Caravaggio

Caravaggio | |

|---|---|

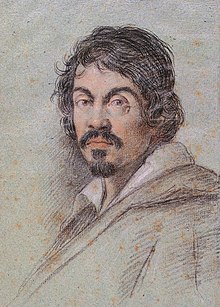

Chalk portrait of Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni, circa 1621. | |

| Born | Michelangelo Merisi or Amerighi 29 September 1571 Milan, Duchy of Milan, Spanish Empire[1] |

| Died | 18 July 1610(1610-07-18) (aged 38) Porto Ercole, State of the Presidi, Spanish Empire |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | See Chronology of works by Caravaggio |

| Movement | Baroque |

| Patron(s) | Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte Alof de Wignacourt |

Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio (/ˌkærəˈvædʒioʊ/, US: /-ˈvɑːdʒ-/, Italian pronunciation: [mikeˈlandʒelo meˈriːzi da (k)karaˈvaddʒo]; 28 September 1571[2] – 18 July 1610) was an Italian painter active in Rome, Naples, Malta, and Sicily from the early 1590s to 1610. His paintings combine a realistic observation of the human state, both physical and emotional, with a dramatic use of lighting, which had a formative influence on Baroque painting.[3][4][5]

Caravaggio employed close physical observation with a dramatic use of chiaroscuro that came to be known as tenebrism. He made the technique a dominant stylistic element, darkening shadows and transfixing subjects in bright shafts of light. Caravaggio vividly expressed crucial moments and scenes, often featuring violent struggles, torture and death. He worked rapidly, with live models, preferring to forgo drawings and work directly onto the canvas. His influence on the new Baroque style that emerged from Mannerism was profound. It can be seen directly or indirectly in the work of Peter Paul Rubens, Jusepe de Ribera, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and Rembrandt, and artists in the following generation heavily under his influence were called the "Caravaggisti" or "Caravagesques", as well as tenebrists or tenebrosi ("shadowists").

Caravaggio trained as a painter in Milan before moving in his twenties to Rome. He developed a considerable name as an artist, and as a violent, touchy and provocative man. A brawl led to a death sentence for murder and forced him to flee to Naples. There he again established himself as one of the most prominent Italian painters of his generation. He traveled in 1607 to Malta and on to Sicily, and pursued a papal pardon for his sentence. In 1609 he returned to Naples, where he was involved in a violent clash; his face was disfigured and rumours of his death circulated. Questions about his mental state arose from his erratic and bizarre behavior. He died in 1610 under uncertain circumstances while on his way from Naples to Rome. Reports stated that he died of a fever, but suggestions have been made that he was murdered or that he died of lead poisoning.

Caravaggio's innovations inspired Baroque painting, but the Baroque incorporated the drama of his chiaroscuro without the psychological realism. The style evolved and fashions changed, and Caravaggio fell out of favor. In the 20th century interest in his work revived, and his importance to the development of Western art was reevaluated. The 20th-century art historian André Berne-Joffroy stated, "What begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting."[6]

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Early life (1571–1592)

1.2 Beginnings in Rome (1592/95–1600)

1.3 "Most famous painter in Rome" (1600–1606)

1.4 A crime too many (1606)

1.5 Exile and death (1606–1610)

1.5.1 Naples

1.5.2 Malta

1.5.3 Sicily

1.5.4 Return to Naples

1.6 Death

1.7 Sexuality

2 As an artist

2.1 The birth of Baroque

2.2 The Caravaggisti

2.3 Death and rebirth of a reputation

2.4 Epitaph

3 Oeuvre

4 Art theft

5 See also

6 Footnotes

7 References

7.1 Primary sources

7.2 Secondary sources

8 External links

Biography

Early life (1571–1592)

Basket of Fruit, c. 1595–1596, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi or Amerighi) was born in Milan, where his father, Fermo (Fermo Merixio), was a household administrator and architect-decorator to the Marchese of Caravaggio, a town not far from the city of Bergamo.[7] In 1576 the family moved to Caravaggio (Caravaggius) to escape a plague that ravaged Milan, and Caravaggio's father and grandfather both died there on the same day in 1577.[8][9] It is assumed that the artist grew up in Caravaggio, but his family kept up connections with the Sforzas and with the powerful Colonna family, who were allied by marriage with the Sforzas and destined to play a major role later in Caravaggio's life.

