Deccan sultanates

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Deccan Sultanates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1527 CE–1686 CE | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ahmednagar Berar Bidar Bijapur Golkonda | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian(official) Marathi Kannada Dakhini Telugu | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Shah | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Medieval | ||||||||||

• Established | 1527 CE | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1686 CE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Palaeolithic .mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} (2,500,000–250,000 BC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early modern period (1526–1858)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colonial states (1510–1961)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Periods of Sri Lanka

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

National histories

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Regional histories

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Specialised histories

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Deccan Sultanates were five Muslim dynasties that ruled several late medieval Indian kingdoms, namely Bijapur, Golkonda, Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Berar in south-western India. The Deccan sultanates were located on the Deccan Plateau, between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. These kingdoms became independent during the break-up of the Bahmani Sultanate. They were noted for the destruction of temples and general economic misery.[1][2] In 1490, Ahmadnagar declared independence, followed by Bijapur and Berar in the same year. Golkonda became independent in 1518 and Bidar in 1528.[3]

The five sultanates were of diverse origin; the Ahmadnagar Sultanate and Berar Sultanate were of Hindu lineage (Ahmadnagar being Brahmin-Hindu and Berar being Kanarese-Hindu),[4] the Bidar Sultanate being founded by a former Turkic slave,[5] the Bijapur Sultanate was founded by a Georgian-Oghuz Turkic slave,[6] and the Golconda Sultanate was of Turkmen origin.[7]

Although generally rivals, they did ally against the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565, permanently weakening Vijayanagar in the Battle of Talikota. Notably, the alliance destroyed the entire city of Vijayanagar with important temples such as the Vitthala Temple being razed to the ground. In 1574, after a coup in Berar, Ahmadnagar invaded and conquered it. In 1619, Bidar was annexed by Bijapur. The sultanates were later conquered by the Mughal Empire; Berar was stripped from Ahmadnagar in 1596, Ahmadnagar was completely taken between 1616 and 1636, and Golkonda and Bijapur were conquered by Aurangzeb's 1686–87 campaign.[8]

Contents

1 Ahmadnagar sultanate

1.1 Rulers

2 Berar sultanate

2.1 Rulers

3 Bidar sultanate

3.1 Rulers

4 Bijapur sultanate

4.1 Rulers

5 Golkonda Sultanate

5.1 Rulers

6 Decline

7 Cultural contributions

7.1 Ahmadnagar sultanate

7.2 Berar sultanate

7.3 Bidar sultanate

7.4 Bijapur sultanate

7.5 Golkonda sultanate

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 External links

Ahmadnagar sultanate

Chand Bibi, an 18th-century painting

The Ahmadnagar sultanate was founded by Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I, who was the son of the Nizam-ul-Mulk Malik Hasan Bahri.[4]:189 Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I was the governor of Junnar, after defeating the Bahmani army led by general Jahangir Khan on May 28, 1490 he declared independence and established the Nizam Shahi dynasty rule over the sultanate of Ahmadnagar. The territory of the sultanate was located in the northwestern Deccan, between the sultanates of Gujarat and Bijapur. Initially his capital was in Junnar. In 1494, the foundation was laid for the new capital Ahmadnagar. Malik Ahmed Shah after several attempts, secured the great fortress of Daulatabad in 1499. After his death in 1510, his son Burhan, a boy of seven was installed in his place. Burhan Shah I died in Ahmadnagar in 1553. He left six sons, of whom Hussain succeeded him. After the death of Hussain Shah I in 1565, his son Murtaza (a minor) ascended the throne. While as a child, his mother Khanzada Humayun Sultana ruled as a regent for several years. Murtaza Shah annexed Berar in 1574. On his death in 1588, his son Miran Hussain ascended the throne. But his reign lasted only a little more than ten months as he was poisoned to death. Ismail, a cousin of Miran Hussain was raised to the throne, but the actual power was in the hands of Jamal Khan, the leader of the Deccani group in the court. Jamal Khan was killed in the battle of Rohankhed in 1591 and soon Ismail Shah was also captured and confined by his father Burhan, who ascended the throne as Burhan Shah. After the death of Burhan Shah his eldest son Ibrahim ascended the throne. Ibrahim Shah died only after a few months in the battle with Bijapur sultanate. Soon, Chand Bibi, the aunt of Ibrahim Shah, proclaimed Bahadur, the infant son Ibrahim Shah as the rightful Sultan and she became the regent of him. In 1596, a Mughal attack led by Murad was repulsed by Chand Bibi. After the death of Chand Bibi in July 1600, Ahmadnagar was conquered by the Mughals and Bahadur Shah was imprisoned. But Malik Ambar and other Ahmadnagar officials defied the Mughals and declared Murtaza Shah II as sultan in 1600 at a new capital, Paranda. Malik Ambar became prime minister and Vakil-us-Saltanat of Ahmadnagar.[9] Later, the capital was shifted first to Junnar and then to a new city Khadki (later Aurangabad). After the death of Malik Ambar, his son Fath Khan surrendered to the Mughals in 1633 and handed over the young Nizam Shahi ruler Hussain Shah, who was sent as a prisoner to the fort of Gwalior. But soon, Shahaji with the assistance of Bijapur, placed an infant scion of the Nizam Shahi dynasty, Murtaza, on the throne and he became regent. In 1636 Aurangzeb, the Mughal viceroy of Deccan finally annexed the sultanate to the Mughal empire after defeating Shahaji.

