Mashhad

Mashhad مشهد Sanabad & Toos | ||

|---|---|---|

City | ||

From up: Imam Reza Shrine, Nader Shah Tomb, Mashhad Train Station, Hedayat Little Bazzar, Ferdowsi Tomb, Mashhad view at night from Hashemieh | ||

| ||

| Motto(s): City of Paradise (Shahr-e Behesht) | ||

Mashhad Location in Iran | ||

| Coordinates: 36°18′N 59°36′E / 36.300°N 59.600°E / 36.300; 59.600Coordinates: 36°18′N 59°36′E / 36.300°N 59.600°E / 36.300; 59.600 | ||

| Country | ||

| Province | Razavi Khorasan | |

| County | Mashhad | |

| Bakhsh | Central | |

| Mashhad-Sanabad-Toos | 818 AD | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Ghasem Taghizadeh-Khamesi | |

| • City Council | Chairperson Mohammad Reza Heydari | |

| Area [1] | ||

| • City | 351 km2 (136 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 995 m (3,264 ft) | |

| Population (2016 census) | ||

| • Urban | 3,001,184[4] | |

| • Metro | 3,372,660[3] | |

| • Population Rank in Iran | 2nd | |

| Over 25 million pilgrims and tourists per year[2] | ||

| Demonym(s) | Mashhadi, Mashadi, Mashdi (informal) | |

| Time zone | UTC+03:30 (IRST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+04:30 (IRDT) | |

| Climate | BSk | |

| Largest district by area | District 9 (64 km2, land area) | |

| Largest district by population | District 2 (480,000) | |

| Website | www.mashhad.ir | |

Mashhad (Persian: مشهد, Mašhad [mæʃˈhæd] (![]() listen)), also spelled Mashad or Meshad,[5][6][7] is the second most populous city in Iran and the capital of Razavi Khorasan Province. It is located in the northeast of the country, near the borders with Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. It has a population of 3,001,184 inhabitants (2016 census), which includes the areas of Mashhad Taman and Torqabeh.[8] It was a major oasis along the ancient Silk Road connecting with Merv to the east.

listen)), also spelled Mashad or Meshad,[5][6][7] is the second most populous city in Iran and the capital of Razavi Khorasan Province. It is located in the northeast of the country, near the borders with Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. It has a population of 3,001,184 inhabitants (2016 census), which includes the areas of Mashhad Taman and Torqabeh.[8] It was a major oasis along the ancient Silk Road connecting with Merv to the east.

The city is named after the "shrine" of Imam Reza, the eighth Shia Imam. The Imam was buried in a village in Khorasan, which afterwards gained the name Mashhad, meaning the place of martyrdom. Every year, millions of pilgrims visit the Imam Reza shrine. The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid is also buried within the shrine.

Mashhad has been governed by different ethnic groups over the course of its history. The city enjoyed relative prosperity in the Mongol period.

Mashhad is also known colloquially as the city of Ferdowsi, after the Iranian poet who composed the Shahnameh. The city is the hometown of some of the most significant Iranian literary figures and artists, such as the poet Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, the traditional Iranian singer and composer. Ferdowsi and Akhavan Sales are both buried in Tus, an ancient city that is considered to be the main origin of the current city of Mashhad.

On 30 October 2009 (the anniversary of the death of Imam Reza), Iran's then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad declared Mashhad to be "Iran's spiritual capital".[9][10]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Etymology and Early History

1.2 Mongolian invasion: Ilkhanates

1.3 Timurid Empire

1.4 Safavid dynasty

1.5 Afsharid dynasty

1.6 Qajar dynasty

1.7 Pahlavi dynasty

1.7.1 Modernization under Reza Shah

1.7.2 1912 Imam Reza shrine bombardment

1.7.3 1935 Imam Reza shrine rebellion

1.7.4 1941–1979 reforms

1.7.5 1994 Imam Reza shrine bombing

1.8 Mashhad after the Revolution

2 Geography

2.1 Climate

3 Demographics

3.1 Ethnic Groups

3.1.1 Afghan Population

3.2 Religion

4 Economy

4.1 Astan Quds Razavi

4.2 Padideh Shandiz

4.3 Credit Institutions

4.4 Others

5 Language

6 Culture

6.1 Religious Seminaries

6.2 Newspapers

6.3 Capital of Islamic Culture

7 Main sites

8 Transportation

8.1 Airport

8.2 Metro

8.3 Rail

8.4 Road

9 Government and politics

9.1 Members of Parliament

9.2 Members of Assembly of Experts

9.3 City Council and Mayor

10 Universities and Colleges

11 Sports

11.1 Major sport teams

11.2 Other sports

12 Gallery

13 Mashhad as capital of Persia and Independent Khorasan

14 Famous people from Mashhad and Tus

15 Twin towns – sister cities

16 Consulates

16.1 Active

16.2 Former

17 See also

18 Footnotes

19 References

20 External links

History

Etymology and Early History

The name Mashhad comes from Arabic, meaning a martyrium.[11][12] It is also known as the place where Ali ar-Ridha (Persian, Imam Reza), the eighth Imam of Shia Muslims, died (according to the Shias, was martyred). Reza's shrine was placed there.[13]

The ancient Parthian city of Patigrabanâ, mentioned in the Behistun inscription (520 BCE) of the Achaemenid Emperor Darius I, may have been located at the present-day Mashhad.[14]

At the beginning of the 9th century (3rd century AH), Mashhad was a small village called Sanabad, which was situated 24 kilometres (15 miles) away from Tus. There was a summer palace of Humayd ibn Qahtaba, the governor of Khurasan. In 808, when Harun al-Rashid, Abbasid caliph, was passing through to quell the insurrection of Rafi ibn al-Layth in Transoxania, he became ill and died. He was buried under the palace of Humayd ibn Qahtaba. Thus the Dar al-Imarah was known as the Mausoleum of Haruniyyeh. In 818, Ali al-Ridha was martyred by al-Ma'mun and was buried beside the grave of Harun.[15]

Although Mashhad owns the cultural heritage of Tus (including its figures like Nizam al-Mulk, Al-Ghazali, Ahmad Ghazali, Ferdowsi, Asadi Tusi and Shaykh Tusi), earlier Arab geographers have correctly identified Mashhad and Tus as two separate cities that are now located about 19 kilometres (12 miles) from each other.

Mongolian invasion: Ilkhanates

Although some believe that after this event, the city was called Mashhad al-Ridha (the place of martyrdom of al-Ridha), it seems that Mashhad, as a place-name, first appears in al-Maqdisi, i.e., in the last third of the 10th century. About the middle of the 14th century, the traveller Ibn Battuta uses the expression "town of Mashhad al-Rida". Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the name Nuqan, which is still found on coins in the first half of the 14th century under the Il-Khanids, seems to have been gradually replaced by al-Mashhad or Mashhad.

Terken Khatun, Empress of the Khwarazmian Empire, known as "the Queen of the Turks", held captive by Mongol army.

Shias began to make pilgrimages to his grave. By the end of the 9th century, a dome was built above the grave, and many other buildings and bazaars sprang up around it. Over the course of more than a millennium, it has been destroyed and rebuilt several times.[16] In 1161, however, the Ghuzz Turks seized the city, but they spared the sacred area their pillaging.

Mashad al-Ridha was not considered a "great" city until Mongol raids in 1220, which caused the destruction of many large cities in Khurasan but leaving Mashhad relatively intact in the hands of Mongolian commanders because of the cemetery of Ali Al-Rezza and Harun al-Rashid (the latter was stolen).[17]

Thus the survivors of the massacres migrated to Mashhad.[18] When the traveller Ibn Battuta visited the town in 1333, he reported that it was a large town with abundant fruit trees, streams and mills. A great dome of elegant construction surmounts the noble mausoleum, the walls being decorated with colored tiles.[2]

The only well-known food in Mashhad, "sholeh Mashhadi" (شله مشهدی) or "Sholeh", dates back to the era of the Mongolian invasion when it is thought to be cooked with any food available (the main ingredients are meat, grains and abundant spices) and be a Mongolian word.[19][20]

Timurid Empire

The map of the Persian Empire in 1747 at the time of Afsharid Dynasty. The name of Mashhad is seen belong Tous

It seems that the importance of Sanabad-Mashhad continually increased with the growing fame of its sanctuary and the decline of Tus, which received its death blow in 1389 from Miran Shah, a son of Timur. When the Mongol noble who governed the place rebelled and attempted to make himself independent, Miran Shah was sent against him by his father. Tus was stormed after a siege of several months, sacked and left a heap of ruins; 10,000 inhabitants were massacred. Those who escaped the holocaust settled in the shelter of the 'Alid sanctuary. Tus was henceforth abandoned and Mashhad took its place as the capital of the district.[citation needed]

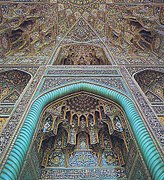

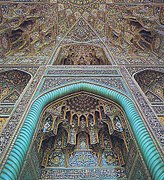

Later on, during the reign of the Timurid Shahrukh Mirza, Mashhad became one of the main cities of the realm. In 1418, his wife Goharshad funded the construction of an outstanding mosque beside the shrine, which is known as the Goharshad Mosque.[18] The mosque remains relatively intact to this date, its great size an indicator to the status the city held in the 15th century.

