Giro di Lombardia

| |

| Race details | |

|---|---|

| Date | Early October |

| Region | Lombardy, Italy |

| English name | Tour of Lombardy |

| Local name(s) | Giro di Lombardia Il Lombardia |

| Nickname(s) | La classica delle foglie morte (in Italian) Race of the Falling Leaves (in English) |

| Discipline | Road |

| Competition | UCI World Tour |

| Type | One-day Classic |

| Organiser | RCS Sport |

| Race director | Michele Acquarone |

| History | |

| First edition | 1905 (1905) |

| Editions | 112 (as of 2018) |

| First winner | |

| Most wins | (5 wins) |

| Most recent | |

The Giro di Lombardia (English: Tour of Lombardy), officially Il Lombardia , is a cycling race in Lombardy, Italy.[1] It is traditionally the last of the five 'Monuments' of the season, considered to be one of the most prestigious one-day events in cycling, and one of the last events on the UCI World Tour calendar. Nicknamed the Classica delle foglie morte ("the Classic of the falling (dead) leaves"), it is the most important Autumn Classic in cycling. The race's most famous climb is the Madonna del Ghisallo in the race finale.

The first edition was held in 1905. Since its creation, the Giro di Lombardia has been the classic with the fewest number of interruptions in cycling; only the editions of 1943 and 1944 were cancelled for reasons of war. Italian Fausto Coppi won a record five times.

Because of its demanding course, the race is considered a climbers classic, favouring climbers with a strong sprint finish.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Milan–Milan

1.2 Race of the Champions

1.3 The Autumn Classic

2 Route

2.1 Course changes

2.2 Race characteristics

2.3 Significant climbs

2.4 Start and finish places

3 Winners

3.1 Multiple winners

3.2 Wins per country

4 Trittico di Autunno

5 Milan–San Remo and Tour of Lombardy Double

5.1 Tripletta

6 References

7 External links

History

Milan–Milan

The Tour of Lombardy was created as an idea of journalist Tullo Morgagni. Morgagni wanted to give Milanese rider Pierino Albini the opportunity to take revenge for his defeat against Giovanni Cuniolo in the short-lived Italian King's Cup. His newspaper la Gazzetta dello Sport organized a new race as a 'rematch' on 12 November 1905, called Milano–Milano. The race attracted vast crowds along the course and ended in Milan with the victory of Giovanni Gerbi, at the time one of the stars of cycling. Gerbi won the race 40 minutes ahead of Giovanni Rossignoli and Luigi Ganna.[2]

Frenchman Henri Pélissier won the 1911 Giro di Lombardia in the sprint.

The race soon became a fixture as the closing race of the Italian and European cycling season. It was renamed Giro di Lombardia in 1907. After the pioneering years, the race was dominated alternately by Frenchman Henri Pélissier and local heroes Gaetano Belloni and Costante Girardengo, all winning the race three times.

Race of the Champions

Record winner Fausto Coppi won the race five times between 1946 and 1954.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, Alfredo Binda, Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi, icons of Italian cycling, were the main protagonists and immortalized the race with their exploits. Coppi won the race 5 times (of which 4 consecutive wins) and Binda 4 times. Coppi finished solo on every win, following a successful strategy of attacking on the Madonna del Ghisallo and maintaining his lead to the finish in Milan. Gino Bartali was the king of the podium with 9 top-3 finishes (3 wins, 4 second places and 2 third places).

The race of 1956 was a particularly fascinating battle. At 60 km from the finish a breakaway was formed with Fausto Coppi, seeking his sixth victory. Italian rider Fiorenzo Magni had missed the break, and as he fell further behind, a car passed him with Giulia Occhini, Coppi's infamous mistress, sitting in the back. The two did not get on and as her car passed, Magni saw her sneer at him. Infuriated, Magni set out in an improbable solo pursuit of the breakaway and caught the leaders in the final kilometres. He and Coppi openly argued and André Darrigade, sensing their indecisiveness, attacked to claim the victory, thereby relegating Coppi and Magni to second and third place.[3]