Rulers

Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I 1490–1510

Burhan Nizam Shah I 1510–1553

Hussain Nizam Shah I 1553–1565

Murtaza Nizam Shah 1565–1588

Miran Nizam Hussain 1588–1589

Isma'il Nizam Shah 1589–1591

Burhan Nizam Shah II 1591–1595

Ibrahim Nizam Shah 1595–1596

Ahmad Nizam Shah II 1596

Bahadur Nizam Shah 1596–1600

Murtaza Nizam Shah II 1600–1610

Burhan Nizam Shah III 1610–1631

Hussain Nizam Shah II 1631–1633

Murtaza Nizam Shah III 1633–1636.[10]

Berar sultanate

The Berar Sultanate was founded by Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk, who was born a Kanarese Hindu, but was captured as a boy by Bahmani forces on an expedition against the Vijayanagara empire and reared as a Muslim.[4] During the disintegration of the Bahmani sultanate, Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk, governor of Berar declared independence in 1490 and founded the Imad Shahi dynasty of the Berar sultanate. He established the capital at Achalpur (Ellichpur). Gavilgad and Narnala were also fortified by him. He was succeeded by his eldest son Ala-ud-din after his death in 1504. In 1528, Ala-ud-din resisted the aggression of Ahmadnagar with the help from Bahadur Shah, sultan of Gujarat. The next ruler, Darya first tried to ally with Bijapur to prevent aggression of Ahmadnagar, but was unsuccessful. Later, he helped Ahmednagar on three occasions against Bijapur. After his death in 1562, his infant son Burhan succeeded him to the throne. But in 1574 Tufal Khan, a minister of Burhan usurped the throne. In the same year Murtaza I, sultan of Ahmadnagar annexed it to his sultanate. Burhan, along with Tufal Khan and his son Shamshir-ul-Mulk were taken to Ahmadnagar and confined to a fortress where all of them subsequently died.[11]

Rulers

Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk 1490–1504

Ala-ud-din Imad Shah 1504–1530

Darya Imad Shah 1530–1562

Burhan Imad Shah 1562–1574

Tufal Khan (usurper) 1574.[11]

Bidar sultanate

Bidar was the smallest of the five Deccan sultanates. Qasim Barid, founder of the Barid Shahi dynasty joined the service of Bahmani ruler Mahmud Shah Bahmani (r.1482–1518) as a sar-naubat but later became mir-jumla of the Bahmani sultanate. In 1492, he became de facto ruler of Bahmani sultanate, though Sultan Mahmud Shah Bahmani remained as the formal ruler. After his death in 1504, his son Amir Barid controlled the administration of the Bahmani sultanate. In 1528, with the flight of the last Bahmani ruler Kalimullah from Bidar, Amir Barid became practically independent. Amir Barid was succeeded by his son Ali Barid, who was the first to assume the title of Shah. He participated in the Battle of Talikota. He was fond of poetry and calligraphy. The last ruler of the Bidar sulatante Amir Barid Shah III was defeated in 1619, and the sultanate was annexed to Bijapur Sultanate.[12]

