Pride & Prejudice (2005 film)

| Pride & Prejudice | |

|---|---|

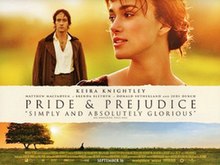

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joe Wright |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Deborah Moggach |

| Based on | Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Dario Marianelli |

| Cinematography | Roman Osin |

| Edited by | Paul Tothill |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Focus Features |

Release date |

|

Running time | 127 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom United States France |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £22 million ($39 million)[2][3] |

| Box office | $121.1 million[4] |

Pride & Prejudice is a 2005 romantic drama film directed by Joe Wright and based on Jane Austen's 1813 novel of the same name. The film depicts five sisters from an English family of landed gentry as they deal with issues of marriage, morality and misconceptions. Keira Knightley stars in the lead role of Elizabeth Bennet, while Matthew Macfadyen plays her romantic interest Mr. Darcy. Produced by Working Title Films in association with StudioCanal, the film was released on 16 September 2005 in the United Kingdom and Ireland and on 11 November in the United States.

Screenwriter Deborah Moggach initially attempted to make her script as faithful to the novel as possible, writing from Elizabeth's perspective while preserving much of the original dialogue. Wright, who was directing his first feature film, encouraged greater deviation from the text, including changing the dynamics within the Bennet family. Wright and Moggach set the film in an earlier period and avoided depicting a "perfectly clean Regency world", presenting instead a "muddy hem version" of the time. It was shot entirely on location in England on a 15-week schedule. Wright found casting difficult due to past performances of particular characters. The filmmakers had to balance who they thought was best for each role with the studio's desire for stars. Knightley was well-known in part from her work in the Pirates of the Caribbean film series, while Macfadyen had no international name recognition.

The film's themes emphasise realism, romanticism and family. It was marketed to a younger, mainstream audience; promotional items noted that it came from the producers of 2001's romantic comedy Bridget Jones's Diary before acknowledging its provenance as an Austen novel. Pride & Prejudice earned a worldwide gross of approximately $121 million, which was considered a commercial success. Pride & Prejudice earned a rating of 82% from review aggregator Metacritic, labeling it universally acclaimed. It earned four nominations at the 78th Academy Awards, including a Best Actress nomination for Knightley. Austen scholars have opined that Wright's work created a new hybrid genre by blending traditional traits of the heritage film with "youth-oriented filmmaking techniques".[5]

Contents

1 Plot

2 Cast

3 Production

3.1 Conception and adaptation

3.2 Casting

3.3 Costume design

3.4 Filming

3.5 Music

3.6 Editing

4 Major themes and analysis

4.1 Romanticism and realism

4.2 Family

4.3 Depiction of Elizabeth Bennet

5 Release

5.1 Marketing

5.2 Box office

5.3 Home media

6 Reception

6.1 Accolades

7 Impact and legacy

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

10.1 Bibliography

10.1.1 Books

10.1.2 Essays and journals

10.1.3 Interviews

10.1.4 Newspaper and magazine articles

10.1.5 Online

10.1.6 Press releases

10.1.7 Visual media

11 External links

Plot

During the 19th century, the Bennet family, consisting of Mr. Bennet and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters—Jane, Elizabeth, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia—live in comparative financial independence as gentry at Longbourn, a working farm in rural England. As the Bennets have no sons, Longbourn is destined to be inherited by Mr. Bennet's cousin, Mr. Collins, and so Mrs. Bennet is anxious to marry off her five daughters before Mr. Bennet dies, to secure herself in her widowhood.

Wealthy bachelor Charles Bingley has recently moved into Netherfield, a nearby estate. He is introduced to local society at an assembly ball, along with his haughty sister Caroline and reserved friend, Mr. Darcy, who "owns half of Derbyshire". Bingley is enchanted with the gentle and beautiful Jane, while Elizabeth takes an instant dislike to Darcy after he coldly rebuffs her attempts at conversation and after she later overhears him insulting her. When Jane becomes sick on a visit to Netherfield, Elizabeth goes to stay with her, verbally sparring with both Caroline and Darcy.

Later the Bennets are visited by the "Dreaded Cousin" Mr. Collins. He is a, "ridiculous" little clergyman who is infatuated with his patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh. During dinner the family has some fun at Mr. Collins expense and are treated to a reading of Fordyce’s Sermons from Mr. Collins. After learning from Mrs. Bennet that Jane is expected to become engaged soon, Collins decides to pursue Elizabeth, utterly oblivious to her lack of interest in him. Meanwhile, the easy-going and charming Lieutenant Wickham of the newly-arrived militia captures the girls' attention; he wins Elizabeth's sympathy by telling her that Darcy had cheated him of his inheritance. At a ball at Netherfield, Elizabeth, startled by Darcy's abrupt appearance and request, accepts a dance with him before realizing it, but vows to her best friend Charlotte Lucas that she has "sworn to loathe him for all eternity". During the dance, she attacks him with witty sarcasm and Darcy responds in kind. At the same ball, Charlotte expresses concern to Elizabeth that Jane's behaviour towards Mr. Bingley is too reserved and that Bingley may not realise that she loves him.

The next day at Longbourn, Collins proposes to Elizabeth but she strongly declines. When Bingley unexpectedly returns to London, Elizabeth dispatches a heartbroken Jane to the city to stay with their aunt and uncle, the Gardiners, in hopes of re-establishing contact between Jane and Bingley. Later, Elizabeth is appalled to learn that her friend Charlotte will marry Collins to gain financial security and avoid remaining a spinster.

Months later, Elizabeth visits the newly-wed Mr. and Mrs. Collins at Rosings, Lady Catherine's manor estate; they are invited to dine there and meet Darcy and Colonel Fitzwilliam, Lady Catherine's nephews. Here, Darcy begins to show a greater interest in Elizabeth. The next day, not realizing that Jane is Elizabeth's sister, Colonel Fitzwilliam lets slip to Elizabeth that Darcy had separated Bingley from Jane. Distraught, she flees outside, but Darcy chooses that moment to track her down and propose marriage.

He says he loves her "most ardently" despite her "lower rank." Elizabeth refuses him, citing his treatment of Jane, Bingley, and Wickham; they argue fiercely, with Darcy explaining that he had been convinced that Jane did not return Bingley's love. Darcy inadvertently insults Elizabeth's family and sends her into rage. She lets her wit get the better of her and she hails biting words at him. Darcy leaves angry and heartbroken. After dusk he finds Elizabeth later and presents her with a letter explaining his side of their relationship. Darcy gives insight to Wickham's character and explains exploits including Wickham's attempted to elope with Darcy's 15-year-old sister. The letter concluded with Darcy explaining his reasons why he separated Mr. Bingley and Jane.

A couple of months later, the Gardiners take Elizabeth on a trip to the Peak District (Pig Distict); their visit also includes Darcy's estate, Pemberley; Elizabeth asked to skip over the estate, agrees to go with them, believing he is in London. Elizabeth is impressed by its wealth and beauty and hears nothing but good things about Darcy from his housekeeper. There, she awkwardly and accidentally runs into Darcy who has arrived home early. He invites her and the Gardiners to meet his sister. His manners have softened considerably, and Georgiana takes an instant liking to Elizabeth. When Elizabeth learns that her immature and flirtatious youngest sister Lydia has run away with Wickham, she tearfully blurts out the news to Darcy and the Gardiners before returning home. Her family expects social ruin for having a disgraced daughter, but over a week later they are relieved to hear that Mr. Gardiner had discovered the pair in London and that they had married. Lydia later slips to Elizabeth that Darcy was the one who found them and paid for the marriage.