Safavid dynasty

Shah Ismail I, founder of the Safavid dynasty, conquered Mashhad after the death of Husayn Bayqarah and the decline of the Timurid dynasty. He was later captured by the Uzbeks during the reign of Shah Abbas I.

In the 16th century the town suffered considerably from the repeated raids of the Özbegs (Uzbeks). In 1507, it was taken by the troops of the Shaybani or Shabani Khan. After two decades, Shah Tahmasp I succeeded in repelling the enemy from the town again in 1528. But in 1544, the Özbegs again succeeded in entering the town and plundering and murdering there. The year 1589 was a disastrous one for Mashhad. The Shaybanid 'Abd al-Mu'min after a four months' siege forced the town to surrender. Shah Abbas I, who lived in Mashhad from 1585 till his official ascent of the throne in Qazwin in 1587, was not able to retake Mashhad from the Özbegs till 1598. Mashhad was retaken by the Shah Abbas after a long and hard struggle, defeating the Uzbeks in a great battle near Herat as well as managing to drive them beyond the Oxus River.

Shah Abbas I wanted to encourage Iranians to go to Mashhad for pilgrimage. He is said to have walked from Isfahan to Mashhad. During the Safavid era, Mashhad gained even more religious recognition, becoming the most important city of Greater Khorasan, as several madrasah and other structures were built besides the Imam Reza shrine. Besides its religious significance, Mashhad has played an important political role as well.

The Safavid dynasty has been criticized in a book (Red Shi'sm vs. Black Shi'ism) on the perceived dual aspects of the Shi'a religion throughout history) as a period in which although the dynasty didn't form the idea of Black Shi'ism, but this idea was formed after the defeat of Shah Ismail against the Ottoman leader Sultan Yavuz Selim. Black Shi'ism is a product of the post-Safavid period.

In 1722 under Tahmasp II, the Abdalis Afghans invaded Khorasan and seized Mashhad. After three years, Persians besieged them for two months and retook the city in 1726.

Afsharid dynasty

Mashad saw its greatest glory under Nader Shah, ruler of Iran from 1736 to 1747 and also a great benefactor of the shrine of Imam Reza, who made the city his capital.

Nearly the whole eastern part of the kingdom of Nadir Shah passed to foreign rulers in this period of Persian impotence under the rule of the vigorous Afghan Ahmad Shah Durrani . Ahmad defeated the Persians and took Mashhad after an eight-month siege in 1753. Ahmad Shah and his successor Timur Shah left Shah Rukh in possession of Khurasan as their vassal, making Khurasan a kind of buffer state between them and Persia. As the city's real rulers, however, both these Afghan rulers struck coins in Mashhad. Otherwise, the reign of the blind Shah Rukh, which with repeated short interruptions lasted for nearly half a century, passed without any events of special note. It was only after the death of Timur Shah (1792) that Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, succeeded in taking Shah Rukh's domains and putting him to death in 1795, thus ending the separation of Khurasan from the rest of Persia.

Qajar dynasty

Mashhad in 1858

Some believe that Mashhad was ruled by Shahrukh Afshar and remained the capital of the Afsharid dynasty during Zand dynasty[21] until Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar conquered the then larger region of Khorasan in 1796.[22]

Pahlavi dynasty

Modernization under Reza Shah

The modern development of the city accelerated under the regime of Reza Shah (1925-1941). Shah Reza Hospital (currently Imam Reza Hospital, affiliated with the Basij organization) was founded in 1934; the sugar factory of Abkuh in 1935; and the Faculty of Medicine of Mashhad in 1939. The city's first power station was installed in 1936, and in 1939, the first urban transport service began with two buses. In this year the first population census was performed, with a result of 76,471 inhabitants.[23]

1912 Imam Reza shrine bombardment

In 1911 Yusuf Khan of Herat was declared independent in Mashhad as Muhammad Ali Shah and brought together a large group of reactionaries opposed to the revolution, and keep stirring for some time. This gave Russia the excuse to intervene and 29 March 1912 bombed the city; this bombing killed several people and pilgrims; action against a Muslim shrine caused a great shock to all Islamic countries. On March 29, 1912, the sanctuary of Imam Reza was bombed by the Russian artillery fire, causing some damage, including to the golden dome, resulting in a widespread and persisting resentment in the Shiite Muslim world as well as British India. This bombing was orchestrated by Prince Dabizha (a Georgian who was the Russian Consul in Mashhad) and General Radko (a Bulgarian who was commander of the Russian Cossacks in the city).[24] Yusuf Khan ended captured by the Persians and executed.

1935 Imam Reza shrine rebellion

In 1935, a backlash against the modernizing, anti-religious policies of Reza Shah erupted in the Mashhad shrine. Responding to a cleric who denounced the Shah's heretical innovations, corruption and heavy consumer taxes, many bazaaris and villagers took refuge in the shrine, chanted slogans such as "The Shah is a new Yazid." For four days local police and army refused to violate the shrine and the standoff was ended when troops from Azerbaijan arrived and broke into the shrine,[25] killing dozens and injuring hundreds, and marking a final rupture between Shi'ite clergy and the Shah.[26] According to some Mashhadi historians, the Goharshad Mosque uprising, which took place in 1935, is an uprising against Reza Shah's decree banning all veils (headscarf and chador) on 8 January 1936.[citation needed]

1941–1979 reforms

Comprehensive planning of Mashhad in 1974

Mashhad experienced population growth after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941 because of relative insecurity in rural areas, the 1948 drought, and the establishment of Mashhad University in 1949. At the same time, public transport vehicles increased to 77 buses and 200 taxis and the railway link with the capital Tehran was established in 1957. The 1956 census reflected a population of 241,989 people. The increase in population continued in the following years thanks to the increase in Iranian oil revenues, the decline of the feudal social model, the agrarian reform of 1963, the founding of the city's airport, the creation of new factories and the development of the health system. In 1966, the population reached 409,616 inhabitants, and 667,770 in 1976 . The extension of the city was expanded from 16 to 33 square kilometres (170,000,000 to 360,000,000 square feet).

In 1965 an important urban renewal development project for the surroundings of the shrine of Imam Reza was proposed by the famous Iranian architect and urban designer Dariush Borbor to replace the dilapidated slum conditions which surrounded the historic monuments. The project was officially approved in 1968. In 1977 the surrounding areas were demolished to make way for the implementation of this project. In order to relocate the demolished businesses, a new bazaar was designed and constructed in Meydan-e Ab square (in Persian, میدان آب")[23] by Dariush Borbor. After the revolution the urban renewal project was abandoned.

1994 Imam Reza shrine bombing

On June 20, 1994, a bomb exploded in a prayer hall of the shrine of the Imam Reza[27] The bomb that killed at least 25 people on June 20 in Mashhad exploded on Ashura.[28] The Baluch terrorist, Ramzi Yousef, a Sunni Muslim turned Wahhabi, one of the main perpetrators of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, was found to be behind the plot.[29] However, official state media blamed Mehdi Nahvi, a supposed member of the People's Mujahedin of Iran (MKO), a fundamentally Marxist organization, in order to prevent sectarian violence.

Mashhad after the Revolution

In 1998 and 2003 there were student disturbances after the same events in Tehran.

Geography

The city is located at 36.20º North latitude and 59.35º East longitude, in the valley of the Kashafrud River near Turkmenistan, between the two mountain ranges of Binalood and Hezar Masjed Mountains. The city benefits from the proximity of the mountains, having cool winters, pleasant springs, mild summers, and beautiful autumns. It is only about 250 km (160 mi) from Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.

