Orbital period

Orbital period

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The orbital period is the time a given astronomical object takes to complete one orbit around another object, and applies in astronomy usually to planets or asteroids orbiting the Sun, moons orbiting planets, exoplanets orbiting other stars, or binary stars.

For objects in the Solar System, this is often referred to as the sidereal period, determined by a 360° revolution of one celestial body around another, e.g. the Earth orbiting the Sun. The name sidereal is added as it implies that the object returns to the same position relative to the fixed stars projected in the sky. When describing orbits of binary stars, the orbital period is usually referred to as just the period. For example, Jupiter has a sidereal period of 11.86 years while the main binary star Alpha Centauri AB has a period of about 79.91 years.

Another important orbital period definition can refer to the repeated cycles for celestial bodies as observed from the Earth's surface. An example is the so-called synodic period, applying to the elapsed time where planets return to the same kind of phenomena or location. For example, when any planet returns between its consecutive observed conjunctions with or oppositions to the Sun. For example, Jupiter has a synodic period of 398.8 days from Earth; thus, Jupiter's opposition occurs once roughly every 13 months.

Periods in astronomy are conveniently expressed in various units of time, often in hours, days, or years. They can be also defined under different specific astronomical definitions that are mostly caused by small complex eternal gravitational influences by other celestial objects. Such variations also include the true placement of the centre of gravity between two astronomical bodies (barycenter), perturbations by other planets or bodies, orbital resonance, general relativity, etc. Most are investigated by detailed complex astronomical theories using celestial mechanics using precise positional observations of celestial objects via astrometry.

Contents

1 Other periods related to the orbital period

2 Small body orbiting a central body

3 Orbital period as a function of central body's density

4 Two bodies orbiting each other

5 Synodic period

6 Examples of sidereal and synodic periods

6.1 Synodic periods relative to other planets

7 Binary stars

8 See also

9 Notes

10 Bibliography

11 External links

[edit]

There are many periods related to the orbits of objects, each of which are often used in the various fields of astronomy and astrophysics. Examples of some of the common ones include the following:

- The sidereal period is the amount of time that it takes an object to make a full orbit, relative to the stars. This is the orbital period in an inertial (non-rotating) frame of reference.

- The synodic period is the amount of time that it takes for an object to reappear at the same point in relation to two or more other objects (e.g. the Moon's phase and its position relative to the Sun and Earth repeats every 29.5 day synodic period, longer than its 27.3 day orbit around the Earth, due to the motion of the Earth about the Sun). The time between two successive oppositions or conjunctions is also an example of the synodic period. For the planets in the solar system, the synodic period (with respect to Earth) differs from the sidereal period due to the Earth's orbiting around the Sun.

- The draconitic period (also draconic period or nodal period), is the time that elapses between two passages of the object through its ascending node, the point of its orbit where it crosses the ecliptic from the southern to the northern hemisphere. This period differs from the sidereal period because both the orbital plane of the object and the plane of the ecliptic precess with respect to the fixed stars, so their intersection, the line of nodes, also precesses with respect to the fixed stars. Although the plane of the ecliptic is often held fixed at the position it occupied at a specific epoch, the orbital plane of the object still precesses causing the draconitic period to differ from the sidereal period.[1]

- The anomalistic period is the time that elapses between two passages of an object at its periapsis (in the case of the planets in the Solar System, called the perihelion), the point of its closest approach to the attracting body. It differs from the sidereal period because the object's semi-major axis typically advances slowly.

- Also, the tropical period of Earth (a tropical year) is the interval between two alignments of its rotational axis with the Sun, also viewed as two passages of the object at a right ascension of 0 hr. One Earth year is slightly shorter than the period for the Sun to complete one circuit along the ecliptic (a sidereal year) because the inclined axis and equatorial plane slowly precess (rotate with respect to reference stars), realigning with the Sun before the orbit completes. This cycle of axial precession for Earth, known as precession of the equinoxes, recurs roughly every 25,770 years.[citation needed]

Small body orbiting a central body[edit]

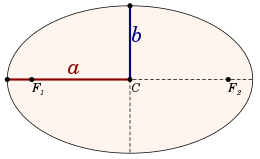

The semi-major axis (a) and semi-minor axis (b) of an ellipse

According to Kepler's Third Law, the orbital period T (in seconds) of two point masses orbiting each other in a circular or elliptic orbit is:[2]

- T=2πa3μ{displaystyle T=2pi {sqrt {frac {a^{3}}{mu }}}}

where:

a is the orbit's semi-major axis

μ = GM is the standard gravitational parameter

G is the gravitational constant,

M is the mass of the more massive body.