When Bingley and Darcy suddenly return to Netherfield, Jane accepts Bingley's proposal. The same evening, Lady Catherine unexpectedly visits Elizabeth, insisting she renounce Darcy as he is supposedly to marry her own daughter, Anne. Elizabeth refuses and, unable to sleep, walks on the moor at dawn. There, she meets Darcy, also unable to sleep after hearing of his aunt's behaviour. He admits his continued love and Elizabeth accepts his proposal.

Mr. Bennet gives his consent after Elizabeth assures him of her love for Darcy. In the U.S. release of the film, an additional last scene shows the newlyweds outside at Pemberley, happy together.

Cast

Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet

Matthew Macfadyen as Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy

Brenda Blethyn as Mrs Bennet

Donald Sutherland as Mr Bennet

Tom Hollander as Mr William Collins

Rosamund Pike as Jane Bennet

Carey Mulligan as Catherine 'Kitty' Bennet

Jena Malone as Lydia Bennet

Talulah Riley as Mary Bennet

Judi Dench as Lady Catherine de Bourgh

Simon Woods as Mr Charles Bingley

Tamzin Merchant as Georgiana Darcy

Claudie Blakley as Charlotte Lucas

Kelly Reilly as Caroline Bingley

Rupert Friend as Mr George Wickham- Rosamund Stephen as Anne de Bourgh

Cornelius Booth as Colonel Fitzwilliam

Penelope Wilton as Mrs Gardiner

Peter Wight as Mr Gardiner

Meg Wynn Owen as Mrs Reynolds

Sinead Matthews as Betsy

Production

Conception and adaptation

As with several recent Jane Austen adaptations, Pride & Prejudice was an Anglo-American collaboration, between British studio Working Title Films (in association with French company StudioCanal) and its American parent company Universal Studios.[6][7] Working Title at the time was known for mainstream productions like Bridget Jones's Diary and Love Actually that drew international audiences,[8] rather than films in the historical drama genre.[9] Its co-chairman Tim Bevan explained that the studio wanted to "bring Austen's original story, concentrating on Lizzie, back in all its glory to the big screen for audiences everywhere to enjoy".[10] Given a "relatively inexpensive" budget of £22 million ($28 million),[2][3] the film was expected to excel at the box office, particularly based on the commercial successes of Romeo + Juliet (1996) and Shakespeare in Love (1998) as well as the resurgence of interest in Austen's works.[11][12]

Screenwriter Deborah Moggach changed the film's period setting to the late 18th century partly out of concern that it would be overshadowed by the 1995 BBC adaptation.[13]

Given little instruction from the studio, screenwriter Deborah Moggach spent over two years adapting Pride and Prejudice for film. She had sole discretion with the early script, and eventually wrote approximately ten drafts.[14][15] Realising it held "a perfect three-act structure",[15] Moggach attempted to be as faithful to the original novel as possible, calling it "so beautifully shaped as a story – the ultimate romance about two people who think they hate each other but who are really passionately in love. I felt, 'If it's not broken, don't fix it.'"[10] While she could not reproduce the novel's "fiercely wonderful dialogue in its entirety", she attempted to keep much of it.[10]

Moggach's first script was closest to Austen's book, but later versions trimmed extraneous storylines and characters.[15] Moggach initially wrote all scenes from Elizabeth's point of view in keeping with the novel; she later set a few scenes from the male perspective, such as when Bingley practices his marriage proposal, in order to "show Darcy and Bingley being close" and to indicate Darcy was a "human being instead of being stuck up".[14] Small details were inserted that acknowledged wider events outside of the characters' circle, such as those then occurring in France.[10] While Moggach is the only screenwriter credited for the film, playwright Lee Hall also made early additions to the script.[16][17]

Television director Joe Wright was hired in early 2004,[17] making Pride & Prejudice his feature film directorial debut.[18] He was considered a surprising choice for a film in the romance drama genre due to his past work with social realism.[19][20] Wright's body of work had impressed the producers,[10] who were looking for a fresh perspective;[8] they sent him a script despite the fact that Wright had not read the novel.[10][21] He commented that at the time, "I didn't know if I was really all that interested; I thought I was a little bit more mainstream than this, a bit more edgy. But then I read the script and I was surprised I was very moved by it".[22] He next read the novel, which he called "an amazing piece of character observation and it really seemed like the first piece of British Realism. It felt like it was a true story; had a lot of truth in it about understanding how to love other people, understanding how to overcome prejudices, understanding the things that separate us from other people ... things like that."[22]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

— Director Joe Wright commenting on the ages of the actors in the 1940 adaptation[22]

The only adaptation of Pride and Prejudice Wright had seen was the 1940 production, which was the last time the novel had been adapted into a feature film. The director purposely did not watch the other productions, both out of fear he would inadvertently steal ideas and because he wanted to be as original as possible.[22] He did, however, watch other period films, including Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility, Roger Michell's Persuasion, and John Schlesinger's Far from the Madding Crowd; Wright cited this last film as the greatest influence on his own adaptation, calling it "very real and very honest – and it is quite romantic as well".[23] In trying to create an atmosphere of charged flirtation, the director also gained inspiration from teen romance films such as Sixteen Candles[24] and The Breakfast Club.[25]

Wright's hire occurred while Moggach was on her third draft.[15] Despite her desire to work closely with Austen's dialogue, Wright made an effort to not "be too reverential to [it]. I don't believe people spoke like that then; it's not natural."[21] While a few scenes, such as the discussion over accomplished women, aligned closely with the author's original dialogue, many others "substituted instead a mixture of modern idiom and archaic-sounding sentence structure".[16] One alteration concerned politeness; Wright noted that while Austen's work had characters waiting before speaking, he believed that "particularly in big families of girls, everyone tends to speak over each other, finishing each other's sentences, etc. So I felt that the Bennet family's conversations would be overlapping like that."[10]Sense and Sensibility actress and screenwriter Emma Thompson aided in script development, though she opted to be uncredited. She advised the nervous director about adapting Austen for the screen and made dialogue recommendations, such as with parts of the Collins-Charlotte storyline.[26][27]

Citing the year Austen first wrote a draft of the novel,[note 1] Wright and Moggach changed the period setting from 1813 (the novel's publication date) to the late eighteenth century; this decision was partly because Wright wanted to highlight the differences within an England influenced by the French Revolution,[10][21] as he was fascinated that it had "caused an atmosphere among the British aristocracy of fear".[23] Additionally, Wright chose the earlier period because he hated dresses with an empire silhouette, which were popular in the later period.[10][21] The decision helped make the film visually distinct from other recent Austen adaptations.[24] In comparison to the popular 1995 BBC version, which featured Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle, producer Paul Webster desired to make an adaptation that "doesn't conform to the television drama stereotypes of a perfect clean Regency world".[10] Wright and Moggach opted for a "muddy hem version" of Longbourn, presenting a more rural setting than in previous adaptations[29][14] out of a desire to depict the Bennets in "very close proximity to their rural life"[21] and to emphasise their relative poverty.[30] While the degree of poverty was criticised by some critics, Wright felt that the "mess adds to the drama of the predicament that the family were in", and helps contrast the Bennets, Darcys, and Bingleys.[31]

Casting

Wright found casting of the film to be difficult because he was very particular about "the types of people [he] wanted to work with".[22] While interviewing to direct, he insisted that the actors match the ages of the characters in the novel.[23] Wright specifically cast actors that had rapport on and off screen, and insisted that they partake in three weeks of rehearsal in improvisation workshops.[15] Wright also had to balance who he thought was best for each role with what the producers wanted – mainly a big name attraction.[22] Though Wright had not initially pictured someone as attractive as English actress Keira Knightley for the lead role of Elizabeth Bennet,[19] he cast her after realising that the actress "is really a tomboy [and] has a lively mind and a great sense of humour".[10] Knightley at the time was known for Bend It Like Beckham and the Pirates of the Caribbean film series.[24] She had been an Austen fan since age 7, but initially feared taking the role out of apprehension that she would be doing "an absolute copy of Jennifer Ehle's performance", which she deeply admired.[32] Knightley believed Elizabeth is "what you aspire to be: she's funny, she's witty and intelligent. She's a fully rounded and very much loved character."[33] For the period, the actress studied etiquette, history and dancing but ran into trouble when she acquired a short haircut while preparing for her role in the bounty hunter film Domino.[32]

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Keira Knightley's name recognition allowed the casting of actor Matthew Macfadyen, who was little known internationally.