In 1961, the finish of the Tour of Lombardy was moved from Milan to Como and the identity of the race changed fundamentally. The previous flat finale towards the finish in Milan was replaced with a spectacular finish by Lake Como, just 6 km after the top of the last climb. Despite an occasional return to finishing in Milan, the race had developed a new personality, defined by a series of arduous climbs amid a mountainous scenery.[4]

Over the years the race has been dominated mainly by Italian riders. Frenchman Henri Pelissier and Ireland's Sean Kelly were the only non-Italian riders to win the race three times. Cycling legend Eddy Merckx won three consecutive victories from 1971 to 1973, but his last win was stripped after a positive doping test and awarded to second-place finisher Felice Gimondi.[5]

The race of 1974 gave birth to another memorable anecdote. Eddy Merckx wanted to get his revenge, but fellow Belgian Roger De Vlaeminck attacked early in the race, inducing Merckx to make his team work in pursuit. De Vlaeminck, not really intending to go solo, stopped and hid behind a bush to let the peloton pass. He rode back to the front of the peloton and jokingly asked a baffled Merckx who they were chasing. De Vlaeminck won the race ahead of Merckx.[6]

The Autumn Classic

For nearly 70 years the race was called "il Mondiale d'Autunno" in Italy ("the World Championship of Autumn"), as the real World Championship was held at the end of summer. It lost this particular role in 1995 when the UCI revolutionized the international cycling calendar and moved the World Championship from August to October, one week before the Giro di Lombardia.

From 1988 to 2004 the Tour of Lombardy was the final leg of the UCI Road World Cup and was often the decisive race in that competition. In 1997 Michele Bartoli needed to finish ahead of Rolf Sørensen in the race to be the winner of the 1997 World Cup. For 30 km he did solo work in a four-man breakaway, so sacrificing his chances to win the sprint. The edition was won by Frenchman Laurent Jalabert, Bartoli finished fourth and won the World Cup.[7]

Vincenzo Nibali won the 2015 and 2017 Giro di Lombardia.

The race had become the most important Autumn Classic together with Paris–Tours in France, which was mainly won by sprinters or escapees. By the early 21st century however, Paris–Tours lost its status as a World Tour race, and the Tour of Lombardy was the one remaining major Classic in autumn, the only Monument in the latter part of the year. Damiano Cunego imposed himself as the Lord of Lombardy with three victories.

In 2006, the race celebrated its 100th edition, won by Paolo Bettini, one week after becoming world champion. The edition was particularly emotional because Bettini's brother had died in a car accident just five days before the race, and the Italian was overcome with emotion when he crossed the finish line.[8] Bettini is one of seven riders to win the Tour of Lombardy after becoming world champion earlier the same year. The other six are Alfredo Binda, Tom Simpson, Eddy Merckx, Felice Gimondi, Giuseppe Saronni and Oscar Camenzind.

Since 2012 both the World Championship and the Giro di Lombardia have a new, earlier date on the calendar at the end of September, and the name officially became Il Lombardia. It was the beginning of a remarkable revival for the Monument race. The Tour of Lombardy is now the classic par excellence for riders to take revenge for the world championship or to achieve an "Autumn Double win". In recent years Philippe Gilbert, Joaquim Rodríguez and Vincenzo Nibali all won the race twice.

Route

Church of "Madonna del Ghisallo".

Like most of cycling's classics, the route has developed over the years, and the Tour of Lombardy has undergone more changes than any other cycling monument. Since the 1960s it has been notable for its hilly and varied course around Lake Como, to the northeast of Milan, with a flat finish in one of the cities on the shores of the lake.

