Jeopardy!

| Jeopardy! | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Game show |

| Created by | Merv Griffin |

| Directed by | Bob Hultgren (1960s) Eleanor Tarshis (early 1970s) Jeff Goldstein (mid–1970s) Dick Schneider (1978–79, 1984–92) Kevin McCarthy (1992–2018) Clay Jacobsen (2018–present) |

| Presented by | Art Fleming (1964–75, 1978–79) Alex Trebek (1984–present) |

| Narrated by | Don Pardo (1964–75) John Harlan (1978–79) Johnny Gilbert (1984–present) |

| Theme music composer | Julann Griffin (1964–75) Merv Griffin (1978–79, 1984–present) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

No. of episodes | NBC (1964–75): 2,753[1] Syndication (1974–75): 39 NBC (1978–79): 108 Syndicated (1984–present): 7,000 (as of May 20, 2015)[2] |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) | Robert Rubin (1970s) Merv Griffin (1984–2000) Harry Friedman (1999–present) |

| Producer(s) | see below |

| Running time | approx. 22–26 minutes |

| Production company(s) | Merv Griffin Productions (1964–75, 1978–79) Merv Griffin Enterprises (1984–94) Columbia TriStar Television (1994–2001) Columbia TriStar Domestic Television (2001–2002) Sony Pictures Television (2002–present) Jeopardy Productions, Inc. |

| Distributor | Metromedia (1974–75) King World Productions (1984–2007) CBS Television Distribution (2007–present; US only) |

| Release | |

| Original network | NBC (1964–75, 1978–79) Syndicated (1974–75, 1984–present) |

| Picture format | 480i (SDTV) (1975–2006) 1080i (HDTV; downgraded to 720p locally in some markets) (2006–present) |

| Audio format | Stereo |

| Original release | NBC Daytime: March 30, 1964 (1964-03-30)[3] – January 3, 1975 (1975-01-03) Weekly syndication: September 1974 (1974-09) – September 1975 (1975-09) NBC Daytime: October 2, 1978 (1978-10-02) – March 2, 1979 (1979-03-02) Daily syndication: September 10, 1984 (1984-09-10) – present |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | Jep! Rock & Roll Jeopardy! Sports Jeopardy! |

| External links | |

| Website | |

Jeopardy! is an American television game show created by Merv Griffin. The show features a quiz competition in which contestants are presented with general knowledge clues in the form of answers, and must phrase their responses in the form of questions. The original daytime version debuted on NBC on March 30, 1964, and aired until January 3, 1975. A weekly nighttime syndicated edition aired from September 1974 to September 1975, and a revival, The All-New Jeopardy!, ran on NBC from October 1978 to March 1979. The current version, a daily syndicated show produced by Sony Pictures Television, premiered on September 10, 1984.

Both NBC versions and the weekly syndicated version were hosted by Art Fleming. Don Pardo served as announcer until 1975, and John Harlan announced for the 1978–1979 show. Since its inception, the daily syndicated version has featured Alex Trebek as host and Johnny Gilbert as announcer.

With over 7,000 episodes aired,[2] the daily syndicated version of Jeopardy! has won a record 33 Daytime Emmy Awards as well as a Peabody Award. In 2013, the program was ranked No. 45 on TV Guide's list of the 60 greatest shows in American television history. Jeopardy! has also gained a worldwide following with regional adaptations in many other countries. The daily syndicated series' 35th season premiered on September 10, 2018.[4]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 Gameplay

1.1 First two rounds

1.2 Final Jeopardy!

1.3 Winnings

1.4 Returning champions

1.5 Variations for tournament play

2 Conception and development

3 Personnel

3.1 Hosts and announcers

3.2 Clue Crew

3.3 Production staff

4 Production

4.1 Set

4.2 Theme music

4.3 Audition process

5 Broadcast history

5.1 Archived episodes

6 Reception

7 Tournaments and other events

7.1 Regular events

7.2 Special events

8 Record holders

9 Other media

9.1 Portrayals and parodies

9.2 Merchandise

9.3 Internet

10 References

10.1 Bibliography

11 External links

Gameplay

Three contestants each take their place behind a lectern, with the returning champion occupying the leftmost lectern (from the viewer's perspective). The contestants compete in a quiz game comprising three rounds: Jeopardy!, Double Jeopardy!, and Final Jeopardy!.[5] The material for the clues covers a wide variety of topics, including history and current events, the sciences, the arts, popular culture, literature, and languages.[6] Category titles often feature puns, wordplay, or shared themes, and the host will regularly remind contestants of topics or place emphasis on category themes before the start of the round.

First two rounds

The layout of the Jeopardy! game board since November 26, 2001, showing the dollar values used in the first round

The Jeopardy! and Double Jeopardy! rounds each feature six categories, each of which contains five clues, which are ostensibly valued by difficulty.[5] The dollar values of the clues increased over time. On the original Jeopardy! series, clue values in the first round ranged from $10 to $50.[7] On The All-New Jeopardy!, they ranged from $25 to $125. The current series' first round originally ranged from $100 to $500,[5] and were doubled to $200 to $1,000 on November 26, 2001.[8] On the Super Jeopardy! specials, clues were valued in points rather than in dollars, and ranged in the first round from 200 to 1,000 points.

The Jeopardy! round begins when the returning champion selects any position on the game board. The underlying clue is revealed and read aloud by the host, after which any contestant may ring in using a hand-held signaling device. The first contestant to ring in successfully is prompted to provide a response to the clue, phrased in the form of a question.[5] For example, if a contestant were to select "Presidents for $200", the resulting clue could be "This 'Father of Our Country' didn't really chop down a cherry tree", to which the correct response would be "Who is/was George Washington?" (Contestants are free to phrase the response in the form of any question; the traditional phrasing of "who is/are" for people or "what is/are" for things or words is almost always used.) If the contestant responds correctly, the clue's dollar value is added to the contestant's score, and they may select a new clue from the board. An incorrect response, or a failure to respond within five seconds, deducts the clue's value from the contestant's score and allows the other contestants the opportunity to ring in and respond.[5] If no contestant both rings in and responds correctly, the host gives the correct response; the "last correct questioner" chooses the next clue.[9]

Contestants are encouraged to select the clues in order from lowest to highest value, as the show's writers write the clues in each category to flow from one to the next, as is the case with game shows that ask questions in a linear string. Contestants are not required to do so unless the category requires clues to be taken in order; the "Forrest Bounce", a strategy in which contestants randomly pick clues to confuse opponents, has been used successfully by Arthur Chu and the strategy's namesake Chuck Forrest, despite Trebek noting that the strategy not only annoys him but staffers as well, since it also disrupts the rhythm that develops when revealing the clues and increases the potential for error.[10]

From the premiere of the original Jeopardy! until the end of the first season of the current syndicated series, contestants were allowed to ring in as soon as the clue was revealed. Since September 1985, contestants are required to wait until the clue is read before ringing in. To accommodate the rule change, lights were added to the game board (unseen by home viewers) to signify when it is permissible for contestants to signal;[11] attempting to signal before the light goes on locks the contestant out for half of a second.[12] The change was made to allow the home audience to play along with the show more easily and to keep an extremely fast contestant from potentially dominating the game. In pre-1985 episodes, a buzzer would sound when a contestant signaled; according to Trebek, the buzzer was eliminated because it was "distracting to the viewers" and sometimes presented a problem when contestants rang in while Trebek was still reading the clue.[11] Contestants who are visually impaired or blind are given a card with the category names printed in Braille before each round begins, and an audible tone is played after the clue has been read aloud.

The second round, Double Jeopardy!, features six new categories of clues. Clue values are doubled from the Jeopardy! round[5] (except in Super Jeopardy!, where Double Jeopardy! values ranged from 500 to 2,500 points). The contestant with the least amount of money at the end of the Jeopardy! round makes the first selection in Double Jeopardy!;[9] if there is a tie, the tied contestant standing at the leftmost lectern selects first.

