Stefan Dušan

| Stefan Dušan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and autocrat of the Serbs, Greeks, Bulgarians and Albanians | |||||

Detail of fresco in the Lesnovo monastery, c. 1350. | |||||

| King of all Serbian and Maritime Lands | |||||

| Tenure | 8 September 1331 – 16 April 1346 | ||||

| Predecessor | Stefan Dečanski | ||||

| Successor | Stefan Uroš V | ||||

| Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks | |||||

| Tenure | 16 April 1346 – 20 December 1355 | ||||

| Successor | Stefan Uroš V | ||||

| Born | c. 1308 | ||||

| Died | 20 December 1355 (aged 47) Devoll, Serbian Empire (now Albania) | ||||

| Burial | Monastery of the Holy Archangels; after 1927: St. Mark's Church | ||||

| Spouse | Helena of Bulgaria | ||||

| Issue | Stefan Uroš V | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nemanjić | ||||

| Father | Stefan Dečanski | ||||

| Mother | Theodora Smilets of Bulgaria | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy | ||||

Stefan Uroš IV Dušan (Serbian Cyrillic: Стефан Урош IV Душан, pronounced [stêfaːn ûroʃ tʃětʋr̩ːtiː dǔʃan] (![]() listen)), known as Dušan the Mighty (Serbian: Душан Силни / Dušan Silni; c. 1308 – 20 December 1355), was the King of Serbia from 8 September 1331 and Emperor and autocrat of the Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks and Albanians from 16 April 1346 until his death. Dušan conquered a large part of southeast Europe, becoming one of the most powerful monarchs of the era. Under Dušan's rule, Serbia was the major power in the Balkans, and a multi-lingual empire that stretched from the Danube in the north to the Gulf of Corynth in the south, with its capital in Skopje.[1] He enacted the constitution of the Serbian Empire, known as Dušan's Code, perhaps the most important literary work of medieval Serbia.

listen)), known as Dušan the Mighty (Serbian: Душан Силни / Dušan Silni; c. 1308 – 20 December 1355), was the King of Serbia from 8 September 1331 and Emperor and autocrat of the Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks and Albanians from 16 April 1346 until his death. Dušan conquered a large part of southeast Europe, becoming one of the most powerful monarchs of the era. Under Dušan's rule, Serbia was the major power in the Balkans, and a multi-lingual empire that stretched from the Danube in the north to the Gulf of Corynth in the south, with its capital in Skopje.[1] He enacted the constitution of the Serbian Empire, known as Dušan's Code, perhaps the most important literary work of medieval Serbia.

Dušan promoted the Serbian Church from an archbishopric to a Patriarchate, finished the construction of the Visoki Dečani monastery (a UNESCO site), and founded the Saint Archangels Monastery, among others. Under his rule Serbia reached its territorial, political, economic, and cultural peak.[2]

Dušan died in 1355, seen as the end of resistance against the advancing Ottoman Empire and the subsequent fall of the Eastern Orthodox Church in the region.[3]

Contents

1 Background

2 Biography

2.1 Youth and usurpation

2.2 Personal traits

2.3 Early reign

2.4 Imperial coronation and autocephaly of the Serbian church

2.5 Epirus and Thessaly

2.6 War with the Bosnian principality

2.7 Death

3 Religious activity

3.1 Church policy

4 Reign

4.1 Royal ideology

4.2 Lawmaker

4.3 Military tactics

5 Name, epithets and titles

6 Legacy

7 Family

8 Foundations

9 In fiction

10 See also

11 Notes

12 References

13 External links

Background

Fresco of Stefan Dečanski and Stefan Dušan, Visoki Dečani monastery, 14th century (UNESCO)

In 1314, Serbian King Stefan Milutin quarreled with his son, Stefan Dečanski. Milutin sent Dečanski to Constantinople to have him blinded, though he was never totally blinded.[4] Dečanski wrote to Danilo, the Bishop of Hum, asking him to intervene with his father.[5] Danilo wrote to Archbishop Nicodemus of Serbia, who spoke with Milutin and persuaded him to recall his son.[5] In 1320 Dečanski was permitted to return to Serbia and was given the appanage of 'Budimlje' (modern Berane),[5] while his half-brother, Stefan Konstantin, held the province of Zeta.[6]

Milutin became ill and died on 29 October 1321, and Konstantin was crowned king.[7] Civil war erupted immediately, as Dečanski and his cousin, Stefan Vladislav II, claimed the throne. Konstantin refused to submit to Dečanski, who then invaded Zeta, defeating and killing Konstantin.[7] Dečanski was crowned king on 6 January 1322 by Nicodemus, and his son, Stefan Dušan, was crowned “young king”.[6] Dečanski later granted Zeta to Dušan, indicating him as the intended heir.[7] In the meantime, Vladislav II mobilized local support from Rudnik, the former appanage of his father, Stefan Dragutin.[7] Vladislav proclaimed himself king, and he was supported by the Hungarians, consolidating control over his lands and preparing for battle with Dečanski.[7] As was the case with their fathers, Serbia was divided by the two independent rulers; in 1322 and 1323 Ragusan merchants freely visited both lands.[7]

In 1323, war broke out between Dečanski and Vladislav. Rudnik had fallen to Dečanski by the end of 1323, and Vladislav appeared to have fled north.[7] Vladislav was defeated in battle in late 1324 and fled to Hungary,[8] leaving the Serbian throne to Dečanski as undisputed "king of All Serbian and Maritime lands".