Its signature symbol is the climb of the Madonna del Ghisallo, one of the iconic sanctuaries in cycling. The climb starts near Bellagio at the shore of the Como Lake, and heads up until the church of Madonna del Ghisallo (754m), the patroness of cyclists. Over the years, it has become indelibly linked with the race and with cycling in general. It was the favourite climb of cycling greatnesses Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali, who immortalized it. The church also serves as a museum containing religious and cycling-related objects.[9]

Course changes

Originally the Tour of Lombardy was raced from Milan to Milan, and like many cycling classics, climbs were gradually introduced to the course, in a bid to make the race more demanding. In 1961, the finish was moved to Como and the character of the race changed fundamentally. The long and flat run-in to the finish in Milan was abandoned; in its place came a mountainous lake-side finish, just 6 km from the top of the last climb. The route usually has some changes every year, sometimes a complete restyling, only to be altered again the next edition.

Route of the 2008 edition

From 1984 to 1989 the finish returned to Milan and in 1990 to its suburb Monza, inviting attackers for long-distance breakaways. From 1995 to 2003 the finish was in Bergamo, with the Colle del Gallo (Col Gàl in Bergamasque) as the last climb of the day. The Colle del Gallo, with its sanctuary of the Madonna dei ciclisti at the top, often proved to be decisive.

In 2004, after twenty years, the finish returned to the lakefront in Como, with the short but steep San Fermo della Battaglia climb just before the arrival. The 2010 edition saw the re-introduction of the Muro di Sormano, a spectacular climb with a maximum gradient of 25%, which replaced the Civiglio after the Ghisallo.[10]

In 2011 the route was fully renewed, with a first-time finish in Lecco. The Sormano was included again, but was climbed before the Ghisallo. After the Ghisallo, a flat stretch led to the final climb of the race: the steep Villa Vergano in Galbiate. After the descent only 3 km remained until the finish in Lecco. The 3,4 km climb of Villa Vergano was the decisive site in the 2011 and 2012 edition.[11]

In 2014 the finish was moved to Bergamo. Organizer RCS announced that from 2014 to 2017 the finish of the Tour of Lombardy will alternate between Bergamo and Como.

Race characteristics

The Giro di Lombardia is considered a climbers classic and one of the most arduous races of the season, because of its distance (ca. 255 km) and several famous climbs. Nowadays the route usually features five or six significant climbs. The best-known of them is the Madonna del Ghisallo, one of the few fixed locations of the race. The climb is 10,6 kilometres long, with an average gradient of 5.2% and stretches of over 10%.

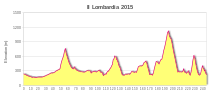

Profile of the 2015 Tour of Lombardy

Because the race usually has a downhill or flat run-in to the finish, the main contenders are riders with a broad range of skills. As such, the course favours climbers with a strong sprint finish and even Grand Tour specialists. Time trial specialist Tony Rominger won the Tour of Lombardy twice in the 1990s and Tour de France winner Vincenzo Nibali won the 2015 edition after a downhill attack on the penultimate descent.[12][13] The race is often compared to Liège–Bastogne–Liège, the monument race in Belgium earlier in the year. Both classics have a similar hilly course and show a similar palmarès since the 1960s, but are different in character. The hills in Lombardy are usually longer than those in the Belgian Ardennes and are more spread out over the course. Liège–Bastogne–Liège has 12 categorized climbs, usually shorter and steeper, coming in faster succession than in the Tour of Lombardy, and has an uphill-finish.[14]

Panoramic view of Lake Como with Bellagio at the foot of the Ghisallo

Because of its position in autumn as one of the last classics of the year, the race is commonly nicknamed the Race of the Falling Leaves. Consequently, the weather repeatedly plays a decisive role in the nature of the race. In bad weather - common to mountainous Lombardy - the race is often a grueling contest where the strongest riders attack well ahead of the finish. The editions of 2006 and 2010 were exceptionally rainy. In 2010 Philippe Gilbert and Michele Scarponi attacked with 40 km to go; Gilbert distanced Scarponi on the San Fermo della Battaglia and won the race.