A "Daily Double" is hidden behind one clue in the Jeopardy! round, and two in Double Jeopardy![5] The name and inspiration were taken from a horse racing term.[13] Only the contestant who uncovers a Daily Double may respond to that clue and need not use his/her signaling device to do so. Before the clue is revealed, the contestant must declare a wager, from a minimum of $5 to a maximum of his/her entire score (known as a "true Daily Double") or the highest clue value available in the round, whichever is greater.[9][14] A correct response adds the value of the wager to the contestant's score, while an incorrect response deducts it. Whether or not the contestant responds correctly, he or she chooses the next clue.[9]

During the Jeopardy! round, except in response to the Daily Double clue, contestants are not penalized for forgetting to phrase their response in the form of a question, although the host will remind contestants to watch their phrasing in future responses. In the Double Jeopardy! round and in the Daily Double in the Jeopardy! round, the phrasing rule is followed more strictly, with a response not phrased in the form of a question counting as wrong if it is not re-phrased before the host or judges make a ruling.[14] If it is determined that a previous response was wrongly ruled to be correct or incorrect, the scores are adjusted at the first available opportunity. If, after a game is over, a ruling change is made that would have significantly altered the outcome of the game, the affected contestant(s) are invited back to compete on a future show.[15]

Contestants who finish Double Jeopardy! with $0 or a negative score are automatically eliminated from the game at that point and awarded the third place prize. On at least one episode hosted by Art Fleming, all three contestants finished Double Jeopardy! with $0 or less, and as a result, no Final Jeopardy! round was played.[16] This rule is still in place for the Trebek version, although staff has suggested that it is not set in stone and that executive producer Harry Friedman may decide to display the clue for home viewers' play if such a situation were ever to occur.[17] During Celebrity Jeopardy! games, contestants with a $0 or negative score are given $1,000 for the Final Jeopardy! round.

Final Jeopardy!

The Final Jeopardy! round features a single clue. At the end of the Double Jeopardy! round, the host announces the Final Jeopardy! category, and a commercial break follows. During the break, barriers are placed between the contestant lecterns, and each contestant makes a final wager between $0 and his/her entire score. Contestants write their wagers using a light pen on an electronic display on their lectern.[18] After the break, the Final Jeopardy! clue is revealed and read by the host. The contestants have 30 seconds to write their responses on the electronic display, while the show's iconic "Think!" music plays in the background. In the event that either the display or the pen malfunctions, contestants can use an index card and a marker to manually write their response and wager. Visually impaired or blind contestants use a Braille keyboard to type in a wager and response.

Contestants' responses are revealed in order of their pre-Final Jeopardy! scores from lowest to highest. A correct response adds the amount of the contestant's wager to his/her score, while a miss, failure to respond, or failure to phrase the response as a question (even if correct) deducts it.[9] The contestant with the highest score at the end of the round is that day's winner. If there is a tie for second place, consolation prizes are awarded based on the scores going into the Final Jeopardy! round. If all three contestants finish with $0, no one returns as champion for the next show, and based on scores going into the Final Jeopardy! round, the two contestants who were first and second will receive the second-place prize, and the contestant in third will receive the third-place prize.

The strategy for wagering in Final Jeopardy! has been studied. If the leader's score is more than twice the second place contestant's score, the leader can guarantee victory by making a sufficiently small wager.[19]:269 Otherwise, according to Jeopardy! College Champion Keith Williams, the leader will usually wager such that he or she will have a dollar more than twice the second place contestant's score, guaranteeing a win with a correct response.[20] Writing about Jeopardy! wagering in the 1990s, Gilbert and Hatcher said that "most players wager aggressively".[19]:269

Winnings

The top scorer(s) in each game retain the value of their winnings in cash, and return to play in the next match.[5] Non-winners receive consolation prizes. Since May 16, 2002, consolation prizes have been $2,000 for the second-place contestant(s) and $1,000 for the third-place contestant.[21] Since the show does not generally provide airfare or lodging for contestants, cash consolation prizes alleviate contestants' financial burden. An exception is provided for returning champions who must make several flights to Los Angeles.[22]

Before 1984, all three contestants received their winnings in cash (contestants who finished with $0 or a negative score received consolation prizes). This was changed in order to make the game more competitive, and avoid the problem of contestants who would stop participating in the game, or avoid wagering in Final Jeopardy!, rather than risk losing the money they had already won.[23] From 1984 to 2002, non-winning contestants on the Trebek version received vacation packages and merchandise, which were donated by manufacturers as promotional consideration. As of 2004[update], the cash consolation prize is provided by Geico.[24]

Returning champions

The winner of each episode returns to compete against two new contestants on the next episode. Originally, a contestant who won five consecutive days retired undefeated and was guaranteed a spot in the Tournament of Champions; the five-day limit was eliminated at the beginning of season 20 on September 8, 2003.[25]

Since November 2014,[26] ties for first place following Final Jeopardy! are broken with a tie-breaker clue, resulting in only a single champion being named, keeping their winnings, and returning to compete in the next show. The tied contestants are given the single clue, and the contestant must give the correct question. A contestant cannot win by default if the opponent gives an incorrect question. That contestant must give a correct question to win the game. If neither player gives the correct question, another clue is given.[27] Previously, if two or all three contestants tied for first place, they were declared "co-champions", and each retained his or her winnings and (unless one was a five-time champion who retired prior to 2003) returned on the following episode. A tie occurred on the January 29, 2014, episode when Arthur Chu, leading at the end of Double Jeopardy!, wagered to tie challenger Carolyn Collins rather than winning; Chu followed Jeopardy! College Champion Keith Williams's advice to wager for the tie to increase the leader's chances of winning.[28][29] A three-way tie for first place has only occurred once on the Trebek version, on March 16, 2007, when Scott Weiss, Jamey Kirby, and Anders Martinson all ended the game with $16,000.[30] Until March 1, 2018,[26][31] no regular game had ended in a tie-breaker; numerous tournament games have ended with a tie-breaker clue.

If no contestant finishes Final Jeopardy! with a positive total, there is no winner. This has happened on several episodes,[32][33] most recently on January 18, 2016.[34] Three new contestants appear on the next episode. A triple zero has also occurred twice in tournament play (1991 Seniors and 2013 Teen), and also once in a Celebrity Week episode in 1998.[35] All consolation prize money (regular play, with one $2,000 and two $1,000 prizes, and Celebrity play, prize money for charities) are based on standard rules (score after Double Jeopardy!). In tournament play, an additional high scoring non-winner will advance to the next round (but all three players with a zero score in that game are eligible for that position should the score for that non-winner be zero; all tie-breaker rules apply).

A winner unable to return as champion because of a change in personal circumstances – for example, illness or a job offer – may be allowed to appear as a co-champion in a later episode.[36][37][38]

Typically, the two challengers participate in a backstage draw to determine lectern positions. In all situations with three new contestants (most notably tournaments in the first round), the draw will also determine who will take the champion's position and select first to start the game. (The player scoring the highest in the preceding round will be given the chance to select first in the semifinal and finals.)

Variations for tournament play

Tournaments generally run for 10 consecutive episodes and feature 15 contestants. The first five episodes, the quarter-finals, feature three new contestants each day. The winners of these five games, and the four highest scoring non-winners ("wild cards"), advance to the semi-finals, which run for three days. The winners of these three games advance to play in a two-game final match, in which the scores from both games are combined to determine the overall standings. This format has been used since the first Tournament of Champions in 1985 and was devised by Trebek himself.[39]

To prevent later contestants from playing to beat the earlier wild card scores instead of playing to win, contestants are "completely isolated from the studio until it is their time to compete".[40]

If there is a tie for the final wild card position, the non-winner that advances will be based on the same regulations as two contestants who tie for second; the tie-breaker is the contestant's score after the Double Jeopardy! round, and if further tied, the score after the Jeopardy! round determines the contestant who advances as the wild card.

If two or more contestants tie for the highest score (greater than zero) at the end of match (first round, semi-final game, or end of a two-game final), the standard tiebreaker is used. However, if two or more contestants tie for the highest score at the end of the first game of a two-game final, no tiebreaker is played.

If none of the contestants in a quarter-final or semi-final game end with a positive score, no contestant automatically qualifies from that game, and an additional wild card contestant advances instead.[41] This occurred in the quarter-finals of the 1991 Seniors Tournament and the semi-finals of the 2013 Teen Tournament.[41]

In the finals, contestants who finish Double Jeopardy! with a $0 or negative score on either day do not play Final Jeopardy! that day; their score for that leg is recorded as $0.

