George Washington and slavery

George Washington and slavery

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

George Washington (John Trumbull, 1780), also depicts William Lee, Washington's enslaved personal servant, who for many years spent more time in Washington's presence than any other man.

In U.S. history, the relationship between George Washington and slavery was a complex one in that, while he held people as slaves for virtually all of his life, he expressed reservations about the institution during his career.

During Washington's presidency, increasing abolitionist sentiments in the U.S. caused him to have misgivings about his own slave ownership. Though publicly Washington said little against the institution, privately he expressed a belief that slavery's end would ultimately be necessary for the nation's survival. He supported legislation both supporting slavery (e.g. the Fugitive Slave Act) and restricting it (e.g. the Northwest Ordinance).

Washington's will included manumission for the enslaved people he held upon the death of his widow Martha Washington. She freed her husband's slaves in January 1801, just over a year after his death.[1] However, while she lived, Martha did not emancipate any of the slaves she herself owned. When she died, on May 22, 1802, at the age of 70, all of those enslaved people went to the descendants of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis.[2]

Contents

1 Washington's background

2 Revolutionary period

3 Postwar conditions

4 Presidency

5 Posthumous emancipation

6 Notable individuals enslaved by Washington

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Sources

Washington's background[edit]

When George Washington was eleven years old, he inherited ten slaves;[3] by the time of his death, 317 slaves lived at Mount Vernon,[4] including 123 owned by Washington, 40 leased from a neighbor, and an additional 153 "dower slaves." While these dower slaves were designated for Martha's use during her lifetime, they were part of the estate of her first husband Daniel Parke Custis, and the Washingtons could not sell or manumit them.[5] As on other plantations during that era, Washington's slaves worked from dawn until dusk unless injured or ill; they could be whipped for running away or for other infractions.

Visitors recorded varying impressions of slave life at Mount Vernon: one visitor in 1798 wrote that Washington treated his slaves "with more severity" than his neighbors, while another around the same time stated that "Washington treat[ed] his slaves far more humanely than did his fellow citizens of Virginia."[6]

Though Washington considered himself benevolent as a slave master, he did not tolerate suspected shirkers, even among those who were pregnant, old, or crippled. When a slave in an arm sling pleaded that it kept him from working, Washington demonstrated how to use a rake with one arm and scolded him, saying, "If you use your hand to eat, why can't you use it to work?" He would ship stubbornly disobedient slaves, such as one man named Waggoner Jack, to the West Indies, where the tropical climate and relentless toil tended to shorten life. Washington urged one of his estate managers persistently to keep an 83-year-old slave named Gunner hard at work to "continue throwing up brick earth". When the Potomac River froze over for five weeks in 1788, and with nine inches of snow on the ground, Washington kept them at exhausting outdoor labor, such as sending the female slaves to dig up tree stumps from a frozen swamp. After his own heading out during this unusually frigid weather to inspect his farms, Washington wrote in his diary that, "finding the cold disagreeable I returned".[7]

Washington was convinced slavery was economically unsound for the country.[8][9]

Revolutionary period[edit]

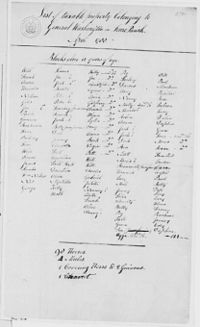

List of taxable property belonging to General Washington in Truro Parish, April 1788. Tax list with names of Washington's slaves, along with 98 horses, 4 mules and a chariot.

Before the American Revolution, Washington expressed no moral reservations about slavery, but by 1778 he had stopped selling slaves because he did not want to break up their families. The historian Henry Wiencek speculates that Washington's slave buying, particularly his participation in a raffle of 55 slaves in 1769, may have initiated a gradual reassessment of slavery. According to Wiencek, his thoughts on slavery may have also been influenced by the rhetoric of the American Revolution, the example of the thousands of blacks who enlisted in the army to fight for independence, the anti-slavery sentiments of his idealistic aide John Laurens, and his knowledge of the ability of the enslaved black poet Phillis Wheatley, who in 1775 wrote a poem in his honor.[10]