Rulers

Qasim Barid I 1492–1504

Amir Barid I 1504–1542

Ali Barid Shah 1542–1580

Ibrahim Barid Shah 1580–1587

Qasim Barid Shah II 1587–1591

Ali Barid Shah II 1591

Amir Barid Shah II 1591–1600

Mirza Ali Barid Shah III 1600–1609

Amir Barid Shah III 1609–1619.[10]

Bijapur sultanate

Ibrahim Adil Shah II

The Bijapur sultanate was ruled by the Adil Shahi dynasty from 1490 to 1686. The Adil Shahis were originally provincial rulers of the Bahmani Sultanate, but with the break-up of the Bahmani state after 1518, Ismail Adil Shah established an independent sultanate, becoming one of the five Deccan sultanates.

The Bijapur sultanate was located in southwestern India, straddling the Western Ghats range of southern Maharashtra and northern Karnataka. Ismail Adil Shah and his successors embellished the capital at Bijapur with numerous monuments.

The Adil Shahis fought the empire of Vijayanagar, which lay to the south across the Tungabhadra River, and fought the other sultanates as well. The sultanates combined forces to deliver a decisive defeat to Vijayanagar in 1565, after which the empire broke up. Bijapur seized control of the Raichur Doab from Vijayanagar. In 1619, the Adil Shahis conquered the neighbouring sultanate of Bidar, which was incorporated into their realm. In the 17th century, the Marathas revolted successfully under Shivaji's leadership and captured major parts of the Sultanate like Bijapur. The weakened Sultanate was conquered by Aurangzeb in 1686 with the fall of Bijapur, bringing the dynasty to an end.

Rulers

Yusuf Adil Shah 1490–1510

Ismail Adil Shah 1510–1534

Mallu Adil Shah 1534–1535

Ibrahim Adil Shah I 1535–1558

Ali Adil Shah I 1558–1580

Ibrahim Adil Shah II 1580–1627

Mohammed Adil Shah 1627–1656

Ali Adil Shah II 1656–1672

Sikandar Adil Shah 1672–1686.[10]

Golkonda Sultanate

A manuscript depicting the painting of Abul Hasan Qutb Shah the last ruler of the Golkonda Sultanate.

The dynasty's founder, Sultan Quli Qutub-ul-Mulk, migrated to Delhi from Persia with some of his relatives and friends in the beginning of the 16th century. Later he migrated south to Deccan and served Bahmani Sultan Mohammad Shah. He conquered Golkonda and became the Governor of the Telangana region in 1518, after the disintegration of the Bahmani sultanate. Soon after, he declared independence from the Bahmani sultanate, took title Qutb Shah, and established Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda. The dynasty ruled for 171 years, until the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb's army besieged and conquered Golkonda in 1687.

Rulers

Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk 1518–1543

Jamsheed Quli Qutb Shah 1543–1550

Subhan Quli Qutb Shah 1550

Ibrahim Quli Qutub Shah 1550–1580

Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah 1580–1611

Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah 1611–1626

Abdullah Qutb Shah 1626–1672

Abul Hasan Qutb Shah 1672–1687.[13]

Decline

Cultural contributions

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

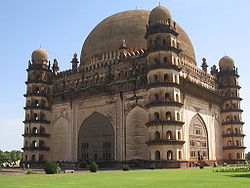

Gol Gumbaz (Bijapur Sultanate)

Tomb of Salabat Khan II (Ahmednagar Sultanate)

Al-Buraq, by unknown, 1770-1775, Deccan School.[15]

The rulers of the Deccan sultanates had a number of cultural contributions to their credit in the fields of art, music, literature and architecture.