Conception and development

In a 1964 Associated Press profile released shortly before the original Jeopardy! series premiered, Merv Griffin offered the following account of how he created the quiz show:

| “ | My wife Julann just came up with the idea one day when we were in a plane bringing us back to New York City from Duluth. I was mulling over game show ideas, when she noted that there had not been a successful 'question and answer' game on the air since the quiz show scandals. Why not do a switch, and give the answers to the contestant and let them come up with the question? She fired a couple of answers to me: "5,280"—and the question of course was 'How many feet in a mile?'. Another was '79 Wistful Vista'; that was Fibber and Mollie McGee's address. I loved the idea, went straight to NBC with the idea, and they bought it without even looking at a pilot show.[42][43] | ” |

Griffin's first conception of the game used a board comprising ten categories with ten clues each, but after finding that this board could not easily be shown on camera, he reduced it to two rounds of thirty clues each, with five clues in each of six categories.[44] He originally intended the show to require grammatically correct phrasing (e.g., only accepting "Who is ..." for a person), but after finding that grammatical correction slowed the game down, he decided that the show should instead accept any correct response that was in question form.[45] Griffin discarded his initial title for the show, What's the Question?, when skeptical network executive Ed Vane rejected his original concept of the game, claiming, "It doesn't have enough jeopardies."[44][46]

Jeopardy! was not the first game show to give contestants the answers and require the questions. That format had previously been used by the Gil Fates-hosted program CBS Television Quiz, which aired from July 1941 until May 1942.[47]

Personnel

Hosts and announcers

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:left;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

The first three versions of the show were hosted by Art Fleming. Don Pardo served as announcer for the original NBC version and weekly syndicated version,[7] but when NBC's revival The All-New Jeopardy! launched in 1978, Pardo's announcing duties were taken over by John Harlan.[48]

Alex Trebek has served as host of the daily syndicated version since it premiered in 1984,[49] except when he switched places with Wheel of Fortune host Pat Sajak as an April Fool's joke on the episode aired April 1, 1997.[50] His most recent contract renewal, from May 2017, takes his tenure through the 2019–2020 season.[51] In the daily syndicated version's first pilot, from 1983, Jay Stewart served as the show's announcer, but Johnny Gilbert took over the role when that version was picked up as a series and has held it since then.[49]

Trebek will be 80 at the time his contract with Jeopardy! expires in 2020. On a Fox News program, he said the odds of retirement in 2020 were 50/50 "and a little less". He added that he might continue if he's "not making too many mistakes" but would make an "intelligent decision" as to when he should give up the emcee role.[52] In November 2018, it was announced that he had renewed his contract as host through 2022,[53] stating in January 2019 that the show's work schedule, consisting of 46 taping sessions each year, was still manageable for a man of his age.[54] On March 6, 2019, Trebek announced he had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. In a prepared video statement announcing his diagnosis, Trebek noted that his prognosis was poor but that he would aggressively fight the cancer in hopes of beating the odds and would continue hosting Jeopardy! for as long as he was able, joking that his contract obligated him to do so for three more years regardless of health.[55]

Clue Crew

Kelly Miyahara of the Clue Crew at the International CES in Winchester, Nevada

The Jeopardy! Clue Crew, introduced on September 24, 2001, is a team of roving correspondents who appear in videos, recorded around the world, to narrate some clues.[56] Explaining why the Clue Crew was added to the show, executive producer Harry Friedman said, "TV is a visual medium, and the more visual we can make our clues, the more we think it will enhance the experience for the viewer."[57]

Following the initial announcement of auditions for the team, over 5,000 people applied for Clue Crew posts.[57] The original Clue Crew members were Cheryl Farrell, Jimmy McGuire, Sofia Lidskog, and Sarah Whitcomb.[56] Lidskog departed the Clue Crew in 2004 to become an anchor on the high school news program Channel One News, and a search was held to replace her in early 2005.[58] The winners were Jon Cannon and Kelly Miyahara, who formally joined the crew starting in season 22, which premiered on September 12, 2005.[59] Farrell continued to record clues for episodes aired as late as October 2008,[60] and Cannon continued to appear until July 2009.[61]

The Clue Crew has traveled to 280 cities worldwide, spanning all 50 of the United States and 44 other countries. In addition to appearing in Jeopardy! clue videos, the team's members also travel to meet fans of the show and future contestants. Occasionally, they visit schools to showcase the educational game Classroom Jeopardy![62] Miyahara also serves as announcer for the Sports Jeopardy! spin-off series.[63]

Production staff

Robert Rubin served as the producer of the original Jeopardy! series for most of its run, and later became its executive producer.[64] Following Rubin's promotion, the line producer was Lynette Williams.[64]

Griffin was the daily syndicated version's executive producer until his retirement in 2000.[65] Trebek served as producer as well as host until 1987, when he began hosting NBC's Classic Concentration for the next four years.[65] At that time, he handed producer duties to George Vosburgh, who had formerly produced The All-New Jeopardy!. In the 1997–1998 season, Vosburgh was succeeded as producer by Harry Friedman, Lisa Finneran, and Rocky Schmidt. Beginning in 1999, Friedman became executive producer,[66] and Gary Johnson became the show's new third producer. In the 2006–2007 season, Deb Dittmann and Brett Schneider became the producers, and Finneran, Schmidt, and Johnson were promoted to supervising producers.[64]

The original Jeopardy! series was directed at different times by Bob Hultgren, Eleanor Tarshis, and Jeff Goldstein.[64] Dick Schneider, who directed episodes of The All-New Jeopardy!, returned as director for the Trebek version's first eight seasons. From 1992 to 2018, the show was directed by Kevin McCarthy, who had previously served as associate director under Schneider.[65] McCarthy announced his retirement after 26 years on June 26, 2018, and was succeeded as director by Clay Jacobsen.[67]

The current version of Jeopardy! employs nine writers and five researchers to create and assemble the categories and clues.[68] Billy Wisse and Michele Loud, both longtime staff members, are the editorial producer and editorial supervisor, respectively.[69] Previous writing and editorial supervisors have included Jules Minton, Terrence McDonnell, Harry Eisenberg, and Gary Johnson.[64]

The show's production designer is Naomi Slodki.[69] Previous art directors have included Henry Lickel, Dennis Roof,[70] Bob Rang,[64] and Ed Flesh (who also designed sets for other game shows such as The $25,000 Pyramid, Name That Tune, and Wheel of Fortune).[71]

Production

The daily syndicated version of Jeopardy! is produced by Sony Pictures Television (previously known as Columbia TriStar Television, the successor company to original producer Merv Griffin Enterprises).[72] The copyright holder is Jeopardy Productions, which, like SPT, operates as a subsidiary of Sony Pictures Entertainment.[73] The rights to distribute the program worldwide are owned by CBS Television Distribution, which absorbed original distributor King World Productions in 2007.[74]

The original Jeopardy! series was taped in Studio 6A at NBC Studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City,[75] and The All-New Jeopardy! was taped in Studio 3 at NBC's Burbank Studios at 3000 West Alameda Avenue in Burbank, California.[3] The Trebek version was initially taped at Metromedia Stage 7, KTTV, on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood,[3] but moved its production facilities to Hollywood Center Studios' Stage 9 in 1985. After the final shows of season 10 were recorded on February 15, 1994, the Jeopardy! production facilities were moved to Sony Pictures Studios' Stage 10 on Washington Boulevard in Culver City, California,[3] where the show has been recorded ever since.

Five episodes are taped each day, with two days of taping every other week.[76]

Set

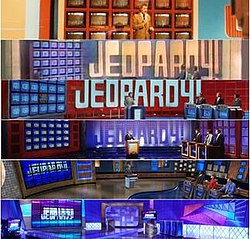

Various sets used by the syndicated version over the years. From top to bottom: 1984–85, 1985–91, 1991–96, 1996–2002, 2002–09, and 2009–13.