When the weather conditions are good, teams are able to control the race more easily and decisive attacks come later in the race. On sunny days, the leaves on the trees typically blaze a golden trail around Lombardy, and TV coverage displays extensive aerial footage of the scenery around the Como Lake. The Italian press, never shy to introduce a poetic epithet, has also coined the phrase The Romantic Classic to denote the race.[4]

Significant climbs

An overview of climbs featured in the Giro di Lombardia. As the course changes every year, not all climbs are included in the same edition.

| Climb | Distance | Average Grade | Max Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civiglio | 5,7 km | 6,9% | 10% |

| Colle Brianza | 4,2 km | 6,9% | 7,5% |

| Colma di Sormano | 9,6 km | 6,5% | 8,4% |

| Colle del Gallo | 6 km | 6,8% | 10,4% |

| Madonna del Ghisallo | 10,6 km | 5,2% | 11% |

| Climb | Distance | Average Grade | Max Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muro di Sormano | 1,7 km | 17% | 25% |

| San Fermo della Battaglia | 2,2 km | 8,2% | 8,3% |

| Valcava | 11,8 km | 8% | 12% |

| Villa Vergano | 3,2 km | 7,4% | 15% |

Start and finish places

| Years | Start | Finish |

|---|---|---|

| 1905–1960 | Milano | Milano |

| 1961–1984 | Milano | Como |

| 1984–1989 | Como | Milano (Duomo) |

| 1990–1994 | Milano | Monza |

| 1995–2001 | Varese | Bergamo |

| 2002 | Cantu | Bergamo |

| 2003 | Como | Bergamo |

| 2004–2006 | Como | |

| 2007–2009 | Varese | Como |

| 2010 | Milano | Como |

| 2011 | Milano | Lecco |

| 2012–2013 | Bergamo | Lecco |

| 2014, 2016 | Como | Bergamo |

| 2015, 2017 | Bergamo | Como |

Winners

| Rider | Team | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1905 | Giovanni Gerbi (ITA) | Maino | ||

1906 | Cesare Brambilla (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1907 | Gustave Garrigou (FRA) | Peugeot–Wolber | ||

1908 | François Faber (LUX) | Peugeot–Wolber | ||

1909 | Giovanni Cuniolo (ITA) | Rudge | ||

1910 | Giovanni Micheletto (ITA) | Stucchi | ||

1911 | Henri Pélissier (FRA) | – | ||

1912 | Carlo Oriani (ITA) | Stucchi | ||

1913 | Henri Pélissier (FRA) | Alcyon–Soly | ||

1914 | Lauro Bordin (ITA) | Bianchi–Dei | ||

1915 | Gaetano Belloni (ITA) | – | ||

1916 | Leopoldo Torricelli (ITA) | Maino | ||

1917 | Philippe Thys (BEL) | Peugeot–Wolber | ||

1918 | Gaetano Belloni (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1919 | Costante Girardengo (ITA) | Stucchi–Dunlop | ||

1920 | Henri Pélissier (FRA) | J.B. Louvet | ||

1921 | Costante Girardengo (ITA) | Stucchi–Pirelli | ||

1922 | Costante Girardengo (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1923 | Giovanni Brunero (ITA) | Legnano–Pirelli | ||

1924 | Giovanni Brunero (ITA) | Legnano–Pirelli | ||

1925 | Alfredo Binda (ITA) | Legnano–Pirelli | ||

1926 | Alfredo Binda (ITA) | Legnano–Pirelli | ||

1927 | Alfredo Binda (ITA) | Legnano–Pirelli | ||

1928 | Gaetano Belloni (ITA) | Wolsit–Pirelli | ||

1929 | Pietro Fossati (ITA) | Maino–Clément | ||

1930 | Michele Mara (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1931 | Alfredo Binda (ITA) | Legnano–Hutchinson | ||

1932 | Antonio Negrini (ITA) | Maino–Clément | ||

1933 | Domenico Piemontesi (ITA) | Génial Lucifer–Hutchinson | ||

1934 | Learco Guerra (ITA) | Maino–Clément | ||

1935 | Enrico Mollo (ITA) | Gloria | ||

1936 | Gino Bartali (ITA) | Legnano–Wolsit | ||

1937 | Aldo Bini (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1938 | Cino Cinelli (ITA) | Frejus | ||