Washington and his wife were strict as slaveowners. "There are few Negroes who will work unless there be a constant eye on them," Washington advised one overseer, warning of their "idleness and deceit" unless treated firmly. When their "bondmen and women did flee", Washington and his wife appeared to consider them as "disloyal ingrates". In 1766, tired of a slave who ran away once too often, Washington wrote to Captain John Thompson, asking him to sell one Washington's slaves, whom he described as "a rogue and a run-away". Expressing little concern for the slave's comfort, Washington recommended that Thompson keep him "handcuffed until you get to sea or in the bay."[11][12] When, to Washington's humiliation, some of his slaves ran away during the Revolutionary War to find protection with the enemy, Washington did not cease trying to "reclaim what he saw as his property". According to one contemporary British memo, after the war, Washington demanded the return of escaped slaves "with all the grossness and ferocity of a captain of banditti".[7] The British refused to take the dishonorable step of returning the slaves as this would be a breach of faith, "delivering them up, some possibly to execution, and others to severe punishment."[13]

Wiencek also notes that in 1778, while Washington was at war, he wrote to his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished to sell his slaves and "to get quit of negroes", since maintaining a large (and increasingly elderly) slave population was no longer economically efficient. Washington could not legally sell his wife's "dower slaves" and, because they had long intermarried with his own slaves, he dropped the plan for sales in order to avoid breaking up families, which he had resolved not to do.[14]

At the end of the War, the British sought to evacuate their soldiers, including the Black Company of Pioneers who fought on their side and secured their freedom as a result. Washington opposed this measure, and tried in vain to force the British to give the Pioneers back to their former American owners.[15]

Postwar conditions[edit]

In 1782 the Virginia legislature made manumissions easier, while requiring documentation. Slaveholders were allowed to free any adult slave under the age of forty-five, either by executing a deed or adding provisions to a will.[16][17] So many slaveholders freed slaves in the next two decades that the percentage of free blacks went up to 7.2 percent of all blacks in Virginia by 1810, from less than one percent when the bill was passed.[18]

With the rise in demand for slaves after the invention of the cotton gin at the end of the century and the end of importation of slaves in 1808, Virginia changed its laws to make manumission more difficult. By the 1820s, it required legislative approval for each act of manumission.[citation needed] After 1810 manumissions dropped sharply.[19]

In 1793, when one of his estate managers, Anthony Whitting, whipped a slave named Charlotte, Washington was in full approval. His wife, Martha had deemed her to be "indolent". Washington wrote, "Your treatment of Charlotte was very proper," ... "and if she or any other of the servants will not do their duty by fair means, or are impertinent, correction (as the only alternative) must be administered." Another of his estate managers, Hiland Crow, was widely known for flogging slaves brutally.[7]

After the war, Washington often privately expressed a dislike of the institution of slavery. In 1786, he wrote to a friend that "I never mean ... to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." To another friend he wrote that "there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see some plan adopted for the abolition" of slavery. He expressed moral support for plans by his friend the Marquis de Lafayette to emancipate slaves and resettle them elsewhere, but he did not assist him in the effort.[20]

Washington was one of the wealthiest slave holders in Virginia and wealthiest persons in the country. [21] Washington owned 36,000 acres of land in Virginia and Maryland, and had securities in banks and land companies. [21] By 1783, Washington had 216 slaves under his control, that he either owned or were owned by his wife. [21] Washington's slaves afforded his luxurious lifestyle, including washing and sewing his clothes, polishing his boots, chopping wood, and powdering his hair; contrary to popular belief, Washington did not wear a wig.[21][22]

He held more slaves than he needed at Mount Vernon, making the operation unprofitable. The changes from tobacco to mixed-crop production lowered the labor needs. Washington wrote, "It is demonstratively clear that on this Estate (Mount Vernon) I have more working Negroes by a full [half] than can be employed to any advantage in the farming system." Washington could have sold his "surplus" slaves and immediately have realized a substantial revenue.[23] Washington acknowledged the profit he could make by reducing the number of his slaves, declaring, "half the workers I keep on this estate would render me greater net profit than I now derive from the whole."[24] However, in 1786 Washington accepted five slaves in payment of a debt owed to him by the Mercer family. A year later, he wrote to Henry Lee, asking him to purchase a slave trained as a bricklayer on his behalf.[25][26]

Presidency[edit]

The slave burial ground at Washington's Mount Vernon

Congress passed and President Washington signed the Northwest Ordinance of 1789, which was a reaffirmation of a 1787 act that had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory in 1789; slaves already in the territory, however, were not freed.[27] In 1790, Washington signed the Naturalization Act, providing a means for foreigners to become citizens. This act limited U.S. citizenship to "free white persons". At the time, these were Europeans. In later years of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in tests of definitions by Asians seeking citizenship, those persons considered white were classified as Caucasian according to the terms of the time.[28]