The city is the administrative center of Mashhad County (or the Shahrestan of Mashhad) as well as the somewhat smaller district (Bakhsh) of Mashhad. The city itself, excluding parts of the surrounding Bakhsh and Shahrestan, is divided into 13 smaller administrative units, with a total population of more than 3 million.[30]

Climate

Mashhad features a steppe climate (Köppen BSk) with hot summers and cool winters. The city only sees about 250 millimetres (9.8 inches) of precipitation per year, some of which occasionally falls in the form of snow. Mashhad also has wetter and drier periods with the bulk of the annual precipitation falling between the months of December and May. Summers are typically hot and dry, with high temperatures sometimes exceeding 35 °C (95 °F). Winters are typically cool to cold and somewhat damper, with overnight lows routinely dropping below freezing. Mashhad enjoys on average just above 2900 hours of sunshine per year.

| Climate data for Mashhad (1951–2010, extremes 1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) | 26.0 (78.8) | 32.0 (89.6) | 35.4 (95.7) | 39.2 (102.6) | 41.6 (106.9) | 43.8 (110.8) | 42.4 (108.3) | 42.0 (107.6) | 35.8 (96.4) | 29.4 (84.9) | 28.2 (82.8) | 43.8 (110.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) | 9.3 (48.7) | 14.2 (57.6) | 20.9 (69.6) | 26.8 (80.2) | 32.3 (90.1) | 34.4 (93.9) | 33.1 (91.6) | 28.9 (84.0) | 22.5 (72.5) | 15.5 (59.9) | 9.8 (49.6) | 21.2 (70.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) | 3.7 (38.7) | 8.5 (47.3) | 14.7 (58.5) | 19.6 (67.3) | 24.4 (75.9) | 26.6 (79.9) | 24.8 (76.6) | 20.3 (68.5) | 14.5 (58.1) | 8.7 (47.7) | 4.0 (39.2) | 14.3 (57.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) | −1.8 (28.8) | 2.9 (37.2) | 8.4 (47.1) | 12.4 (54.3) | 16.4 (61.5) | 18.7 (65.7) | 16.5 (61.7) | 11.7 (53.1) | 6.4 (43.5) | 1.9 (35.4) | −1.7 (28.9) | 7.3 (45.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.0 (−16.6) | −28.0 (−18.4) | −13.0 (8.6) | −7.0 (19.4) | −1.0 (30.2) | 4.0 (39.2) | 10.0 (50.0) | 5.0 (41.0) | −1.0 (30.2) | −8.0 (17.6) | −16.0 (3.2) | −25.0 (−13.0) | −28.0 (−18.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 32.6 (1.28) | 34.5 (1.36) | 55.5 (2.19) | 45.4 (1.79) | 27.2 (1.07) | 4.0 (0.16) | 1.1 (0.04) | 0.7 (0.03) | 2.1 (0.08) | 8.0 (0.31) | 16.1 (0.63) | 24.3 (0.96) | 251.5 (9.90) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.6 | 5.8 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 41.6 |

| Average snowy days | 5.6 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 20.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 73 | 69 | 62 | 50 | 37 | 34 | 33 | 37 | 49 | 63 | 73 | 54 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.3 | 147.5 | 163.3 | 200.4 | 280.4 | 343.2 | 366.9 | 359.7 | 305.2 | 249.5 | 188.3 | 151.6 | 2,904.3 |

| Source: Iran Meteorological Organization (records),[31] (temperatures),[32] (precipitation),[33] (humidity),[34] (days with precipitation),[35] [36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

There are also over 20 million pilgrims who visit the city every year.[2]

Ethnic Groups

The vast majority of Mashhadi people are ethnic Persians, who form the majority of the city's population. Other ethnic groups include Kurdish and Turkmen people who have emigrated recently to the city from the North Khorasan province. There is also a significant community of non-Arabic speakers of Arabian descent who have retained a distinct Arabian culture, cuisine and religious practices. The people from Mashhad who look East Asian are Iranians of Hazara, Turkmen, or Uyghur ancestry or indeed a combination of all other ethnic groups, including Persians, as racial mixing has been widely practiced in this region. Among the non-Iranians, there are many immigrants from Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan.

Afghan Population

As neighbouring areas with cultural ties,[38] there has been a long history of population movements between Khorasan and Afghanistan.[39] Like the other areas in Khorasan province where there is an Afghan community due to the influx of Afghan refugees coming from Afghanistan in recent years, the demographic explosion of Mashhad continued with the addition of some 296 000 Afghans Refugees to Mashhad, following the communist revolution of 1978. In many cases, they are no longer refugees but should be mentioned as locals (Iran's Ministry of Interior estimates that the total number of Afghans in Iran is now around 3 million.[40][41] Considering that there were 296000 Afghans Refugees to Mashhad (from 2.5 million in the whole Iran) following the communist revolution of 1978, the number of Afghans in Mashhad cannot be lesser that 296000 people - and so a rate more than 10.8% should be considered). Afghan refugees originate up to 90% from the provinces of Herat, Farah and Nimruz Province, speak in Dari Farsi and familiar with the culture in Mashhad.

Even before the political frontier between Iran and Afghanistan, the Persian-speaking inhabitants from the provinces of Herat and Farah in Afghanistan had had kinship, as well as ethnical, religious, or economic relations with the Iranian province of Khorasan (especially Mashhad, where people speak a dialect akin with Harat dialect). According to Khorasan Razavi's General Administration of Nationals and Immigrants, there are 142,000 registered Afghan citizens living in Khorasan, 95 percent of which were identified in Mashhad.[42] The Afghan immigrants have several neighborhoods around the city, especially in a new quarter to the northeast of Mashhad. One of the districts inhabited by Afghan immigrants is Golshahr.

Religion

Today, the holy shrine and its museum hold one of the most extensive cultural and artistic treasuries of Iran, in particular manuscript books and paintings. Several important theological schools are associated with the shrine of the Eighth Imam.

The second-largest holy city in the world, Mashhad attracts more than 20 million tourists and pilgrims every year, many of whom come to pay homage to the Imam Reza shrine (the eighth Shi'ite Imam). It has been a magnet for travellers since medieval times.[2] Thus, even as those who complete the pilgrimage to Mecca receive the title of Haji, those who make the pilgrimage to Mashhad—and especially to the Imam Reza shrine—are known as Mashtee, a term employed also of its inhabitants.

As an important problem, the duration when new passengers stay in Mashhad has been considerably reduced to 2 days nowadays and they prefer to finish their trip immediately after doing pilgrimage and shopping in the markets.[43] There are about 3000-5000 unauthorized residential units in Mashhad,[44] which, as a unique statistic worldwide, has caused various problems in the city.[citation needed]

Although mainly inhabited by Muslims, there were in the past some religious minorities in Mashhad, mainly Jews who were forcibly converted to Islam in 1839 after the Allahdad incident took place for Mashhadi Jews in 1839.[45] They became known as Jadid al-Islam ("Newcomers in Islam"). On the outside, they adapted to the Islamic way of life, but often secretly kept their faith and traditions.

Economy

Turquoise, one of the products of Mashhad

Mashhad is Iran's second largest automobile production hub. The city's economy is based mainly on dry fruits, salted nuts, saffron, Iranian sweets like gaz and sohaan, precious stones like agates, turquoise, intricately designed silver jewelry studded with rubies and emeralds, eighteen carat gold jewelry, perfumes, religious souvenirs, trench coats, scarves, termeh, carpets, and rugs.

According to the writings and documents, the oldest existing carpet attributed to the city belongs to the reign of Shah Abbas (Abbas I of Persia). Also, there is a type of carpet, classified as Mashhad Turkbâf, which, as its name suggests, is woven by hand with Turkish knots by craftsmen who emigrated from Tabriz to Mashhad in the nineteenth century.

Among other major industries in the city are the nutrition industries, clothing, leather, textiles, chemicals, steel and non-metallic mineral industries, construction materials factories, thehandicraft industry, and the metal industries.

With more than 55% of all the hotels in Iran, Mashhad is the hub of tourism in the country. Religious shrines are the most powerful attractions for foreign travelers; every year, 20 to 30 million pilgrims from Iran and more than 2 million pilgrims and tourists from elsewhere around the world come to Mashhad.[46]

Mashhad is one of the main producers of leather products in the region.