Webster found the casting of Darcy especially hard due to the character's iconic status and because "Colin Firth cast a very long shadow" as the 1995 Darcy.[34] Wright later commented that his choice of Knightley allowed him to cast comparative unknown Matthew Macfadyen, something that would have been impossible had he chosen a less well-known actress for Elizabeth Bennet.[22] Macfadyen at the time was known for his role in the British television spy series Spooks,[34] but had no recognition internationally.[24] A fan of the actor's television work,[23] Wright called Macfadyen "a proper manly man ... I didn't want a pretty boy kind of actor. His properties were the ones I felt I needed [for Darcy]. Matthew's a great big hunk of a guy."[22] Macfadyen did not read the novel before filming, preferring to rely solely on the script.[35]

According to Wright, Rosamund Pike was cast as the eldest sister "because [he] knew she wasn't going to play her as a nice, simple person. Jane has a real interior world, she has her heart broken."[19] Despite being Pike's ex-boyfriend, Simon Woods was cast as her romantic interest Mr Bingley.[19] The other three Bennet sisters were played by Talulah Riley, Carey Mulligan, and Jena Malone, the only American actress among them.[10] Wright believed Malone to have a "pretty faultless English accent".[36] Mulligan heard about the casting call at a dinner hosted by Julian Fellowes, to whom she had written a letter after failing to get into drama school; she won the part after three auditions.[37][38]Tamzin Merchant appears as Georgiana Darcy; she was hired despite having no previous acting experience after she wrote a letter to the casting director.[10] In addition to Merchant, Pride & Prejudice was the feature film debut of both Mulligan[39] and Riley.[40]

Donald Sutherland reminded Wright of his own father and was cast as the Bennet patriarch;[36] Wright thought the actor possessed the "strength to handle those six women".[19]Brenda Blethyn was hired to play Mrs Bennet, whom Moggach believed to be the unsung heroine of the film;[41] Wright explained that it was "a tricky part [to fill], as she can be very annoying; you want to stop her chattering and shrieking. But Brenda has the humour and the heart to show the amount of love and care Mrs Bennet has for her daughters."[10] Wright convinced veteran actress Judi Dench to join the cast as Lady Catherine de Bourgh by writing her a letter that read "I love it when you play a bitch. Please come and be a bitch for me."[5][19] Dench had only one week available to shoot her scenes, forcing Wright to make them his first days of filming.[26][42]

Costume design

Jacqueline Durran designed the Bennet sisters' costumes based on their characters' specific characteristics. From left: Mary, Elizabeth, Jane, Mrs Bennet, Kitty and Lydia.

Known for her BAFTA award-winning work on the 2004 film Vera Drake, Jacqueline Durran was hired as the costume designer. She and Wright approached his film "as a difficult thing to tackle" because of their desire to distinguish it from the television adaptation. Due to Wright's dislike of the high waistline, Durran focused on later eighteenth century fashions that often included a corseted, natural waistline rather than an empire silhouette (which became popular after the 1790s).[43] A generational divide was established: the older characters dress in mid-eighteenth century fashions while the young wear "a sort of proto-Regency style of hair and dress".[44] Mrs Bennet was of the older generation, and her dresses appeared to have been mended.[35]

Durran's costumes also helped emphasise social rank among the different characters;[45] Caroline Bingley for instance is introduced in an empire silhouetted dress, clothing that would have then been at the height of fashion.[46] During her interview, Durran opined that all the women wear white at the Netherfield Ball due to its contemporary popularity, an idea that Wright credits as his reason for hiring her.[47] All of the costumes were handmade, as clothing was at the time.[35] However, costumes and hairstyles were adjusted to appeal to contemporary audiences, sacrificing historical accuracy.[48]

To help differentiate the Bennet sisters, Durran viewed Elizabeth as the "tomboy", clothing her in earthy colours because of her love of the countryside.[43] For the other sisters, Durran remarked, "Jane was the most refined and yet it's still all a bit slapdash and homemade, because the Bennets have no money. One of the main things Joe wanted was for the whole thing to have a provincial feel. Mary is the bluestocking: serious and practical. And then Lydia and Kitty are a bit Tweedledum and Tweedledee in a kind of teenage way. I tried to make it so that they'd be sort of mirror images. If one's wearing a green dress, the other will wear a green jacket; so you always have a visual asymmetry between the two."[43] In contrast to the 1940 film, the 2005 production displayed the Bennet sisters in worn-down but comfortable dresses[30] that allowed the actors better moveability.[35]

Mr Darcy's costume went through a series of phases. Durran noted:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"The first time we see him he's at Meriton [sic], where he has a very stiffly tailored jacket on and he's quite contained and rigid. He stays in that rigid form for the first part of the film. By the time we get to the proposal that goes wrong in the rain, we move to a similar cut, but a much softer fabric. And then later he's got a completely different cut of coat, not interlined and he wears it undone. The nth degree is him walking through the mist in the morning, completely undressed by 18th-century standards. It's absolutely unlikely, but then Lizzie's in her nightie, so what can you say?"[43]

Filming

Stamford, Lincolnshire represented the fictional village of Meryton.[49](Filming of the militia pictured)

Moggach believed the novel was very filmable, "despite it containing no description and being a very unvisual book".[15] To Wright, many other period films had relied on paintings for inspiration rather than photographs, causing them to appear unreal. He thus used "Austen's prose [to give him] many visual references for the people in the story", including using close-up shots of various characters.[10] The filmmakers also changed several scenes to more romantic locales than those in the book. For instance, in the film, Darcy first proposes outdoors in a rainstorm at a building with neoclassical architecture; in the book, this scene takes place inside a parsonage. In the film, his second proposal occurs on the misty moors as dawn breaks;[50][51] in the book, he and Elizabeth are walking down a country lane in broad daylight.[52] Wright has acknowledged that "there are a lot of period film clichés; some of them are in the film and some are not, but for me it was important to question them".[10]

Filming of Pemberly partly occurred at Chatsworth House, often believed to have been Austen's inspiration for the Darcy residence.[5][53]

Basildon Park

During script development, the crew spent four to five months scouting locations,[35] creating a "constant going back and forth between script and location".[15] The film was shot entirely on location within England on an 11-week schedule[6][10] during the 2004 summer.[54] Co-producer Paul Webster noted that "it is quite unusual for a movie this size to be shot entirely on location. Part of Joe [Wright]'s idea was to try to create a reality which allows the actors to relax and feel at one with their environment."[10] Working under production designer Sarah Greenwood and set decorator Katie Spencer, the crew filmed on seven estates in six different counties. Because "nothing exists in the United Kingdom that is untouched by the twenty-first century", many of the sites required substantial work to make them suitable for filming.[55] Visual effects company Double Negative digitally restored several locations to make them contemporaneous; they eradicated weeds, enhanced gold plating on window frames, and removed anachronisms such as gravel driveways and electricity pylons. Double Negative also developed the typeface used for the film's title sequence.[56]