An important cultural contribution of the Deccan sultanates is the development of the Dakhani language. Dakhani, which started growing under the Bahamani rulers, developed into an independent spoken and literary language during this period by continuously drawing resources from Arabic-Persian, Marathi, Kannada and Telugu. This language later became known as Dakhani Urdu to distinguish it from the North Indian Urdu. The Deccani miniature painting, which flourished in the courts of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golkonda is another major cultural contribution of the Deccan Sultantaes.[16] The architectural splendors of Deccan like Char Minar and Gol Gumbaz belong to this period. The religious tolerance displayed by the Nizam Shahi, Adil Shahi and Qutb Shahi rulers is also worthy of mention.

Ahmadnagar sultanate

The Nizam Shahi rulers of Ahmadnagar enthusiastically patronised miniature painting. The earliest surviving paintings are found as the illustrations of a manuscript Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi (c.1565), which is now in Bharata Itihasa Samshodhaka Mandala, Pune. A miniature painting of Murtaza Nizam Shah (c.1575) is in the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris while another one is in State Library in Rampur. Three other paintings, The Running Elephant is in an American private collection, The Royal Picnic in the India Office Library in London and the Young Prince Embraced by a Small Girl in the Edwin Binney 3rd Collection of South Asian Works in the San Diego Museum, most likely belonging to the Burhan Nizam Shah II period.[17]

Amongst the monuments of Nizam Shahi rulers in Ahmadnagar, the earliest one is the tomb of Ahmad Shah I Bahri (1509) at the centre of Bagh Rouza, a garden complex. The Jami Masjid also belong to the same period. Mecca Masjid, built in 1525 by Rumi Khan, a Turkish artillery officer of Burhan Nizam Shah I has originality in its design. The Kotla complex constructed in 1537 as a religious educational institution. The impressive Farah Bagh was the centrepiece of a huge palacial complex completed in 1583. The other monuments in Ahmednagar of the Nizam Shahi period are Do Boti Chira (tomb of Sharja Khan, 1562), Damri Masjid (1568) and the tomb of Rumi Khan (1568). The Jami Masjid (1615) In Khirki (Aurangabad) and the Chini Mahal inside the Daulatabad fort were constructed during the late Nizam Shahi period (1600–1636). The tomb of Malik Ambar in Khuldabad (1626) is another impressive monument of this period. The Kali Masjid of Jalna (1578) and the tomb of Dilawar Khan (1613) in Rajgurunagar also belong to the Nizam Shahi period.[18][19]

During the reign of Ahmad Shah I Bahri, his keeper of imperial records, Dalapati wrote an encyclopaedic work, the Nrisimha Prasada, where he mentioned his overlord as Nizamsaha. It is a notable instance of the religious tolerance of the Nizam Shahi rulers.[20]

Berar sultanate

The ruined palace of Hauz Katora, 3 km. west of Achalpur is the only notable surviving Imad Shahi monument.[21]

Bidar sultanate

Bidriware water-pipe base, ca. 18th century, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The main architectural activities forthe Barid Shahi rulers were the garden tombs. The tomb of Ali Barid Shah (1577) is the most notable monument in Bidar. The tomb consists of a lofty domed chamber, open on four sides located in the middle of a Persian four-square garden. The Rangin Mahal in Bidar, built during the reign of Ali Barid Shah is a complete and exquisitely decorated courtly structure. Other important monuments in Bidar during this period are tomb of Qasim II and Kali Masjid.[22]

An important class of metalwork known as Bidri originated from Bidar. These metalwork were carried out on black metal mainly zinc, which were inlaid with designs of silver and brass and sometimes copper.[23]

Bijapur sultanate

Gol Gumbaz, mausoleum of Mohammed Adil Shah

The Adil Shahi rulers contributed greatly in the fields of art, architecture, literature and music. Bijapur developed into a cosmopolitan city, and it attracted many scholars, artists, musicians, and Sufi saints from Rome, Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Turkestan.