Unemployment, poverty, drug addiction, theft, and sexual exploitation are the most important social problems of the city.[47]

The divorce rate in Mashhad had increased by 35 percent by 2014.[48][49] Khorasan and Mashhad ranked the second in violence across the country in 2013.[50]

Astan Quds Razavi

AQR Imam Reza Stadium

At the same time, the city has kept its character as a goal of pilgrimage, dominated by the strength of the economic and political authority of the Astan Quds Razavi, the administration of the Shrine waqf, probably the most important in the Muslim world[citation needed]and the largest active bonyad in Iran.[51]

The Astan Quds Razavi is a major player in the economy of the city of Mashhad.[52] The land occupied by the shrine has grown fourfold since 1979 according to the head of the foundation's international relations department. The Shrine of Imam Reza is vaster than Vatican City.[51]

The foundation owns most of the real estate in Mashhad and rents out shop space to bazaaris and hoteliers.[52] The main resource of the institution is endowments, estimated to have annual revenue of $210 billion.[53]Ebrahim Raisi is the current Custodian of Astan Quds Razavi.[2]

Mall at Mashhad

Padideh Shandiz

Mashhad Carpet

Padideh Shandiz International Tourism Development Company, an Iranian private joint-stock holding company, behaves like a public company by selling stocks despite being a joint-stock in the field of restaurants, tourism and construction,[citation needed] with a football club (Padideh F.C.; formerly named Azadegan League club Mes Sarcheshmeh). In January 2015, the company was accused of a "fraud" worth $34.3 billion, which is one eighth of Iran budget.[54]

Credit Institutions

Several credit institutions have been established in Mashhad, including Samenolhojaj (مؤسسه مالی و اعتباری ثامن الحجج), Samenola'emmeh (مؤسسه اعتباری ثامن) and Melal (formerly Askariye, مؤسسه اعتباری عسکریه). The depositors of the first institution have faced problem in receiving cash from the institution.[55][56][57]

Others

The city's International Exhibition Center is the second most active exhibition center after Tehran, which due to proximity to Central Asian countries hosts dozens of international exhibitions each year.

Companies such as Smart-innovators in Mashhad are pioneers in electrical and computer technology.[citation needed]

Language

The language mainly spoken in Mashhad is Persian with a variating Mashhadi accent, which can at times, prove itself as a sort of dialect. The Mashhadi Persian dialect is somewhat different from the standard Persian dialect in some of its tones and stresses.[58]

For instance, the Mashhadi dialect shares vocabulary and phonology with Dari Persian. Likewise, the dialect of Herati in Western Afghanistan is quite similar to the Persian dialect in Mashhad and is akin to the Persian dialects of Khorasan Province, notably those of Mashhad. Hazaragi is another dialect spoken by Hazara people who live as a diaspora community in Mashhad.[59]

Today, the Mashhadi dialect is rarely spoken by young people of Mashhad, most of them perceive it as a humiliation. This is thought to be related to the non-positive performance of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB).[60]

Culture

Relief in Tous depicting popular stories of Persian mythology, from the book of Shahnameh of Ferdowsi.

Religious Seminaries

Tomb of Ferdowsi in Tous.

Long a center of secular and religious learning, Mashhad has been a center for the Islamic arts and sciences as well as piety and pilgrimage. Mashhad was an educational centre, with a considerable number of Islamic schools (madrasas, the majority of them, however, dating from the later afavid period.[citation needed]Mashhad Hawza (Persian: حوزه علمیه مشهد) is one of the largest seminaries of traditional Islamic school of higher learning in Mashhad, which was headed by Abbas Vaez-Tabasi (who was Chairman of the Astan Quds Razavi board from 1979) after the revolution and in which Iranian politician and clerics such as Ali Khamenei, Ahmad Alamolhoda, Abolghasem Khazali, Mohammad Reyshahri, Morteza Motahhari, Abbas Vaez-Tabasi, Madmoud Halabi (the founder of Hojjatieh and Mohammad Hadi Abd-e Khodaee learned Islamic studies.

The number of seminary schools in Mashhad is now thirty nine and there are an estimated 2300 seminarians in the city.[61]

The Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, named after the great Iranian poet, is located here and is regarded as the third institution in attracting foreign students, mainly from Afghanistan, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain, Central Asian republics.

The Madrassa of Ayatollah Al-Khoei, originally built in the seventeenth century and recently replaced with modern facilities, is the city's foremost traditional centre for religious learning. The Razavi University of Islamic Sciences, founded in 1984, stands at the centre of town, within the shrine complex. The prestige of traditional religious education at Mashhad attracts students, known as Talabeh, or "Mollah" internationally.

Tomb of Nader Shah

Mashhad is also home to one of the oldest libraries of the Middle-East called the Central Library of Astan Quds Razavi with a history of over six centuries. There are some six million historical documents in the foundation's central library. A museum is also home to over 70,000 rare manuscripts from various historical eras

The Astan Quds Razavi Central Museum, which is part of the Astan-e Quds Razavi Complex, contains Islamic art and historical artifacts. In 1976, a new edifice was designed and constructed by the well-known Iranian architect Dariush Borbor to house the museum and the ancient manuscripts.

In 1569 (977 H), 'Imad al-Din Mas'ud Shirazi, a physician at the Mashhad hospital, wrote the earliest Islamic treatise on syphilis, one influenced by European medical thought. Kashmar rug is a type of Persian rug indigenous to this region.

Mashhad active galleries include: Mirak Gallery, Parse Gallery, Rezvan Gallery, Soroush Gallery, and the Narvan Gallery.

During the recent years, Mashhad has been a clerical base to monitor the affairs and decisions of state. In 2015, Mashhad's clerics publicly criticized the performance of concert in Mashhad, which led to the order of cancellation of concerts in the city by Ali Jannati, the minister of culture, and then his resignation on 19 October 2016.

Newspapers

There are two influential newspapers in Mashhad, Khorasan (خراسان)and Qods (قدس), which have been considered "conservative newspapers"

They are two Mashhad-based daily published by and representing the views of their current and old owners: Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs and Astan Quds Razavi, respectively.[62]

Capital of Islamic Culture

The Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization named Mashhad 2017's "cultural capital of the Muslim world" in Asia on 24 January 2017.[63]

Main sites

Khayam Street

Apart from Imam Reza shrine, there are a number of large parks, the tombs of historical celebrities in nearby Tus and Nishapur, the tomb of Nader Shah and Kooh Sangi park. The Koohestan Park-e-Shadi Complex includes a zoo, where many wild animals are kept and which attracts many visitors to Mashhad. It is also home to the Mashhad Airbase (formerly Imam Reza airbase), jointly a military installation housing Mirage aircraft, and a civilian international airport.

Some points of interest lie outside the city: the tomb of Khajeh Morad, along the road to Tehran; the tomb of Khajeh Rabi' located 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) north of the city where there are some inscriptions by the renowned Safavid calligrapher Reza Abbasi; and the tomb of Khajeh Abasalt, a distance of 20 kilometres (12 miles) from Mashhad along the road to Neishabur. (The three were all disciples of Imam Reza).

Among the other sights are the tomb of the poet Ferdowsi in Tus, 24 kilometres (15 miles) distance, and the summer resorts at Torghabeh, Torogh, Akhlamad, Zoshk, and Shandiz.

The Shah Public Bath, built during the Safavid era in 1648, is an outstanding example of the architecture of that period. It was recently restored, and is to be turned into a museum.

Transportation

Cable Intersection at Imam Hossein square

Airport

Mashhad is served by the Mashhad International Airport, which handles domestic flights to Iranian cities and international flights, mostly to neighbouring Arab countries. The airport is the country's second busiest after Tehran Mehrabad Airport and above the famous Tehran's Imam Khomeini International Airport.[64]

It is connected to 57 destinations and has frequent flights to 30 cities within Iran and 27 destinations in the Central Asia, the Middle East, East Asia and Europe.[65]

A man walks inside Mashhad International Airport

The airport has been under a US$45.7 ml vast expansion project which has been finished by opening a new Haj Terminal with 10,000 m area on 24 May 2010 and followed by opening a new international terminal with 30000 m2 area with a new parking building, a new custom storage and cargo terminal, new safety and fire fighting buildings and upgrades to taxiways and equipment. Another USD26.5 ml development project for construction of new hangar for aircraft repair facilities and expansion of the west side of the domestic terminal is underway using a BOT contract with the private sector[citation needed].

Metro

Mashhad Urban Railway Corporation (MURCO) is constructing metro and light rail system for the city of Mashhad which includes four lines with 84.5 kilometres (52.5 miles) length. Mashhad Urban Railway Operation Company(MUROC)[66] is responsible for the operation of the lines. The LRT line has been operational since 21 Feb 2011 with 19.5 kilometres (12.1 miles) length and 22 stations[67] and is connected to Mashhad International Airport from early 2016. Total length of line 1 is 24 kilometers and has 24 stations. the current headway in peak hours is 5 minutes. The second line which is a metro line with 14.5 km length and 13 stations is under construction and is estimated to be finished by the ebnd of 2018.[68] First phase of line 2 with 8 kilometers and 7 station is started since 21 Feb 2017. In 20 March two station were added to the network in test operational mode and the first interchange station was added to the network. In 7 May 2018

Iranian Persident Hassan Rouhani took part in the inauguration ceremony of the first Mashhad Urban Railway interchange station "Shariati" which connects line 1 and 2.[69]

currently line 2 operates from Saturday to Thursday with 10.1 km and 9 stations from 6 AM to 6 PM and the current headway is 15 minutes.[70] Currently Mashhad Urban Railway Operation Company(MUROC)[66] Operates 2 lines with 34.1 kilometers length and 33 station.