In 1793, President Washington signed the Fugitive Slave Act. This act, which implemented the Fugitive Slave Clause in the United States Constitution, gave slaveholders the right to capture fugitive slaves in any U.S. state. The act was passed to allow the recapture of fugitive slaves who escaped into any "safe harbors" or slave sanctuaries.[29] In 1794, Washington signed into law the first Slave Trade Act, which limited American involvement in the international slave trade.[30]

According to the historian Alfred Hunt, Washington authorized $400,000 and 1,000 weapons to be given to slaveholders of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (later Haiti) as emergency relief in 1793–1794 in order to put down a slave rebellion. The monetary relief and weapons counted as a repayment for loans granted by France to the Americans during the Revolutionary War.[31] The slaves continued to rebel and gained independence and freedom as Haiti in 1804.

Privately, Washington employed a shrewd strategy that permitted him to avoid the effects of slavery's gradual abolition in Pennsylvania, where from 1790 to 1800 the capital was located in Philadelphia. In 1780, Pennsylvania began to abolish slavery through a program of gradual emancipation. Slaveholders were still allowed to bring slaves into the state, but if they became residents, the slaves would become free. Typical of southern slaveholders serving in the city, Washington evaded the state's prohibition of slavery by maintaining that he was not a resident, and ensuring that neither he nor his eight or nine slaves stayed in the state for more than six months at a time. Two of his slaves escaped in Philadelphia. When one woman, Ona Judge (also known as Oney Judge,) made it to freedom in New Hampshire, Washington engaged in a three-year-long effort to recapture her.[32][33] Judge was never caught, and she later in life told people that she was inspired to escape by the ideals of the American Revolution.[34] In 1791, he shipped "misbehaving" slaves to the West Indies, selling one recalcitrant slave for "one pipe and quarter cask of wine from the West Indies".[35][36] In 1797, when his runaway slave cook, Hercules, was returned, Washington demoted him to a field slave, and bought a new slave cook to replace him. Washington also expressed the view that when his slaves claimed to be sick, they were often "lazy" and "idle".[37][38][39]

Acknowledging Philadelphia's Quaker abolitionist sentiment, Washington gradually replaced his slaves with German indentured servants.[40]

Washington expressed other concerns over slavery's implications for the nation. In 1797, Washington is reported to have told a British guest: "I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union, by consolidating it in a common bond of principal."[41] He told Edmund Randolph, according to Thomas Jefferson's notes, that if the country were to split over slavery, Washington "had made up his mind to move and be of the northern."[42] However, Washington believed that black people were incapable of understanding what freedom entailed. In 1798, he justified keeping black slaves by telling John Bernard that, "Till the mind of the slave has been educated to perceive what are the obligations of a state of freedom, and not confound a man’s with a brute’s, the gift would insure its abuse."[43]

Since the discovery in 2001 of the foundations of the President's house and slave quarters on Independence Mall, exhibits about slavery and the republic were added to the nearby Liberty Bell Center, which opened in 2003. In addition, a public archeology project was undertaken on the site in 2007, and a commemorative exhibit has been constructed at the site. The President's House in Philadelphia: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation opened in 2010.[44]

Posthumous emancipation[edit]

Slave memorial at Mount Vernon

Washington was the only Southern slaveholding Founding Father among the top seven[a]

to emancipate his slaves after the American Revolution. Of the seven Founding Fathers, the northerners Benjamin Franklin and John Jay both owned slaves whom they freed, and Jay founded the New York Manumission Society.[46] He had a practice of freeing slaves as adults after a period of service. In 1798, the year before New York passed its gradual emancipation law, Jay still owned six slaves.[47]

As Washington's slaves had intermarried with his wife's dower slaves, he included a provision in his will to free his slaves upon her death, to postpone any breakup of their families, when her dower slaves would be returned or managed by her heirs. He freed only William Lee, his longtime personal valet, outright in his will. The will called for the ex-slaves to be provided for by Washington's heirs, with the elderly ones to be clothed and fed, and the younger ones to be educated and trained at an occupation so they could support themselves. Martha Washington freed her husband's slaves within 12 months of his death and allowed them to stay at Mount Vernon if they had family members.[48]

Prior to 1782, Virginia law had limits on slaveholders emancipating slaves; they were only allowed to do so for "meritorious service" and only with the approval of the Governor and his council. This law was repealed by the 1782 law allowing slave emancipation by will or deed.[49]