Amongst the major architectural works in Bijapur sultanate, one of the earliest is the unfinished Jami Masjid (started by Ali Adil Shah I in 1576). It has an arcaded prayer hall with fine aisles supported on massive piers and has an impressive dome. One of the most impressive monuments built during the reign of Ibrahim II was the Ibrahim Rouza which was originally planned as a tomb for queen Taj Sultana but later converted into the tomb for Ibrahim Adil Shah II and his family. This complex, completed in 1626, consists of a paired tomb and a mosque. Ibrahim II also planned to construct a new twin city to Bijapur, Nauraspur. The construction began in 1599 but never completed. The greatest monument in Bijapur is the Gol Gumbaz, the mausoleum of Muhammad Adil Shah. The diameter of the hemispherical dome is 44 meters externally. This monument was completed in 1656. The other important architectural works of this period are the Chini Mahal, the Jal Mandir, the Sat Manzil, the Gagan Mahal, the Anand Mahal and the Asar Mahal (1646) in Bijapur, Kummatgi (16 km from Bijapur), the Panhala fort and Naldurg (45 km. from Solapur).[24]

Persian artists of Adil Shahi court have left a rare treasure of miniature paintings, some of which are well-preserved in Europe's museums. The earliest miniature paintings are ascribed to the period of reign of Ali Adil Shah I. The most significant of them are the paintings in the manuscript of Nujum-ul-Ulum (Stars of Science) (1570), kept in Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. The manuscript consists about 400 miniature paintings. Two other illustrated manuscripts which can be attributed to the period of Ali Adil Shah I are Jawahir-al Musiqat-i-Muhammadi in the British Library which contains 48 paintings and a Marathi commentary of Sarangadeva’s Sangita Ratnakara kept in the museum of City Palace, Jaipur which contains 4 paintings. The maximum number of miniature paintings came down to us belong to the period of reign of Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II. One of the most celebrated painters of his court was Maulana Farrukh Hussain. The miniature paintings of this period are preserved in the Bikaner Palace; the Bodleian Library in Oxford; the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum in London; the Muśee Guimet in Paris; the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersberg; and the Náprstek Museum in Prague.[25]

Under the Adil Shahi rulers many literary works were published in Dakhani. Ibrahim Adil Shah II himself wrote a book of songs, Kitab-i-Nauras in Dakhani. This book contains a number of songs whose tunes are set to different ragas and raginis. In his songs, he praised Hindu goddess Sarasvati along with the Prophet and Sufi saint Hazrat Khwaja Banda Nawaz Gesudaraz. A unique tambur (lute) known as Moti Khan was in his possession. The famous Persian poet laureate Zuhuri was his court poet. The Mushaira (poetic symposium) was born in the Bijapur court and later travelled north.

The Adil Shahi kings were known for tolerance towards Hindus and non-interference in their religious matters. They employed Hindus to high posts, especially as the officers who deal with the accounts and the administration, since the documents pertaining to the both were maintained in Marathi.

Golkonda sultanate

The Charminar built by Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah is a centerpiece of Hyderabad and one of the most important examples of Indo-Islamic architecture.

Abdullah Qutb Shah on a Terrace with Attendants, c. 18th century.

One of the earliest architectural achievements of the Qutb Shahi dynasty is the fortified city of Golkonda, which is now in ruins. The nearby Qutb Shahi tombs are also noteworthy.[14] In the 16th century Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah decided to shift the capital to Hyderabad, 8 kilometers east of Golconda. Here, he constructed the most original monument in the Deccan, the Charminar in the heart of the new city.[14] This monument (completed in 1591) has four minarets which were 56 meters high. The construction of the Mecca Masjid, located at the immediate south of Charminar was started in 1617 during the reign of Muhammad Qutb Shah but completed only in 1693. The other important monuments of this period are the Toli Masjid, Shaikpet Sarai, Khairtabad Mosque, Taramati Baradari, Hayat Bakshi Mosque, and the Jama Masjid at Gandikota.[26]