Rail

Mashhad is connected to three major rail lines: Tehran-Mashhad, Mashhad-Bafgh (running south), and Mashhad-Sarakhs at the border with Turkmenistan. Some freight trains continue from Sarakhs towards Uzbekistan and to Kazakhstan, but have to change bogies because of the difference in Rail gauge. A rail line is being constructed off the Mashhad-Bafgh line to connect Mashhad to Herat in Afghanistan, but has not yet been completed and one is planned to connect to the Gorgan railhead and the port of Bandar Torkaman on the Caspian Sea to the west. Passenger rail services are provided by Raja Passenger Trains Company[71] and all trains are operated by R.A.I.,[72] Rah-Ahan (Railway) of Iran, the national railway company.

A new service from Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan to Mashad, Iran was launched in December 2016.[73]

Road

Road 95 links Mashhad south to Torbat-e Heydarieh and Birjand. Road 44 goes west towards Shahrud and Tehran. Road 22 travels northwest towards Bojnurd. Ashgabat in Turkmenistan is 220 km away and is accessible via Road 22 (AH78). Herat in Afghanistan is 310 km away and accessible via Road 97 (AH1).

Government and politics

Members of Parliament

Mashhad's current members of parliament are described as politician with fundamentalist conservative tendencies, who are mostly the members of Front of Islamic Revolution Stability, an Iranian principlist political group. They were elected to the Parliament on 26 February 2016.

Members of Assembly of Experts

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi and Ahmad Alamolhoda are two members of the Iranian Assembly of Experts from Mashhad. Hashemi Shahroudi is currently First Vice-Chairman of the Iranian Assembly of Experts.[74] He was the Head of Iran's Judiciary from 1999 until 2009 who upon accepting his position, appointed Saeed Mortazavi, a well known fundamentalist and controversial figure during President Mahmud Ahmadinejad's reelection, prosecutor general of Iran.[75] He was supported by Mashhad's reformists as the candidate of the Fifth Assembly on 26 February 2016.

City Council and Mayor

In 2013, an Iranian principlist political group, Front of Islamic Revolution Stability (which is partly made up of former ministers of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi),[76] gained a landslide victory in Mashhad City Council,[77] which on September 23, 2013, elected Seyed Sowlat Mortazavi as mayor, who was former governor of the province of South Khorasan and the city of Birjand.[78] The municipality's budget amounted to 9600 billion Toman in 2015.[79]

Universities and Colleges

Commemoration Ceremony of Mashhad's foreign graduates

Universities

- Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

- Ferdowsi University of Mashhad - International Campus

- Golbahar University of Science and New Technology

- Imam Reza International University

- Islamic Azad University of Khorasan - Golbahar International Campus

- Islamic Azad University of Mashhad

- Khayyam University

Mashhad University of Medical Sciences at the Wayback Machine (archived 2017-03-24)- Payame Noor University of Mashhad

- Razavi University of Islamic Sciences

Sadjad University of Technology at the Wayback Machine (archived 2010-05-07)- Sama Technical and Vocational Training Center (Islamic Azad University of Mashhad)

- Sport Sciences Research Institute of Iran

Colleges

Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

- Al Mustafa International University

Alzahra Girls Technical and Vocational College of Mashhad (Technical and Vocational University) at the Wayback Machine (archived 2013-06-07)- Arman Razavi Girls Institute of Higher Education

- Asrar Institute of Higher Education

- Attar Institute of Higher Education

- Bahar Institute of Higher Education

- Binalood Institute of Higher Education

- Cultural Heritage, Hand Crafts, and Tourism Higher Education Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Eqbal Lahoori Institute of Higher Education

Ferdows Institute of Higher Education at the Wayback Machine (archived 2015-05-06)- Hakim Toos Institute of Higher Education

- Hekmat Razavi Institute of Higher Education

- Iranian Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research, Mashhad Branch (Jahad Daneshgahi of Mashhad)

- Jahad Keshavarzi Higher Education Center of Khorasan Razavi (Shahid Hashemi Nejad)

- Kavian Institute of Higher Education

- Kharazmi Azad Institute of Higher Education of Khorasan

- Khavaran Institute of Higher Education

- Kheradgarayan Motahar Institute of higher education

- Khorasan Institute of Higher Education

- Khorasan Razavi Judiciary Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Khorasan Razavi Municipalities' Institute of Research, Education, and Consultation of (University of Science and Technology)

- Mashhad Aviation Industry Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Mashhad Aviation Training Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Mashhad Culture and Art Center 1 (University of Science and Technology)

- Mashhad Koran Reciters Society

- Mashhad Prisons Organization Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Mashhad Tax center (University of Science and Technology)

- Navvab Higher Clerical School

- Part Tyre Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Red Crescent Society of Khorasan Razavi (University of Science and Technology)

- Salman Institute of Higher Education

- Samen Teacher Training Center of Mashhad (Farhangian University)

- Samen Training Center of Mashhad (Technical and Vocational University)

- Sanabad Golbahar Institute of Higher Education

- Shahid Beheshti Teacher Training College (Farhangian University)

- Shahid Hashemi Nejad Teacher Training College (Farhangian University)

Shahid Kamyab Teacher Training Center at the Wayback Machine (archived 2012-08-15)

Shahid Montazari Technical Faculty (Technical and Vocational University) at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2015-10-17)- Shandiz Institute of Higher Education

- Khorasan Razavi Taavon Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Tabaran Institute of Higher Education

- Toos Institute of Higher Education

- Toos Porcelain Center (University of Science and Technology)

Varastegan Medical Sciences Institute of Higher Education at the Wayback Machine (archived 2017-03-23)- Khorasan Water and Electricity Industry Center (University of Science and Technology)

- Workers' House; Mashhad Branch (University of Science and Technology)

Sports

Major sport teams

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Padideh F.C. | Iran Pro League | Football | Samen Stadium | 2007 |

FC Mashhad | Iran Pro League | Football | Takhti Stadium | 1970 |

Samen Mashhad BC | Iranian Basketball Super League | Basketball | Shahid Beheshti Sport Complex | 2011 |

Mizan Khorasan VC | Iranian Volleyball Super League | Volleyball | Shahid Beheshti Sport Complex | 2010 |

Farsh Ara Mashhad FSC | Iranian Futsal Super League | Futsal | Shahid Beheshti Sport Complex | 1994 |

Ferdosi Mashhad FSC | Iranian Futsal Super League | Futsal | Shahid Beheshti Sport Complex | 2011 |

Rahahan Khorasan W.C. | Iranian Premier Wrestling League | Freestyle wrestling | Mohammad Ali Sahraei Hall[80] | 1995 |

Other sports

City was host to 2009 Junior World Championships in sitting volleyball where Iran's junior team won Gold.

Gallery

- Some photos of Mashhad (The City of Paradise)

Imam Reza shrine

Proma Hypermarket

Mashhad is the major trade center of saffron in Iran.

Many beautiful handicraft products are sold in Shandiz and Torghabeh.