1939 | Gino Bartali (ITA) | Legnano | ||

1940 | Gino Bartali (ITA) | Legnano | ||

1941 | Mario Ricci (ITA) | Legnano | ||

1942 | Aldo Bini (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

| 1943 | No race | |||

| 1944 | No race | |||

1945 | Mario Ricci (ITA) | Legnano | ||

1946 | Fausto Coppi (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1947 | Fausto Coppi (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1948 | Fausto Coppi (ITA) | Bianchi | ||

1949 | Fausto Coppi (ITA) | Bianchi–Ursus | ||

1950 | Renzo Soldani (ITA) | Thomann | ||

1951 | Louison Bobet (FRA) | Stella–Dunlop | ||

1952 | Giuseppe Minardi (ITA) | Legnano | ||

1953 | Bruno Landi (ITA) | Fiorelli | ||

1954 | Fausto Coppi (ITA) | Bianchi–Pirelli | ||

1955 | Cleto Maule (ITA) | Torpado | ||

1956 | André Darrigade (FRA) | Bianchi–Pirelli | ||

1957 | Diego Ronchini (ITA) | Bianchi–Pirelli | ||

1958 | Nino Defilippis (ITA) | Carpano | ||

1959 | Rik Van Looy (BEL) | Faema–Guerra | ||

1960 | Emile Daems (BEL) | Philco | ||

1961 | Vito Taccone (ITA) | Atala | ||

1962 | Jo de Roo (NED) | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | ||

1963 | Jo de Roo (NED) | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | ||

1964 | Gianni Motta (ITA) | Molteni | ||

1965 | Tom Simpson (GBR) | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | ||

1966 | Felice Gimondi (ITA) | Salvarani | ||

1967 | Franco Bitossi (ITA) | Filotex | ||

1968 | Herman van Springel (BEL) | Dr. Mann–Grundig | ||

1969 | Jean-Pierre Monseré (BEL) | Flandria–De Clerck–Krüger | ||

1970 | Franco Bitossi (ITA) | Filotex | ||

1971 | Eddy Merckx (BEL) | Molteni | ||

1972 | Eddy Merckx (BEL) | Molteni | ||

1973 | Felice Gimondi (ITA) | Bianchi–Campagnolo | ||

1974 | Roger De Vlaeminck (BEL) | Brooklyn | ||

1975 | Francesco Moser (ITA) | Filotex | ||

1976 | Roger De Vlaeminck (BEL) | Brooklyn | ||

1977 | Gianbattista Baronchelli (ITA) | Scic | ||

1978 | Francesco Moser (ITA) | Sanson–Campagnolo | ||

1979 | Bernard Hinault (FRA) | Renault–Gitane | ||

1980 | Fons De Wolf (BEL) | Boule d'Or–Studio Casa | ||

1981 | Hennie Kuiper (NED) | DAF Trucks–Côte d'Or | ||

1982 | Giuseppe Saronni (ITA) | Del Tongo | ||

1983 | Sean Kelly (IRL) | Sem–Reydel–Mavic | ||

1984 | Bernard Hinault (FRA) | La Vie Claire | ||

1985 | Sean Kelly (IRL) | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | ||