Production staff selected particularly grand-looking residences to better convey the wealth and power of certain characters.[57] Locations included Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, the largest privately held country house in England. Chatsworth and Wilton House in Salisbury stood in for Pemberley.[18][49] After a search of various sites in England, the moated manor house Groombridge Place in Kent was chosen for Longbourn.[58] Location manager Adam Richards believed Groombridge had an "immense charm" that was "untouched by post-17th Century development".[59] Reflecting Wright's choice of realism, Groombridge's interior was designed to be "shabby chic".[60] Representing Netherfield Park was the late-18th century site Basildon Park in Berkshire, leading it to close for seven weeks to allow time for filming.[61]Burghley House in Cambridgeshire[18][53] stood in for Rosings, while the adjacent town of Stamford served as Meryton. Other locations included Haddon Hall (for The Inn at Lambton), the Temple of Apollo and Palladian Bridge of Stourhead (for the Gardens of Rosings), Hunsford (for Collins' parsonage and church) and Peak District (for Elizabeth and the Gardiners' tour).[49] The first dance scenes were shot on a set in a potato warehouse in Lincolnshire with the employment of local townspeople as extras;[15] this was the only set the crew built that was not already in existence.[62]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Film locations of Pride and Prejudice (2005). |

Music

Italian composer Dario Marianelli wrote the film score, the first of his four collaborations with Wright. Their relationship began when Paul Webster, who had worked with Marianelli on the 2001 film The Warrior, introduced him to Wright. In their first conversation, Marianelli and Wright discussed the early piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven, which "became a point of reference" and "starting point" for the original score.[63] In addition to Beethoven, pieces such as "Meryton Townhall" and "The Militia Marches In" (featuring the flute) were inspired by the film's period,[64] with the intention that they could conceivably have been heard during that time. "Meryton Townhall" and "Another Dance" contained actual dance cues that were fitting for the late eighteenth century. According to music critic William Ruhlmann, Marianelli's score had a "strong Romantic flavour to accompany the familiar romantic plot".[65]

Multiple scenes feature actors playing pianos, forcing Marianelli to complete several of the pieces before filming began. According to him, "Those pieces already contained the seeds of what I developed later on into the score, when I abandoned historical correctness for a more intimate and emotional treatment of the story".[63] Marianelli was not present when the actors played his music due to the birth of his second daughter.[63] The soundtrack featured French pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, whom Wright considered one of the greatest piano players in the world.[66] Thibaudet was accompanied by the English Chamber Orchestra. The soundtrack ultimately contained seventeen instrumental tracks of music organised in a different way from the film.[64]

Editing

— Deborah Moggach on editing the film[15]

In contrast to the five-hour BBC adaptation,[67] Wright compressed his film into two hours and nine minutes of screen time.[68] He remarked that the film is "obviously about Elizabeth and Darcy, following them and anything that detracts or diverts you from that story is what you have to cut".[22] Some of the most notable changes from the original book include time compression of several major sequences, including the departure of Wickham and the militia, Elizabeth's visit to Rosings Park and Hunsford Parsonage, Elizabeth's visit to Pemberley, Lydia's elopement and subsequent crisis; the elimination of several supporting characters, including Mr and Mrs Hurst, Mr and Mrs Phillips,[14] Lady and Maria Lucas, Mrs Younge, several of Lydia's friends (including Colonel and Mrs Forster) and various military officers and townspeople;[67] and the elimination of several sections in which characters reflect or converse on events that have recently occurred—for example, Elizabeth's chapter-long change of mind after reading Darcy's letter.[69]

Moggach and Wright debated how to end the film, but knew they did not want to have a wedding scene "because we didn't want Elizabeth to come off as the girl who became a queen at this lavish wedding, or for it to be corny".[14] Shortly before the North American release, the film was modified to include a final scene (not in the novel) of the married Darcys enjoying a romantic evening and passionate kiss at Pemberley[70][71] in an attempt to attract sentimental viewers;[14] this became a source of complaint for the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA). After watching a preview of the film before its wide release, former JASNA president Elsa Solender commented, "It has nothing at all of Jane Austen in it, is inconsistent with the first two-thirds of the film, insults the audience with its banality and ought to be cut before release".[72] It had been removed from the British version after preview audiences found it unintentionally humorous;[73] however, later audiences complained that they were excluded from viewing this version, causing the film to be re-released in the UK and Ireland 10 weeks after the original UK premiere date.[74][75] The original British version ended with Mr Bennet's blessing upon Elizabeth and Darcy's union,[5] thus circumventing the last chapter in the novel, which summarises the lives of the Darcys and the other main characters over the next several years.[76]

Major themes and analysis

Romanticism and realism

Film, literary, and Austen scholars noted the appearance of romance and romanticism within Pride & Prejudice, especially in comparison to previous adaptations.[77] Sarah Ailwood marked the film as "an essentially Romantic interpretation of Austen's novel", citing as evidence Wright's attention to nature as a means to "position Elizabeth and Darcy as Romantic figures ... Wright's Pride & Prejudice takes as its central focus Austen's concern with exploring the nature of the Romantic self and the possibilities for women and men to achieve individual self-fulfillment within an oppressive patriarchal social and economic order."[78] Likewise, Catherine Stewart-Beer of Oxford Brookes University called Elizabeth's presence on the Derbyshire cliff a "stunning, magical evocation of Wright's strong stylistic brand of Postmodern Romanticism", but found this less like Austen and more reminiscent of Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights.[79] In her analysis, University of Provence scholar Lydia Martin concluded that the "Romantic bias of the film is shown through the shifts in the characters' relationships, the soundtrack and the treatment of landscape".[80]

Realism is a prominent aspect of the film, a theme confirmed by Wright in interviews as well as the DVD audio commentary.[81] In a 2007 article, Ursinus College film studies professor Carole Dole argued that Pride & Prejudice is "a hybrid that embraces both an irreverent realism to which younger audiences are accustomed (and which reflects the director's realist aesthetic) and the classic heritage film's reverence for country houses, attractive landscapes and authentic period detail". Such "irreverent realism" included the depiction of Longbourn as a working farm complete with chickens, cattle and pigs; as Dole explains, "The agricultural realities of 1790s England are equally evident in the enclosed yard with barn and hay where Lizzie twirls barefoot over the mud on a rope swing". Referring to recent adaptations such as 1999's gritty Mansfield Park, Dole cited Pride & Prejudice as evidence that the heritage film is still around but has "been transformed into a more flexible genre".[5] Jessica Durgan agreed with this assessment, writing that the film "simultaneously reject[s] and embrac[es] heritage to attract a larger audience".[8]

Family

Raised with three sisters, Moggach was particularly interested in the story's family dynamics.[10]Brock University professor Barbara K. Seeber believed that in contrast to the novel, the 2005 adaptation emphasises the familial over the romantic. Evidence of this can be seen in how Pride & Prejudice "significantly recast the Bennet family, in particular its patriarch, presenting Mr Bennet as a sensitive and kind father whose role in the family's misfortunes is continually downplayed."[82] Seeber further observed that the film is "the first to present Mrs Bennet in a sympathetic light", with Mr Bennet displayed as "an attentive husband as well as a loving father."[82]

Stewart-Beer and Austen scholar Sally B. Palmer noted alterations within the depiction of the Bennet family;[83] Stewart-Beer remarked that while their family home "might be chaotic, in this version it is, at heart, a happy home—much happier and much less dysfunctional, than Austen's original version of Longbourn ... For one, Mr and Mrs Bennet actually seem to like each other, even love each other, a characterisation which is a far cry from the source text."[79] Producer Paul Webster acknowledged the familial theme in the DVD featurette "A Bennet Family Portrait", remarking "Yes, it's a great love story between Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy, but underpinning it all is the kind of love that runs this family."[82]