Caravaggio's mother died in 1584, the same year he began his four-year apprenticeship to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian. Caravaggio appears to have stayed in the Milan-Caravaggio area after his apprenticeship ended, but it is possible that he visited Venice and saw the works of Giorgione, whom Federico Zuccari later accused him of imitating, and Titian.[10] He would also have become familiar with the art treasures of Milan, including Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, and with the regional Lombard art, a style that valued simplicity and attention to naturalistic detail and was closer to the naturalism of Germany than to the stylised formality and grandeur of Roman Mannerism.[11]

Beginnings in Rome (1592/95–1600)

Following his initial training under Simone Peterzano, in 1592 Caravaggio left Milan for Rome, in flight after "certain quarrels" and the wounding of a police officer. The young artist arrived in Rome "naked and extremely needy ... without fixed address and without provision ... short of money."[12] During this period he stayed with the miserly Pandolfo Pucci, known as "monnsignor Insalata".[13] A few months later he was performing hack-work for the highly successful Giuseppe Cesari, Pope Clement VIII's favourite artist, "painting flowers and fruit"[14] in his factory-like workshop.

In Rome there was demand for paintings to fill the many huge new churches and palazzos being built at the time. It was also a period when the Church was searching for a stylistic alternative to Mannerism in religious art that was tasked to counter the threat of Protestantism.[15] Caravaggio's innovation was a radical naturalism that combined close physical observation with a dramatic, even theatrical, use of chiaroscuro that came to be known as tenebrism (the shift from light to dark with little intermediate value).

The Musicians, 1595–1596, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Known works from this period include a small Boy Peeling a Fruit (his earliest known painting), a Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and the Young Sick Bacchus, supposedly a self-portrait done during convalescence from a serious illness that ended his employment with Cesari. All three demonstrate the physical particularity for which Caravaggio was to become renowned: the fruit-basket-boy's produce has been analysed by a professor of horticulture, who was able to identify individual cultivars right down to "... a large fig leaf with a prominent fungal scorch lesion resembling anthracnose (Glomerella cingulata)."[16]

Caravaggio left Cesari, determined to make his own way after a heated argument.[17] At this point he forged some extremely important friendships, with the painter Prospero Orsi, the architect Onorio Longhi, and the sixteen-year-old Sicilian artist Mario Minniti. Orsi, established in the profession, introduced him to influential collectors; Longhi, more balefully, introduced him to the world of Roman street-brawls.[18] Minniti served Caravaggio as a model and, years later, would be instrumental in helping him to obtain important commissions in Sicily. Ostensibly, the first archival reference to Caravaggio in a contemporary document from Rome is the listing of his name, with that of Prospero Orsi as his partner, as an 'assistante' in a procession in October 1594 in honour of St. Luke.[19] The earliest informative account of his life in the city is a court transcript dated 11 July 1597, when Caravaggio and Prospero Orsi were witnesses to a crime near San Luigi de' Francesi.[20]

An early published notice on Caravaggio, dating from 1604 and describing his lifestyle three years previously, recounts that "after a fortnight's work he will swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side and a servant following him, from one ball-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, so that it is most awkward to get along with him."[21] In 1606 he killed a young man in a brawl, possibly unintentionally, and fled from Rome with a death sentence hanging over him.

