Sultan Ahmed Mosque

| Sultan Ahmed Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′19″N 28°58′37″E / 41.0053851°N 28.9768247°E / 41.0053851; 28.9768247Coordinates: 41°00′19″N 28°58′37″E / 41.0053851°N 28.9768247°E / 41.0053851; 28.9768247 |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Website | Official website |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Sedefkâr Mehmed Ağa |

| Architectural type | Mosque |

| Architectural style | Islamic, Late Classical Ottoman |

| Completed | 1616 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 10,000 |

| Length | 73 m (240 ft) |

| Width | 65 m (213 ft) |

| Dome height (outer) | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 23.50 m (77.1 ft)[1] |

Minaret(s) | 6 |

| Minaret height | 64 m (210 ft) |

| Materials | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Turkish: Sultan Ahmet Camii) is a historic mosque located in Istanbul, Turkey. A popular tourist site, the Sultan Ahmed Mosque continues to function as a mosque today; men still kneel in prayer on the mosque's lush red carpet after the call to prayer. The Blue Mosque, as it is popularly known, was constructed between 1609 and 1616 during the rule of Ahmed I. Its Külliye contains Ahmed's tomb, a madrasah and a hospice. Hand-painted blue tiles adorn the mosque’s interior walls, and at night the mosque is bathed in blue as lights frame the mosque’s five main domes, six minarets and eight secondary domes.[2] It sits next to the Hagia Sophia, another popular tourist site.

Contents

1 History

2 Architecture

2.1 Interior

2.2 Exterior

2.3 Minarets

3 Pope Benedict XVI's visit and silent meditation

4 Gallery

5 See also

6 Notes

7 Sources

8 Further reading

9 External links

History

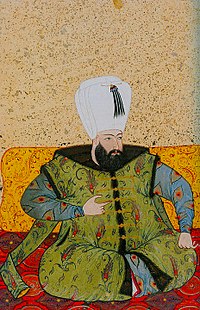

Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque) was constructed by Sedefkar Mehmed Agha on the orders of Sultan Ahmed I.

After the Peace of Zsitvatorok and the crushing loss in the 1603–18 war with Persia, Sultan Ahmet I, decided to build a large mosque in Istanbul to reassert Ottoman power. It would be the first imperial mosque for more than forty years. While his predecessors had paid for their mosques with the spoils of war, Ahmet I procured funds from the Treasury, because he had not gained remarkable victories. The construction was started in 1609 and not completed until 1617.[3]

It caused the anger of the ulama, the Muslim jurists. The mosque was built on the site of the palace of the Byzantine emperors, in front of the basilica Hagia Sophia (at that time, the primary imperial mosque in Istanbul) and the hippodrome, a site of significant symbolic meaning as it dominated the city skyline from the south. Big parts of the south shore of the mosque rest on the foundations, the vaults of the old Grand Palace.[4]

Architecture

Plan and perspective view

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque has five main domes, six minarets, and eight secondary domes. The design is the culmination of two centuries of Ottoman mosque development. It incorporates some Byzantine Christian elements of the neighboring Hagia Sophia with traditional Islamic architecture and is considered to be the last great mosque of the classical period. The architect, Sedefkâr Mehmed Ağa, synthesized the ideas of his master Sinan, aiming for overwhelming size, majesty and splendour. It has a forecourt and special area for ablution. In the middle it has a big fountain. On the upper side it has a big chain. The upper area is made up of 20000 ceramic tiles each having 60 tulip designs. In the lower area it has 200 stained glass windows. [5]

Interior

Interior view, featuring the prayer area and the main dome.