Some Iranian Handicrafts (metalwork) in Torghabeh

Front façade of the Ferdowsi's mausoleum in Tous

Haruniyeh Dome in Tous

Malek's House in Mashhad

St. Mesrop Armenian church in Mashhad

Tous Museum near Mashhad

Shandiz a tourist town near Mashhad

Homa Hotel, Branch of Homa Hotel Group

Mashhad's countryside

Shashlik, one of the Iranian tasty foods in Mashhad

Pistols from Afsharid Empire era at Naderi Museum

Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

Faculty of Engineering, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

Mashhad Urban Railway

Almas Shargh (East Diamond) Shopping Center

Mashhad Metro (LRT) Station

Mashhad Metro (LRT) network sign

Mashhad Metro Entrance and Urban Design

City Signpost

Imam Hussein Square

Mashhad Firefighter's Parade

Mashhad Firefighter's Parade

Mashhad Firefighter's Parade

A mosque in Mashhad

Goharshad Mosque, Abbasid Ivan in Atiq yard

An old photo of Goharshad Mosque

Lost girl sculpture

Oven of Rastgar Moqaddam

Ferdowsi tomb

Ferdowsi tomb

A Masterpiece in Mashhad metro station

Padideh Shandiz Tourism Center

Shandiz Restaurant, serving traditional Iranian cuisine

Kang countryside

Kang countryside

Mashhad as capital of Persia and Independent Khorasan

The following Shahanshahs had Mashhad as their capital:

- Kianid Dynasty

- Malek Mahmoud Sistani 1722–1726

- Afsharid dynasty

- Nader Shah

- Adil Shah

- Ebrahim Afshar

- Shahrukh Afshar

- Nadir Mirza of Khorasan

- Safavid Dynasty

- Soleyman II

- Autonomous Government of Khorasan

- Colonel Mohammad Taghi Khan Pessyan

Famous people from Mashhad and Tus

Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, Singer-songwriter received the Picasso Award, UNESCO Mozart Medal and National Order of Merit (France)

Mahmoud Khayami, Businessman, philanthropist and Industrialist an Honorary CBE, KSS, GCFO

Manouchehr Eghbal, 65th Prime Minister of Iran

Abdolhossein Teymourtash, politician and statesman, the first Minister of Court of Iran

Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, a Marja and the second and current Supreme Leader of Iran

Jabir ibn Hayyan, was a prominent polymath, a chemist and alchemist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer, geographer, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician

Rafi Pitts, Iranian film director

Ali Shirazinia known as Dubfire, Iranian American house and techno DJ and producer

Anousheh Ansari Iranian-American engineer, co-founder and chairwoman of Prodea Systems, co-founder and CEO of Telecom Technologies, Inc. (TTI), sponsor of the Ansari X Prize

Heshmat Mohajerani, footballer and former football manager

Rasoul Khadem, Wrestling coach

Reza Ghoochannejhad, footballer

- Religious and political figures

Abbas Vaez-Tabasi, 25 June 1935 - 4 March 2016; Grand Imam and Chairman of the Astan Quds Razavi board

Abdolhossein Teymourtash, prominent Iraninan statesman and first minister of justice under the Pahlavis

Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, born 1959 in Shirvan; Interior Minister of President Hassan Rouhani

Abu Muslim Khorasani, c. 700–755; Abu Muslim Abd al-Rahman ibn Muslim al-Khorasani, Abbasid general of Persian origin

Al-Ghazali, 1058–1111; Islamic theologian, jurist, philosopher, cosmologist, psychologist and mystic of Persian origin

Al-Hurr al-Aamili, Shia scholar and muhaddith

Ali al-Sistani, born approximately August 4, 1930; Twelver Shi'a marja residing in Iraq since 1951

Amirteymour Kalali, prominent Iraninan statesman

Goharshad Begum, Persian noble and wife of Shāh Rukh, the emperor of the Timurid Dynasty of Herāt

Hadi Khamenei, b. 1947; mid-ranking cleric who is a member of the reformist Association of Combatant Clerics

Hassan Ghazizadeh Hashemi, born 21 March 1959 in Fariman; Minister of Health and Medical Education of President Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rahimpour Azghadi, Conservative political strategist and popular television personality in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Hossein Vahid Khorasani, born in 1924; Iranian Twelver Shi'a Marja

Manouchehr Eghbal, 14 October 1909 – 25 November 1977, a Prime Minister of Iran

Mohammad-Ali Abtahi, born January 27, 1958; former Vice President of Iran and a close associate of former reformist President Mohammad Khatami

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, born 23 August 1961 in Torghabeh, near Mashhad; the current Mayor of Tehran, Iran

Mohammad-Kazem Khorasani, 1839–1911; Twelver Shi'a Marja, Persian (Iranian) politician, philosopher, reformer

Morteza Motahhari, 31 January 1919 in Fariman - 1 May 1979; an Iranian cleric, philosopher, lecturer, and politician

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, born February 1201 in Tūs, Khorasan – 26 June 1274 in al-Kāżimiyyah near Baghdad; Persian of the Ismaili and subsequently Twelver Shī'ah Islamic belief

Nizam al-Mulk, 1018 – 14 October 1092; celebrated Persian scholar and vizier of the Seljuq Empire

Saeed Jalili, born 1965 in Mashhad; Iranian politician and the present secretary of Iran's Supreme National Security Council

Seyed Hassan Firuzabadi, current major general, Islamic Republic of Iran

Seyyed Ali Khamenei, born 17 July 1939; former president and current supreme leader of Iran

Shahrukh (Timurid dynasty), August 20, 1377 – March 12, 1447; ruler of the eastern portion of the empire established by the Central Asian warlord Timur (Tamerlane)

Shaykh Tusi, 385–460 A.H.; prominent Persian scholar of the Shi'a Twelver Islamic belief

Sheikh Ali Tehrani, brother-in-law of Seyyed Ali Khamenei, currently living in Iran. He is one of the oppositions of current Iranian government.

Timur Shah Durrani, Emir of Afghanistan 1772-1793[citation needed]

- Writers and scientists

Abolfazl Beyhaqi, 995–1077; a Persian historian and author

Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī, 10 June 940 – 1 July 998; Persian mathematician and astronomer

Abū Ja'far al-Khāzin, 900–971; Persian astronomer and mathematician from Khorasan

Abu-Mansur Daqiqi, 935/942–976/980

Abusa'id Abolkhayr, December 7, 967 – January 12, 1049 / Muharram ul Haram 1, 357 – Sha'aban 4, 440 AH; famous Persian Sufi who contributed extensively to the evolution of Sufi tradition

Amir Ghavidel, March 1947 - November 2009; an Iranian director and script writer

Anvari, 1126–1189, one of the greatest Persian poets

Arion Golmakani; an American author of Iranian origin. His award-winning memoir Solacers details his childhood in Mashhad.

Asadi Tusi, born in Tus, Iranian province of Khorasan, died 1072 Tabriz, Iran; Persian poet of Iranian national epics

Ferdowsi, 935–1020 in Tus; a Persian poet

Jābir ibn Hayyān, c. 721 in Tus – c. 815 in Kufa; prominent polymath: a chemist and alchemist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer, geologist, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician

Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, 1928, Mashhad, Iran – 1990, Tehran, Iran; a Persian poet

Mohammad Mokhtari (writer), Iranian writer who was murdered on the outskirts of Tehran in the course of the Chain Murders of Iran.

Mohammad-Taghi Bahar, November 6, 1884, Mashhad, Iran – April 22, 1951; Tehran, Iran

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, 1135–1213; Persian mathematician and astronomer of the Islamic Golden Age (during the Middle Ages)

- Artists

25band, both singers born in Mashhad; Pop Group formed in 2010

Abdi Behravanfar, born June 1975 in Mashhad; an Iranian Singer, guitar player and singer-songwriter

Ali "Dubfire" Shirazinia, born 19 April 1971; musician/dj (co-founder of Deep Dish)

Anoushirvan Arjmand, Iranian actor

Borzoo Arjmand, born 1975 in Mashhad; Iranian Cinema, Theatre, and Television actor

Dariush Arjmand, Iranian actor

Darya Dadvar, born 1971 in Mashhad; an accomplished Iranian soprano soloist and composer

Hamed Behdad, born 17 November 1973 in Mashhad; Iranian actor

Hamid Motebassem, born 1958 in Mashhad; Iranian musician and tar and setar player

Ho3ein Eblis, is considered as one of pioneers of "Persian Rap" along with Hichkas and Reza Pishro

Homayoun Shajarian, Mohammad-Reza Shajarian's son, born 21 May 1975; renowned Persian classical music vocalist, as well as a Tombak and Kamancheh player

Iran Darroudi, born 2 September 1936 in Mashhad; Iranian artist

Javad Jalali, born 30 May 1977 in Mashhad; Iranian Photographer and Cinematographer

Mahdi Bemani Naeini, born 3 November 1968; Iranian film director, cinematographer, TV cameraman and photographer

Marshall Manesh, born 16 August 1950 in Mashhad; Iranian-American actor

Mitra Hajjar, born February 4, 1977; Iranian actress

Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, born 23 September 1940 in Mashhad; internationally and critically acclaimed Persian traditional singer, composer and Master (Ostad) of Persian music

Mohsen Namjoo, born 1976 in Torbat-e-Jaam; Iranian singer-songwriter, author, musician, and setar player

Navid Negahban, born 2 June 1968 in Mashhad; Iranian-American actor

Noureddin Zarrinkelk, born 1937 in Mashhad; renowned Iranian animator, concept artist, editor, graphic designer, illustrator, layout artist, photographer, script writer and sculptor

Ovanes Ohanian, ?–1961 Tehran; Armenian-Iranian filmmaker who established the first film school in Iran