Judith Beheading Holofernes 1599–1602, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy (c. 1595)

The Fortune Teller, his first composition with more than one figure, shows a boy, likely Minniti, having his palm read by a gypsy girl, who is stealthily removing his ring as she strokes his hand. The theme was quite new for Rome, and proved immensely influential over the next century and beyond. This, however, was in the future: at the time, Caravaggio sold it for practically nothing. The Cardsharps – showing another naïve youth of privilege falling the victim of card cheats – is even more psychologically complex, and perhaps Caravaggio's first true masterpiece. Like The Fortune Teller, it was immensely popular, and over 50 copies survive. More importantly, it attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. For Del Monte and his wealthy art-loving circle, Caravaggio executed a number of intimate chamber-pieces – The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard – featuring Minniti and other adolescent models.

Caravaggio's first paintings on religious themes returned to realism, and the emergence of remarkable spirituality. The first of these was the Penitent Magdalene, showing Mary Magdalene at the moment when she has turned from her life as a courtesan and sits weeping on the floor, her jewels scattered around her. "It seemed not a religious painting at all ... a girl sitting on a low wooden stool drying her hair ... Where was the repentance ... suffering ... promise of salvation?"[22] It was understated, in the Lombard manner, not histrionic in the Roman manner of the time. It was followed by others in the same style: Saint Catherine; Martha and Mary Magdalene; Judith Beheading Holofernes; a Sacrifice of Isaac; a Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy; and a Rest on the Flight into Egypt. These works, while viewed by a comparatively limited circle, increased Caravaggio's fame with both connoisseurs and his fellow artists. But a true reputation would depend on public commissions, and for these it was necessary to look to the Church.

Already evident was the intense realism or naturalism for which Caravaggio is now famous. He preferred to paint his subjects as the eye sees them, with all their natural flaws and defects instead of as idealised creations. This allowed a full display of his virtuosic talents. This shift from accepted standard practice and the classical idealism of Michelangelo was very controversial at the time. Caravaggio also dispensed with the lengthy preparations traditional in central Italy at the time. Instead, he preferred the Venetian practice of working in oils directly from the subject – half-length figures and still life. Supper at Emmaus, from c. 1600–1601, is a characteristic work of this period demonstrating his virtuoso talent.

"Most famous painter in Rome" (1600–1606)

In 1599, presumably through the influence of Del Monte, Caravaggio was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The two works making up the commission, the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and Calling of Saint Matthew, delivered in 1600, were an immediate sensation. Thereafter he never lacked commissions or patrons.

The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600), Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome. Without recourse to flying angels, parting clouds or other artifice, Caravaggio portrays the instant conversion of St Matthew, the moment on which his destiny will turn, by means of a beam of light and the pointing finger of Jesus.

Caravaggio's tenebrism (a heightened chiaroscuro) brought high drama to his subjects, while his acutely observed realism brought a new level of emotional intensity. Opinion among his artist peers was polarized. Some denounced him for various perceived failings, notably his insistence on painting from life, without drawings, but for the most part he was hailed as a great artistic visionary: "The painters then in Rome were greatly taken by this novelty, and the young ones particularly gathered around him, praised him as the unique imitator of nature, and looked on his work as miracles."[23]

Caravaggio went on to secure a string of prestigious commissions for religious works featuring violent struggles, grotesque decapitations, torture and death, most notable and most technically masterful among them The Taking of Christ of circa 1602 for the Mattei Family, recently rediscovered in Ireland after two centuries.[24] For the most part each new painting increased his fame, but a few were rejected by the various bodies for whom they were intended, at least in their original forms, and had to be re-painted or find new buyers. The essence of the problem was that while Caravaggio's dramatic intensity was appreciated, his realism was seen by some as unacceptably vulgar.[25]

His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, featuring the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs attended by a lightly clad over-familiar boy-angel, was rejected and a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew. Similarly, The Conversion of Saint Paul was rejected, and while another version of the same subject, the Conversion on the Way to Damascus, was accepted, it featured the saint's horse's haunches far more prominently than the saint himself, prompting this exchange between the artist and an exasperated official of Santa Maria del Popolo: "Why have you put a horse in the middle, and Saint Paul on the ground?" "Because!" "Is the horse God?" "No, but he stands in God's light!"[26]

Death of the Virgin, 1601–1606, Louvre, Paris

Other works included Entombment, the Madonna di Loreto (Madonna of the Pilgrims), the Grooms' Madonna, and the Death of the Virgin. The history of these last two paintings illustrates the reception given to some of Caravaggio's art, and the times in which he lived. The Grooms' Madonna, also known as Madonna dei palafrenieri, painted for a small altar in Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, remained there for just two days, and was then taken off. A cardinal's secretary wrote: "In this painting there are but vulgarity, sacrilege, impiousness and disgust...One would say it is a work made by a painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God, from His adoration, and from any good thought..."