At its lower levels and at every pier, the interior of the mosque is lined with more than 20,000 handmade İznik style ceramic tiles, made at İznik (the ancient Nicaea) in more than fifty different tulip designs. The tiles at lower levels are traditional in design, while at gallery level their design becomes flamboyant with representations of flowers, fruit and cypresses. The tiles were made under the supervision of the Iznik master. The price to be paid for each tile was fixed by the sultan's decree, while tile prices in general increased over time. As a result, the quality of the tiles used in the building decreased gradually.[6]

The upper levels of the interior are dominated by blue paint. More than 200 stained glass windows with intricate designs admit natural light, today assisted by chandeliers. On the chandeliers, ostrich eggs are found that were meant to avoid cobwebs inside the mosque by repelling spiders.[7] The decorations include verses from the Qur'an, many of them made by Seyyid Kasim Gubari, regarded as the greatest calligrapher of his time. The floors are covered with carpets, which are donated by the faithful and are regularly replaced as they wear out. The many spacious windows confer a spacious impression. The casements at floor level are decorated with opus sectile. Each exedra has five windows, some of which are blind. Each semi-dome has 14 windows and the central dome 28 (four of which are blind). The coloured glass for the windows was a gift of the Signoria of Venice to the sultan.

The most important element in the interior of the mosque is the mihrab, which is made of finely carved and sculptured marble, with a stalactite niche and a double inscriptive panel above it. It is surrounded by many windows. The adjacent walls are sheathed in ceramic tiles. To the right of the mihrab is the richly decorated minber, or pulpit, where the imam stands when he is delivering his sermon at the time of noon prayer on Fridays or on holy days. The mosque has been designed so that even when it is at its most crowded, everyone in the mosque can see and hear the imam.[6]

The royal kiosk is situated at the south-east corner. It comprises a platform, a loggia and two small retiring rooms. It gives access to the royal loge in the south-east upper gallery of the mosque. These retiring rooms became the headquarters of the Grand Vizier during the suppression of the rebellious Janissary Corps in 1826. The royal loge (hünkâr mahfil) is supported by ten marble columns. It has its own mihrab, which used to be decorated with a jade rose and gilt[8] and with one hundred Qurans on an inlaid and gilded lecterns.[9]

The many lamps inside the mosque were once covered with gold and gems.[10] Among the glass bowls one could find ostrich eggs and crystal balls.[11] All these decorations have been removed or pillaged for museums.

The great tablets on the walls are inscribed with the names of the caliphs and verses from the Quran. They were originally by the great 17th-century calligrapher Seyyid Kasim Gubari of Diyarbakır but have been repeatedly restored.[6]

It was first announced that the mosque would undertake a series of renovations back in 2016. Numerous renovation works had been completed throughout Istanbul and the restoration of the Blue Mosque was to be the final project. Renovations were expected to take place over three and a half years and be completed by 2020.

Interior view

Exterior

Ablution facilities

The façade of the spacious forecourt was built in the same manner as the façade of the Süleymaniye Mosque, except for the addition of the turrets on the corner domes. The court is about as large as the mosque itself and is surrounded by a continuous vaulted arcade (revak). It has ablution facilities on both sides. The central hexagonal fountain is small relative to the courtyard. The monumental but narrow gateway to the courtyard stands out architecturally from the arcade. Its semi-dome has a fine stalactite structure, crowned by a small ribbed dome on a tall tholobate. Its historical elementary school (Sıbyan Mektebi) is used as "Mosque Information Center" which is adjacent to its outer wall on the side of Hagia Sophia. This is where they provide visitors with a free orientational presentation on the Blue Mosque and Islam in general.[12]

Courtyard of the mosque, at dusk.

A heavy iron chain hangs in the upper part of the court entrance on the western side. Only the sultan was allowed to enter the court of the mosque on horseback. The chain was put there, so that the sultan had to lower his head every single time he entered the court to avoid being hit. This was a symbolic gesture, to ensure the humility of the ruler in the face of the divine.[12]

Minarets

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque is one of the four mosques in Turkey that has six minarets (the other three being the modern Sabancı Mosque in Adana, the Hz. Mikdat Mosque in Mersin and the Green mosque in Arnavutköy). According to folklore, an architect misheard the Sultan's request for "altın minareler" (gold minarets) as "altı minare" (six minarets), at the time a unique feature of the mosque of the Ka'aba in Mecca. When criticized for his presumption, the Sultan then ordered a seventh minaret to be built at the Mecca mosque.[13]

Minarets of the mosque.