Various technological and aesthetic changes have been made to the Jeopardy! set over the years. The original game board was exposed from behind a curtain and featured clues printed on cardboard pull cards which were revealed as contestants selected them.[7]The All-New Jeopardy!'s game board was exposed from behind double-slide panels and featured flipping panels with the dollar amount on one side and the clue on the other. When the Trebek version premiered in 1984, the game board used individual television monitors for each clue within categories. The original monitors were replaced with larger and sleeker ones in 1991.[77] In 2006, these monitors were discarded in favor of a nearly seamless projection video wall,[78] which was replaced in 2009 with 36 high-definition flat-panel monitors manufactured by Sony Electronics.[79]

From 1985 to 1997, the sets were designed to have a background color of blue for the Jeopardy! round and red for the Double Jeopardy! and Final Jeopardy! rounds. At the beginning of season 8 in 1991, a brand new set was introduced that resembled a grid.[77] On the episode aired November 11, 1996, two months after the start of season 13, Jeopardy! introduced the first of several sets designed by Naomi Slodki, who intended the set to resemble "the foyer of a very contemporary library, with wood and sandblasted glass and blue granite".[80]

Shortly after the start of season 19 in 2002, the show switched to yet another new set,[81] which was given slight modifications when Jeopardy! and sister show Wheel of Fortune transitioned to high-definition broadcasting in 2006.[78] During this time, the show began to feature virtual tours of the set on its official web site.[82] The various HD improvements for Jeopardy! and Wheel represented a combined investment of approximately $4 million, 5,000 hours of labor, and 6 miles (9.7 km) of cable.[78] Both shows had been shot using HD cameras for several years before beginning to broadcast in HD. On standard-definition television broadcasts, the shows continue to be displayed with an aspect ratio of 4:3.

In 2009, Jeopardy! updated its set once again. The new set debuted with special episodes taped at the 42nd annual International CES technology trade show, hosted at the Las Vegas Convention Center in Winchester (Las Vegas Valley), Nevada, and became the primary set for Jeopardy! when the show began taping its 26th season, which premiered on September 14, 2009.[79] It was significantly remodeled when season 30 premiered in September 2013.[83]

Theme music

Since the debut of Jeopardy! in 1964, several different songs and arrangements have served as the theme music for the show, most of which were composed by Griffin. The main theme for the original Jeopardy! series was "Take Ten",[84] composed by Griffin's wife Julann.[85]The All-New Jeopardy! opened with "January, February, March" and closed with "Frisco Disco", both of which were composed by Griffin himself.[86]

The best-known theme song on Jeopardy! is "Think!", originally composed by Griffin under the title "A Time for Tony", as a lullaby for his son.[87] "Think!" has always been used for the 30-second period in Final Jeopardy! when the contestants write down their responses, and since the syndicated version debuted in 1984, a rendition of that tune has been used as the main theme song.[88] "Think!" has become so popular that it has been used in many different contexts, from sporting events to weddings.[89] Griffin estimated that the use of "Think!" had earned him royalties of over $70 million throughout his lifetime.[90] "Think!" led Griffin to win the Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) President's Award in 2003,[91] and during GSN's 2009 Game Show Awards special, it was named "Best Game Show Theme Song".[92] In 1997, the main theme and Final Jeopardy! recordings of "Think!" were rearranged by Steve Kaplan, who served as the show's music director until his December 2003 death.[93] In 2008, Chris Bell Music and Sound Design overhauled the Jeopardy! music package for the show's 25th anniversary.[94]

Audition process

Prospective contestants of the original Jeopardy! series called the show's office in New York to arrange an appointment and to preliminarily determine eligibility. They were briefed and auditioned together in groups of ten to thirty individuals, participating in both a written test and mock games. Individuals who were successful at the audition were invited to appear on the program within approximately six weeks.[95]

Auditioning for the current version of the show begins with a written exam, comprising fifty questions in total. This exam is administered online periodically, as well as being offered at regional contestant search events. Since season 15 (1998–99), the show has used a Winnebago recreational vehicle called the "Jeopardy! Brain Bus" to conduct regional events throughout the United States and Canada.[96] Participants who correctly answer at least 35 out of 50 questions advance in the audition process and are invited to attend in-person group auditions throughout the country. At these auditions, a second written exam is administered, followed by a mock game and interviews. Those who are approved are notified at a later time and invited to appear on the show. Those who have never been on the show, and have not been to an in-person audition in at least 18 months, are eligible to apply and take the online test.[97]

Broadcast history

The original Jeopardy! series premiered on NBC on March 30, 1964,[3] and by the end of the 1960s was the second-highest-rated daytime game show, behind only The Hollywood Squares.[98] The show was successful until 1974, when Lin Bolen, then NBC's Vice President of Daytime Programming, moved the show out of the noontime slot where it had been located for most of its run, as part of her effort to boost ratings among the 18–34 female demographic.[99] After 2,753 episodes, the original Jeopardy! series ended on January 3, 1975; to compensate Griffin for its cancellation, NBC purchased Wheel of Fortune, another show that he had created, and premiered it the following Monday.[1] A syndicated edition of Jeopardy!, distributed by Metromedia and featuring many contestants who were previously champions on the original series, aired in the primetime during the 1974–1975 season.[100] The NBC daytime series was later revived as The All-New Jeopardy!, which premiered on October 2, 1978[101] and aired 108 episodes, ending on March 2, 1979;[102] this revival featured significant rule changes, such as progressive elimination of contestants over the course of the main game, and a bonus round instead of Final Jeopardy![5]

The daily syndicated version debuted on September 10, 1984,[103] and was launched in response to the success of the syndicated version of Wheel[104] and the installation of electronic trivia games in pubs and bars.[105] This version of the program has met with greater success than the previous incarnations; it has outlived 300 other game shows and become the second most popular game show in syndication (behind Wheel), averaging 25 million viewers per week. The show's most recent renewal, in May 2017, extends it through the 2019–2020 season.[51]

Countries with versions of Jeopardy! listed in yellow (the common Arabic-language version in light yellow)

Jeopardy! has spawned versions in many foreign countries throughout the world, including Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Russia, Denmark, Israel, and Australia.[106] The American syndicated version of Jeopardy! is also broadcast throughout the world, with international distribution rights handled by CBS Studios International.[107]

Three spin-off versions of Jeopardy! have been created. Rock & Roll Jeopardy! debuted on VH1 in 1998[108] and ran until 2001; the show centered around post-1950s popular music trivia and was hosted by Jeff Probst.[5]Jep!, which aired on GSN during the 1998–1999 season, was a special children's version hosted by Bob Bergen and featured various rule changes from the original version.[109]Sports Jeopardy!, a sports-themed version hosted by Dan Patrick, premiered in 2014 on the Crackle digital service and eventually moved to the cable sports network NBCSN in 2016.[110]

Archived episodes

Only a small number of episodes of the first three Jeopardy! versions survive. From the original NBC daytime version, archived episodes mostly consist of black-and-white kinescopes of the original color videotapes.[111] Various episodes from 1967, 1971, 1973, and 1974 are listed among the holdings of the UCLA Film and Television Archive.[112] The 1964 "test episode", Episode No. 2,000 (from February 21, 1972), and a June 1975 episode of the weekly syndicated edition exist at the Paley Center for Media.[113] Incomplete paper records of the NBC-era games exist on microfilm at the Library of Congress. GSN holds The All-New Jeopardy!'s premiere and finale in broadcast quality, and aired the latter on December 31, 1999, as part of its "Y2Play" marathon.[102] The UCLA Archive holds a copy of a pilot taped for CBS in 1977,[112] and the premiere exists among the Paley Center's holdings.[113]

GSN, which, like Jeopardy!, is an affiliate of Sony Pictures Television, has rerun ten seasons since the channel's launch in 1994. Copies of 43 Trebek-hosted syndicated Jeopardy! episodes aired between 1989 and 2004 have been collected by the UCLA Archive,[112] and the premiere and various other episodes are included in the Paley Center's collection.[113]

Reception

Alex Trebek with the Peabody Award, 2012

By 1994, the press called Jeopardy! "an American icon".[114] It has won a record 33 Daytime Emmy Awards.[115] The show holds the record for the Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Game/Audience Participation Show, with fifteen awards won in that category.[68] Another five awards have been won by Trebek for Outstanding Game Show Host.[68] Twelve other awards were won by the show's directors and writers in the respective categories of Outstanding Direction for a Game/Audience Participation Show and Outstanding Special Class Writing before these categories were removed in 2006. On June 17, 2011, Trebek shared the Lifetime Achievement Award with Sajak at the 38th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards ceremony.[116] The following year, the show was honored with a Peabody Award for its role in encouraging, celebrating, and rewarding knowledge.[117]