1986 | Gianbattista Baronchelli (ITA) | Supermercati Brianzoli | ||

1987 | Moreno Argentin (ITA) | Gewiss–Bianchi | ||

1988 | Charly Mottet (FRA) | Système U–Gitane | ||

1989 | Tony Rominger (SUI) | Chateau d'Ax | ||

1990 | Gilles Delion (FRA) | Helvetia–La Suisse | ||

1991 | Sean Kelly (IRL) | PDM–Concorde | ||

1992 | Tony Rominger (SUI) | Ariostea | ||

1993 | Pascal Richard (SUI) | CLAS–Cajastur | ||

1994 | Vladislav Bobrik (RUS) | Gewiss–Ballan | ||

1995 | Gianni Faresin (ITA) | Lampre–Panaria | ||

1996 | Andrea Tafi (ITA) | Mapei–GB | ||

1997 | Laurent Jalabert (FRA) | ONCE | ||

1998 | Oscar Camenzind (SUI) | Mapei–Bricobi | ||

1999 | Mirko Celestino (ITA) | Team Polti | ||

2000 | Raimondas Rumšas (LTU) | Fassa Bortolo | ||

2001 | Danilo Di Luca (ITA) | Cantina Tollo–Acqua e Sapone | ||

2002 | Michele Bartoli (ITA) | Fassa Bortolo | ||

2003 | Michele Bartoli (ITA) | Fassa Bortolo | ||

2004 | Damiano Cunego (ITA) | Saeco Macchine per Caffè | ||

2005 | Paolo Bettini (ITA) | Quick-Step–Innergetic | ||

2006 | Paolo Bettini (ITA) | Quick-Step–Innergetic | ||

2007 | Damiano Cunego (ITA) | Lampre–Fondital | ||

2008 | Damiano Cunego (ITA) | Lampre | ||

2009 | Philippe Gilbert (BEL) | Silence–Lotto | ||

2010 | Philippe Gilbert (BEL) | Omega Pharma–Lotto | ||

2011 | Oliver Zaugg (SUI) | Leopard Trek | ||

2012 | Joaquim Rodríguez (ESP) | Team Katusha | ||

2013 | Joaquim Rodríguez (ESP) | Team Katusha | ||

2014 | Daniel Martin (IRL) | Garmin–Sharp | ||

2015 | Vincenzo Nibali (ITA) | Astana | ||

2016 | Esteban Chaves (COL) | Orica–BikeExchange | ||

2017 | Vincenzo Nibali (ITA) | Bahrain–Merida | ||

2018 | Thibaut Pinot (FRA) | Groupama–FDJ | ||

Multiple winners

| Wins | Rider | Nationality | Editions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Fausto Coppi | 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1954 | |

| 4 | Alfredo Binda | 1925, 1926, 1927, 1931 | |

| 3 | Henri Pélissier | 1911, 1913, 1920 | |

| Costante Girardengo | 1919, 1921, 1922 | ||

| Gaetano Belloni | 1915, 1918, 1928 | ||

| Gino Bartali | 1936, 1939, 1940 | ||

| Seán Kelly | 1983, 1985, 1991 | ||

| Damiano Cunego | 2004, 2007, 2008 | ||

| 2 | Giovanni Brunero | 1923, 1924 | |

| Aldo Bini | 1937, 1942 | ||

| Mario Ricci | 1941, 1945 | ||

| Jo de Roo | 1962, 1963 | ||

| Franco Bitossi | 1967, 1970 | ||

| Eddy Merckx | 1971, 1972 | ||

| Felice Gimondi | 1966, 1973 | ||

| Roger De Vlaeminck | 1974, 1976 | ||

| Francesco Moser | 1975, 1978 | ||

| Bernard Hinault | 1979, 1984 | ||

| Gianbattista Baronchelli | 1977, 1986 | ||

| Tony Rominger | 1989, 1992 | ||

| Michele Bartoli | 2002, 2003 | ||

| Paolo Bettini | 2005, 2006 | ||

| Philippe Gilbert | 2009, 2010 | ||

| Joaquim Rodríguez | 2012, 2013 | ||

| Vincenzo Nibali | 2015, 2017 |

Wins per country

| Wins | Country |

|---|---|

| 69 | |

| 12 | |

| 12 | |

| 5 | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 |

Trittico di Autunno

The Trittico di Autunno (Autumn Triptych) is an unofficial trio of cycling classics held in the Lombardy and Piedmont regions of Northern Italy, in early October. Three one-day races, Milano–Torino, the Giro del Piemonte (Tour of Piedmont) and the Tour of Lombardy, are held within a four-day timeframe in the week following the World Championship. Milan-Turin is held on the Thursday after the World Championship, the Giro del Piemonte on Friday and the Tour of Lombardy is the closing race on Sunday. The Tour of Lombardy is the pinnacle, the hardest and unequivocally most important race of this unofficial trio.