Biography

Youth and usurpation

Dušan was the eldest son of King Stefan Dečanski and Theodora Smilets, the daughter of emperor Smilets of Bulgaria. He was born circa 1308 in Serbia, but with the exile of his father in 1314, the family lived in Constantinople until 1320, when his father was allowed to return. In Constantinople he learned Greek, gained an understanding of Byzantine life and culture, and became acquainted with the Byzantine Empire. He was more a soldier than a diplomat; in his youth he fought exceptionally in two battles: in 1329 he defeated the Bosnian ban Stephen II Kotromanić, and in 1330 the Bulgarian emperor Michael III Shishman in the Battle of Velbužd. Dečanski appointed his nephew Ivan Stephen (through Anna Neda) to the throne of Bulgaria in August 1330.

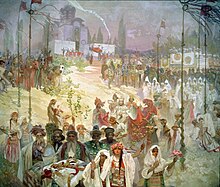

"Wedding of Emperor Dušan", by Paja Jovanović

Dečanski's decision not to attack the Byzantines after the victory at Velbazhd, when he had an opportunity, resulted in the alienation of many nobles,[9] who sought to expand to the south.[10] By January or February 1331, Dušan was quarreling with his father, perhaps pressured by the nobility.[10] According to contemporary pro-Dušan sources, advisors turned Dečanski against his son, and he decided to seize and exclude Dušan from his inheritance. Dečanski sent an army into Zeta against his son; the army ravaged Skadar (modern Shkodër), but Dušan had crossed the Bojana river. A brief period of anarchy took place in parts of Serbia before father and son concluded peace in April 1331.[9] Three months later, Dečanski ordered Dušan to meet him. Dušan feared for his life and his advisors persuaded him to resist, so Dušan marched from Skadar to Nerodimlje, where he besieged his father.[9] Dečanski fled, and Dušan captured the treasury and family. He then pursued his father, catching up with him at Petrić. On 21 August 1331 Dečanski surrendered, and on the advice or insistence of Dušan's advisors, he was imprisoned.[9] Dušan was crowned King of All Serbian and Maritime lands in the first week of September.[10]

The civil war had prevented Serbia from aiding Ivan Stephen and Anna Neda in Bulgaria, who were deposed in March 1331, taking refuge in the mountains. Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria feared Serbia, as the situation there had settled, and he immediately sought peace with Dušan.[10] As Dušan wanted to move against richer Byzantium, the two made peace and an alliance in December 1331, accepting Ivan Alexander as ruler. It was sealed with the marriage of Dušan and Helena of Bulgaria, Empress of Serbia, the sister of Ivan Alexander.[10]

Personal traits

Contemporary writers described Dušan as unusually tall and strong, "the tallest man of his time", very handsome, and a rare leader full of dynamism, quick intelligence, and strength,[11][12] bearing "a kingly presence".[13] According to the contemporary depictions, he had dark hair and brown eyes; in adult age he grew beard and longer hair.

Early reign

Main Gate of the Prizren Fortress in Prizren, Dušan's first capital

Serbia made some raids into the Macedonia region in late 1331, but a planned major attack on Byzantium was delayed as Dušan had to suppress revolts in Zeta in 1332.[14] Dušan's ingratitude toward those who had aided his rise — the Zetan nobility may have been neglected their promised reward and greater influence — may have been the cause of the rebellion, which was suppressed in the course of the same year.[14]

Dušan began to fight against the Byzantine Empire in 1334, and warfare continued with interruptions of various duration until his death in 1355. Twice he became involved in larger conflicts with the Hungarians, but these clashes were mostly defensive. Dušan's armies were initially defeated by Charles I of Hungary's 80,000-strong royal armies in Šumadija in 1336. As the Hungarians advanced south towards a hostile terrain, Dušan's cavalry launched sevaral attacks in the narrow open fields, resulting in a rout of Hungarian troops, which retreated to the north of Danube. Charles I was wounded by an arrow but survived. As a result, the Hungarians lost Mačva and Belgrade. Dušan then focused his attention on the internal affairs of his country, writing, in 1349, the first statute book of the Serbs.[15]