Washington's failure to act publicly upon his growing private misgivings about slavery during his lifetime is seen by some historians as a missed opportunity. Historian Ellen Glasgow points out that Washington was "not exempt from employing the cruelty that was essential in maintaining a system based on slave labor."[50][51] The major reason Washington did not emancipate his slaves after the 1782 law and prior to his death was because of the financial costs involved.[52] To circumvent this problem, in 1794 he quietly sought to sell off his western lands and lease his outlying farms in order to finance the emancipation of his slaves, but this plan fell through because not enough buyers and renters could be found. Also, Washington did not want to risk splitting the new nation apart over the slavery issue. "He did not speak out publicly against slavery", argues historian Dorothy Twohig, "because he did not wish to risk splitting apart the young republic over what was already a sensitive and divisive issue."[53]

Notable individuals enslaved by Washington[edit]

Part of a series on Slavery |

|---|

|

Contemporary

|

Historical

|

By country or region

|

Religion

|

Opposition and resistance

|

Related

|

Harry Washington – he escaped to become a Black Loyalist during the American Revolutionary War, joining the British.[54]

- Deborah Squash – with her husband Harvey escaped from Mount Vernon; they went to New York where they joined the British during the American Revolutionary War and were evacuated in 1783 as freedmen.[55]

Hercules (chef), cook at President's House in Philadelphia, escaped from there, leaving family at Mount Vernon.[56]

Oney Judge – escaped slavery in Philadelphia from the President's house, but had to leave family at Mount Vernon.[56]

William (Billy) Lee – the only one of Washington's slaves freed outright by Washington in his will. Because he served by Washington's side throughout the American Revolutionary War and was sometimes depicted next to Washington in paintings, Lee was one of the most publicized African Americans of his time.[57]

Christopher Sheels – valet to the President in Philadelphia and Mount Vernon who was present at Washington's deathbed.

Nancy Quander and Sukey Bay – spinners and farm hands at Mount Vernon who were members of one of the oldest African families in North America.

See also[edit]

- Abraham Lincoln and slavery

- Thomas Jefferson and slavery

- List of Presidents of the United States who owned slaves

- John Quincy Adams and abolitionism

Notes[edit]

^ Historian Richard B. Morris in 1973 identified the following seven figures as the key Founding Fathers: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington[45]

References[edit]

^ Chadwick, Bruce (2007). General and Mrs. Washington: The Untold Story of a Marriage and a Revolution. Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 331. ISBN 9781402274954. Retrieved February 17, 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Dunbar, Erica Armstrong (February 16, 2015). "George Washington, Slave Catcher". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

^ Hirschfeld, Fritz (1997). George Washington and Slavery. University of Missouri Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8262-1135-4.

^ Conroy, Sarah Booth (1998). "The Founding Father and His Slaves". Washington Papers. University of Virginia. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

^ "Martha Washington & Slavery". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

^ Number of slaves: Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America, p. 46; Ellis, pp. 262–63. Quotes from visitors to Mount Vernon: Ferling, p. 476.

^ abc Sheerin, Jude (August 18, 2017). "Should Washington and Jefferson monuments come down?". BBC.com. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

^ Ferling 2009, p. 66.

^ Twohig 1994.

^ Slave raffle linked to Washington's reassessment of slavery: Wiencek, pp. 135–36, 178–88

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/#_edn7

^ Fitzpatrick, John C. The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources in Thirty-nine Volumes. 1940 (United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC), Vol. 2, pg. 437.

^ Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life(2010).New York: Penguin Press.

ISBN 978-1-59420-266-7. p.441

^ Slave raffle linked to Washington's reassessment of slavery: Wiencek, pp. 135–36, 178–88. Washington's decision to stop selling slaves: Fritz Hirschfeld, George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal, p. 16. Influence of war and Wheatley: Wiencek, ch 6. Dilemma of selling slaves: Wiencek, p. 230; Ellis, pp. 164–7; Hirschfeld, pp. 27–29.

^ Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), p. 159.

^ Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. p. 278.

^ Virginia reports: Jefferson--33 Grattan, 1730-1880, Thomas Johnson Michie, Thomas Jefferson, Peachy Ridgway Grattan, The Michie Co., 1904, pp. 241-242.

^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 81

^ Kolchin (1993), American Slavery, p. 81

^ Quotes and Lafayette plans: Dorothy Twohig, "'That Species of Property': Washington's Role in the Controversy over Slavery" in George Washington Reconsidered, pp. 121–22.

^ abcd Feagin 2001, p. 54.