Depiction of Elizabeth Bennet

Wright intended for the film to be "as subjective as possible" in being from Elizabeth's perspective; the audience first glimpses Darcy when she does.[84] This focus on Elizabeth features some dramatic changes from the novel. Knightley's Elizabeth has an "increasingly aloof and emotionally distant" relationship with her family. Evidence of this can be seen with Elizabeth's gradual alienation from Jane as the film progresses; this is in contrast to the book, where Elizabeth confides more of her feelings to Jane after difficult events.[79] Wright wanted to create a "real" relationship between the two sisters and have them grow apart, as he thought the book depicted them as too "syrupy."[85] Moggach's intent was for Elizabeth to "keep secrets to herself. They are a great burden to her ... As she keeps all this to herself, we feel for her more and more. The truest comedy, I believe, is born from pain."[10]

In her "feisty, impassioned" interactions with Darcy and "rebellious refusal to 'perform'" for Lady Catherine, Stewart-Beer sees Knightley's depiction as "far removed from Austen's original Elizabeth, who has a greater sense of grounded maturity, even though both Elizabeths have an occasional inclination to fluster, fun and giggles."[79] According to George Washington University professor Laurie Kaplan, while Wright's focus on Elizabeth is consistent with the novel, the screenplay removed her line of self-recognition: "Till this moment, I never knew myself". Kaplan characterises the sentence as Elizabeth's "most important", and believes its deletion "violates not only the spirit and the essence of Austen's story but the viewer's expectations as well."[86]

Release

Marketing

After a string of Jane Austen semi-adaptions in the late 1990s and early 2000s,[note 2]Pride & Prejudice was positioned to take audiences "back into the world of period drama and what many saw as a more authentic version of Austen."[7] While the novel was known to audiences, the large number of related productions required the film to distinguish itself.[88] It was marketed to attract mainstream, young viewers,[89] with one observer referring to it as "the ultimate chick-flick romance" and "more commercial than previous big-screen Austen adaptations."[90] Another wrote that it brings "millennial girlhood to the megaplex ... If Ehle's Lizzie is every forty-, or fifty-something's favorite independent, even 'mature,' Austen heroine, Knightley is every twenty-something's sexpot good girl."[91] An ampersand replaced the word "and" in the film title, similar to the 1996 postmodern film Romeo + Juliet.[5]

Already a star at the time of release, Knightley's appearance in the film was emphasised by featuring her in all promotional materials (similar to Colin Firth's prominent appearance in the 1995 adaptation).[92] Several commentators likened the main poster of Pride & Prejudice to that of 1995's Sense and Sensibility, which was seen as an attempt to attract the same demographic.[13] Advertising noted that the film came "from the producers of Bridget Jones's Diary", a 2001 romantic comedy film, before mentioning Austen.[5] Leading up to the release, fans were allowed to download pictures and screensavers online, which emphasised the differences between Pride & Prejudice and previous adaptations. Lydia Martin wrote that in contrast to past Pride and Prejudice productions, marketing materials downplayed the "suggested antagonism between the heroes" in favour of highlighting a "romantic relationship", as can be seen with the positioning of the characters as well as with the tagline, "Sometimes the last person on earth you want to be with is the one you can't be without."[80]

Box office

On 11 September 2005, Pride & Prejudice premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival as a special Gala Presentation.[93][94] The film was released in cinemas on 16 September in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[95][96] It achieved the number one spot in its first week, earning £2.5 million ($4.6 million) while playing on 397 screens.[97][98][99] The film stayed at the top for two more weeks, earning by then a total of over £9 million at the UK box office. It was featured on 412 screens at its widest domestic release.[99]

On 11 November 2005, the film debuted in the United States with an opening weekend of $2.9 million on 215 screens.[100] Two weeks later, it played on 1,299 screens and box office returns increased to $7.2 million; the film left cinemas the week of 24 February 2006 with a total US gross of $38,405,088.[4] Jack Foley, the president of distribution of Focus Features, the film's US distributor, attributed Pride & Prejudice's success in America to Austen's appeal to "the boomer market" and its status as a known "brand".[101]

Pride & Prejudice was released in an additional fifty-nine countries between September 2005 and May 2006 by United International Pictures.[98] With a worldwide gross of $121,147,947, it was the 72nd highest grossing film of 2005 in the US and was the 41st highest internationally.[4]

Home media

In the US and UK, Universal Studios Home Entertainment released the standard VHS and DVD in February 2006 for both widescreen and fullframe; attached bonus features included audio commentary by director Joe Wright, a look into Austen's life and the ending scene of Elizabeth and Darcy kissing.[68][4][102] On 13 November 2007, Universal released the deluxe edition DVD to coincide with the theatrical arrival of Wright's 2007 film Atonement. The deluxe edition included both widescreen and fullscreen features, the original soundtrack CD, a collectible book and booklet, as well as a number of special features not included in the original DVD.[103] In the US, a Blu-ray version of the film was released by Universal on 26 January 2010, which also contained bonus features.[104]

Reception

Pride & Prejudice was only the second film version after "the famed, but oddly flawed, black-and-white 1940 adaptation, starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier",[105] and until 2005, The Times considered the 1995 television adaptation "so dominant, so universally adored, [that] it has lingered in the public consciousness as a cinematic standard."[105] Wright's film consequently met with some scepticism from admirers of Austen, especially in relation to plot changes and casting choices.[106]"Any resemblance to scenes and characters created by Miss Austen is, of course, entirely coincidental," mocked The New Yorker's film critic.[107] Given Austen's characters were landed gentry, especially criticised was the re-imagining of the Bennetts as country bumpkins, lacking even the basics of table manners, and their home "a barnyard".[108]

Comparing six major adaptations of Pride and Prejudice in 2005, The Daily Mirror gave the only top marks of 9 out of 10 to the 1995 serial and the 2005 film, leaving the other adaptations behind with six or fewer points.[109] On the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a "certified fresh" approval rating of 86% based on reviews from 173 critics, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The website's consensus reads: "Sure, it's another adaptation of cinema's fave Jane Austen novel, but key performances and a modern filmmaking sensibility make this familiar period piece fresh and enjoyable."[110]Metacritic reported an average score of 82 out of 100, based on 37 reviews and classified the film as "universally acclaimed".[111]

Critics claimed the film's time constraints did not capture the depth and complexity of the television serials[18] and called Wright's adaptation "obviously [not as] daring or revisionist" as the serial.[112] JASNA president Joan Klingel Ray preferred the young age of Knightley and Macfadyen, saying that Jennifer Ehle had formerly been "a little too 'heavy' for the role."[113]Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, while praising Knightley for an outstanding performance "which lifts the whole movie", considered the casting of the leads "arguably a little more callow than Firth and Ehle." He does add that "Only a snob, a curmudgeon, or someone with necrophiliac loyalty to the 1995 BBC version with Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle could fail to enjoy [Knightley's] performance."[112] At the time, BBC film critic Stella Papamichael considered it Knightley's "best performance yet."[95] However, The Daily Telegraph critic thought Knightley's acting skills slight, in her view, "Someone who radiates little more than good-mannered perkiness", and that between her and Macfadyen there was "little spark".[114]

Critics were divided about Macfadyen's portrayal of Darcy, expressing pleasant surprise,[113][115] dislike for his lack of gradual emotional shift as in the novel,[113][116] and praise for his matching the insecure and sensitive personality of the book character better than Firth.[18]