To the west, Dušan scored victories over Hungarian leader Louis the Great that gave him eastern half of modern Bosnia, and his coins were minted at Kotor.[16] Dušan was also successful against Louis' vassals: he defeated the armies of the Croatian ban and the forces of Hungarian voivodes. He was at peace with Ivan Alexander Bulgaria, who even helped him on several occasions, and he is said to have visited Ivan Alexander at his capital. Bulgaria became a Serbian vassal in 1331, a situation that lasted until 1365.[17]

Dušan exploited the civil war in the Byzantine Empire between the regent of the minor Emperor John V Palaiologos, Anna of Savoy, and his father's general John Kantakouzenos. Dušan and Ivan Alexander picked opposite sides in the conflict but remained at peace with each other, taking advantage of the Byzantine civil war to secure gains for themselves.

Dušan's systematic offensive began in 1342, and in the end he conquered all Byzantine territories in the western Balkans as far as Kavala, except for the Peloponnesus and Thessaloniki, which he could not besiege due to his small fleet. There has been speculation that Dušan's ultimate goal was no less than to conquer Constantinople and replace the declining Byzantine Empire with a united Orthodox Greco-Serbian Empire under his control.[18][19] In May 1344, his commander Preljub was stopped at Stephaniana by a Turkic force of 3,100.[20] The Turks won the battle, but the victory was not enough to thwart the Serbian conquest of Macedonia.[21][22] Faced with Dušan's aggression, the Byzantines sought allies in the Ottoman Turks, whom they brought into Europe for the first time. [23]

In 1343, Dušan added "of Romans (Greeks)" to his self-styled title "King of Serbia, Albania and the coast".[24] In 1345 he began calling himself tsar, equivalent of Emperor, as attested in charters to two athonite monasteries, one from November 1345 and the other from January 1346, and around Christmas 1345 at a council meeting in Serres, which was conquered on 25 September 1345, he proclaimed himself "Tsar of the Serbs and Romans" (Romans is equivalent to Greeks in Serbian documents).[24]

Imperial coronation and autocephaly of the Serbian church

The coronation of the Tsar Stefen Dušan in Skopje, part of the Slav Epic series by Alfons Mucha, 1926

Skopje Fortress, where Dušan adopted the title of Emperor at his coronation

On 16 April 1346 (Easter), Dušan convoked a huge assembly at Skopje, attended by the Serbian Archbishop Joanikije II, the Archbishop of Ochrid Nikolas I, the Bulgarian Patriarch Simeon, and various religious leaders of Mount Athos. The assembly and clerics agreed upon, and then ceremonially performed, the raising of the autocephalous Serbian Archbishopric to the status of Serbian Patriarchate.[24] The Archbishop from then on was titled Serbian Patriarch, although some documents called him Patriarch of Serbs and Greeks, with the seat at the Monastery of Peć.[24] The first Serbian Patriarch Joanikije II solemnly crowned Dušan as "Emperor and autocrat of Serbs and Romans" (Greek Bασιλεὺς καὶ αὐτoκράτωρ Σερβίας καὶ Pωμανίας).[24] Dušan had his son Uroš crowned King of Serbs and Greeks, giving him nominal rule over the Serbian lands, and although Dušan was governing the whole state, he had special responsibility for the Roman (Byzantine) lands.[25][24]

A further increase in the Byzantinization of the Serbian court followed, particularly in court ceremonial and titles.[24] As Emperor, Dušan could grant titles only possible as an Emperor.[26] In the years that followed, Dušan's half-brother Symeon Uroš and brother-in-law Jovan Asen became despotes. Jovan Oliver already had the despot title, granted to him by Andronikos III. His brother-in-law Dejan Dragaš and Branko Mladenović were granted the title of sebastocrator. The military commanders (voivodes) Preljub and Vojihna received the title of caesar.[26] The raising of the Serbian Patriarch resulted in the same spirit as bishoprics became metropolitans, as for example the Metropolitanate of Skopje.[26]

Serbian Patriarchate took over sovereignty on Mt. Athos and the Greek eparchies under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, while the Archbishopric of Ohrid remained autocephalous. For those acts he was excommunicated by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in 1350.[26]