Pouran Jinchi, born 1959 in Mashhad; Iranian-American artist

Rafi Pitts, born 1967 in Mashhad; internationally acclaimed Iranian film director

Reza Attaran, born 31 March 1968 in Mashhad; Iranian actor and director

Reza Kianian, born July 17, 1951 in Mashhad; Iranian actor

Valy Hedjasi]], born June 1986 in Mashhad; Afghan Pop Singer

Zohreh Jooya, born in Mashhad; Iranian-Afghan Classical Singer

- Scientists

Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī, 10 June 940 – 1 July 998; Persian mathematician and astronomer

Anousheh Ansari, born 12 September 1966; the Iranian-American co-founder and chairman of Prodea Systems, Inc and a spaceflight participant with the Russian space program

- Sports figures

Abbas Chamanyan, Iranian football coach, manager, and former player

Abbas Golmakani, World's wrestling champion during the 1950s

Abolfazl Safavi, Iran professional football player for Aboumoslem team in Takhte Jamshid League; He was later executed in prison by the Iranian regime in 1982 for his affiliation with Iranian opposition, the MEK

Ali Baghbanbashi, athlete

Alireza Vahedi Nikbakht, born June 30, 1980 in Mashhad; Iranian professional football player

Amir Ghaseminejad, judoka

Amir Reza Khadem, born February 10, 1970 in Mashhad, wrestler

Amir Tavakkolian, wrestler

Farbod Farman, basketballer

Farhad Zarif, born March 3, 1983, Volleyballer

Ghodrat Bahadori, Iranian Futsaler/Indoor soccer player

Hamed Afagh, basketballer

Hamid Reza Mobarez, swimmer

Hasan Kamranifar, Iranian football referee

Heshmat Mohajerani, born January, 1936 in Mashhad, Iran; Iranian football coach, manager, and former player

Hossein Badamaki, Iranian professional football player

Hossein Ghadam, Iran professional football player for Aboumoslem team

Hossein Sokhandan, Iranian football referee

Hossein Tayyebi, Iranian Futsaler/Indoor soccer player

Javad Mahjoub, judoka

Kamia Yousufi, Afghani female sprinter born in Mashhad to Afghani parents

Khodadad Azizi, born June 22, 1971 in Mashhad, Iran; retired professional football striker

Kia Zolgharnain, Iranian-American former Futsaler/Indoor soccer player

Mahdi Javid, Iranian Futsaler/Indoor soccer player

Majid Khodaei, wrestler

Maryam Sedarati, athlete, Iran record holder in women high jump for three decades

Masoud Haji Akhondzadeh, judoka

Mohammad Khadem, wrestler

Mohammad Mansouri, Iranian professional football player

Mohsen Ghahramani, Iranian football referee

Mohsen Torki, Iranian football referee

Rasoul Khadem, born February 17, 1972 in Mashhad, wrestler

Reza Enayati, Iranian professional football player

Reza Ghoochannejhad, Iranian-Dutch professional football player

Rouzbeh Arghavan, basketballer

- Others

Ali Akbar Fayyaz, a renowned historian of early Islam and literary critic, founder of the School of Letters and Humanities at the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

Hesam Kolahan, World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

Hossein Sabet, Iranian businessman and Persian carpet dealer who owns Sabet International Trading Co.

Mahmoud Khayami, born 1930 in Mashhad, Iran; Iranian born industrialist and philanthropist, of French nationality

Maryam Monsef, Afghan-Canadian Minister of Democratic Institutions, MP for Peterborough-Kawartha.

Twin towns – sister cities

Mashhad is twinned with:

Karachi, Pakistan[81] (May 2012)

Karachi, Pakistan[81] (May 2012)

Lahore, Pakistan[82] (2006)

Lahore, Pakistan[82] (2006)

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia[83] (2006)

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia[83] (2006)

Ürümqi, China[84]

Ürümqi, China[84]

Mazari Sharif, Afghanistan[85]

Mazari Sharif, Afghanistan[85]

Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey

Consulates

Afghan Consul General met with the Mayor of Mashhad

Active

Afghanistan (1921–)

Afghanistan (1921–)

Iraq (2007–)[86]

Iraq (2007–)[86]

Kyrgyzstan (1996–)

Kyrgyzstan (1996–)

Pakistan (1975–)[87]

Pakistan (1975–)[87]

Tajikistan (Embassy Representative Office: 1995–)[88][89][90]

Tajikistan (Embassy Representative Office: 1995–)[88][89][90]

Turkey (1919-?,1930–?, 2014–)[91][92]

Turkey (1919-?,1930–?, 2014–)[91][92]

Turkmenistan (1995–)

Turkmenistan (1995–)

Former

United Kingdom (1889–1975)[93]

United Kingdom (1889–1975)[93]

Russia (1889–1917)

Russia (1889–1917)

Soviet Union (1917–1937,1941–1979)

Soviet Union (1917–1937,1941–1979)

China (1941-?)[94]

China (1941-?)[94]

United States (1949–?)[95]

United States (1949–?)[95]

Poland[96]

Poland[96]

India

India

Japan

Japan

Jordan

Jordan

Lebanon

Lebanon

West Germany (c. 1984)

West Germany (c. 1984)

Kazakhstan (1995–2009)[97]

Kazakhstan (1995–2009)[97]

Saudi Arabia (2004–2016)[98]

Saudi Arabia (2004–2016)[98]

See also

- The National Library of Astan Quds Razavi

- Mashadi Jewish Community

- Sport Sciences Research Institute of Iran

Footnotes

^ "Local Government Profile". United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Retrieved 4 February 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcd "Sacred Sites: Mashhad, Iran". sacredsites.com. Archived from the original on 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2006-03-13.

^ "Major Agglomerations of the World - Population Statistics and Maps". citypopulation.de. 2018-09-13. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13.

^ https://www.amar.org.ir/english

^ "Mashhad". Britannica. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

^ Sharafedin, Bozorgmehr (29 December 2017). "Hundreds protest against high prices in Iran". Reuters. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

^ Dockery, Wesley (3 January 2018). "Iran protests: Arab states between trepidation and glee". DW. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

^ "Razavi Khorasan (Iran): Counties & Cities - Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". www.citypopulation.de.

^ مشهد، پایتخت معنوی ایران اعلام شد [Mashhad, Iran's spiritual capital] (in Persian). Khorasan newspaper. 9 Aban 1388. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved Persian date Khordad 23 1394. Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help)

^ نامگذاري مشهد به عنوان پايتخت معنوي "Nombramiento de Mashhad como capital espiritual de Irán" (in Persian). Shahr.ir. 1 November 2009. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936 p. 127

^ The Shias: A Short Gistory, Heinz Halm, p. 26

^ "Iran travel Information". persiatours.com.

^ "Hystaspes (2) - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

^ Zabeth (1999) pp. 12–13.

^ Zabeth (1999) pp. 13–16.

^ موسوي 1370, p. 40

^ ab Zabeth (1999) pp. 14–15.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2016-12-22.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "زبان و ادبیات ترکان خراسان - غذاهای سنتی گریوان". salariyan.blogfa.com.

^ نوایی، عبدالحسین. کریم خان زند

^ Ghani, Cyrus (6 January 2001). Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power. I.B.Tauris. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86064-629-4. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

^ ab تاریخجه شهر مشهد, "Historia de la ciudad de Mashhad". Portal de la Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Mashhad (in Persian). Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

^ Kazemzadeh, Firuz (10 April 2013). Russia and Britain in Persia: Imperial Ambitions in Qajar Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-85772-173-0.

^ Ervand, History of Modern Iran, (2008), p.94

^ Bakhash, Shaul, Reign of the Ayatollahs : Iran and the Islamic Revolution by Shaul, Bakhash, Basic Books, 1984, p. 22.

