Inheritance

From William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress. "The Young Heir Takes Possession Of The Miser's Effects".

Inheritance is the practice of passing on property, titles, debts, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 History

2.1 Jewish laws

2.2 Christian laws

2.3 Islamic laws

3 Inequality

3.1 Social stratification

3.2 Sociological and economic effects of inheritance inequality

3.3 Dynastic wealth

4 Taxation

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Terminology

In law, an heir is a person who is entitled to receive a share of the deceased's (the person who died) property, subject to the rules of inheritance in the jurisdiction of which the deceased was a citizen or where the deceased (decedent) died or owned property at the time of death.

The inheritance may be either under the terms of a will or by intestate laws if the deceased had no will. However, the will must comply with the laws of the jurisdiction at the time it was created or it will be declared invalid (for example, some states do not recognize holographic wills as valid, or only in specific circumstances) and the intestate laws then apply.

A person does not become an heir before the death of the deceased, since the exact identity of the persons entitled to inherit is determined only then. Members of ruling noble or royal houses who are expected to become heirs are called heirs apparent if first in line and incapable of being displaced from inheriting by another claim; otherwise, they are heirs presumptive. There is a further concept of joint inheritance, pending renunciation by all but one, which is called coparceny.

In modern law, the terms inheritance and heir refer exclusively to succession to property by descent from a deceased dying intestate. Takers in property succeeded to under a will are termed generally beneficiaries, and specifically devisees for real property, bequestees for personal property (except money), or legatees for money.

Except in some jurisdictions where a person cannot be legally disinherited (such as the United States state of Louisiana, which allows disinheritance only under specifically enumerated circumstances), a person who would be an heir under intestate laws may be disinherited completely under the terms of a will (an example is that of the will of comedian Jerry Lewis; his will specifically disinherited his six children by his first wife, and their descendants, leaving his entire estate to his second wife).

History

Detailed anthropological and sociological studies have been made about customs of patrilineal inheritance, where only male children can inherit. Some cultures also employ matrilineal succession, where property can only pass along the female line, most commonly going to the sister's sons of the decedent; but also, in some societies, from the mother to her daughters. Some ancient societies and most modern states employ egalitarian inheritance, without discrimination based on gender and/or birth order.

Jewish laws

The inheritance is patrilineal. The father —that is, the owner of the land— bequeaths only to his male descendants, so the Promised Land passes from one Jewish father to his sons.

If there were no living sons and no descendants of any previously living sons, daughters inherit. In Numbers 27:1-4, the daughters of Zelophehad (Mahlah, Noa, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah) of the tribe of Manasseh come to Moses and ask for their father's inheritance, as they have no brothers. The order of inheritance is set out in Numbers 27:7-11: a man's sons inherit first, daughters if no sons, brothers if he has no children, and so on.

Later, in Numbers 36, some of the heads of the families of the tribe of Manasseh come to Moses and point out that, if a daughter inherits and then marries a man not from her paternal tribe, her land will pass from her birth-tribe's inheritance into her marriage-tribe's. So a further rule is laid down: if a daughter inherits land, she must marry someone within her father's tribe. (The daughters of Zelophehad marry the sons' of their father's brothers. There is no indication that this was not their choice.)

The tractate Baba Bathra, written during late Antiquity in Babylon, deals extensively with issues of property ownership and inheritance according to Jewish Law. Other works of Rabbinical Law, such as the Hilkhot naḥalot : mi-sefer Mishneh Torah leha-Rambam,[1] and the Sefer ha-yerushot: ʻim yeter ha-mikhtavim be-divre ha-halakhah be-ʻAravit uve-ʻIvrit uve-Aramit[2] also deal with inheritance issues. The first, often abbreviated to Mishneh Torah, was written by Maimonides and was very important in Jewish tradition.

All these sources agree that the firstborn son is entitled to a double portion of his father's estate: Deuteronomy 21:17. This means that, for example, if a father left five sons, the firstborn receives a third of the estate and each of the other four receives a sixth. If he left nine sons, the firstborn receives a fifth and each of the other eight receive a tenth.[1][3] If the eldest surviving son is not the firstborn son, he is not entitled to the double portion.

