Rip current

Rip current

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Rip current warning signs posted in English and Spanish at Mission Beach, San Diego, California

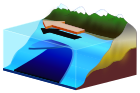

Diagram from above of the workings of a rip current: breaking waves cross a sand bar off the shore. The pushed-in water can most easily travel back out to sea through a gap in the sand bar. This creates a fast-moving rip current.

A rip current, often simply called a rip, or by the misnomer rip tide, is a specific kind of water current which can occur near beaches with breaking waves. A rip is a strong, localized, and narrow current of water which moves directly away from the shore, cutting through the lines of breaking waves like a river running out to sea, and is strongest near the surface of the water.[1]

Rip currents can be hazardous to people in the water. Swimmers who are caught in a rip current and who do not understand what is going on, and who may not have the necessary water skills, may panic, or exhaust themselves by trying to swim directly against the flow of water. Because of these factors, rips are the leading cause of rescues by lifeguards at beaches, and rips are the cause of an average of 46 deaths by drowning per year in the United States.

A rip current is not the same thing as undertow, although some people use the term incorrectly when they often mean a rip current. Contrary to popular belief, neither rip nor undertow can pull a person down and hold them under the water. A rip simply carries floating objects, including people, out beyond the zone of the breaking waves.

Contents

1 Causes and occurrence

1.1 Technical explanation

2 Visible signs and characteristics

3 Danger to swimmers

3.1 Management

4 Uses

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Causes and occurrence[edit]

A rip current forms because wind and breaking waves push surface water towards the land, and this causes a slight rise in the water level along the shore. This excess water will tend to flow back to the open water via the route of least resistance. When there is a local area which is slightly deeper, or a break in an offshore sand bar or reef, this can allow water to flow offshore more easily, and this will initiate a rip current through that gap.

Water that has been pushed up near the beach flows along the shore towards the outgoing rip as "feeder currents", and then the excess water flows out at a right angle to the beach, in a tight current called the "neck" of the rip. The "neck" is where the flow is most rapid. When the water in the rip current reaches outside of the lines of breaking waves, the flow disperses sideways, loses power, and dissipates in what is known as the "head" of the rip.

Rip currents can often occur on a gradually shelving shore where breaking waves approach the shore parallel to it, or where underwater topography encourages outflow at a specific area. Rip currents can form at the coasts of oceans, seas, and large lakes, whenever there are waves of sufficient energy. The location of rip currents can be difficult to predict; whereas some tend to recur always in the same places, others can appear and disappear suddenly at various locations along the beach. The appearance and disappearance of rip currents is dependent on the bottom topography and the exact direction that the surf and swells are coming in from.[2]

Rip currents can potentially occur wherever there is strong longshore variability in wave breaking. This variability may be caused by such features as sandbars (as shown in the animated diagram), by piers and jetties, and even by crossing wave trains, and are often located in places such as where there is a gap in a reef or low area on a sandbar. Rip currents may deepen the channel through a sandbar once they have formed.

Rip currents are usually quite narrow, but tend to be more common, wider, and faster, when and where breaking waves are large and powerful. Local underwater topography makes some beaches more likely to have rip currents; a few beaches are notorious in this respect.[3]

Although rip tide is a misnomer, in areas of significant tidal range, rip currents may only occur at certain stages of the tide, when the water is shallow enough to cause the waves to break over a sand bar, but deep enough for the broken wave to flow over the bar. (In parts of the world with a big difference between high tide and low tide, and where the shoreline shelves gently, the distance between a bar and the shoreline may vary from a few feet to a mile or more, depending whether it is high tide or low tide.)

A fairly common misconception is that rip currents can pull a swimmer down, under the surface of the water. This is not true, and in reality a rip current is strongest close to the surface, as the flow near the bottom is slowed by friction.

The surface of a rip current may appear to be a relatively smooth area of water, without any breaking waves, and this deceptive appearance may cause some beach goers to believe it is a suitable place to enter the water.[4]

Technical explanation[edit]

A more detailed description involves radiation stress. This is the force (or momentum flux) exerted on the water column by the presence of the wave. As a wave shoals and increases in height prior to breaking, radiation stress increases.[clarification needed] To balance this, the local mean surface level (the water level with the wave averaged out) drops; this is known as setdown. As the wave breaks and continues to reduce in height, the radiation stress decreases.[clarification needed] To balance this force,[clarification needed] the mean surface increases — this is known as setup. As a wave propagates over a sandbar with a gap (as shown in the lead image), the wave breaks on the bar, leading to setup. However, the part of the wave that propagates over the gap does not break, and thus setdown will continue. Thus, the mean surface over the bars is higher than that over the gap, and a strong flow issues outward through the gap.[clarification needed]

Visible signs and characteristics[edit]

Some man-made signs warning of rip currents.

Disruption in the line of a breaking wave makes a rip current visible.

Rip currents have a characteristic appearance, and, with some experience, they can be visually identified from the shore before entering the water. This is useful to lifeguards, swimmers, surfers, boaters, divers and other water users, who may need to avoid a rip, or in some cases make use of the current flow. Rip currents often look a bit like a road or a river running straight out to sea, and are easiest to notice and identify when the zone of breaking waves is viewed from a high vantage point. The following are some characteristics that can be used to visually identify a rip:[5]

- A noticeable break in the pattern of the waves — the water often looks flat at the rip, in contrast to the lines of breaking waves on either side of the rip.

- A "river" of foam — the surface of the rip sometimes looks foamy, because the current is carrying foam from the surf out to open water.