Epirus and Thessaly

In 1347, Dušan conquered Epirus, Aetolia and Acarnania, appointing his half-brother, despot Simeon Uroš as governor of those provinces. In 1348, Dušan also conquered Thessaly, appointing Preljub as governor. In eastern regions of Macedonia, he appointed Vojihna as governor of Drama. Once Dušan conquered Byzantine possessions in western regions, he sought to obtain Constantinople.[27] To acquire the city, he needed a fleet.[27] Knowing that fleets of southern Serbian Dalmatian towns were not strong enough to overcome Constantinople, he opened negotiations with Venice, with which he maintained fairly good relations.[27] Venice feared a reduction of privileges in the Empire if Serbs became the masters of Constantinople over the weakened Byzantines. But if the Venetians had allied with Serbia, Dushan would have examined existing privileges. Once he became master of all Byzantine lands (especially Thessalonika and Constantinople) the Venetians would have gained privileges. But Venice chose to avoid a military alliance.[27] While Dušan sought Venetian aid against Byzantium, the Venetians sought Serbian support in the struggle against the Hungarians over Dalmatia. When sensing that Serbian aid would result in a Venetian obligation to Serbia, Venice politely turned down Dušan’s offers of help.[27]

While Dušan launched the Bosnian campaign (absent the Serbian troops in Macedonia and Thessaly), Kantakouzenos tried to regain lands Byzantium had lost.[28] In his support, the Constantinopolitan patriarch Kallistos excommunicated Dušan in order to discourage the Greek population in Dušan's Greek provinces from supporting the Serbian administration and thereby assist the Kantakouzenos campaign.[28] The excommunication did not stop Dušan's relations with Mount Athos, which still addressed him as Emperor, though rather as Emperor of Serbs than Emperor of Serbs and Greeks.[29]

Kantakouzenos raised a small army and took the Chalcidic peninsula, then Veria and Voden.[29] Veria was the richest town in the Bottiaea region. Dušan had earlier replaced many Greeks with Serbs, including a Serb garrison.[29] However, the remaining locals were able to open the gates for Kantakouzenos in 1350.[29] Voden resisted Kantakouzenos but was taken by assault.[29] Kantakouzenos then marched toward Thessaly but was stopped at Servia by Caesar Preljub and his army of 500 men.[29] The Byzantine force retired to Veria, and the aiding Turk contingent went off plundering, reaching Skopje.[29] Once news of the Byzantine campaign reached Dušan in Hum, he quickly reassembled his forces from Bosnia and Hum and marched for Thessaly.[29]

War with the Bosnian principality

Serbian Empire and neighbors at death of Tsar Dušan, 1355

Dušan evidently wanted to expand his rule over the provinces that had earlier been in the hands of Serbia, such as Hum, which was annexed by the Hungarian protégé and Bosnian Ban Stephen II Kotromanić in 1326.[27] In 1329, Ban Stephen II launched an attack on Lord Vitomir, who held Travunia and Konavle. The Bosnian army was defeated at Pribojska Banja by Dušan, when he was still Young King. The Ban soon took over Nevesinje and the rest of Bosnia. Petar Toljenović, the Lord of "seaside Hum" and a distant relative of Dušan, sparked a rebellion against the new ruler, but he was soon captured and died in prison.

In 1350, Dušan attacked Bosnia, seeking to regain the previously lost land of Hum and stop raids on his tributaries at Konavle.[27] Venice sought a settlement between the two but failed.[27] In October he invaded Hum, with an army said to be of 80,000 men, and successfully occupied part of the disputed territory.[27] According to Orbini, Dušan had secretly been in contact with various Bosnian nobles, offering them bribes for support.[28] Many nobles, chiefly of Hum, were ready to betray the Ban, such as the Nikolić family, which was kin to the Nemanjić dynasty.[28] The Bosnian Ban avoided any major confrontation and did not meet Dušan in battle; he instead retired to the mountains and made small hit-and-run actions.[28] Most of Bosnia's fortresses held out, but some nobles submitted to Dušan.[28] The Serbs ravaged much of the countryside. With one army they reached Duvno and Cetina; another reached Krka, on which lay Knin (modern Croatia); and another took Imotski and Novi, where they left garrisons and entered Hum.[28] From this position of strength, Dušan tried to negotiate peace with the Ban, sealing it by the marriage of Dušan's son Uroš with Stephen's daughter Elizabeth, who would receive Hum as her dowry - restoring it to Serbia.[28] The Ban was not willing to consider this proposal.[28]

Dušan may have also launched the campaign in order to aid his sister, Jelena, who married Mladen III Subic of Omis, Klis and Skradin, in 1347.[28] Mladen died from Black Death (bubonic plague) in 1348, and Jelena sought to maintain the rule of the cities for herself and her son.[28] She was challenged by Hungary and Venice, so the dispatch of Serbian troops to western Hum and Croatia may have been for her aid, as operations in this region were unlikely to help Dušan conquer Hum.[28] If Dušan had intended to aid Jelena, rising trouble in the East precluded this.[28]

Death

Sarcophagus of Stefan Dušan, kept at St. Mark's church, Belgrade

Dušan had grand intentions to hold Belgrade, Mačva and Hum, conquer Durrës, Phillipopolis, Adrianople, Thessalonica, and Constantinople, and to place himself at the head of a grand crusading army to drive the Muslim Turks from Europe. His premature death created a large power vacuum in the Balkans, that ultimately enabled Turkish invasion and Turkish rule until the early 20th century. While mounting a crusade against the Turks, he fell ill (possibly poisoned) and died of a fever at Devoll on 20 December 1355. He was buried in his foundation, the Monastery of the Holy Archangels near Prizren.