Philo of Alexandria[4] and Josephus[5] also comment on the Jewish laws of inheritance, praising them above other law codes of their time. They also agreed that the firstborn son must receive a double portion of his father's estate.

Christian laws

The New Testament does not specifically mention anything about inheritance rights: the only story even mentioning inheritance is that of the Prodigal Son, but that involved the father voluntarily passing his estate to his two sons prior to his death; the younger son receiving his inheritance (1/3; the older son would have received 2/3 under then existing Jewish law) and squandering it.

The topic is generally not discussed among doctrinal statements of various denominations or sects, leaving that to be a matter of secular concern.

Islamic laws

The Quran introduced a number of different rights and restrictions on matters of inheritance, including general improvements to the treatment of women and family life compared to the pre-Islamic societies that existed in the Arabian Peninsula at the time.[6] Furthermore, the Quran introduced additional heirs that were not entitled to inheritance in pre-Islamic times, mentioning nine relatives specifically of which six were female and three were male. However, the inheritance rights of women remained inferior to those of men because in Islam someone always has a responsibility of looking after a woman's expenses. According to the Quran, for example, a son is entitled to twice as much inheritance as a daughter.[Quran 4:11][7] The Quran also presented efforts to fix the laws of inheritance, and thus forming a complete legal system. This development was in contrast to pre-Islamic societies where rules of inheritance varied considerably.[6] In addition to the above changes, the Quran imposed restrictions on testamentary powers of a Muslim in disposing his or her property. In their will, a Muslim can only give out a maximum of one third of their property.

The Quran contains only three verses that give specific details of inheritance and shares, in addition to few other verses dealing with testamentary. [Quran 4:11,12,176][8] But this information was used as a starting point by Muslim jurists who expounded the laws of inheritance even further using Hadith, as well as methods of juristic reasoning like Qiyas. Nowadays, inheritance is considered an integral part of Sharia law and its application for Muslims is mandatory, though many peoples (see Historical inheritance systems), despite being Muslim, have other inheritance customs.

Inequality

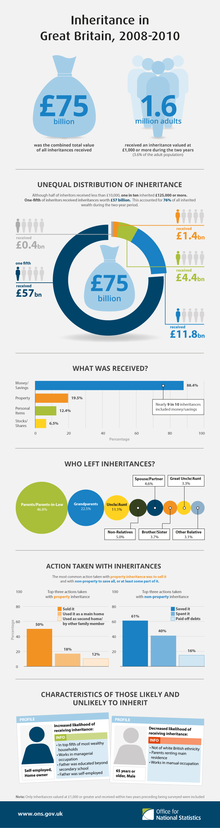

Inheritance by amount and distribution received and action taken with inheritances in Great Britain between 2008 and 2010

The distribution of the inherited wealth has varied greatly among different cultures and legal traditions. In nations using civil law, for example, the right of children to inherit wealth from parents in pre-defined ratios is enshrined in law,[9] as far back as the Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BC).[10] In the US State of Louisiana, the only US state to use Napoleonic Code for state law, this system is known as "forced heirship" which prohibits disinheritance of adult children except for a few narrowly-defined reasons that a parent is obligated to prove.[11] Other legal traditions, particularly in nations using common law, allow inheritances to be divided however one wishes, or to disinherit any child for any reason.

In cases of unequal inheritance, the majority might receive little while only a small number inherit a larger amount, with the lesser amount given to the daughter in the family.[citation needed] The amount of inheritance is often far less than the value of a business initially given to the son, especially when a son takes over a thriving multimillion-dollar business, yet the daughter is given the balance of the actual inheritance amounting to far less than the value of business that was initially given to the son. This is especially seen in old world cultures, but continues in many families to this day.[12]

Arguments for eliminating the disparagement of inheritance inequality include the right to property and the merit of individual allocation of capital over government wealth confiscation and redistribution, but this does not resolve what some[who?] describe as the problem of unequal inheritance. In terms of inheritance inequality, some economists and sociologists focus on the inter generational transmission of income or wealth which is said to have a direct impact on one's mobility (or immobility) and class position in society. Nations differ on the political structure and policy options that govern the transfer of wealth.[13]