The Qutb Shahi rulers were great patrons of literature and invited many scholars, poets, historians and Sufi saints from Iran to settle in their sultanate. The sultans patronized literature in Persian as well as Telugu, the local language. However, the most important contribution of the Golkonda sultanate in the field of literature is the development of the Dakhani language. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah was not only a great patron of art and literature but also a poet of high order. He wrote in Dakhani, Persian and Telugu and left an extensive Diwan (collection of poetry) in Dakhani, known as Kulliyat-i-Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah. Apart from the praise of God and the Prophet, he also wrote on nature, love and contemporary social life. Kshetrayya and Bhadrachala Ramadasu are some notable Telugu poets of this period.[27]

The Qutb Shahi rulers were much more liberal than their other Muslim counterparts. During the reign of Abdullah Qutb Shah in 1634 CE, the ancient Indian sex manual Koka Shastra was translated into Persian named Lazzat-un-Nisa (Flavors of the Woman).[28]

The Qutb Shahi rulers invited many Persian artists like Shaykh Abbasi and Muhammad Zaman in their court, which left a profound impact of different phases of Iranian art on the miniature paintings of this period. The earliest miniature paintings like the 126 illustrations in the manuscript of Anwar-i-Suhayli (c. 1550–1560) in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The illustrationsSindbad Namah in the India Office Library and Shirin and Khusrau in the Khudabaksh Library in Patna most probably belong to the period of reign of Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah. The 5 illustrations in a manuscript of the Diwan-i-Hafiz (c.1630) in the British Museum, London belonged to the period of reign of Abdullah Qutb Shah. The most outstanding surviving Golkonda painting probably is the Procession of Sultan Abdullah Qutb Shah Riding an Elephant (c. 1650) in the Saltykov-Shtshedrine State Public Library in St. Petersberg.[29] Their painting style lasted even after the dynasty was extinct. It evolved into the Hyderabad style.

Qutb Shahi rulers appointed Hindus in important administrative posts. Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah appointed Murari Rao as Peshwa, second to only Mir Jumla (prime minister).

See also

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

Notes

^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, p.269

^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan,

ISBN 81-7276-407-1, p.412

^ abc Ferishta, Mahomed Kasim (1829). History of the Rise of the Mahometan Power in India, till the year A.D. 1612 Volume III. Translated by Briggs, John. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

^ Bosworth 1996, p. 324.

^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. p. 101.

^ Ahmed, Farooqui Salma (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. p. 177.

^ "500 years of Deccan history fading away due to neglect".

^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.)(2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan,

ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp.415–45

^ abc Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, p.274

^ ab Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan,

ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp.463–6

^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan,

ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp.466–8

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, p.275

^ abc Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Qutb Shahi Monuments of Hyderabad Golconda Fort, Qutb Shahi Tombs, Charminar – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

^ "Nauras: The Many Arts of the Deccan". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

^ "Deccani painting". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.145–151.

^ Sohoni, Pushkar (2010). "Local Idioms and Global Designs: Architecture of the Nizam Shahs" (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania).

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.80–86.

^ Bhattacharya, D.C. (1962). The Nibandhas in S. Radhakrishnan (ed.) The Cultural Heritage in India, Vol.II, Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture,

ISBN 81-85843-03-1, p.378

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, p. 41.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, p.14 & pp.77–80.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.239–240.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp. 41–47 & pp.86–98.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.161–190.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.47–53 & pp.101–106.

^ Nanisetti, Serish (2006-04-14). "Long long ago when faith moved a king". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

^ Akbar, Syed (2019-01-05). "Lazzat-Un-Nisa: Hyderabad's own Kamasutra back in focus - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

^ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999,

ISBN 0-521-56321-6, pp.47–53 & pp.191–210.

References

Majumdar, R.C. (2006). The Delhi Sultanate. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

Majumdar, R.C. (2007). The Mughul Empire. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

ISBN 81-7276-407-1.

Mitchell, George; Mark Zebrowski (1999). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56321-6.

- Chopra, R.M., The Rise, Growth And Decline of Indo-Persian Literature, 2012, Iran Culture House, New Delhi. Revised edition published in 2013.

External links

- A website on Bijapur Sultanate

- Monuments of Deccan Sultanates and other Islamic Monuments of India

- http://www.travelblog.org/Asia/blog-380811.html