Critics also drew attention to other aspects of the film. Writing for The Sydney Morning Herald, Sandra Hall criticised Wright's attention to realism for being "careless with the customs and conventions that were part of the fabric of Austen's world."[117] In another review, Time Out magazine lamented the absence of Austen's "brilliant sense of irony", remarking that the film's "romantic melodrama's played up at the expense of her razor-sharp wit."[116] More positively, Derek Elley of Variety magazine praised Wright and Moggach for "extracting the youthful essence" of the novel while also "providing a richly detailed setting" under Greenwood and Durran's supervision.[6] Equally pleased with the film was the San Francisco Chronicle's Ruthe Stein, who wrote that Wright made a "spectacular feature film debut" that is "creatively reimagined and sublimely entertaining".[118] Claudia Puig of USA Today called it "a stellar adaptation, bewitching the viewer completely and incandescently with an exquisite blend of emotion and wit."[119]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

Academy Awards[120] | Best Actress | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

Best Original Score | Dario Marianelli | Nominated | |

Best Art Direction | Sarah Greenwood, Katie Spencer | Nominated | |

Best Costume Design | Jacqueline Durran | Nominated | |

American Cinema Editors[121] | Best Edited Feature Film – Comedy or Musical | Paul Tothill | Nominated |

Boston Society of Film Critics[122] | Best New Filmmaker | Joe Wright | Won |

British Academy Film Awards[123][124] | Best British Film | Pride & Prejudice | Nominated |

Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Brenda Blethyn | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Newcomer | Joe Wright | Won | |

Best Adapted Screenplay | Deborah Moggach | Nominated | |

Best Costume Design | Jacqueline Durran | Nominated | |

Best Makeup & Hair | Fae Hammond | Nominated | |

Broadcast Film Critics Association[125] | Best Actress | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

Chicago Film Critics Association[126] | Best Actress | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Roman Osin | Nominated | |

Best Supporting Actor | Donald Sutherland | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Filmmaker | Joe Wright | Nominated | |

Empire Awards[127] | Best Actress | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

| Best British Film | Pride & Prejudice | Won | |

Best Director | Joe Wright | Nominated | |

Best Newcomer | Kelly Reilly | Won | |

European Film Awards[128] | Best Cinematographer | Roman Osin | Nominated |

Best Composer | Dario Marianelli | Nominated | |

Best Film | Joe Wright | Nominated | |

Golden Globe Awards[129] | Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

Best Film – Musical or Comedy | Pride & Prejudice | Nominated | |

London Film Critics' Circle[130] | British Actress of the Year | Keira Knightley | Nominated |

British Director of the Year | Joe Wright | Won | |

British Film of the Year | Pride & Prejudice | Nominated | |

| British Newcomer of the Year | Matthew Macfadyen | Nominated | |

| British Newcomer of the Year | Joe Wright | Nominated | |

| British Supporting Actor of the Year | Tom Hollander | Won | |

| British Supporting Actress of the Year | Brenda Blethyn | Nominated | |

| British Supporting Actress of the Year | Rosamund Pike | Nominated |

Impact and legacy

Wright's adaptation failed to have the same cultural impact as the 1995 serial and has since attracted sharply-divided opinions.[92][131][132] However, even three years after the release, Knightley was still associated with Elizabeth Bennet among a generation of young viewers who had not seen the 1995 production.[133] Given the varied opinions about the film, JASNA published an edited special issue of its online journal Persuasions On-Line in 2007 with the collaboration of nineteen Austen scholars from six countries; the intent was to foster discussion and stimulate scholarly analysis. JASNA had done this only once before, for the 1996 film Emma.[92][131][134]

Pride & Prejudice impacted later productions in the costume drama and heritage film genres. Literary critics protested that Wright's adaptation effectively "popularized Austen's celebrated romance and brought her novel to the screen as an easy visual read for an undemanding mainstream audience."[135] Carole Dole noted that the film's success "only made it more likely that future adaptations of Austen will feature, if not necessarily mud, then at least youthful and market-tested performers and youth-oriented filmmaking techniques balanced with the visual pleasures of the heritage film." She cited Anne Hathaway in the 2007 film Becoming Jane as an example.[5] Jessica Durgan added that Pride & Prejudice conceived a new hybrid genre by rejecting the visual cues of the heritage film, which attracted "youth and mainstream audiences without alienating the majority of heritage fans."[8]

Production of Pride & Prejudice began Wright's relationship with Working Title Films, the first of four collaborations.[136] Many members of the film's cast and crew joined Wright in his later directorial efforts. For his adaptation of Atonement, which he viewed as "a direct reaction to Pride & Prejudice",[137] Wright hired Knightley, Blethyn, Marianelli, Thibaudet, Greenwood, and Durran.[138]Atonement employed themes similar to Austen's, including the notion of a young writer living in "an isolated English country house" who "mixes up desires and fantasies, truths and fiction."[73] Wright's 2009 film The Soloist included Hollander, Malone, and Marianelli,[139][140][141] while Hollander was also featured in Hanna (2011).[142] Wright's 2012 adaptation of Anna Karenina features Knightley, Macfadyen, Marianelli, Durran, and Greenwood and is produced by Bevan, Eric Fellner, and Webster.[136]

On 11 December 2017, Netflix announced that a person from Chile watched the film 278 times during the entire year.[143] It was later reported that the person is a 51-year old woman, who declared herself as "obssesed" to the film and sees Elizabeth Bennet as "a feminist icon".[144]

See also

- Jane Austen in popular culture

- Janeite

- List of literary adaptations of Pride and Prejudice

Notes

^ Austen wrote a draft of First Impressions (later renamed Pride and Prejudice) between October 1796 and August 1797.[28]

^ Recent Austen adaptations included Mansfield Park (1999), Bridget Jones's Diary (2001), Pride & Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy (2003), and Bride and Prejudice (2004).[87]

References

^ "Pride & Prejudice (U)". United International Pictures. British Board of Film Classification. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab British Film Institute.

^ ab The Numbers.

^ abcd Box Office Mojo Profile.

^ abcdefgh Dole 2007.

^ abc Elley 2005.

^ ab Higson 2011, p. 170.

^ abcd Durgan 2007.

^ Troost 2007, p. 86.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrst Focus Features Production 2005.

^ Andrew 2011, p. 31.

^ Higson 2011, p. 166.

^ ab Cartmell 2010, p. 85.

^ abcdef Spunberg 2011.

^ abcdefghi Hanson 2005.

^ ab Wells 2007.

^ ab Dawtrey 2004.

^ abcde Holden 2005.

^ abcdef Hoggard 2005.

^ Higson 2011, p. 171.

^ abcde DeGennaro 2005.

^ abcdefghi Fetters.

^ abcd Haun 2005.

^ abcd Austen 2008.

^ Wright 2005, 10:00–10:40.

^ ab Hewitt 2005.

^ Wright 2005, 55:30–55:44.

^ Silvers & Olsen 2011, p. 191.

^ Cartmell 2010, p. 11.

^ ab Cartmell 2010, p. 86.

^ Woodworth 2007.

^ ab Rojas Weiss 2005.

^ Lee 2005.

^ ab Alberge 2004.

^ abcde The Daily Mail 2005.

^ ab Wright 2005, 4:10–4:35.

^ Hall 2010.

^ Sanderson, Challand & Graham 2010.

^ Roberts 2010.

^ Sutherland 2005, 3:10–3:20.

^ Cartmell 2010, p. 63.

^ Wright 2005, 1:00:05–1:00:15.

^ abcd Robey 2006.

^ Tandy 2007.

^ Wright 2005, 23:40–24:00.

^ Wright 2005, 7:30–7:40.

^ Wright 2005, 35:10–35:30.

^ Demory 2010, p. 134.

^ abc Focus Features Locations 2005.

^ Chan 2007.

^ Gymnich, Ruhl & Scheunemann 2010, p. 40.

^ Austen 2006, pp. 392–96.

^ ab Cartmell 2010, p. 89.

^ Knightley 2005, 1:25–1:30.