In its April 17–23, 1993 issue, TV Guide named Jeopardy! the best game show of the 1970s as part of a celebration of its 40th anniversary.[118] In January 2001, the magazine ranked the show number 2 on its "50 Greatest Game Shows" list—second only to The Price Is Right.[119] It would later rank Jeopardy! number 45 on its list of the 60 Best TV Series of All Time, calling it "habit-forming" and saying that the program "always makes [its viewers] feel smarter".[120] Also in 2013, the show ranked number 1 on TV Guide's list of the 60 Greatest Game Shows.[121] In the summer of 2006, the show was ranked number 2 on GSN's list of the 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time, second only to Match Game.[122]

A hall of fame honoring Jeopardy! was added to the Sony Pictures Studios tour on September 20, 2011. It features the show's Emmy Awards as well as retired set pieces, classic merchandise, video clips, photographs, and other memorabilia related to Jeopardy!'s history.[123]

In 1989, Fleming expressed dissatisfaction with the daily syndicated Jeopardy! series in an essay published in Sports Illustrated. He confessed that he only watched the Trebek version infrequently, and then only for a handful of questions; and also criticized this new iteration mainly for its Hollywood setting. Fleming believed that, in contrast to New Yorkers who Fleming considered to be more intelligent and authentic, moving the show to Hollywood brought both an unrealistic glamour and a dumbing-down of the program that he disdained. He also disliked the decision to not award losing contestants their cash earnings (believing the parting gifts offered instead to be cheap) and expressed surprise that what he considered to be a parlor game had transformed into such a national phenomenon under Trebek.[124]

Jeopardy!'s answer-and-question format has become widely entrenched: Fleming observed that other game shows would have contestants phrasing their answers in question form, leading hosts to remind them that they are not competing on Jeopardy![125]

Tournaments and other events

Regular events

Starting in 1985, the show has held an annual Tournament of Champions featuring the top fifteen champions who have appeared on the show since the last tournament. The top prize awarded to the winner was originally valued at $100,000,[106] and increased to $250,000 in 2003.[126] Other regular tournaments include the Teen Tournament, with a $100,000 top prize;[107] the College Championship, in which undergraduate students from American colleges and universities compete for a $100,000 top prize; and the Teachers Tournament, where educators compete for a $100,000 top prize.[127] Each tournament runs for ten consecutive episodes in a format devised by Trebek himself, consisting of five quarter-final games, three semifinals, and a final consisting of two games with the scores totaled.[39] Winners of the College Championship and Teachers Tournament are invited to participate in the Tournament of Champions.

Non-tournament events held regularly on the show include Celebrity Jeopardy!, in which celebrities and other notable individuals compete for charitable organizations of their choice;[128] and Kids Week, a special competition for school-age children aged 10 through 12.[129]

Special events

Three International Tournaments, held in 1996, 1997, and 2001, featured one-week competitions among champions from each of the international versions of Jeopardy!. Each of the countries that aired their own version of the show in those years could nominate a contestant. The format was identical to the semifinals and finals of other Jeopardy! tournaments.[80][106] In 1996 and 1997, the winner received $25,000; in 2001, the top prize was doubled to $50,000. The 1997 tournament was recorded in Stockholm on the set of the Swedish version of Jeopardy!, and is significant for being the first week of Jeopardy! episodes to be taped in a foreign country.[80]

There have been a number of special tournaments featuring the greatest contestants in Jeopardy! history. The first of these "all-time best" tournaments, Super Jeopardy!, aired in the summer of 1990 on ABC, and featured 35 top contestants from the previous seasons of the Trebek version and one notable champion from the original Jeopardy! series competing for a top prize of $250,000.[100] In 1993, that year's Tournament of Champions was followed by a Tenth Anniversary Tournament conducted over five episodes.[130] In May 2002, to commemorate the Trebek version's 4,000th episode, the show invited fifteen champions to play for a $1 million prize in the Million Dollar Masters tournament, which took place at Radio City Music Hall in New York City.[131] The Ultimate Tournament of Champions aired in 2005 and pitted 145 former Jeopardy! champions against each other, with two winners moving on to face Ken Jennings in a three-game final for $2,000,000, the largest prize in the show's history;[100] overall, the tournament spanned 15 weeks and 76 episodes, starting on February 9 and ending on May 25.[132] In 2014, Jeopardy! commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Trebek version with a Battle of the Decades tournament, in which 15 champions apiece from the first, second, and third decades of Jeopardy!'s daily syndicated history competed for a grand prize of $1,000,000.[133]

In November 1998, Jeopardy! traveled to Boston to reassemble 12 past Teen Tournament contestants for a special Teen Reunion Tournament.[96] In 2008, the 25th season began with reuniting 15 contestants from the first two Kids Weeks to compete in a special reunion tournament of their own.[134] During the next season (2009–2010), a special edition of Celebrity Jeopardy!, called the Million Dollar Celebrity Invitational, was played in which twenty-seven contestants from past celebrity episodes competed for a grand prize of $1,000,000 for charity; the grand prize was won by Michael McKean.[135]

The IBM Challenge aired February 14–16, 2011, and featured IBM's Watson computer facing off against Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter in a two-game match played over three shows.[136] This was the first man-vs.-machine competition in Jeopardy!'s history.[137] Watson won both the first game and the overall match to win the grand prize of $1 million, which IBM divided between two charities (World Vision International and World Community Grid).[138] Jennings, who won $300,000 for second place, and Rutter, who won the $200,000 third-place prize, both pledged to donate half of their winnings to charity.[139] The competition brought the show its highest ratings since the Ultimate Tournament of Champions.[140]

In 2019, The All-Star Games had six teams with three former champions each. Each team member played one of the three rounds in each game played. Rutter, David Madden and Larissa Kelly won the tournament.[141]

Record holders

Jeopardy!'s record for the longest winning streak is held by Ken Jennings, who competed on the show from June 2 through November 30, 2004, winning 74 matches before being defeated by Nancy Zerg in his 75th appearance. He amassed $2,520,700 over his 74 wins and a $2,000 second-place prize in his 75th appearance. At the time, he held the record as the highest money-winner ever on American game shows, and his winning streak increased the show's ratings and popularity to the point where it became TV's highest-rated syndicated program.[142] Jennings later won the $500,000 second-place prize in the 2005 Ultimate Tournament of Champions, the $300,000 second-place prize in the IBM Challenge, and the $100,000 second-place prize in the Battle of the Decades.

The highest-earning all-time Jeopardy! contestant is Brad Rutter, who has won a cumulative total of $4,355,102.[143] He became an undefeated champion in 2000 and later won an unprecedented four Jeopardy! tournaments: the 2001 Tournament of Champions,[144] the 2002 Million Dollar Masters Tournament, the 2005 Ultimate Tournament of Champions,[145] and the 2014 Battle of the Decades. Rutter broke Jennings's record for all-time game show winnings when he defeated Jennings and Jerome Vered in the Ultimate Tournament of Champions finals. Jennings regained the record through appearances on various other game shows, culminating in an appearance on Are You Smarter than a 5th Grader? on October 10, 2008. In 2014, Rutter regained the title after winning $1,000,000 in the Battle of the Decades, defeating Jennings and Roger Craig in the finals.

Craig is the holder of the all-time record for single-day winnings on Jeopardy!. On the episode that aired September 14, 2010, he amassed a score of $47,000 after the game's first two rounds, then wagered and won an additional $30,000 in the Final Jeopardy! round, finishing with $77,000. The previous single-day record of $75,000 had been set by Jennings.[146]

The record-holder among female contestants on Jeopardy!—in both number of games and total winnings—is Julia Collins, who amassed $429,100 over 21 games between April 21 and June 2, 2014. She won $428,100 in her 20 games as champion, plus $1,000 for finishing third in her twenty-first game.[147] Collins also achieved the second-longest winning streak on the show, behind Jennings. The streak, which was interrupted in May by the Battle of the Decades, was broken by Brian Loughnane.[148][149]

The highest single-day winnings in a Celebrity Jeopardy! tournament was achieved by comedian Andy Richter during a first-round game of the 2009–2010 season's "Million Dollar Celebrity Invitational", in which he finished with $68,000 for his selected charity, the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.[150]

Four contestants on the Trebek version have won a game with the lowest amount possible ($1). The first was U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Darryl Scott, on the episode that aired January 19, 1993;[151][152] the second was Benjamin Salisbury, on a Celebrity Jeopardy! episode that aired April 30, 1997;[153] the third was Brandi Chastain, on the Celebrity Jeopardy! episode that aired February 9, 2001;[154] and the fourth was U.S. Navy Lieutenant Manny Abell, on the episode that aired October 17, 2017.[152]

Other media

Portrayals and parodies

Jeopardy! has been featured in a number of films, television shows and books over the years, mostly with one or more characters participating as contestants, or viewing and interacting with the game show from their own homes.