^ "ABC Evening News for Monday, Jun 20, 1994". Tvnews.vanderbilt.edu. 1994-06-20. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

^ "Explosive circles: Iran. (Mashhad bombing)". Highbeam.com. 1994-06-25. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

^ "Context of 'Mid-1994: Ramzi Yousef Works Closely with Al-Qaeda Leaders". Historycommons.org. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2008-02-27.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^

"Highest record temperature in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

"Lowest record temperature in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"Average Maximum temperature in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

"Average Mean Daily temperature in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

"Average Minimum temperature in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"Monthly Total Precipitation in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"Average relative humidity in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"No. Of days with precipitation equal to or greater than 1 mm in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"No. Of days with snow in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^

"Monthly total sunshine hours in Mashhad by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

^ Iran Foreign Policy & Government Guide (World Business Law Handbook Library), Usa Ibp, Intl Business Pubn., 2006, p. 149

^ Glazebrook & Abbasi-Shavazi 2007, p. 189

^ Abbas Hajimohammadi and Shaminder Dulai, eds. (6 November 2014). "Photos: The Life of Afghan Refugees in Tehran". Newsweek. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

^ Koepke, Bruce (4 February 2011), "The Situation of Afghans in the Islamic Republic of Iran Nine Years After the Overthrow of the Taliban Regime in Afghanistan", Middle East Institute, retrieved 2014-11-07

^ "مهاجرت افغانها برای همسایه دردسرساز شد/ سرنوشت خاکستری اتباع خارجی در مشهد". خبرگزاری مهر - اخبار ایران و جهان - Mehr News Agency. 1 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ http://news.mashhad.ir/news/47876-ماندگاری-زائران-مشهد-نصف-اقامت-مسافران-یزد-کاشان-کاهش-یافت.html

^ http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13910923000693

^ The double lives of Mashhadi Jews, Jerusalem Post, 12 augustus 2007.

^ correspondent, Tehran Bureau (7 May 2015). "Prayer, food, sex and water parks in Iran's holy city of Mashhad" – via The Guardian.

^ "تور مشهد - نقد و اقساط (شروع از 200,000 تومان)". irandehkadeh.com.

^ "افزایش 35درصدی طلاق در مشهد". پایگاه خبری تحلیلی قاصد نیوز. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ "مسائل جنسی عامل 60 درصد طلاق ها در مشهد است/راه های افزایش کیفیت رابطه جنسی". سلامت نیوز. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ "بعد از اعتیاد و طلاق، خشونت، سومین آسیب عمده اجتماعی در مشهد". پایگاه خبری تحلیلی قاصد نیوز. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ ab Higgins, Andrew (2 June 2007). "Inside Iran's Holy Money Machine". WSJ. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ ab Christopher de Bellaigue, The Struggle for Iran, New York Review of Books, 2007, p.15

^ Iran: Order Out of Chaos Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

^ Kamdar, Nazanin (January 6, 2015). "پدیده شاندیز؛". Rooz Online. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

^ "پیشرفت های جدید در ساماندهی مؤسسات اعتباری/ ثامن الحجج در کدام مرحله دریافت مجوز است؟". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ «مجوز تغییر نام موسسه اعتباری عسکریه به موسسه ملل صادر شد». کانون بانک ها و موسسات خصوصی. بازبینیشده در ۱۳۹۵/۰۴/۱۰.

^ "مردم گول نخورند / موسسات ثامنالحجج و ثامن مجوز ندارند". Jamejam Online. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ "Overlooking dialect associated with forgetting identity: academic". 23 August 2008.

^ Area Handbook for Afghanistan, page 77, Harvey Henry Smith, American University (Washington, D.C.) Foreign Area Studies

^ "روزنامه مردم مشهد ، شهرآرا". shahrara.com.

^ مرکز مدیریت حوزهٔ علمیهٔ خراسان، کارنمای عملکرد سال ۱۳۸۶ مرکز مدیریت حوزهٔ علمیهٔ خراسان، ج ۱، ص ۹–۱۱

^ "Guide to Iranian Media and Broadcast" (PDF). BBC Monitoring. March 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

^ "Mashhad named cultural capital of Muslim world". Press TV. 24 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

^ "Photos: Airplane Overhaul Facility in Mashhad, Eastern Iran". www.payvand.com.

^ Photos: Airplane Overhaul Facility in Mashhad, Eastern Iran Archived 15 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Payvand.com.

^ ab https://metro.mashhad.ir

^

قطار شهري مشهد به صورت آزمايشي به بهرهبرداري رسيد (in Persian). Fars News Agency. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

^

حفاري خط 2 قطارشهري مشهد آغاز شد (in Persian). Fars News Agency. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

^ "اتصال خط یک و دو قطارشهری مشهد با حضور رییس جمهور". MUROC. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

^ "ساعت کاری خط دو قطار شهری مشهد افزایش یافت/خط دو می تواند ۷۰ هزار مسافر جابجا کند". MUROC. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

^ "شرکت حمل و نقل ریلی رجا". raja.ir. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2009-02-23.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2017-01-14.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Seyyed Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi (First vice chairman)". Official website of the Assembly of Experts - Management Committee of [the] Assembly of Experts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

^ ".:Middle East Online::Feared Iranian prosecutor falls from grace:". www.middle-east-online.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-08. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

^ Bozorgmehr, Najmeh (February 23, 2012). "Hardline group emerges as Iran poll threat". Financial Times. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

^ "سهم گروههای سیاسی از چهارمین انتخابات شورای شهر در تهران و ۸ شهر بزرگ". Khabar Online. July 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

^ سید صولت مرتضوی شهردار مشهد شد "Seyed Soulat Mortazaví, alcalde de Mashhad" (in Persian). Khabar Online. Fars News. September 23, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "رسانهها هر جا تخلف دیدند، فریاد بزنند". www.mashhadnews.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

^ "هیات کشتی استان خراسان رضوی". Razavisport.ir. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

^ "Karachi and Mashhad Declared Sister Cities". Daily Times. 2012-05-12.

^ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 2007-03-02. Archived from the original on 2013-09-29. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

^ "Mashhad-Kuala Lumpur Become Sister Cities". Mircea Birca. Eurasia Press and News. 2006-10-14.

^ جم, Jamejam, جام (10 September 2011). مشهد و ارومچي خواهرخوانده شدند. Jamejam Online. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

^ "golbaharnews.com". www.golbaharnews.com.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2012-07-27.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-03-18. Retrieved 2012-07-27.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "دفتر سفارت جمهوری تاجیکستان در مشهد". www.tajik-em-mashhad.ir.

^ User, Super. "CONTACTS - Tajik Embassy in Iran". www.tajembiran.tj.

^ "Tajikistan Rejects Iran Visa Offer". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

^ "Turkey opens new consulate in Iran". www.iran-daily.com.

^ "Consulate General of Turkey in Mashhad, Iran". www.embassypages.com.

^ Onley, James. The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 15.

ISBN 0-19-922810-8.

^ "کنسولگریهای خارجی در خراسان - نشریه زمانه". zamane.info.

^ "مرکز تحقیقاتی _ tarikhsazan". tarikhsazan.blogfa.com.

^ "کنسولگری ها ؛ مستخدمان و مستشاران خارجی در مشهد". mashhadenc.ir.

^ "واضح - سركنسولگري جمهوري قزاقستان در گرگان گلستان گشايش يافت".

^ "Saudi consulate opens in Iranian city of Mashhad". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 12 July 2004.

References

Zabeth, Hyder Reza (1999). Landmarks of Mashhad. Mashhad, Iran: Islamic Research Foundation. ISBN 964-444-221-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mashhad. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mashhad. |

Municipality of Mashhad Official website (in Persian)- Astan Quds Razavi

e-Mashhad at the Wayback Machine (archived 2005-08-19) Mashhad Portal Official website (in Persian)

| Preceded by Isfahan | Capital of Iran (Persia) 1736-1747 | Succeeded by Shiraz |

| Preceded by - | Capital of Afsharid dynasty 1736-1796 | Succeeded by - |

Largest cities or towns in Iran 2016 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Tehran  Mashhad | 1 | Tehran | Tehran | 8,693,706 | 11 | Rasht | Gilan | 679,995 |  Isfahan  Karaj |

| 2 | Mashhad | Razavi Khorasan | 3,001,184 | 12 | Zahedan | Sistan and Baluchestan | 587,730 | ||

| 3 | Isfahan | Isfahan | 1,961,260 | 13 | Hamadan | Hamadan | 554,406 | ||

| 4 | Karaj | Alborz | 1,592,492 | 14 | Kerman | Kerman | 537,718 | ||

| 5 | Shiraz | Fars | 1,565,572 | 15 | Yazd | Yazd | 529,673 | ||

| 6 | Tabriz | East Azarbaijan | 1,558,693 | 16 | Ardabil | Ardabil | 529,374 | ||

| 7 | Qom | Qom | 1,201,158 | 17 | Bandar Abbas | Hormozgan | 526,648 | ||

| 8 | Ahwaz | Khuzestan | 1,184,788 | 18 | Arak | Markazi | 520,944 | ||

| 9 | Kermanshah | Kermanshah | 946,651 | 19 | Eslamshahr | Tehran | 448,129 | ||

| 10 | Urmia | West Azarbaijan | 736,224 | 20 | Zanjan | Zanjan | 430,871 | ||