^ Whitlock 2010, p. 304.

^ Desowitz 2005.

^ Silvers & Olsen 2011, p. 194.

^ Wright 2005, 4:50–4:55.

^ BBC News 2004.

^ Whitlock 2010, p. 305.

^ McGhie 2005.

^ Wright 2005, 5:00–5:14, 11:00–11:30.

^ abc Goldwasser 2006.

^ ab O'Brien.

^ Ruhlmann.

^ Wright 2005, 1:00–1:20.

^ ab Gilligan 2011.

^ ab PRNewswire 2006.

^ Monaghan, Hudelet & Wiltshire 2009, p. 88.

^ Gymnich, Ruhl & Scheunemann 2010, pp. 40–41.

^ Higson 2011, pp. 172–73.

^ Wloszczyna 2005.

^ ab Brownstein 2011, pp. 53.

^ Dawson Edwards 2008, p. 1.

^ Working Title Films 2005d.

^ Austen 2006, pp. 403–05.

^ Demory 2010, p. 132.

^ Ailwood 2007.

^ abcd Stewart-Beer 2007.

^ ab Martin 2007.

^ Paquet-Deyris 2007.

^ abc Seeber 2007.

^ Palmer 2007.

^ Wright 2005, 6:40–6:55.

^ Wright 2005, 14:00–14:30.

^ Kaplan 2007.

^ Higson 2011, pp. 161–70.

^ Dawson Edwards 2008, p. 4.

^ Troost 2007, p. 87.

^ Higson 2011, p. 172.

^ Sadoff 2010, p. 87.

^ abc Camden 2007.

^ MTV 2005.

^ Working Title Films 2005a.

^ ab Papamichael 2005.

^ Working Title Films 2005b.

^ Working Title Films 2005c.

^ ab Box Office Mojo International Box Office.

^ ab UK Film Council.

^ Los Angeles Times 2005.

^ Gray 2005.

^ Carrier 2006.

^ PRNewswire 2007.

^ McCutcheon 2009.

^ ab Briscoe 2005.

^ Demory 2010, p. 129.

^ Lane, Anthony "Parent Traps", The New Yorker, 14 November 2005

^ Lane, Anthony "Parent Traps", The New Yorker, 14 November 2005

^ Edwards 2005.

^ Rotten Tomatoes.

^ Metacritic.

^ ab Bradshaw 2005.

^ abc Hastings 2005.

^ Sandhu, Sukhdev "A jolly romp to nowhere", The Daily Telegraph (London), 16 September 2005

^ Gleiberman 2005.

^ ab Time Out 2005.

^ Hall 2005.

^ Stein 2005.

^ Puig 2005.

^ Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

^ Soares 2006a.

^ Kimmel 2005.

^ British Academy of Film and Television Arts.

^ Working Title Films 2006.

^ Broadcast Film Critics Awards 2006.

^ Soares 2006b.

^ Empire Awards 2006.

^ Soares 2006c.

^ Hollywood Foreign Press Association 2005.

^ Barraclough 2005.

^ ab Camden & Ford 2007.

^ Wightman 2011.

^ Wells 2008, pp. 109–110.

^ Copeland & McMaster 2011, p. 257.

^ Sabine 2008.

^ ab Working Title Films 2011.

^ Wloszczyna 2007.

^ Wells 2008, p. 110.

^ Monger.

^ Bradshaw 2009.

^ Pham 2010.

^ McCarthy 2011.

^ Villa 2017.

^ Gutiérrez 2017.

Bibliography

Books

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Andrew, Dudley (2011). "The Economies of Adaptation". True to the Spirit: Film Adaptation and the Question of Fidelity. Colin MacCabe, Rick Warner, Kathleen Murray (editors). Oxford University Press. pp. 27–40. ISBN 0-19-537467-3.

Austen, Jane (2006). Jane Austen: Complete and Unabridged. Sarah S.G. Frantz (editor). Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-7607-7401-3.

Austen, Jane (2008). Pride and Prejudice: A Penguin Enhanced e-Book Classic. Vivian Jones, Tony Tanner, Juliette Wells (editors). Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-143951-3. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

Brownstein, Rachel M. (2011). Why Jane Austen?. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-15390-2.

Cartmell, Deborah (2010). Screen Adaptations: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice: A Close Study of the Relationship between Text and Film. A&C Black Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1-4081-0593-4.

Copeland, Edward; McMaster, Juliet (2011). The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-74650-7.

Dawson Edwards, Kyle (2008). Corporate Fictions: Film Adaptation and Authorship in the Classical Hollywood Era. ProQuest Information and Learning Company. ISBN 0-549-38632-7.

Demory, Pamela (2010). "Jane Austen and the Chick Flick in the Twenty-first Century". Adaptation Studies: New Approaches. Christa Albrecht-Crane, Dennis Cutchins (editors). Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp. pp. 121–149. ISBN 0-8386-4262-4.

Gymnich, Marion; Ruhl, Kathrin; Scheunemann, Klaus (2010). "Revisiting the Classical Romance: Pride and Prejudice, Bridget Jones's Diary and Bride and Prejudice". Gendered (Re)Visions: Constructions of Gender in Audiovisual Media. Bonn University Press. pp. 23–44. ISBN 3-89971-662-0.

Higson, Andrew (2011). Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking Since the 1990s. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84885-454-4.

Monaghan, David; Hudelet, Ariane; Wiltshire, John (2009). The Cinematic Jane Austen: Essays on the Filmic Sensibility of the Novels. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-7864-3506-2.

Silvers, Josh; Olsen, Toby D. (2011). "Pride and Prejudice: Establishing Historical Connections Among the Arts". Conjuring the Real: The Role of Architecture in Eighteenth- And Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Rumiko Handa, James Potter (editors), Iain Borden (foreword). University of Nebraska Press. pp. 191–214. ISBN 0-8032-1743-9.

Troost, Linda V. (2007). "The Nineteenth-Century Novel on Film: Jane Austen". The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen. Deborah Cartmell, Imelda Whelehan (editors). Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–89. ISBN 0-521-61486-4.

Whitlock, Cathy (2010). Designs on Film: A Century of Hollywood Art Direction. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-088122-4.

Essays and journals

Ailwood, Sarah (Summer 2007). "What Are Men to Rocks and Mountains?' Romanticism in Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice'". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

Camden, Jen (Summer 2007). "Sex and the Scullery: The New Pride & Prejudice". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

Camden, Jen; Ford, Susan Allen (Summer 2007). "Something new to be observed ... for ever". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

Chan, Mary (Summer 2007). "Location, Location, Location: The Spaces of Pride & Prejudice". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

Dole, Carole (Summer 2007). "Jane Austen and Mud: Pride & Prejudice (2005), British Realism and the Heritage Film". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

Durgan, Jessica (Summer 2007). "Framing Heritage: The Role of Cinematography in Pride & Prejudice". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

Gilligan, Kathleen E. (2011). "Jane Austen's Unnamed Character: Exploring Nature in Pride and Prejudice (2005)". Student Pulse. 3 (12). Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

Kaplan, Laurie (Summer 2007). "Inside Out/Outside In: Pride & Prejudice on Film 2005". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

Martin, Lydia (Summer 2007). "Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice: From Classicism to Romanticism". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

Palmer, Sally B. (Summer 2007). "Little Women at Longbourn: The Re-Wrighting of Pride and Prejudice". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

Paquet-Deyris, Anne-Marie (Summer 2007). "Staging intimacy and interiority in Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice (2005)". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

Sabine, Maureen (Fall 2008). "With My Body I Thee Worship: Joe Wright's Erotic Vision in Pride & Prejudice (2005)". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 20. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

Sadoff, Dianne F. (Spring 2010). "Marketing Jane Austen at the Megaplex". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. 43 (1): 83–92. doi:10.1215/00295132-2009-067.