According to the American federal government statistics compiled by Mark Zandi in 1985, the average US inheritance was $39,000. In subsequent years, the overall amount of total annual inheritance more than doubled, reaching nearly $200 billion. By 2050, there will be an estimated $25 trillion inheritance transmitted across generations.[14]

Some researchers have attributed this rise to the baby boomer generation. Historically, the baby boomers were the largest influx of children conceived after WW2. For this reason, Thomas Shapiro suggests that this generation "is in the midst of benefiting from the greatest inheritance of wealth in history."[15] Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start".[16][17] In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, "over 60 percent" of the Forbes richest 400 Americans "grew up in substantial privilege", and often (but not always) received substantial inheritances.[18] The French economist Thomas Piketty studied this phenomenon in his best-selling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2013.

Other research has shown that many inheritances, large or small, are rapidly squandered.[19] Similarly, analysis shows that over two-thirds of high-wealth families lose their wealth within two generations, and almost 80% of high-wealth parents "feel the next generation is not financially responsible enough to handle inheritance."[20]

Social stratification

It has been argued that inheritance plays a significant effect on social stratification. Inheritance is an integral component of family, economic, and legal institutions, and a basic mechanism of class stratification. It also affects the distribution of wealth at the societal level. The total cumulative effect of inheritance on stratification outcomes takes three forms, according to scholars who have examined the subject.

The first form of inheritance is the inheritance of cultural capital (i.e. linguistic styles, higher status social circles, and aesthetic preferences).[21] The second form of inheritance is through familial interventions in the form of inter vivos transfers (i.e. gifts between the living), especially at crucial junctures in the life courses. Examples include during a child's milestone stages, such as going to college, getting married, getting a job, and purchasing a home.[21] The third form of inheritance is the transfers of bulk estates at the time of death of the testators, thus resulting in significant economic advantage accruing to children during their adult years.[22] The origin of the stability of inequalities is material (personal possessions one is able to obtain) and is also cultural, rooted either in varying child-rearing practices that are geared to socialization according to social class and economic position. Child-rearing practices among those who inherit wealth may center around favoring some groups at the expense of others at the bottom of the social hierarchy.[23]

Sociological and economic effects of inheritance inequality

It is further argued that the degree to which economic status and inheritance is transmitted across generations determines one's life chances in society. Although many have linked one's social origins and educational attainment to life chances and opportunities, education cannot serve as the most influential predictor of economic mobility. In fact, children of well-off parents generally receive better schooling and benefit from material, cultural, and genetic inheritances.[24] Likewise, schooling attainment is often persistent across generations and families with higher amounts of inheritance are able to acquire and transmit higher amounts of human capital. Lower amounts of human capital and inheritance can perpetuate inequality in the housing market and higher education. Research reveals that inheritance plays an important role in the accumulation of housing wealth. Those who receive an inheritance are more likely to own a home than those who do not regardless of the size of the inheritance.[25]

Often, racial or religious minorities and individuals from socially disadvantaged backgrounds receive less inheritance and wealth.[citation needed] As a result, mixed races might be excluded in inheritance privilege and are more likely to rent homes or live in poorer neighborhoods, as well as achieve lower educational attainment compared with whites in America. Individuals with a substantial amount of wealth and inheritance often intermarry with others of the same social class to protect their wealth and ensure the continuous transmission of inheritance across generations; thus perpetuating a cycle of privilege.

Nations with the highest income and wealth inequalities often have the highest rates of homicide and disease (such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension).[26] A The New York Times article reveals that the U.S. is the world's wealthiest nation, but "ranks twenty-ninth in life expectancy, right behind Jordan and Bosnia." This has been regarded as highly attributed to the significant gap of inheritance inequality in the country,[27] although there are clearly other factors such as the affordability of healthcare.

When social and economic inequalities centered on inheritance are perpetuated by major social institutions such as family, education, religion, etc., these differing life opportunities are argued to be transmitted from each generation. As a result, this inequality is believed to become part of the overall social structure.[28]

Dynastic wealth

Dynastic wealth is monetary inheritance that is passed on to generations that didn't earn it.[29] Dynastic wealth is linked to the term Plutocracy. Much has been written about the rise and influence of dynastic wealth including the bestselling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century by the French economist Thomas Piketty.[30]

Bill Gates uses the term in his article "Why Inequality Matters".[31]

Taxation

Many states have inheritance taxes or death duties, under which a portion of any estate goes to the government.