- On "Questions and Answers", a season 7 episode of The Golden Girls aired February 8, 1992, Dorothy Zbornak (Bea Arthur) auditions for Jeopardy!, but despite her excellent show of knowledge, she is rejected by a contestant coordinator who feels that America would not root for her. In a dream sequence, Dorothy competes against roommate Rose Nylund (Betty White) and neighbor Charlie Dietz (David Leisure), in a crossover from Empty Nest. Trebek and Griffin appear as themselves in the dream sequence, and Gilbert provides a voice-over.[155]

- A 1988 episode of Mama's Family titled "Mama on Jeopardy!" features the titular Mama, Thelma Harper (Vicki Lawrence), competing on the show after her neighbor and friend Iola Boylan (Beverly Archer) is rejected.[156] For most of the game the questions given by Mama are incorrect, but she makes a miraculous comeback near the end and barely qualifies for Final Jeopardy! Her final question given is also incorrect, but she finishes in second place by $1 and wins a trip to Hawaii for herself and her family. Again, Trebek guest stars and Gilbert provides a voice-over.

- In the Cheers episode "What Is... Cliff Clavin?" (1990), the titular mailman, portrayed by John Ratzenberger, appears on the show and racks up an impressive $22,000 going into the Final Jeopardy! round, well ahead of his competitors. Despite having a total that his competitors cannot reach in Final Jeopardy!, Cliff risks all of his winnings on the final clue, which is revealed to be "Archibald Leach, Bernard Schwartz and Lucille LeSueur" (the real names of Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, and Joan Crawford, respectively). Cliff's response, "Who are three people who've never been in my kitchen?", is deemed incorrect, and he leaves with no money.[157]

- In "I Take Thee Quagmire", a season 4 episode of Family Guy aired March 12, 2006, Mayor Adam West appears as a contestant on Jeopardy!. He spells Trebek's name backwards (as "Kebert Xela"), "sending him back" to the fifth dimension, in reference to when Mister Mxyzptlk, a nemesis to DC Comics' Superman, is sent to the fifth dimension when someone makes him say his own name backwards.[158]

- Trebek appears as himself on "Miracle on Evergreen Terrace", a season 9 episode of The Simpsons in which Marge Simpson appears on a fictional version of the show, but performs very poorly, leaving with –$5,200. Trebek then demands Marge pay this amount to the show.[159]

- From 1996 to 2002 and again in 2005, 2009, and 2015, Saturday Night Live featured a recurring Celebrity Jeopardy! sketch in which Trebek, portrayed by Will Ferrell, has to deal with the exasperating ineptitude of the show's celebrity guests and the constant taunts of antagonists Sean Connery (played by Darrell Hammond) and Burt Reynolds (Norm Macdonald), the latter of whom at one point insists on being called "Turd Ferguson".[160]

- Since 2013, Saturday Night Live has included the recurring sketch Black Jeopardy!, in which the host and two of the three contestants are stereotypical black Americans and the categories and clues likewise reflect black American culture. The third contestant in Black Jeopardy! provides a contrast to the others, such as a professor of African-American studies, a Black Canadian, a white Donald Trump supporter, or the king of the fictional African nation of Wakanda.[161]

Jeopardy! is featured in a subplot of the 1992 film White Men Can't Jump, in which Gloria Clemente (Rosie Perez) attempts to pass the show's auditions.[162] She succeeds, and ends up appearing on the show, winning over $14,000.- The Univision Deportes program Fútbol Club features a segment similar to Jeopardy! named "Yoperdy!", the name itself a Spanish language parody of the Jeopardy! name.

- Other films and television series in which Jeopardy! has been portrayed over the years include The 'Burbs, Die Hard, Men in Black, Rain Man, Homeless to Harvard: The Liz Murray Story, Charlie's Angels, Dying Young, The Education of Max Bickford, The Bucket List, Groundhog Day, Predator 2, and Finding Forrester.[163]

- In the David Foster Wallace short story "Little Expressionless Animals", first published in The Paris Review and later reprinted in Wallace's collection Girl with Curious Hair, the character Julie Smith competes and wins on every Jeopardy! game for three years (a total of 700 episodes)[164] and then uses her winnings to pay for the care of her brother, who has autism.[165]

- The Ellen's Energy Adventure attraction at Epcot's Universe of Energy pavilion featured a dream sequence in which Ellen DeGeneres plays a Jeopardy! game entirely focused on energy.[166]

- Fleming makes a cameo appearance reprising his role as host of Jeopardy! in the 1982 film Airplane II: The Sequel.

- The music video "I Lost on Jeopardy", a parody of Greg Kihn's 1983 hit song "Jeopardy", was released by "Weird Al" Yankovic in 1984, a few months before Trebek's version debuted;[167] the video featured cameos from Fleming, Pardo, Kihn, and Dr. Demento.[168]

Merchandise

Over the years, the Jeopardy! brand has been licensed for various products. From 1964 through 1976, Milton Bradley issued annual board games based on the original Fleming version. The Trebek version has been adapted into board games released by Pressman Toy Corporation, Tyco Toys, and Parker Brothers.[169] In addition, Jeopardy! has been adapted into a number of video games released on various consoles and handhelds spanning multiple hardware generations, starting with a Nintendo Entertainment System game released in 1987.[170] The show has also been adapted for personal computers (starting in 1987 with Apple II, Commodore 64, and DOS versions[171]), Facebook,[172]Twitter, Android, and the Roku Channel Store.[173]

A DVD titled Jeopardy!: An Inside Look at America's Favorite Quiz Show, released by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment on November 8, 2005, features five memorable episodes of the Trebek version (the 1984 premiere, Jennings' final game, and the three finals matches of the Ultimate Tournament of Champions)[174] and three featurettes discussing the show's history and question selection process.[175] Other products featuring the Jeopardy! brand include a collectible watch, a series of daily desktop calendars, and various slot machine games for casinos and the Internet.

Internet

Jeopardy!'s official website, active as early as 1998,[176] receives over 400,000 monthly visitors.[177] The website features videos, photographs, and other information related to each week's contestants, as well as mini-sites promoting remote tapings and special tournaments. As the show changes its main title card and corresponding graphics with every passing season, the Jeopardy! website is re-skinned to reflect the changes, and the general content of the site (such as online tests and promotions, programming announcements, "spotlight" segments, photo galleries, and downloadable content) is regularly updated to align with producers' priorities for the show.[178] In its 2012 "Readers Choice Awards", About.com praised the official Jeopardy! website for featuring "everything [visitors] need to know about the show, as well as some fun interactive elements", and for having a humorous error page.[179]

In November 2009, Jeopardy! launched a viewer loyalty program called the "Jeopardy! Premier Club", which allowed home viewers to identify Final Jeopardy! categories from episodes for a chance to earn points, and play a weekly Jeopardy! game featuring categories and clues from the previous week's episodes. Every three months, contestants were selected randomly to advance to one of three quarterly online tournaments; after these tournaments were played, the three highest scoring contestants would play one final online tournament for the chance to win $5,000 and a trip to Los Angeles to attend a taping of Jeopardy![180] The Premier Club was discontinued by July 2011.[181]

There is an unofficial Jeopardy! fansite known as the "J! Archive" (j-archive.com), which transcribes games from throughout Jeopardy!'s daily syndicated history. In the archive, episodes are covered by Jeopardy!-style game boards with panels which, when hovered over with a mouse, reveal the correct response to their corresponding clues and the contestant who gave the correct response. The site makes use of a "wagering calculator" that helps potential contestants determine what amount is safest to bet during Final Jeopardy!, and an alternative scoring method called "Coryat scoring" that disregards wagering during Daily Doubles or Final Jeopardy! and gauges one's general strength at the game. The site's main founding archivist is Robert Knecht Schmidt, a student from Cleveland, Ohio,[182] who himself appeared as a Jeopardy! contestant in March 2010.[183] Before J! Archive, there was an earlier Jeopardy! fansite known as the "Jeoparchive", created by season 19 contestant Ronnie O'Rourke, who managed and updated the site until Jennings's run made her disillusioned with the show.[182]

References

^ ab Griffin & Bender 2003, p. 100.