For all ellipses with a given semi-major axis the orbital period is the same, regardless of eccentricity.

Inversely, for calculating the distance where a body has to orbit in order to have a given orbital period:

- a=GMT24π23{displaystyle a={sqrt[{3}]{frac {GMT^{2}}{4pi ^{2}}}}}

where:

a is the orbit's semi-major axis in meters,

G is the gravitational constant,

M is the mass of the more massive body,

T is the orbital period in seconds.

For instance, for completing an orbit every 24 hours around a mass of 100 kg, a small body has to orbit at a distance of 1.08 meters from its center of mass.

Orbital period as a function of central body's density[edit]

When a very small body is in a circular orbit barely above the surface of a sphere of any radius and mean density ρ (in kg/m3), the above equation simplifies to (since M = Vρ = 4/3πa3ρ)[3]>:

- T=3πGρ{displaystyle T={sqrt {frac {3pi }{Grho }}}}

So, for the Earth as the central body (or any other spherically symmetric body with the same mean density, about 5,515 kg/m3)[4] we get:

T = 1.41 hours

and for a body made of water (ρ ≈ 1,000 kg/m3)[5]

T = 3.30 hours

Thus, as an alternative for using a very small number like G, the strength of universal gravity can be described using some reference material, like water: the orbital period for an orbit just above the surface of a spherical body of water is 3 hours and 18 minutes. Conversely, this can be used as a kind of "universal" unit of time if we have a unit of mass, a unit of length and a unit of density.

Two bodies orbiting each other[edit]

In celestial mechanics, when both orbiting bodies' masses have to be taken into account, the orbital period T can be calculated as follows:[6]

- T=2πa3G(M1+M2){displaystyle T=2pi {sqrt {frac {a^{3}}{Gleft(M_{1}+M_{2}right)}}}}

where:

a is the sum of the semi-major axes of the ellipses in which the centers of the bodies move, or equivalently, the semi-major axis of the ellipse in which one body moves, in the frame of reference with the other body at the origin (which is equal to their constant separation for circular orbits),

M1 + M2 is the sum of the masses of the two bodies,

G is the gravitational constant.

Note that the orbital period is independent of size: for a scale model it would be the same, when densities are the same (see also Orbit#Scaling in gravity).[citation needed]

In a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory, the motion is not periodic, and the duration of the full trajectory is infinite.

Synodic period[edit]

There are observable characteristics of two bodies which orbit a third body in different orbits, and thus have different orbital periods. This is known as their synodic period; it is the time between conjunctions, and since it is observable from either the first or the second body, the two synodic periods will be different, depending from which celestial body you are observing.

An example of this related period description is the repeated cycles for celestial bodies as observed from the Earth's surface, the so-called synodic period, applying to the elapsed time where planets return to the same kind of phenomena or location. For example, when any planet returns between its consecutive observed conjunctions with or oppositions to the Sun. For example, Jupiter has a synodic period of 398.8 days from Earth; thus, Jupiter's opposition occurs once roughly every 13 months.

If the orbital periods of the two bodies around the third are called P1 and P2, so that P1 < P2, their synodic period is given by:[citation needed]

- 1Psyn=1P1−1P2{displaystyle {frac {1}{P_{mathrm {syn} }}}={frac {1}{P_{1}}}-{frac {1}{P_{2}}}}

Examples of sidereal and synodic periods[edit]

Table of synodic periods in the Solar System, relative to Earth:[citation needed]

