cooperation" damaged his legacy.[185] Will Moreland of the Brookings Institution writes that Wallace was "too blinded by his self-messianic vision to realize he ... had become a Kremlin pawn."[186] Historian Andrew Seal lauds Wallace for his focus on combating both economic and racial inequality.[182] Wallace's vision of the "Century of the Common Man," which denied American exceptionalism in foreign policy, continues to influence the foreign policy of individuals like Bernie Sanders.[185] In 2013, historian Thomas W. Devine wrote that "newly available Soviet sources do confirm Wallace's position that Moscow's behavior was not as relentlessly aggressive as many believed at the time." Yet Devine also writes that "enough new information has come to light to cast serious doubt both on Wallace's benign attitude toward Stalin's intentions and on his dark, conspiratorial view of the Truman administration."[187]

Alex Ross of The New Yorker writes, "with the exception of Al Gore, Wallace remains the most famous almost-president in American history."[64] Journalist Jeff Greenfield writes that the 1944 Democratic National Convention was one of the most important political events of the twentieth century, since the leading contenders for the nomination might have governed in vastly different ways.[82] In The Untold History of the United States, Oliver Stone argues that, had Wallace become president in 1945, "there might have been no atomic bombings, no nuclear arms race, and no Cold War.”[188][189] By contrast, Ron Capshaw of the conservative National Review argues that a President Wallace would have practiced a policy of appeasement that would have allowed the spread of Communism into countries like Iran, Greece, and Italy.[190]

The Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland, the largest agricultural research complex in the world, is named for him. Wallace founded the Wallace Genetic Foundation to support agricultural research. His son, Robert, founded the Wallace Global Fund to support sustainable development.[181] A speech Wallace delivered in 1942 inspired Aaron Copland to compose Fanfare for the Common Man.[64]

See also

- History of left-wing politics in the United States

Honeydew (melon), apparently first introduced to China by H. A. Wallace and still known there as the "Wallace melon"[191][192]

Bailan melon, one of the most famous Chinese melon cultivars, bred from the "Wallace melon"

Notes

^ The Farm Security Administration succeeded the Resettlement Administration, which had been an independent agency.

^ The Twenty-second Amendment, ratified in 1951, would later prevent presidents from running for a third term.

^ Norman Borlaug would later credit Wallace as a key initiator of the Green Revolution.[59]

^ The BEW was originally known as the Economic Defense Board[61]

^ Wallace later regretted his praise of the camp at Magadan, writing in 1952 that he "had not the slightest idea when I visited Magadan that this ... was also the center for administering the labor of both criminals and those suspected of political disloyalty."[78]

^ Hannegan later stated that he would like his tombstone to read, "here lies the man who stopped Henry Wallace from becoming President of the United States."[87]

^ After the resignation of Harold L. Ickes in February 1946, Wallace was the lone remaining holdover from Roosvelt's Cabinet.[99]

^ The party was influenced by, and took the same name as, defunct parties that had backed Theodore Roosevelt (in 1912) and Robert La Follette (in 1924).[135]

^ Wallace did not dictate the party platform, and he personally opposed public ownership of banks, railroads, and utilities.[137]

References

^ Southwick (1998), p. 620

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 23–24

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 3–10

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 9–10

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 11–17

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 21–22

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 13–14

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 26–29

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 29–34

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 37

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 37–39

^ Wallace, Henry Agard; Snedecor, George Waddel (1925). "Correlation and Machine Calculation". Iowa State College Bulletin. 35.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 42–44

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 53–55

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 92–93, 110

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 40–41

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 67–70

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 82–83

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 46–48

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 50–52

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 52–53

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 56–59

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 62–63

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 64–65, 71

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 84–85

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 86–87

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 99–100

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 102–104

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 105–107

^ Kennedy (1999), p. 457

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 113–114

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 115–119

^ Ronald L. Heinemann, Depression and New Deal in Virginia. (1983) p. 107

^ Anthony Badger, The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933–1940 (2002) p. 89. 153-57

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 120–122

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 157–160

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 160–161

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 163–167

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 154–157

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 169–171

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 174–176

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 178–179

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 237

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 185–186, 192

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 191–192

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 193–194

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 206–207

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 179–180

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 200–201

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 213–217

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 209, 217–218

^ Kennedy (1999), pp. 457–458

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 218–223

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 223–225

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 225–226

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 231–236

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 244–245

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 246–251

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 250–251

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 251–254

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 269

^ Arthur (2012), pp. 152-153, 155, 162-164, 196

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 256–258

^ abcd Ross, Alex (October 14, 2013). "Uncommon Man". The New Yorker.