^ ab "Jeopardy! 7,000". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.Tune in May 20th to celebrate with us.

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcde Schwartz, Ryan & Wostbrock 1999, pp. 112–115.

^ Zogbi, Emily (August 21, 2018). "What's Happening on 'Jeopardy'? Season 35 Promises Something Big". Newsweek.

^ abcdefghij Newcomb 2004, pp. 1222–1224.

^ Eisenberg 1993.

^ abc Harris 1998, p. 13.

^ "Show No. 3966 (Harold Skinner vs. Geoffrey Zimmermann vs. Kristin Lawhead)". Jeopardy!. November 26, 2001. Syndicated.

^ abcde Jeopardy! DVD Home Game System Instruction Booklet. MGA Entertainment. 2007.

^ Marchese, David (November 12, 2018). "In Conversation: Alex Trebek". Vulture.com. Retrieved November 13, 2018.What bothers me is when contestants jump all over the board even after the Daily Doubles have been dealt with. Why are they doing that? They’re doing themselves a disservice. When the show’s writers construct categories they do it so that there’s a flow in terms of difficulty, and if you jump to the bottom of the category you may get a clue that would be easier to understand if you’d begun at the top of the category and saw how the clues worked.

^ ab Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, pp. 59–60.

^ Richmond 2004, p. 41.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, pp. 2–3.

^ ab "5 Rules Every Jeopardy! Contestant Should Know". Jeopardy! Official Site. Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. 7 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 64.

^ Fabe 1979.

^ "Breaking Down Four Rare Jeopardy! Scenarios". Jeopardy! official website. 6 Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.In the event all three contestants have $0 (zero) or minus amounts at the end of Double Jeopardy!, no Final Jeopardy! round would be played.

^ Dutta 1999, p. xxix.

^ ab Gilbert, George T.; Hatcher, Rhonda L. (1 October 1994). "Wagering in Final Jeopardy!". Mathematics Magazine. 67 (4): 268. doi:10.2307/2690846.

^ Williams, Keith (2015-09-01). "Keith Williams on Wagering". Jeopardy! official website. Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

^ "Show No. 4089 (Ronnie O'Rourke vs. Ben Tritle vs. Allison Owens)". Jeopardy!. May 16, 2002. Syndicated.

^ Jennings 2006, p. 122.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 57.

^ Mogel, p. 148.

^ "Jeopardy! Premieres Milestone 20th Anniversary Season September 8, 2003: America's Favorite Quiz Show Launches Season 20 With Many Exciting and Historic "Firsts"" (Press release). King World. September 4, 2003. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

^ ab "'Jeopardy!' contestants tie, forcing rare sudden death clue". WGN-TV. 2 March 2018.

^ "Breaking Down Four Rare Jeopardy! Scenarios". Jeopardy! Official Site. Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

^ Higgins, Chris (2014-01-31). "6 Elements of Arthur Chu's Jeopardy! Strategy". Mental Floss. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

^ Kim, Susanna (2014-02-03). "'Hero-Villain' Jeopardy! Contestant Returns to Game Show Feb. 24". ABC News.

^ "Jeopardy! History is Made with First-Ever Three-Way Tie". Jeopardy! Official Site. Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. March 18, 2007. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

^ "Jeopardy! First: a Tiebreaker". www.jeopardy.com. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

^ "Show No. 2 (Greg Hopkins vs. Lynne Crawford vs. Paul Schaffer)". Jeopardy!. September 11, 1984. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 3190 (Steve Sosnick vs. Robert Levy vs. Marion Arkin)". Jeopardy!. June 12, 1998. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 7216 (Mike Drummond vs. Claudia Corriere vs. Randi Kristensen)". Jeopardy!. January 18, 2016. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 3116 (Teri Garr vs. Naomi Judd vs. Jane Curtin)". Jeopardy!. March 2, 1998. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 5611 (Michele Lee Amundsen vs. Lori Karman vs. Matt Kohlstedt)". Jeopardy!. January 19, 2009. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 5669 (Jeff Mangum vs. Priscilla Ball vs. Rick Robbins)". Jeopardy!. April 9, 2009. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 7196 (Shoshana Gordon Ginsburg vs. Jay O'Brien vs. Liz Quesnelle". Jeopardy!. December 21, 2015. Syndicated.

^ ab Eisenberg 1993, p. 75.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 174.

^ ab "Teen Tournament Semifinal Game 2 (Tori Amos vs. Joe Vertnik vs. Kelton Ellis)". Jeopardy!. February 7, 2013. Syndicated.

^ Lowry, Cynthia (March 29, 1964). "Merv Griffin: Question and Answer Man". Independent Star-News. Associated Press.

^ Lidz, Franz (1 May 1989). "What Is Jeopardy!'?". Sports Illustrated. Time Inc. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

^ ab Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 2.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 4.

^ Griffin & Bender 2003, p. 71.

^ Abelman 1998, p. 270.

^ Terrace 1985, p. 214.

^ ab Harris 1998, p. 14.

^ Encyclopedia of Observances, Holidays, and Celebrations. MobileReference. 2007. ISBN 978-1-60501-177-6.

^ ab Turnquist, Kristi. "'Jeopardy' and 'Wheel of Fortune' will return for 2019-2020 TV season". Oregon Live. The Oregonian/OregonLive. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

^ "Alex Trebek says there's a 50/50 chance he'll retire from 'Jeopardy'". Newsday/AP. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018.

^ "Alex Trebek Will Host 'Jeopardy' through 2022". People.com. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

^ "'I'm going to fight this': Jeopardy host Alex Trebek announces Stage 4 cancer". Associated Press. March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

^ "Jeopardy host Alex Trebek says he has Stage 4 pancreatic cancer'". Global News. March 6, 2019.

^ ab "Jeopardy! Names Clue Crew Members – Team of Roving Correspondents Debuts September 24" (Press release). King World. September 24, 2001. Archived from the original on August 4, 2002. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

^ ab Petrozzello, Donna (June 4, 2001). "Trebeks in Training Jeopardy! Auditions Roving Reps". New York Daily News.

^ "Jeopardy! Rings in the New Year Seeking New Clue Crew Member – "What's The Ultimate Dream Job For $500, Alex?"" (Press release). King World. January 6, 2005. Archived from the original on February 6, 2005. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

^ "Show 4826 (David Madden vs. Catie Camille vs. Willy Jay)". Jeopardy!. September 12, 2005. Syndicated.

^ "Show 5540 (Hannah Lynch vs. Luciano D'Orazio vs. Jim Davis)". Jeopardy!. October 10, 2008. Syndicated.

^ "Show 5735 (Kathleen O'Day vs. Peter Wiscombe vs. Alyssa McRae)". Jeopardy!. July 10, 2009. Syndicated.

^ "Meet the "Jeopardy!" Clue Crew". Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

^ "Jeopardy Cast and Crew Bios". Jeopardy! Official Site. Sony. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

^ abcdef Credits from various Jeopardy! episodes.

^ abc Richmond 2004, p. 239.

^ "This is JEOPARDY! – Show Guide – Bios – Harry Friedman". Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

^ "Clay Jacobsen named director of JEOPARDY!" (PDF). Sony Pictures Television. June 26, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

^ abc "This is JEOPARDY! – Show Guide – About the Show – Show History". Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

^ ab "Production Credits". Jeopardy! Official Site. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

^ Schwartz, Ryan & Wostbrock 1999.

^ Barnes, Mike (July 19, 2011). "Ed Flesh, Designer of the Wheel on Wheel of Fortune, Dies at 79". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

^ Gilbert, Tom (August 19, 2007). "Wheel of Fortune, Jeopardy!: Merv Griffin's True TV Legacy". TelevisionWeek. Archived from the original on July 25, 2007.

^ "Company Overview of Jeopardy Productions, Inc". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

^ "Pat, Vanna and Alex Play On!". Sony Pictures Television. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

^ NBC daily broadcast log, Master Books microfilm. Library of Congress Motion Picture and Television Reading Room.

^ Owen, Rob (November 15, 2018). "TV Q&A: 'Chicago Fire,' Hallmark Channel Christmas movies, 'Jeopardy!'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

^ ab Richmond 2004, p. 100.