His empire slowly crumbled. His son and successor Stefan Uroš V could not keep the integrity of the Empire intact for long, as several feudal families immensely increased their power, though nominally acknowledging Uroš V as Emperor. Simeon Uroš, Dušan's half-brother, had proclaimed himself Emperor after the death of Dušan, ruling a large area of Thessaly and Epirus, which he had received from Dušan earlier.

Today Dušan's remains are in the Church of Saint Mark in Belgrade.[30] Dušan is the only monarch of the Nemanjić dynasty who has not been canonised as a saint.

Religious activity

Much like his ancestors, Emperor Dušan was very active in renovating churches and monasteries, and also for founding new ones. First, he cared for the monasteries in which his parents were buried. Both the Banjska monastery, built by King Milutin, where his mother was buried, and the monastery of Visoki Dečani, an endowment of his father, were generously looked after. The monastery was built for eight years and it is certain that the Emperor's role in the building process was huge. Between 1337 and 1339, the emperor became ill, and he gave his word that if he survived, he would build a church and monastery in Jerusalem. At the time, there was one Serbian monastery in Jerusalem, dedicated to Archangel Michael (believed to be founded by King Milutin), and a number of Serbian monks at the Sinai Peninsula.

His greatest endowment was the Saint Archangels Monastery, located near the town of Prizren, in which he was originally buried. Dušan gave many possessions to this monastery, including the forest of Prizren which was supposed to be a special property of the monastery where all precious goods and relics were to be stored.

His son, Stefan Uroš V, did not make peace with the Constantinopolitan Patriarch. The first initiave was made by despot Uglješa in 1368, which resulted that the areas under his rule were restored to Constantinople. The final initiative for reconciliation between the churches came from Prince Lazar in 1375. There is no evidence of an existing cult of Emperor Dušan in the decades after his death. Dušan's charter to Ragusa (Dubrovnik) served as a statute in the future trade between Serbia and Ragusa, and its regulations were deemed inviolable. Emperor Dušan's legacy was esteemed in Ragusa. Later folk tradition in Serbia included various attitudes toward Dušan, mostly negative, made under the influence of the church.

Church policy

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:left;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

Monastery of the Holy Archangels in Prizren

Treskavec Monastery near Prilep

With the raising of the Serbian Archbishopric to a Patriarchate, serious changes in the organization of the church followed. Joanikije II became Patriarch. Bishoprics (Eparchies) were raised to Metropolitanates, and new territories of the Ochrid Archbishopric and Ecumenical Constantinople were added to the jurisdiction of the Serbian church. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople had Dušan excommunicated in 1350, although this did not affect the religious organization.

Under Serbian jurisdiction came one of the foremost centers of spirituality - Mount Athos.[31] As of November 1345, Athonite monks accept his supreme rule, and Dušan guaranteed autonomy, also giving a row of economic privileges, with tremendous gifts and endowments. The monks of Chilandar (the cradle of the Serbian church, founded by Saint Sava, his ancestor) came at the front of the ecclesiastical community.

In his codex, Dušan accentuates his role as a protector of Christianity and points out the independence of the church. From the codex we can also see care that the parishes are equally arranged both in cities and villages. He was also taking care of few churches and monasteries from Bari to the west, to Jerusalem to the east.

Besides Orthodox Christians, there were many Catholics in the Empire, mostly in the coastal cities, Cattaro, Alessio (modern Lezhë)) etc. In the court of Dušan there were also Catholics (servants from Cattaro and Ragusa, mercenaries, guests etc.). In the central parts, Saxons were in areas active in mining and trading. Catholics had the full right of faith, except for converting non-Catholics.

There are no historical record that traders of catholic faith complained about discrimination based on religion. Dušan was also in contact with the Pope, he negotiated about formal acceptance of papal primacy, his two goals were: stopping Hungarian attacks in the north, and, with the help of the Pope, assemble and organize a crusade against the Turks (Muslims). The Pope sent an envoy led by Peter Tome to the Serbian court, however, according to Philippe de Mézières, their negotiations were followed by much unpleasantness, and the mission did not give the expected results.

Reign

Royal ideology

Some historians consider that the goal of Emperor Dušan was to establish a new, Serbian-Greek Empire, replacing the Byzantine Empire.[26]Ćirković considered his initial ideology as that of the previous Bulgarian emperors, who had envisioned co-rulership. However, starting in 1347, relations with John VI Kantakouzenos worsened, Dušan allied himself with rival John V Palaiologos.