^ abc Hatfield, Mark O. "Vice Presidents of the United States Henry Agard Wallace (1941-1945)" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 266–268

^ "Henry A. Wallace: The Century of the Common Man". American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 269–271

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 271–273

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 275–279

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 296–300

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 308–309

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 310–311

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 322–324

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 330–331

^ Tim Tzouliadis. The Forsaken. The Penguin Press (2008). pp. 217–226. ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 339

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 339

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 333–335

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 317–318

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 324–325

^ abc Greenfield, Jeff (July 10, 2016). "The Year the Veepstakes Really Mattered". Politico. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 340–342

^ Helling, Dave (July 18, 2016). "1944 Democratic Convention: Choosing not just a VP candidate but a president-in-waiting". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 345–352

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 352–353

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 365

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 357–359

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 359–361

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 362–364

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 364–366

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 367–373

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 379–380

^ Donovan (1977), p. 113

^ Malsberger (2000), p. 131.

^ Malsberger (2000), pp. 131–132.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 384

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 385–387

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 411

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 388–390

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 408–409

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 395–396

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 404–406, 427

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 396–398

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 411–412

^ Patterson (1996), p. 124

^ Tony Judt (2005). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. The Penguin Press. p. 110.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 409–417

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 420–422

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 422–426

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 431–432

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 433–435

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 436–438

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 451–453, 457

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 446–450

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 452–454

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 456–457

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 481, 484–485, 488

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 460–461

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 462–463

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 452, 464–466

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 465–466

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 464, 473–474

^ Karabell (2007), p. 68

^ Patterson (1996), p. 157

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 467–469

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 493–494

^ "National Affairs – Eggs in the Dust". Time. September 13, 1948. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

^ "Am I in America?". Time. September 6, 1948. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 468–469

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 498–499

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 478

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 497

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 480, 486

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 486

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 480–481

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 481

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 487

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 482–484

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 491–493

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 478–480

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 500

^ Patterson (1996), pp. 159–162

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 500–502

^ Patterson (1996), p. 162

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 500–502

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 503–506

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 505, 507–509

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 510–511

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 512–517

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 517–510

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 521–522

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 522–524

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 529

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 527

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 527–529

^ Southwick (1998), p. 620

^ "Wallace, Henry Agard, (1888 – 1965)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

^ "The ex-wife of former Vice President Henry A. Wallace's ..." UPI. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 39–40

^ Southwick (1998), p. 620

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 49

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 187–188, 256

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 402–403

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 187–188, 496–497

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 49

^ Otterbein, Holly; McDaniel, Justine; McCrystal, Laura (November 7, 2018). "Republican Brian Fitzpatrick wins Pa.'s First Congressional District, defies Dem tide". Philly.com.

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 31–32

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 77–79

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 96

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), p. 39

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 96–97

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 130–132

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 135–137

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 143–144

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 231–233

^ "The religion of Henry A. Wallace, U.S. Vice-President".

^ Westbrook Pegler (July 27, 1948). "In Which Our Hero Beards 'Guru' Wallace In His Own Den". As Pegler Sees It (column). The Evening Independent (St. Peteresburg, Fla.).

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 483–484

^ Culver & Hyde (2000), pp. 312

^ ab Gross, Daniel (January 8, 2004). "Seed Money". Slate. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ ab Seal, Andrew (June 8, 2018). "What a former vice president can teach Democrats about racial and economic inequality". Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

^ Hornaday, Ann (November 11, 2012). "'Oliver Stone's Untold History of the United States': Facts through a new lens". Washington Post. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. (March 12, 2000). "Who Was Henry A. Wallace ?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ ab Beinart, Peter (October 15, 2018). "Bernie Sanders Offers a Foreign Policy for the Common Man". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Moreland, Will (October 26, 2016). "The last Russian leader to mess with a US election? Josef Stalin". Vox. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Devine (2013), p. xiv

^ Wiener, John (November 14, 2012). "Oliver Stone's 'Untold History'". The Nation. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Goldman, Andrew (November 22, 2012). "Oliver Stone Rewrites History — Again". New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

^ Capshaw, Ron (April 4, 2015). "Henry Wallace: Unsung Hero of the Left". National Review. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

^ Dirlik, Arif; Wilson, Rob (1995). Asia/Pacific as space of cultural production. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1643-9.

^ A Guide to the Barbarian Vegetables of China Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Lucky Peach, June 30, 2015

Bibliography

Secondary sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Busch, Andrew (2012). Truman's Triumphs: The 1948 Election and the Making of Postwar America. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700618675.

Conant, Jennet (2008). The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0743294584.