^ abc "Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune go hi def!". Sony Pictures Television. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

^ ab "This is Jeopardy!—Show Guide—Virtual Set Tour". Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

^ abc Richmond 2004, p. 150.

^ Richmond 2004, p. 210.

^ "2003 Jeopardy! set official web page". Archived from the original on February 13, 2008.

^ Wong, Tony (July 19, 2013). "Alex Trebek Talks 30 Seasons of Jeopardy!". Toronto Star. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

^ "Classic Game Shows: Jeopardy! (Original Series)". tv.party.com. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

^ Barnes, Lindsay (August 16, 2007). "NEWS: Genesis of Jeopardy!: Who is Julann Griffin?". Readthehook.com.

^ "Merv Griffin soundtrack". ringostrack.com. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

^ Bickelhaupt, Susan (September 5, 1989). "Placing himself in Jeopardy! tonight", The Boston Globe, p. 54.

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 10.

^ Harris 1998, p. 17.

^ Richard Natale (August 12, 2007). "Hollywood legend Merv Griffin dies: Media mogul known for game shows, talk show". Variety. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

^ "For Merv Griffin, 14 Seconds Can Last a Lifetime". bmi.com. June 17, 2003. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

^ Game Show Awards (TV production). GSN. 2009.

^ Morin, Monte (December 17, 2003). "Pilot Killed in Crash Was TV, Film Composer; Steve Kaplan, who died when his plane crashed into a Claremont home, had written music for 'Jeopardy!' and 'Wheel of Fortune.'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

^ "Jeopardy!". Chris Bell Music and Sound Design. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

^ Fleming 1979, pp. 14–15.

^ ab Richmond 2004, p. 170.

^ "Jeopardy! - FAQs". www.jeopardy.com. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

^ Fabe 1979, p. 95.

^ Griffin & Bender 2003, p. 8.

^ abc Brooks & Marsh 2009, p. 696.

^ "Jeopardy! with Art Fleming (Introduction of Super Jeopardy! Board)". Paley Center for Media.

^ ab "Hosted By Game Show Great Charles Nelson Reilly, "Y2PLAY" To Air on GSN From 4:00 pm Through Midnight on Dec. 31, 1999". Business Wire. November 22, 1999.

^ Richmond 2004, pp. 12, 15, 33.

^ Griffin & Bender 2003, p. 106.

^ Jennings 2006, pp. 215, 220.

^ abc Harris 1998, p. 16.

^ ab "CBS Press Express: Jeopardy!". CBS Television Distribution. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

^ Austen 2005, p. 210.

^ Terrace 2011.

^ "Sony Making a Sports Version of Jeopardy!". Associated Press. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

^ Eisenberg 1993, p. 240.

^ abc "UCLA Library Catalog – Jeopardy!". UCLA Film and Television Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

^ abc "Jeopardy! at the Paley Center for Media". Retrieved January 7, 2013.

^ "Taking A Peek". Computer Gaming World. May 1994. pp. 174–180.

^ "Jeopardy!'s Emmy® Awards". Jeopardy!. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

^ "The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Announces the 38th Annual Daytime Emmy Award for Lifetime Achievement to Be Presented to Pat Sajak and Alex Trebek". Sony Pictures Entertainment. June 26, 2011. Archived from the original on March 26, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

^ "Complete List of Recipients of the 71st Annual Peabody Awards". The Peabody Awards: An International Competition for Electronic Media, honoring achievement in Television, Radio, Cable, and the Web, administered by the University of Georgia's Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. April 4, 2012. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

^ TV Guide April 17–23, 1993. 1993. p. 84.

^ "none". TV Guide. January 27 – February 2, 2001.

^ Fretts, Bruce; Roush, Matt (December 23, 2013). "TV Guide Magazine's 60 Best Series of All Time". TV Guide.

^ Fretts, Bruce (June 17, 2013). "Eyes on the Prize". TV Guide. pp. 14 and 15.

^ The 50 Greatest Game Shows of All Time (TV production). GSN.

^ "Jeopardy! Unveils New Hall of Fame Featuring Its Most Historic TV Moments". Sony Pictures Television. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

^ What is Jeopardy!?, 05.01.89 – Sports Illustrated

^ Trebek & Barsocchini 1990, p. 188.

^ "Show 4320 (Brian Weikle vs. Eric Floyd vs. Mark Dawson)". Jeopardy!. May 16, 2003. Syndicated.

^ "'Jeopardy!' to Mark 6,000th Episode Milestone During Season 27". TheFutonCritic.com. September 10, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

^ Richmond 2004, p. 110.

^ "Jeopardy! Hosts Its First-Ever Back to School Week for Kids". Columbia TriStar Interactive. September 6, 1999. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

^ Richmond 2004, p. 120.

^ Richmond 2004, p. 200.

^ "Jeopardy! Seeking Tournament of Champions Alumni". TVLatest.com. May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

^ "People and places: Let's try '80s champions' for $1M, Alex". Fairfax Times. January 31, 2014. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

^ "Jeopardy! Episode Guide 2008 – Kids Week Reunion, Day 1". TV Guide. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

^ "Actor Michael McKean Wins Jeopardy! Million Dollar Celebrity Invitational and Gives $1 Million Grand Prize to Charity: International Myeloma Foundation Receives Largest Single Donation Ever". Sony Pictures Digital and Jeopardy Productions. May 7, 2010. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

^ "Smartest Machine on Earth Episode 1". DocumentaryStorm. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

^ "IBM's "Watson" Computing System to Challenge All Time Greatest Jeopardy! Champions". December 14, 2010. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

^ "World Community Grid to benefit from Jeopardy! competition". World Community Grid. February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

^ Griggs, Brandon (February 15, 2011). "So far, it's elementary for Watson". CNN. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

^ Albiniak, Paige (February 17, 2011). "IBM's Watson: 'Jeopardy!' Champ, Ratings Winner: Three days of Watson-based episodes drives 'Jeopardy!' to six-year highs". Broadcasting & Cable. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

^ Westcott, Jay (March 1, 2019). "Had he said 'Pulp Fiction,' a Greensboro man and his All-Star team would still be on 'Jeopardy!'". News and Record. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

^ "Jeopardy! Streak Over: Ken Jennings Loses in 75th Game, Takes Home a Record-Setting $2,520,700" (Press release). King World. November 30, 2004. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

^ "'Jeopardy!' Battle of the Decades Tournament winner Brad Rutter wins $1 million grand prize". Zap2it. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

^ Stauffer, Cindy (May 1, 2002). "Manheim Twp. man back in 'Jeopardy!' in Million Dollar Masters Tournament". Lancaster New Era.

^ "A: He beat the best. Q: Who is Brad Rutter?". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 27, 2005.

^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 15, 2010). "Record Set On 'Jeopardy!'". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

^ "How Jeopardy Champion Julia Collins Will Spend Her Windfall". Kiplinger. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

^ Jeopardy!. Season 30. Episode 6821. 21 April 2014. Syndication.

^ Jeopardy!. Season 30. Episode 6851. 2 June 2014. Syndication.

^ "Million Dollar Celebrity Invitational, Game 1 (Andy Richter vs. Dana Delany vs. Wolf Blitzer)". Jeopardy!. September 17, 2009. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 1932 (Nancy Melucci vs. Darryl Scott vs. Kate Marciniak)". Jeopardy!. January 19, 1993. Syndicated.

^ ab "Jeopardy! Archive: $1 Winners". Jeopardy.com. Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

^ "Show No. 2928 (Joey Gordon-Levitt vs. Kirsten Dunst vs. Benjamin Salisbury)". Jeopardy!. April 30, 1997. Syndicated.

^ "Show No. 3790 (Seth Green vs. Brandi Chastain vs. Steven Page)". Jeopardy!. February 9, 2001. Syndicated.

^ "Questions and Answers". The Golden Girls. February 1992. NBC.

^ "Mama on Jeopardy!". Mama's Family. Season 4. Episode 23. 3 February 1988. Syndication.

^ Bjorklund 1997, p. 231.

^ MacFarlane, Seth (2005). Family Guy season 4 DVD commentary for the episode "I Take Thee Quagmire" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

^ "Miracle on Evergreen Terrace". BBC. September 2005. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

^ Collura, Scott; Pirrello, Phil (February 28, 2008). "Top 15 Will Ferrell Characters". IGN. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008.