| Object | Sidereal period (yr) | Synodic period (yr) | Synodic period (d)[7] |

|---|---|---|---|

Mercury | 0.240846 (87.9691 days) | 0.317 | 115.88 |

Venus | 0.615 (225 days) | 1.599 | 583.9 |

Earth | 1 (365.25636 solar days) | — | — |

Moon | 0.0748 (27.32 days) | 0.0809 | 29.5306 |

99942 Apophis (near-Earth asteroid) | 0.886 | 7.769 | 2,837.6 |

Mars | 1.881 | 2.135 | 779.9 |

4 Vesta | 3.629 | 1.380 | 504.0 |

1 Ceres | 4.600 | 1.278 | 466.7 |

10 Hygiea | 5.557 | 1.219 | 445.4 |

Jupiter | 11.86 | 1.092 | 398.9 |

Saturn | 29.46 | 1.035 | 378.1 |

2060 Chiron | 50.42 | 1.020 | 372.6 |

Uranus | 84.01 | 1.012 | 369.7 |

Neptune | 164.8 | 1.006 | 367.5 |

134340 Pluto | 248.1 | 1.004 | 366.7 |

50000 Quaoar | 287.5 | 1.003 | 366.5 |

136199 Eris | 557 | 1.002 | 365.9 |

90377 Sedna | 12050 | 1.00001 | 365.1[citation needed] |

In the case of a planet's moon, the synodic period usually means the Sun-synodic period, namely, the time it takes the moon to complete its illumination phases, completing the solar phases for an astronomer on the planet's surface. The Earth's motion does not determine this value for other planets because an Earth observer is not orbited by the moons in question. For example, Deimos's synodic period is 1.2648 days, 0.18% longer than Deimos's sidereal period of 1.2624 d.[citation needed]

Synodic periods relative to other planets[edit]

The concept of synodic period does not just apply to the Earth, but also to other planets as well, and the formula for computation is the same as the one given above. Here is a table which lists the synodic periods of some planets relative to each other:

| Relative to | Jupiter | Saturn | Chiron | Uranus | Neptune | Pluto | Quaoar | Eris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sol | 11.86 | 29.46 | 50.42 | 84.01 | 164.8 | 248.1 | 287.5 | 557.0 |

Jupiter | 19.85 | 15.51 | 13.81 | 12.78 | 12.46 | 12.37 | 12.12 | |

Saturn | 70.87 | 45.37 | 35.87 | 33.43 | 32.82 | 31.11 | ||

2060 Chiron | 126.1 | 72.65 | 63.28 | 61.14 | 55.44 | |||

Uranus | 171.4 | 127.0 | 118.7 | 98.93 | ||||

Neptune | 490.8 | 386.1 | 234.0 | |||||

134340 Pluto | 1810.4 | 447.4 | ||||||

50000 Quaoar | 594.2 |

Binary stars[edit]

| Binary star | Orbital period |

|---|---|

AM Canum Venaticorum | 17.146 minutes |

Beta Lyrae AB | 12.9075 days |

Alpha Centauri AB | 79.91 years |

Proxima Centauri – Alpha Centauri AB | 500,000 years or more |

See also[edit]

- Geosynchronous orbit derivation

Rotation period – time that it takes to complete one revolution around its axis of rotation- Sidereal time

- Sidereal year

- Opposition (astronomy)

- List of periodic comets

Notes[edit]

^ Oliver Montenbruck, Eberhard Gill. Satellite Orbits: Models, Methods, and Applications. p. 50. Retrieved 1 June 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Bate, Mueller and White (1971), p. 33.

^ How do you calculate the density of a sphere?, quora.com

^ Density of the Earth, wolframalpha.com

^ Density of water, wolframalpha.com

^ Bradley W. Carroll, Dale A. Ostlie. An introduction to modern astrophysics. 2nd edition. Pearson 2007.

^ "Questions and Answers - Sten's Space Blog". www.astronomycafe.net.

Bibliography[edit]

Bate, Roger B.; Mueller, Donald D.; White, Jerry E. (1971), Fundamentals of Astrodynamics, Dover

External links[edit]

| Look up synodic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Categories:

- Time in astronomy

- Orbits

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.372","walltime":"0.868","ppvisitednodes":{"value":2001,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":68859,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":3301,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":11,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":6,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":15006,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":0,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 547.352 1 -total"," 25.30% 138.478 1 Template:Reflist"," 21.77% 119.148 6 Template:Citation_needed"," 20.24% 110.782 6 Template:Fix"," 18.27% 99.977 3 Template:Navbox"," 15.94% 87.243 1 Template:Orbits"," 14.25% 77.971 6 Template:Delink"," 14.16% 77.505 1 Template:Cite_book"," 10.48% 57.376 1 Template:Short_description"," 10.11% 55.319 1 Template:Pagetype"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.169","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":4061689,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1321","timestamp":"20181010145952","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":93,"wgHostname":"mw1263"});});

![{displaystyle a={sqrt[{3}]{frac {GMT^{2}}{4pi ^{2}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acc0794d19344d83b82ba93518c68a0fccd0b31b)