Dušan was the first Serbian monarch who wrote most of his letters in Greek, also signing with the Imperial red ink. He was the first to publish prostagma, a kind of Byzantine document, characteristic for Byzantine rulers. In his royal title, Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, his claim as Eastern Roman (Byzantine) successor is clear. He also gave Byzantine court titles to his nobility,[24] something that would continue into the 16th century.

Lawmaker

Dušan's Code, the second oldest preserved constitution of Serbia

The most lasting monument to Dušan's rulership was a law code. For the purposes of Dušan's Code, a wealth of charters were published, and some great foreign works of law were translated to Serbian; however, the third section of the Code was new and distinctively Serbian, albeit with Byzantine influence and attention to a long legal tradition in Serbia. Dušan explained the purpose of his Code in one of in his charters; he intimated that its aims were spiritual and that the code would help his people to save themselves for the afterlife. The Code was proclaimed on 21 May 1349. in Skopje, and contained 155 clauses, while 66 further clauses were added at Serres in 1353 or 1354. The authors of the code are not known, but they were probably members of the court who specialised in law.

Dušan's Code proclaims on subjects both secular and ecclesiastic, the more so because Serbia had recently achieved full ecclesiastic autonomy as an independent Orthodox Church under a Patriarchate.[32] The first 38 clauses relate to the church and they deal with ussues that the Medieval Serbian Church faced, while the next 25 clauses relate to the nobility. Civil law is largely excluded, since it was covered in earlier documents, namely Saint Sava's Nomokamon and in Corpus Juris Civilis. Dušan's Code originally dealt with criminal law, with heavy emphasis on the concept of lawfulness, which was mostly taken directly from Byzantine law.

The original manuscript of Dušan's Code does not survive. The Code continued as a de facto constitution under the rule of Dušan's son, Stefan Uroš V, and after the fall of the Serbian Empire in 1371, it was used in all the successor provinces. It was officially used in the successor state, Serbian Despotate,[33] until its annexation by the Ottoman Empire in 1459. The Code was used as a reference for Serbian communities under Turkish rule, which exercised considerable legal autonomy in civil cases.[33] The Code was also used in the Serbian autonomical areas under the Republic of Venice, like Grbalj and Paštrovići.[34] It also served as the base of the Kanun of Albanian prince Leka Dukagjini (1410–1481), a set of customary laws in northern Albania that existed until the 20th century.[35]

Military tactics

Serbian military tactics consisted of wedge shaped heavy cavalry attacks with horse archers on the flanks. Many foreign mercenaries were in the Serbian army, mostly Germans as cavalry and Spaniards as infantry. He also had personal mercenary guards, mainly German knights. A German knight named Palman became the commander of the Serbian "Alemannic Guard" in 1331 upon crossing Serbia to Jerusalem; he became leader of all mercenaries in the Serbian Army. The main strength of the Serbian army was the armoured knight feared for their ferocious charge and fighting skills.

The Serbian expansion in the former territory of Byzantine Empire proceeded without a single major battle, it based on the blockade of Greek fortresses.[36]

Name, epithets and titles

Statue of Emperor Dušan in Belgrade

He was titled Young King as heir apparent on 6 January 1322 and was entitled the rule of Zeta; thus he ruled as "King of Zeta". In 1331 he succeeded his father as "King of all Serbian and Maritime Lands". In 1343 his title was "King of Serbia, Greeks, Albania and the coast". In 1345 he began calling himself tsar, Emperor, and in 1345 he proclaimed himself "Emperor of Serbs and Romans (Greeks)". On 16 April 1346 he was crowned Emperor of Serbs and Greeks. This title was soon enlarged into "Emperor and Autocrat of the Serbs and Greeks, the Bulgarians and Albanians".[3][37]

His epithet Silni (Силни) is translated into the Mighty,[38] but also the Great,[39]the Powerful[40] or the Strong.[41]

Legacy

Stefan Dušan was the most powerful Serbian ruler in the Middle Ages and remains a folk hero to Serbs. Dušan, a contemporary of England's Edward III, is regarded with the same reverence as the Bulgarians feel for Tsar Simeon, the Poles for Sigismund I the Old, and the Czechs for Charles IV. According to Steven Runciman, he was "perhaps the most powerful ruler in Europe" during the 14th century.[42] His state was a rival to the regional powers of Byzantium and Hungary, and it encompassed a large territory, which would also be his empire's greatest weakness. By nature a soldier and a conqueror, Dušan also proved to be very able but nonetheless feared ruler. His empire however, slowly crumbled at the hands of his son, as regional aristocrats distanced from the central rule.