^ Fessenden, Marissa (June 9, 2015). "How George Washington Did His Hair". Smithsonian. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

^ Edward G. Lengel (2012). A Companion to George Washington. John Wiley. p. 90. ISBN 9781118219928.

^ Fritz Hirschfeld (1997). George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal. University of Missouri Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780826211354.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ Fitzgerald, Writings, Vol. 29, pp. 56, 154.

^ Robert V. Remini (2007). The House: The History of the House of Representatives. HarperCollins. p. 30. ISBN 9780061341113.

^ Schultz, Jeffrey D. (2002). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans. p. 284. ISBN 9781573561488. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

^ Marcus Pohlmann; Linda Whisenhunt (2002). Student's guide to landmark congressional laws on civil rights. CT: Greenwood. p. 23. ISBN 0-313-31385-7. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

^ "Regulating the Trade". New York Public Library. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

^ Alfred Hunt, Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America, p. 31

^ Dunbar, Erica Armstrong (2015-02-16). "Opinion | George Washington, Slave Catcher". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

^ Schuessler, Jennifer (2017-02-06). "In Search of the Slave Who Defied George Washington". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

^ Holley, Peter (July 27, 2016). "The ugly truth about the White House and its history of slavery". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ Ford, Worthington. The Writings of George Washington (Putnam’s Sons, New York), Vol. 2, pg. 211.

^ Ford, True Washington, pp. 144-7.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ Fitzpatrick, Writings, Vol. 36, p. 70.

^ Ed Lawler, Jr., "Slavery in the President's House", President's House in Philadelphia website, US History.org, 2001–2010, accessed 16 February 2012

^ Striner, Richard (2006). Father Abraham: Lincoln's Relentless Struggle to End Slavery. Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-518306-1.

^ Striner, p. 15.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ "The President's House in Philadelphia", website

^ Richard B. Morris, Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

^ Roger G. Kennedy, Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character (2000), p. 92

^ Crippen II, Alan R. (2005). "John Jay: An American Wilberforce?". John Jay Institute. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2006.I have three male and three female slaves[....] I purchase slaves and manumit them at proper ages and when their faithful services shall have afforded a reasonable retribution.

^ Washington, George. "George Washington's Last Will and Testament, 9 July 1799". Founders Online. National Historical Publications & Records Commission. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

^ Erik S. Root (2008). All Honor to Jefferson?: The Virginia Slavery Debates and the Positive Good Thesis. Lexington Books. p. 19. ISBN 9780739122181.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ Henriques, Peter R. Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington (2006: University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia), p. 146.

^ http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/george-washington-slavery/

^ Twohig, "That Species of Property", pp. 127–28.

^ Harry Washington, Black Loyalist, University of Sidney (Australia).

^ "Exhibit: Slavery in New York - 7 October 2005 to 26 March 2006". New York Historical Society. 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

^ ab "Slavery in the President's House", President's House in Philadelphia website, US History.org, 2001-2010, accessed 16 February 2012

^ Mary V. Thompson, “William Lee & Oney Judge: A Look at George Washington & Slavery,” Journal of the American Revolution, JUNE 19, 2014 (“Billy [Lee] was well-enough known that people who came to Mount Vernon looked forward to meeting him.”) (https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/06/william-lee-and-oney-judge-a-look-at-george-washington-slavery/).

Sources[edit]

Feagin, Joe R. (2001). Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92532-0.

Categories:

- American slave owners

- George Washington

- History of slavery in Virginia

- Slavery in the United States

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.516","walltime":"0.654","ppvisitednodes":{"value":2172,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":112283,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":1971,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":13,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":3,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":83672,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":1,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 483.578 1 -total"," 58.86% 284.636 2 Template:Reflist"," 22.98% 111.132 10 Template:Cite_book"," 9.87% 47.720 5 Template:Cite_news"," 9.28% 44.879 1 Template:Citation_needed"," 8.51% 41.143 1 Template:Fix"," 8.01% 38.727 1 Template:ISBN"," 6.87% 33.216 6 Template:Cite_web"," 6.59% 31.869 1 Template:George_Washington"," 6.03% 29.183 2 Template:Category_handler"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.218","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":5657113,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1270","timestamp":"20190325000538","ttl":2592000,"transientcontent":false}}});});{"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"George Washington and slavery","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington_and_slavery","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q5546058","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q5546058","author":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png"}},"datePublished":"2006-09-03T06:17:41Z","dateModified":"2019-03-12T01:57:05Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3b/GW-painting.jpg"}(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":804,"wgHostname":"mw1270"});});