See also

- Beneficiary

- Digital inheritance

- Family law

- Inheritance law in Canada

- Intra-household bargaining

- Old money

- Order of succession

- Pubilla

- Transformative asset

References

^ ab "Nachalot - Chapter 2". www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Saʻadia ben Joseph, Joel Müller (28 September 1897). "Sefer ha-yerushot: ʻim yeter ha-mikhtavim be-divre ha-halakhah be-ʻAravit uve-ʻIvrit uve-Aramit". Ernest Leroux. Retrieved 28 September 2017 – via Internet Archive.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-04-02.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Spec. Leg. 2.130

^ Ant. 4.249

^ ab C.E. Bosworth et al, eds. (1993). "Mīrāth". Encyclopaedia of Islam. 7 (second ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ "The Quranic Arabic Corpus - Translation". corpus.quran.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

^ [1] Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

^ Julia Twigg and Alain Grand. Contrasting legal conceptions of family obligation and financial reciprocity in the support of older people: France and England Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine Ageing & Society, 18(2) March 1998 , pp. 131-146

^ Edmond N. Cahn. Restraints on Disinheritance University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register, Vol. 85, No. 2 (Dec., 1936), pp. 139-153

^ 43 Loy. L. Rev. 1 (1997-1998)

The New Forced Heirship in Louisiana: Historical Perspectives, Comparative Law Analyses and Reflections upon the Integration of New Structures into a Classical Civil Law System Archived 2018-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

^ Davies, James B. "The Relative Impact of Inheritance and Other Factors on Economic Inequality". The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 97, No. 3, pp. 471

^ Angel, Jacqueline L. Inheritance in Contemporary America: The Social Dimensions of Giving across Generations. p. 35

^ Marable, Manning. "Letter From America: Inheritance, Wealth and Race." Google pages.com Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

^ Shapiro, Thomas M. The Hidden Cost of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 5

^ Bruenig, Matt (March 24, 2014). "You call this a meritocracy? How rich inheritance is poisoning the American economy". Salon. Archived from the original on July 31, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

^ Staff (March 18, 2014). "Inequality – Inherited wealth". The Economist. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

^ Pizzigati, Sam (September 24, 2012). "The 'Self-Made' Hallucination of America's Rich". Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

^ Elizabeth O'Brien. One in three Americans who get an inheritance blow it Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Market Watch.com

^ Chris Taylor. 70% of Rich Families Lose Their Wealth by the Second Generation Archived 2018-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, Time.com, June 17, 2015

^ ab (Edited By) Miller, Robert K., McNamee, Stephen J. Inheritance and Wealth in America. p. 2

^ (Edited By) Miller, Robert K., McNamee, Stephen L. Inheritance and Wealth in America. p. 4

^ Clignet, Remi. Death, Deeds, and Descendants: Inheritance in Modern America. p. 3

^ Bowles, Samuel; Gintis, Herbert, "The Inheritance of Inequality." Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 16, No. 3, 2002, p. 4

^ Flippen, Chenoa A. "Racial and Ethnic Inequality in Homeownership and Housing Equity." The Sociological Quarterly, Volume 42, No. 2 p. 134

^ page 20 of "The Spirit Level"by Wilkinson & Pickett, Bloomsbury Press 2009

^ Dubner, Stephen. "How Big of a Deal Is Income Inequality? A Guest Post". The New York Times. August 27, 2008.

^ Rokicka, Ewa. "Local policy targeted at reducing inheritance of inequalities in European countries." May 2006. Lodz.pl Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine (in Polish)

^ John J. Miller, "Open the FloodGates", "The Wall Street Journal", July 7, 2006

^ Piketty, Thomas, "Capital in the Twenty-First Century". Harvard University Press, Mar 10, 2014

^ BILL GATES, "Why Inequality Matters", "LinkedIn", 15 October 2014

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Inheritance |

. Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

. Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

- 26 July 2006 USA Today article on dilemma the rich face when leaving wealth to children