The aim of restoring Serbia as an Empire it once was, was one of the greatest ideals of Serbs, living both in the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian lands. In 1526, Jovan Nenad, in the style of Dušan, proclaimed himself Emperor, when ruling a short-lived state of Serbian provinces under the crown of Hungary.

The Realm of the Slavs, written by Ragusian historian Mavro Orbin (l. ca. 1550-1614), saw Emperor Dušan's actions and works positively. The book served as the primary source about early history of South Slavs at the time and most of the western historians drew their information on the Slavs from it. Early Serbian historians, even though they wrote according to the sources, were influenced by the ideas of the time they lived in. They made efforts to harmonize with two different traditions: one from brevets[clarification needed] and public documents and other from genealogies and narrative writings. Of early historians, most information came from Jovan Rajić (1726–1801), who wrote fifty pages about Dušan's life. Rajić's work had great influence on Serbian culture of that time, and for decades it was the main source of information about Serbian history.

After the restoration of Serbia in the 19th century, continuity with the Serbian Middle Ages was accentuated, particularly of its greatest moment - during Emperor Dušan. A political agenda, as with a restoration of his Empire, would find its place in the political programmes of the Principality of Serbia, notably the Načertanije by Ilija Garašanin.

Family

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Stefan Dušan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fresco of Dušan, his wife Helena, and their son Uroš

By his wife, Helena of Bulgaria, Emperor Dušan had at least one child:

Stefan Uroš V, succeeded his father as Emperor, r. 1355-1371

According to contemporary Byzantine historian Nicephorus Gregoras, Dušan also had a daughter:

- Theodora

According to Gregoras, Dušan was negotiating a potential alliance with Orhan, which would have involved marrying off his daughter to Orhan himself or one of Orhan's sons in 1351. However, these negotiations broke down after the Serbian emissaries were attacked by Nikephoros Orsini - the marriage proposal was withdrawn and Serbia and the Ottoman Empire resumed hostilities.[43] Theodora most likely died between 1352-1354.

Some historians speculate that the couple had another child, a daughter. J. Fine suggested that it might be "Irene",[44] the wife of caesar Preljub (governor of Thessaly, d. 1355-1356), mother of Thomas Preljubović (Ruler of Epirus, 1367–1384). In one theory, she married Radoslav Hlapen, Governor of Voden and Veria and Lord of Kastoria, after her first husband's death in 1360. This hypothesis is not widely accepted.[45]

Foundations

- Saint Archangels Monastery

- Podlastva monastery

- Duljevo monastery

Reconstructions:

- Visoki Dečani

In fiction

- Epic folk song "Ženidba Cara Dušana" ("Emperor Dušan's wedding").

- 1875 historical three-tome novel "Car Dušan" ("Emperor Dušan") by Dr Vladan Đorđević.[46]

- 1987 historical novel "Stefan Dušan" by Slavomir Nastasijević.[47]

- 2002 historical novel "Dušan Silni" ("Dušan the Great") by Mile Kordić.[48]

See also

- Dušan's Code

- Serbian Empire

- Serbian Patriarchate of Peć

- Serbian Despotate

- Serbia in the Middle Ages

- Byzantine civil war of 1341–47

- Lesnovo monastery

Stefan Dušan Nemanjić dynasty Born: 1308 Died: 20 December 1355 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

New title | Emperor of Serbia 16 April 1346 – 20 December 1355 | Succeeded by Stefan Uroš V |

| Preceded by Stefan Uroš III | King of Serbia 8 September 1331 – 16 April 1346 | Succeeded by Stefan Uroš V |

| Royal titles | ||

| Preceded by Stefan Konstantin | Prince of Duklja 6 January 1322 – 8 September 1331 | Succeeded by Stefan Uroš V |

Notes

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

^ Positive Peace in Kosovo: A Dream Unfulfilled by Elisabeth Schleicher, page 49, 2012

^ Bury, John Bagnell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 517..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bury, John Bagnell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 517..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Hupchick 1995, p. 141

^ Fine 1994, p. 260,263

^ abc Fine 1994, p. 262.

^ ab Fine 1994, p. 263.

^ abcdefg Fine 1994, p. 264.

^ Fine 1994, p. 265.

^ abcd Fine 1994, p. 273.

^ abcde Fine 1994, p. 274.

^ Paul Pavlovich, The Serbians: the story of a people, p. 35

^ William Miller, The Balkans: Roumania, Bulgaria, Servia, and Montenegro, p. 273: "Character of Dušan"

^ Andrew Archibald Paton, Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic, Vol 1, p. 17

^ ab Fine 1994, p. 275.

^ Károly Szilágyi. "Hungarians and Serbs during the centuries". Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

^ Turkey in Europe by Charles Eliot, pag. 38

^ Churches of Eastern Cheristendom

^ Nicol (1993), p. 121: "The resulting assimilation of Byzantine culture by the Serbians helped to fortify the ideal of a Slavo-Byzantine Empire, which came to dominate the mind of Milutin's grandson, Stephen Dusan, later in the fourteenth century".