All three races have a rich history, dating back more than a century. Milan-Turin, with its first running in 1876, is the oldest classic in the world, three decades older than the Tour of Lombardy. Until 1986, and again from 2005 to 2007, Milan-Turin was organized in the spring. Since 1987 the three races are held as an "Autumn Trio", initially mid-October and since 2012 two weeks earlier. Both Milan-Turin and the Giro del Piemonte have suffered some continuity problems in the past, but are on back on the calendar of 2015.[15] For many, particularly Italian riders, Milan-Turin and the Giro del Piemonte (both 200-km races) are the ultimate races to prepare for the Tour of Lombardy.

Milan–San Remo and Tour of Lombardy Double

The Tour of Lombardy is one of five Monuments in cycling, one of two Italian Monuments together with Milan–San Remo. Milan–San Remo is called the Spring Classic and considered a sprinters race, whereas the Tour of Lombardy is called the Autumn Classic and considered a climbers race. In total, 21 riders have won both races at least once in their career. Following Paolo Bettini, the most recent one to do this was Vincenzo Nibali who won the Primavera in 2018 and the Tour of Lombardy in 2015 and 2017.

Winning Milan–San Remo and the Tour of Lombardy in the same year is considered as something of a "holy grail" in Italian cycling, dubbed by Italian press as La Doppietta (The Double).[16] Seven riders have achieved this feat, on ten occasions. Fausto Coppi did it three consecutive times, Eddy Merckx is the last rider as yet.

- 1921:

Costante Girardengo (ITA)

Costante Girardengo (ITA)

- 1930:

Michele Mara (ITA)

Michele Mara (ITA)

- 1931:

Alfredo Binda (ITA)

Alfredo Binda (ITA)

- 1939:

Gino Bartali (ITA)

Gino Bartali (ITA)

- 1940:

Gino Bartali (ITA)

Gino Bartali (ITA)

- 1946:

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

- 1948:

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

- 1949:

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

- 1951:

Louison Bobet (FRA)

Louison Bobet (FRA)

- 1971:

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

- 1972:

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

Tripletta

Even rarer is the combination of winning all three of Italy's great cycling races, Milan–San Remo, the Tour of Lombardy and the Giro d'Italia in one year. This Italian Treble happened twice:

- 1949:

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

Fausto Coppi (ITA)

- 1972:

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

Eddy Merckx (BEL)

References

^ "Giro di Lombardia 2012". cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 26 September 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "History of the Giro di Lombardia". gazzetta.it.

^ "Cycling Revealed Timeline". cyclingrevealed.com.

^ ab "Daily Peloton - Pro Cycling News". dailypeloton.com.

^ Gianni Pignata (9 November 1973). "Merckx, doping nel "Lombardia"" [Merckx, doping in "Lombardia"]. La Stampa (in Italian). Editrice La Stampa. p. 19. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

^ "sporza video: Roger De Vlaeminck klopt Eddy Merckx in de Ronde van Lombardije (1974)". sporza.

^ http://www.autobus.cyclingnews.com/results/archives/oct97/lombardy97.html

^ Cycling News. "Bettini's brother dies". Cyclingnews.com.

^ "Museo del Ghisallo". Museo del Ghisallo.

^ "Muro di Sormano returns to Tour of Lombardy route". Cycling News. Future Publishing Limited. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

^ Stephen Farrand. "New Giro di Lombardia route unveiled". Cyclingnews.com.

^ O'Shea, Sadhbh (4 October 2015). "Nibali wins Il Lombardia". Cyclingnews.com. Immediate Media Company. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

^ Wynn, Nigel (4 October 2015). "Watch: Vincenzo Nibali's amazing descending in Il Lombardia". Cycling Weekly. Time Inc. UK. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

^ "The Hardest Monument Classic » Irish Peloton". irishpeloton.com.

^ agoravox (ed.). "Vogliono cancellare la corsa ciclistica più antica del mondo" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 October 2014.

^ "19 marzo 1952 - Milano-Sanremo". museociclismo.it.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giro di Lombardia. |

Official website

Giro di Lombardia palmares at Cycling Archives

- 2013 Route