Four minarets stand at the corners of the Blue Mosque. Each of these fluted, pencil-shaped minarets has three balconies (Called şerefe) with stalactite corbels, while the two others at the end of the forecourt only have two balconies. Before the muezzin or prayer caller had to climb a narrow spiral staircase five times a day to announce the call to prayer.[13]

Pope Benedict XVI's visit and silent meditation

Pope Benedict XVI visited the Sultan Ahmed Mosque on 30 November 2006 during his visit to Turkey. It was only the second papal visit in history to a Muslim place of worship. Having removed his shoes, the Pope paused for a full two minutes, eyes closed in silent meditation,[14] standing side by side with Mustafa Çağrıcı, the Mufti of Istanbul, and Emrullah Hatipoğlu, the Imam of the Blue Mosque.[15]

The pope “thanked divine Providence for this” and said, “May all believers identify themselves with the one God and bear witness to true brotherhood.” The pontiff noted that Turkey “will be a bridge of friendship and collaboration between East and West”, and he thanked the Turkish people “for the cordiality and sympathy” they showed him throughout his stay, saying, “he felt loved and understood.”[16]

Gallery

Play media

Play media

A short movie showing details of the Blue Mosque

The Blue Mosque at sunset

Seen from Sultanahmet Square, close to the Hagia Sophia

Arcaded forecourt with one of the entrance gates

Prayers inside

Blue tiles

Gateway to the courtyard

View of the inner courtyard

Prayer area

Main dome and its blue tiles

Arcades in the inner courtyard

The blue mosque

The Blue Mosque

One of the minarets of the Blue Mosque

Prayer

See also

- Ottoman architecture

- List of mosques in Istanbul

- Hagia Sophia

- Çamlıca Mosque

- Shah Mosque

Notes

^ Encyclopedia of architectural and engineering feats, Donald Langmead, Christine Garnaut, page 322, 2001

^ "Blue Mosque". sultanahmetcamii.org. Retrieved 12 June 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Goodwin 2003, p. 343.

^ "History". sultanahmetcamii.org. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

^ "Architecture". sultanahmetcamii.org/architecture-of-the-mosque/. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

^ abc "Interior". sultanahmetcamii.org/architecture-of-the-mosque/. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

^ "Sultan Ahmet Cami or Blue Mosque". MuslimHeritage.com. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

^ Öz, T., "Sultan Ahmet Camii' in Vakiflar Dergisi, I, Ankara, 1938

^ Efendi 1834, p. 113.

^ Naima M., Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era; Frazer, London, 1832

^ Tournefort, J.P., Marquis de, Relation d'un voyage du Levant, Amsterdam, 1718

^ ab "Exterior". sultanahmetcamii.org/architecture-of-the-mosque/. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

^ ab "Minarets". sultanahmetcamii.org/architecture-of-the-mosque/. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

^ "Pope Benedict XVI Visits Turkey's Famous Blue Mosque". Fox News. 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2011-10-19.

^ "Pope makes Turkish mosque visit". BBC News. 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

^ "Pope: In mosque I prayed to the one God for all mankind". Asianews.it. 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

Sources

Efendi, Evliya (1834). Narrative of Travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, in the Seventeenth Century. Volume 1. trans. Ritter Joseph Von Hammer. London: Printed for the Oriental translation fund of Great Britain and Ireland.

Goodwin, Godfrey (2003) [1971]. A History of Ottoman Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27429-3.

The Inside Track, On the Go Tours.

Further reading

- Sheila S. Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom – "The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250–1800", Yale University Press, 1994;

ISBN 0-300-05888-8

- Turner, J. (ed.) – Grove Dictionary of Art – Oxford University Press, USA; New edition (January 2, 1996);

ISBN 0-19-517068-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sultan Ahmed Mosque. |

- Website of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, Istanbul

- Photographs by Dick Osseman, PBase