Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho | |

|---|---|

Camacho in 1943. | |

| 45th President of Mexico | |

In office 1 December 1940 (1940-12-01) – 30 November 1946 (1946-11-30) | |

| Preceded by | Lázaro Cárdenas |

| Succeeded by | Miguel Alemán Valdés |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1897-04-24)24 April 1897 Teziutlán, Puebla, Mexico |

| Died | 13 October 1955(1955-10-13) (aged 58) Estado de México, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Institutional Revolutionary Party |

| Spouse(s) | Soledad Orozco |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1914-1933 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

Manuel Ávila Camacho (Spanish pronunciation: [maˈnwel ˈaβila kaˈmatʃo]; 24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955) was a Mexican politician and military who served as the President of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Although he did participate in the Mexican Revolution and achieved a high rank, he came to the presidency of Mexico because of his direct connection to General Lázaro Cárdenas, as a right-hand man, serving as his Chief of his General Staff during the Mexican Revolution and afterwards.[1] He was called affectionately by Mexicans "The Gentleman President" (“El Presidente Caballero”).[2] As president, he pursued "national policies of unity, adjustment, and moderation."[3] His administration completed the transition from military to civilian leadership, ended confrontational anticlericalism, reversed the push for socialist education, and restored a working relationship with the U.S. during World War II.[4]

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Early career

3 Presidency

3.1 End of conflict between church and state

3.2 Domestic policy

3.3 Foreign policy

4 Later years and death

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Early life and education

Manuel Ávila was born in Teziutlán, a small but economically important town in Puebla, to middle-class parents, Manuel Ávila Castillo and Eufrosina Camacho Bello.[5] His older brother Maximino Ávila Camacho was a more dominant personality. There were several other siblings, among them a sister, María Jovita Ávila Camacho, and several brothers. Two of his brothers, Maximino Ávila Camacho and Rafael Ávila Camacho, served as governors of Puebla. Manuel Ávila Camacho did not receive a university degree, although he studied at the National Preparatory School.

Early career

He joined the revolutionary army in 1914 as a Second Lieutenant and reached the rank of colonel by 1920. The same year, he served as the Chief of Staff of the state of Michoacán under Lázaro Cárdenas and became his close friend. He opposed the 1923 rebellion of former revolutionary general Adolfo de la Huerta.[6] In 1929, he fought under General Cárdenas against the Escobar Rebellion, the last serious military rebellion of disgruntled revolutionary generals, and the same year, he achieved the rank of Brigadier General. He was married to Soledad Orozco García (1904-1996), who was born in Zapopan, Jalisco, and was a member of a prominent family in Jalisco.

After his military service, Ávila entered the public arena in 1933 as the executive officer of the Secretariat of National Defense and became Secretary of National Defense in 1937. In 1940, he was elected president of Mexico, after he had appointed to represent the party that later became the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

Camacho won the controversial presidential election over right-wing candidate and revolutionary-era General Juan Andreu Almazán.

Presidency

End of conflict between church and state

Institutional Revolutionary Party logo

Camacho was a professed Catholic and said, "I am a believer". Since the revolution, all presidents until 1940 had been anticlerical.[7] During Camacho's term, the conflict between the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico and the Mexican state largely ended.

Domestic policy

Mexican Social Security Institute logo

Domestically, he protected the working class, creating the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) in 1943. He worked to reduce illiteracy. He continued land reform and declared a rent freeze to benefit low-income citizens.

He promoted election reform and passed a new electoral law passed in 1946 that made it difficult for opposition parties of the far right and the far left to operate legally. The law established the following criteria that needed to be fulfilled by any political organization in order to be recognized as a political party:

- must have at least 10,000 active members in 10 states;

- must exist at least three years before elections;

- must agree with the principles established in the constitution;

- must not form alliances or be subordinated to international organizations or foreign political parties.[8]

On January 18, 1946, he had the Party of the Mexican Revolution (PRM) renamed to its current name, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The Mexican army had been a sector of the PRM; that sector was eliminated from the organization of the PRI.[9]

Economically, he pursued the country's industrialization, which benefited only a small group, and income inequality increased.[10]