^ Radoman Stankovic, The Code of Serbian Emperor Stephan Dushan, Serbian Culture of the 14th Century. Volume I: "Powerful Byzantium started to decline, and young Serbian King Stephan Dushan, Stephan of Dechani's son, wanted, by getting crowned in 1331, to replace weakened Byzantium with the powerful Serbian-Greek Empire. [...] By proclaiming himself emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, Dushan showed that he aspired to a legitimate rule over the subjects of the Byzantine Empire".

^ Fine 1994, p. 303

^ Fine 1994, p. 304

^ Soulis 1984, p. 25

^ Vizantološki institut, Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, (Naučno delo, 1996), 194.

^ abcdefgh Fine 1994, p. 309.

^ Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 468.

^ abcde Fine 1994, p. 310.

^ abcdefghi Fine, p. 322

^ abcdefghijklm Fine, p. 323

^ abcdefgh Fine 1994, p. 324

^ Mitchell, Laurence (2010), Serbia, Bradt Travel Guides ed. 3. p. 149.

ISBN 1-84162-326-1

^ p. 66

^ http://againandagaininpeace.com/2012/02/07/the-serbian-church-in-history-the-serbian-patriarchate/[permanent dead link]

^ ab Sedlar, p. 330

^ Sindik, I. (1951) Dušanovo zakonodavstvo u Paštrovićima i Grblju. u: Zbornik u čast šeste stogodišnjice Zakonika cara Dušana, Beograd: Srpska akademija nauka, I, 119-182

^ Nikolaus Wilhelm-Stempin (2009), Das albanische Gewohnheitsrecht aus der Perspektive der rechtlichen Volkskunde, p. 5. GRIN Verlag,

ISBN 978-3-640-40128-4

^ Jean W Sedlar: East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500 - PAGE: 384, University of Washington Press

^ Clissold 1968, p. 98

^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 11, p. 234

^ Europa Publications; 4th 1999 (1999). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, 1999. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 944–. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

^ Vladislav Boskovic (14 December 2009). King Vukasin and the Disastrous Battle of Marica. GRIN Verlag. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-640-49243-5.

^ Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

^ Steven Runciman, Byzantine Civilization. Cited in Radoman Stanković, The Code of Serbian Emperor Stephan Dushan, Serbian Culture of the 14th Century. Volume I

^ George Ostrogorsky (1986), Byzantine sources on the history of the peoples of Yugoslavia, (Institute of Byzantine Studies), VI-280.

^ Profile of Stefan IV in Medieval Lands by Charles Cawley

^ Група аутора, "Родословне таблице и грбови српских династија и властеле (према таблицама Алексе Ивића)" (друго знатно допуњено и проширено издање), Београд, 1991.

ISBN 86-7685-007-0

^ Talija Izdavaštvo, accessed on 15-Apr-17, http://www.talijaizdavastvo.rs/korpa/knjige/34-dr-vladan-dordevic-trilogija-car-dusan.html

^ Delfi.rs, accessed on 15-Apr-17, http://www.delfi.rs/knjige/49995_stefan_dusan_knjiga_delfi_knjizare.html

^ Knjižare Vulkan, accessed on 16-Apr-17, https://www.knjizare-vulkan.rs/knjige/dusan-silni-mile-kordic-isbn-9788683583270

References

Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press.

Dennis P. Hupchick (1995). Conflict and chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-12116-7.

Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nicol, Donald M. (1996). The Reluctant Emperor: A Biography of John Cantacuzene, Byzantine Emperor and Monk, C. 1295-1383. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press.

Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331-1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection.

- Vizantološki institut, Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, (Naučno delo, 1996), 194.

A short history of Yugoslavia from early times to 1966, Stephen Clissold, Henry Clifford Darby, Stephen Clissold, CUP Archive, 1968

ISBN 0-521-09531-X

Alexander Soloviev "Selected Monuments of Serbian Law from the 12th to 15th centuries" (1926)

Alexander Soloviev "Legislation of Stefan Dušan, emperor of Serbs and Greeks" (1928)

Alexander Soloviev "Dušan's Code in 1349 and 1354" (1929)

Alexander Soloviev "Greek charters of Serbian rulers" Soloviev and Makin {1936}- Harris, Jonathan, The End of Byzantium. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010.

ISBN 978-0-300-11786-8

- Pirivatrić Srđan, Entering of Stefan Dušan into the Empire, Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta 2007, Issue 44, Pages: 381-409, doi:10.2298/ZRVI0744381P

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stefan Dušan. |

- Historical library:Stefan Dušan

Dušan Stefan Dušan at Encyclopædia Britannica