- Different color — the rip may differ in color from the surrounding water; it is often more opaque, cloudier, or muddier, and so, depending on the angle of the sun, the rip may show as darker or lighter than the surrounding water.

- It is sometimes possible to see that foam or floating debris on the surface of the rip is moving out, away from the shore. In contrast, in the surrounding areas of breaking waves, floating objects are being pushed towards the shore.

These characteristics are helpful in learning to recognize and understand the nature of rip currents so that a person can recognize the presence of rips before entering the water. In the United States, some beaches have signs created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and United States Lifesaving Association, explaining what a rip current is and how to escape one. These signs are titled, "Rip Currents; Break the Grip of the Rip".[6] Beachgoers can get information from lifeguards, who are always watching for rip currents, and who will move their safety flags so that swimmers can avoid rips.

Danger to swimmers[edit]

Warning sign on the trail to Hanakapiai Beach, Hawaii.

Rip currents are a potential source of danger for people in shallow water with breaking waves in seas, oceans and lakes.[5] Rip currents are the proximate cause of 80% of rescues carried out by beach lifeguards.[7]

Rip currents typically flow at about 0.5 metres per second (1–2 feet per second), but they can be as fast as 2.5 metres per second (8 feet per second), which is faster than any human can swim. However, most rip currents are fairly narrow, and even the widest rip currents are not very wide; swimmers can easily exit the rip by swimming at a right angle to the flow, parallel to the beach. Swimmers who are unaware of this fact may exhaust themselves trying unsuccessfully to swim against the flow.[2] The flow of the current also fades out completely at the head of the rip, outside the zone of the breaking waves, so there is a definite limit to how far the swimmer will be taken out to sea by the flow of a rip current.

In a rip current, death by drowning occurs when a person has limited water skills and panics, or when a swimmer persists in trying to swim to shore against a strong rip current, thus eventually becoming exhausted and unable to stay afloat.

According to NOAA, over a 10-year average, rip currents cause 46 deaths annually in the United States, and 64 people died in rip currents in 2013.[8] However, the United States Lifesaving Association "estimates that the annual number of deaths due to rip currents on our nation's beaches exceeds 100."[6]

A study published in 2013 in Australia revealed that rips killed more people on Australian territory than bushfires, floods, cyclones and shark attacks combined.[9]

Management[edit]

A warning sign in France

People caught in a rip current may notice that they are moving away from the shore quite rapidly. It is often not possible to swim directly back to shore against a rip current, so this is not recommended. Contrary to popular misunderstanding, a rip does not pull a swimmer under the water, it simply carries the swimmer away from the shore in a narrow band of moving water.[1] The rip is like a moving treadmill, which the swimmer can get out of by swimming across the current, parallel to the shore, in either direction, until out of the rip current, which is usually not very wide. Once out of the rip, swimming back to shore is relatively easy in areas where waves are breaking and where floating objects and swimmers are being pushed towards the shore.[10]

As an alternative, swimmers who are caught in a strong rip can relax and go with the flow (either floating or treading water) until the current dissipates beyond the surf line, and then they can signal for help, or swim back through the surf diagonally away from the rip and towards the shore.[2]

It is necessary for coastal swimmers to understand the danger of rip currents, to learn how to recognize them and how to deal with them, and if possible to swim in only those areas where lifeguards are on duty.[5]

Uses[edit]

Experienced and knowledgeable water users, including surfers, body boarders, divers, surf lifesavers and kayakers, will sometimes use rip currents as a rapid and effortless means of transportation when they wish to get out beyond the breaking waves.[11]

See also[edit]

- Longshore drift

Rip current statement — warnings issued by the U.S. National Weather Service

- Undertow (water waves)

References[edit]

^ ab "Rip Current Characteristics". College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, University of Delaware. Retrieved 2009-01-16..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc "Rip Currents". United States Lifesaving Association. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

^ "Rip currents at Ocean Beach are severe hazard for unwary, UC Berkeley expert warns". University of California, Berkeley. 2002-05-23. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

^ Don't get sucked in by the rip... on YouTube

^ abc "Rip Currents Safety". U.S. National Weather Service. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

^ ab "NOAA Reminds Swimmers That Rip Currents Can Be a Threat. Rip Current Awareness Week Is June 1–7, 2008" (Press release). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2008-06-02. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

^ "NWS Rip Current Safety Home Page". U.S. National Weather Service. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

^ "NWS Weather Fatality, Injury and Damage Statistics". NOAA. 2018-04-25.

^ "Rips more deadly than bushfires and sharks". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

^ "Beach and Surf Safety". Science of the Surf. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

^ Cowan, C. L. "Ride the Rip". Paddling.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-17. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rip currents. |

- NOAA glossary of terms used in describing rip currents

Categories:

- Physical oceanography

- Bodies of water

- Surf lifesaving

- Oceanographical terminology

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.452","walltime":"0.559","ppvisitednodes":{"value":1756,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":93047,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":2802,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":12,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":2,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":26698,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":1,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 351.040 1 -total"," 41.97% 147.324 1 Template:Reflist"," 28.88% 101.373 9 Template:Cite_web"," 19.27% 67.639 4 Template:Clarify"," 17.14% 60.173 4 Template:Fix-span"," 10.61% 37.258 4 Template:Navbox"," 8.72% 30.615 1 Template:Short_description"," 8.12% 28.511 1 Template:Pagetype"," 8.07% 28.313 4 Template:Replace"," 7.42% 26.062 1 Template:Commons_category"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.164","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":5168500,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1239","timestamp":"20181026161752","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":99,"wgHostname":"mw1320"});});