World War II stimulated Mexican industry, which grew by approximately 10% annually between 1940 and 1945, and Mexican raw materials fueled the US war industry.[11] In agriculture, his administration invited the Rockefeller Foundation to introduction Green Revolution technology to bolster Mexico's agricultural productivity.[12]

In education, Camacho reversed Lázaro Cárdenas's policy of socialist education in Mexico and had the constitutional amendments that mandated it repealed.[13]

Foreign policy

Manuel Ávila Camacho, in Monterrey, having dinner with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

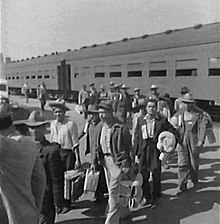

The first braceros arriving in Los Angeles, California by train in 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

Mexico provided military support for the Allies in World War II, with air Squadron 201

During his term, Camacho faced the difficulty of governing during World War II. After two of Mexico's ships (Potrero del Llano and Faja de Oro) carrying oil were destroyed by German submarines in the Gulf of Mexico,[14] Camacho declared war against the Axis powers on 22 May 1942. Mexican participation in World War II was mainly limited to an airborne squadron, the 201st (Escuadrón 201), to fight the Japanese in the Pacific. The squadron consisted of 300 men, and after receiving training in Texas, it was sent to the Philippines on 27 March 1945. On 7 June 1945, its missions started. By the end of the war, 5 Mexican soldiers had lost their lives in combat. However, with its short participation in the war, Mexico belonged to the victorious nations and had thus gained the right to participate in the postwar international conferences.[15]

Mexico's joining the conflict on the side of the Allies improved relations with the United States. Mexico provided both raw material for the conflict and also 300,000 guest workers under the Bracero program to replace some of the Americans who had left to fight in the war. Mexico also resumed diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, which had been broken off during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas.[citation needed] In 1945, Mexico signed the United Nations Charter and the following year, it became the headquarters of the Inter-American Conference about War and Peace.[citation needed]

Conflicts with the United States that had existed in the decades before his presidential term were resolved. Especially in the early years of World War II, Mexican-US relations were excellent. The United States provided Mexico with financial aid for improvements on the railway system and the construction of the Pan American Highway. Moreover, Mexican foreign debt was reduced.[16]

Later years and death

When his term ended in 1946, Camacho retired to work on his farm.[17]

See also

- List of heads of state of Mexico

References

^ Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: Harper Collins 1997, p. 494.

^ Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, chapter title, 491.

^ Howard F. Cline Mexico: Revolution to Evolution: 1940-1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1963, p. 153.

^ Roderic Ai Camp, "Manuel Avila Camacho" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 244. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

^ LaFrance, David G. "Manuel Ávila Camacho" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 116.

^ Camp, "Manuel Avila Camacho", p. 244.

^ Tuck, Jim. "Mexico's marxist guru: Vicente Lombardo Toledano (1894–1968)". Mexconnect. 9 October 2008.

^ Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2003). Historia de México II. Pearson Educación. p. 250..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Cline, Howard F. Mexico, 1940-1960: Revolution to Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press 1963, p. 153.

^ Beezley, William (2010). The Oxford History of Mexico. Oxford University Press. p. 501.

^ Beezley, William (2010). The Oxford History of Mexico. Oxford University Press. p. 500.

^ Cotter, Joseph. Troubled Harvest: Agronomy and Revolution in Mexico 1880-2002. Westport CT: Prager 2003.

^ Camp, "Manuel Avila Camacho," p. 244.

^ http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/1690.html. Retrieved 17 November 2013. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2003). Historia de México II. Pearson Educación. pp. 257–258.

^ Beezley, William (2010). The Oxford History of Mexico. Oxford University Press. p. 537.

^ Camp, "Manel Avila Camacho", p. 244.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manuel Ávila Camacho. |

Camp, Roderic Ai. Mexican Political Biographies. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona, 1982.

Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: Harper Collins 1997, chapter 17: "Manuel Ávila Camacho: The Gentleman President", pp. 491–525.- Medina, Luis. Historia de la Revolución Mexicana, periodo 1940-1952: Del cardenismo al avilacamachismo. Mexico City: Colegio de México 1978.

External links

Newspaper clippings about Manuel Ávila Camacho in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lázaro Cárdenas | President of Mexico 1940–1946 | Succeeded by Miguel Alemán Valdés |