Culver, John C.; Hyde, John (2000). American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04645-1.

Devine, Thomas W. (2013). Henry Wallace's 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469602035.

Donovan, Robert J. (1977). Conflict and Crisis: the Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945–1948. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0393056365.

Dunn, Susan (2013). 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler-the Election amid the Storm. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300190861.

Ferrell, Robert H. (1994). Choosing Truman: The Democratic Convention of 1944. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0826209481.

Herman, Arthur (2012). Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

Jordan, David M. (2011). FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253356833.

Karabell, Zachary (2007). The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 9780307428868.

Kennedy, David M. (1999). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195038347.

MacDonald, Dwight (1948). Henry Wallace: the Man and the Myth. Vanguard Press. OCLC 597926.

Malsberger, John William (2000). From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938–1952. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-1575910260.

Markowitz, Norman D. (1973). The Rise and Fall of the People's Century: Henry A. Wallace and American Liberalism, 1941–1948. Free Press. ISBN 978-0029200902.

Maze, John; White, Graham (1995). Henry A. Wallace: His Search for a New World Order. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807821893.

McCoy, Donald R. (1984). The Presidency of Harry S. Truman. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0252-0.

Patterson, James T. (1996). Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743957.

Pietrusza, David (2011). 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America. Union Square Press. ISBN 978-1402767487.

Schapsmeier, Edward L.; Schapsmeier, Frederick H. (1968). Henry A. Wallace in Iowa: the Agrarian Years, 1910–1940. Iowa University Press. ISBN 9780813817415.

Schapsmeier, Edward L.; Schapsmeier, Frederick H. (1970). Prophet in Politics: Henry A. Wallace and the War Years, 1940–1965. Iowa University Press. ISBN 9780813812953.

Schmidt, Karl M. (1960). Henry A. Wallace, Quixotic Crusade 1948. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815600208.

Southwick, Leslie (1998). Presidential Also-Rans and Running Mates, 1788 through 1996 (Second ed.). McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0310-1.

Walker, J. Samuel (1976). Henry A. Wallace and American Foreign Policy. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780837187747.

Witcover, Jules (2014). The American Vice Presidency: From Irrelevance to Power. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588344724.

Works by Wallace

Agricultural Prices (1920)

New Frontiers (1934)

America Must Choose (1934)

Statesmanship and Religion (1934)

Technology, Corporations, and the General Welfare (1937)

The Century of the Common Man (1943)

Democracy Reborn (1944)

Sixty Million Jobs (1945)

Soviet Asia Mission (1946)

Toward World Peace (1948)

Where I Was Wrong (1952)

The Price of Vision – The Diary of Henry A. Wallace 1942–1946 (1973), edited by John Morton Blum

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Wallace. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry A. Wallace |

United States Congress. "Henry A. Wallace (id: W000077)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- The Wallace Global Fund

- Selected Works of Henry A. Wallace

- The text of Wallace's 1942 speech "The Century of the Common Man"

- As delivered transcript and complete audio of Wallace's 1942 "The Century of the Common Man" Address

- Papers of Henry Wallace Digital Collection

- Searchable index of Wallace papers at the Library of Congress, Franklin D Roosevelt Library, and the University of Iowa

- "Henry A. Wallace – Agricultural Pioneer, Visionary and Leader", Iowa Pathways, education site of Iowa Public Television

- "The Life of Henry A. Wallace: 1888–1965", on website of The Wallace Center for Agricultural and Environmental Policy at Winrock International

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Henry A. Wallace (December 28, 1951)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Henry Agard Wallace (October 17, 1952)" is available at the Internet Archive

"Is There Any 'Wallace' Left in the Democratic Party?", The Real News (TRNN). Scott Wallace, grandson of Henry A. Wallace, interviewed by Paul Jay (video).- FBI file on Henry Wallace

The Country Life Center location of The Wallace Centers of Iowa: birthplace farm of Henry A. Wallace. Museum and gardens.

Newspaper clippings about Henry A. Wallace in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arthur M. Hyde | United States Secretary of Agriculture 1933–1940 | Succeeded by Claude R. Wickard |

| Preceded by John Nance Garner | Vice President of the United States 1941–1945 | Succeeded by Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by Jesse H. Jones | United States Secretary of Commerce 1945–1946 | Succeeded by W. Averell Harriman |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by John Nance Garner | Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States 1940 | Succeeded by Harry S. Truman |

New political party | Progressive nominee for President of the United States 1948 | Succeeded by Vincent Hallinan |

| Preceded by Franklin D. Roosevelt | American Labor nominee for President of the United States Endorsed 1948 | |