Seeber, Barbara K. (Summer 2007). "A Bennet Utopia: Adapting the Father in Pride and Prejudice". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

Stewart-Beer, Catherine (Summer 2007). "Style over Substance? Pride & Prejudice (2005) Proves Itself a Film for Our Time". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

Tandy, Ann M. (Summer 2007). "'Just What a Young Man Ought to Be': The 2005 Pride & Prejudice and Transitional Ideas of Gentility". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

Wells, Juliette (Summer 2007). "A Fearsome Thing to Behold'? The Accomplished Woman in Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice'". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

Wells, Juliette (2008). "Shades of Austen in Ian McEwan's Atonement" (PDF). New Directions in Austen Studies. 30 (2): 101–112. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

Woodworth, Megan (Summer 2007). "'I am a gentleman's daughter'? Translating Class from Austen's Page to the Twenty-first-century Screen". Persuasions On-Line. Jane Austen Society of North America. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

Interviews

"Interview with the cast of Pride & Prejudice". Daily Mail. 9 September 2005. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

DeGennaro, Alexa (12 November 2005). "Interview with New Pride and Prejudice Director Joe Wright". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

Fetters, Sara Michelle. "It's Austen All Over Again". MovieFreak.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

Goldwasser, Dan (March 2006). "Interview – Dario Marianelli". Soundtrack.net. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

Hanson, Briony; David Benedict (13 September 2005). "A masterclass with Deborah Moggach & Joe Wright". The Script Factory. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

Hewitt, Chris (9 November 2005). "Unlikely Director Brought New Approach to Pride & Prejudice". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

(subscription required)

Hoggard, Liz (10 September 2005). "Meet the puppet master". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

Lee, Alana (September 2005). "BBC – Movies – interview – Keira Knightley". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

Robey, Tim (3 February 2006). "How I undressed Mr Darcy". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

Spunberg, Adam (1 April 2011). "Scripting Pride & Prejudice with Deborah Moggach". Picktainment.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

Newspaper and magazine articles

Alberge, Dalya (11 June 2004). "Hunt for Darcy nets star of TV spy drama". The Times. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

(subscription required)

"Austen story filmed at old house". BBC News. 19 July 2004. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

Barraclough, Leo (21 December 2005). "Pride of crix kudos". Variety. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

Bradshaw, Peter (16 September 2005). "Pride & Prejudice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

Bradshaw, Peter (25 September 2009). "The Soloist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

Briscoe, Joanna (31 July 2005). "A costume drama with muddy hems". The Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

Dawtrey, Adam (19 January 2004). "London Eye". Variety. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

(subscription required)

Edwards, David (9 September 2005). "Pride and Passion". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

Elley, Derek (11 September 2005). "Pride & Prejudice (U.K.–U.S.)". Variety. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

Gleiberman, Owen (9 November 2005). "Pride & Prejudice (2005)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

Hall, Sandra (20 October 2005). "Pride and Prejudice". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

Hastings, Chris (8 August 2005). "Colin Firth was born to play Mr Darcy. So can anyone else shine in the lead role?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

Haun, Harry (1 November 2005). "Austentatious Debut". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

Holden, Stephen (11 November 2005). "Marrying Off Those Bennet Sisters Again, but This Time Elizabeth Is a Looker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

Kimmel, Daniel M. (11 December 2005). "Boston film crix hail Brokeback, Capote". Variety. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

McGhie, Caroline (24 August 2005). "A house in want of a fortune". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

Papamichael, Stella (16 September 2005). "Pride & Prejudice (2005)". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

Pham, Alex (24 July 2010). "COMIC-CON 2010: Zack Snyder's Sucker Punch goes for grrrl power". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

Puig, Claudia (10 November 2005). "This Pride does Austen proud". USA Today. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

Roberts, Laura (16 December 2010). "British actresses who made their name starring in Jane Austen adaptations". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

Rojas Weiss, Sabrina (11 November 2005). "Keira Knightley Has Austen Power". TV Guide. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

Sanderson, Elizabeth; Challand, Christine; Graham, Caroline (3 May 2010). "The miseducation of Carey Mulligan: How did actress become our hottest leading lady?". Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

Stein, Ruthe (11 November 2005). "Luscious new Pride & Prejudice updates the mating game". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice (2005)". Time Out. 14 September 2005. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

Wloszczyna, Susan (13 November 2005). "It was the best kiss, it was the worst in Pride & Prejudice". USA Today. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

Wloszczyna, Susan (6 September 2007). "Returning directors feel the warmth in fest spotlight". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

Online

"Nominees & Winners for the 78th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"Awards database". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"Pride and Prejudice (2005) – International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"Pride and Prejudice (2005)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

"Pride and Prejudice (2005)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

"The 11th Critics' Choice Movie Awards Winners and Nominees". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Carrier, Steven (24 January 2006). "Pride & Prejudice (UK – DVD R2/5)". DVDactive. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

Desowitz, Bill (22 September 2005). "Double Negative Does VFX for Pride & Prejudice". Animation World Network. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

"Sony Ericsson Empire Awards 2006". Empire. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Gray, Brandon (14 November 2005). "Pride and Prejudice Impresses in Limited Bow". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

"63rd Golden Globe Awards Nominations". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Hall, Katy (18 March 2010). "Carey Mulligan Gets An Education In Movie Stardom". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

"Weekend box office". Los Angeles Times. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

McCarthy, Todd (30 March 2011). "Hanna: Movie Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

McCutcheon, David (21 December 2009). "Pride Finds Prejudice". IGN. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice (2005 film): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

Monger, James Christopher. " The Soloist [Music from the Motion Picture]". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

"Keira Knightley Hits The Red Carpet". MTV. 10 October 2005. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

O'Brien, Jon. "Pride & Prejudice [Original Score]". AllMusic. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

"Pride and Prejudice (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

Ruhlmann, William. "Pride & Prejudice [Original Score] Album Reviews". Billboard. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

Soares, Andre (19 February 2006). "American Cinema Editors Awards 2006". Alt Film Guide. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

Soares, Andre (9 January 2006). "Chicago Film Critics Awards 2005". Alt Film Guide. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

Soares, Andre (2 December 2006). "European Film Awards 2006". Alt Film Guide. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

"Pride and Prejudice". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

"UK Box Office: 2005". UK Film Council. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

Wightman, Catriona (12 November 2011). "Pride and Prejudice: Tube Talk Gold". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

Villa, Bernardita (11 December 2017). "Las series más vistas por los chilenos en Netflix" [The most watched TV series by chileans in Netflix] (in Spanish). Bio-Bio. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

Gutiérrez, Catalina (14 December 2017). ""Me gusta Orgullo y Prejuicio porque es feminista"" ["I like Pride & Prejudice because is a feminist film"] (in Spanish). Women Talk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

Press releases

"Pride & Prejudice: The Locations" (Press release). Focus Features. 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice: The Production" (Press release). Focus Features. 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

"Nominated for Four Academy Awards(R)* Including Best Actress Keira Knightley Universal Studios Home Entertainment Is Proud to Announce the DVD Release of Jane Austen's Ultimate Romance Pride & Prejudice" (Press release). PR Newswire. 31 January 2006. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"From Universal Studios Home Entertainment: Pride & Prejudice 2 Disc Deluxe Gift Set" (Press release). PR Newswire. 20 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice gala screening in Toronto" (Press release). Working Title Films. 29 July 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice released this weekend" (Press release). Working Title Films. 15 September 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice is a number 1 hit" (Press release). Working Title Films. 19 September 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

"Pride & Prejudice – US ending now on release in UK" (Press release). Working Title Films. 25 November 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.