Amor Vincit Omnia, 1601–1602, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Caravaggio shows Cupid prevailing over all human endeavors: war, music, science, government.

The Death of the Virgin, commissioned in 1601 by a wealthy jurist for his private chapel in the new Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala, was rejected by the Carmelites in 1606. Caravaggio's contemporary Giulio Mancini records that it was rejected because Caravaggio had used a well-known prostitute as his model for the Virgin.[27]Giovanni Baglione, another contemporary, tells us it was due to Mary's bare legs[28] —a matter of decorum in either case. Caravaggio scholar John Gash suggests that the problem for the Carmelites may have been theological rather than aesthetic, in that Caravaggio's version fails to assert the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, the idea that the Mother of God did not die in any ordinary sense but was assumed into Heaven.[citation needed] The replacement altarpiece commissioned (from one of Caravaggio's most able followers, Carlo Saraceni), showed the Virgin not dead, as Caravaggio had painted her, but seated and dying; and even this was rejected, and replaced with a work showing the Virgin not dying, but ascending into Heaven with choirs of angels. In any case, the rejection did not mean that Caravaggio or his paintings were out of favour. The Death of the Virgin was no sooner taken out of the church than it was purchased by the Duke of Mantua, on the advice of Rubens, and later acquired by Charles I of England before entering the French royal collection in 1671.

One secular piece from these years is Amor Victorious, painted in 1602 for Vincenzo Giustiniani, a member of Del Monte's circle. The model was named in a memoir of the early 17th century as "Cecco", the diminutive for Francesco. He is possibly Francesco Boneri, identified with an artist active in the period 1610–1625 and known as Cecco del Caravaggio ('Caravaggio's Cecco'),[29] carrying a bow and arrows and trampling symbols of the warlike and peaceful arts and sciences underfoot. He is unclothed, and it is difficult to accept this grinning urchin as the Roman god Cupid – as difficult as it was to accept Caravaggio's other semi-clad adolescents as the various angels he painted in his canvases, wearing much the same stage-prop wings. The point, however, is the intense yet ambiguous reality of the work: it is simultaneously Cupid and Cecco, as Caravaggio's Virgins were simultaneously the Mother of Christ and the Roman courtesans who modeled for them.

A crime too many (1606)

St. Jerome, 1605–1606, Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Caravaggio led a tumultuous life. He was notorious for brawling, even in a time and place when such behavior was commonplace, and the transcripts of his police records and trial proceedings fill several pages. On 29 May 1606, he killed, possibly unintentionally, a young man named Ranuccio Tomassoni from Terni (Umbria). The circumstances of the brawl and the death of Ranuccio Tomassoni remain mysterious. Several contemporary avvisi referred to a quarrel over a gambling debt and a tennis game, and this explanation has become established in the popular imagination.[30] But recent scholarship has made it clear that more was involved. Good modern accounts are to be found in Peter Robb's M and Helen Langdon's Caravaggio: A Life. A theory relating the death to Renaissance notions of honour and symbolic wounding has been advanced by art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon.[31] Whatever the details, it was a serious matter.[32][33] Previously, his high-placed patrons had protected him from the consequences of his escapades, but this time they could do nothing. Caravaggio, outlawed, fled to Naples.

Exile and death (1606–1610)

Naples

The Seven Works of Mercy, 1606–1607, Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples

Following the death of Tomassoni, Caravaggio fled first to the estates of the Colonna family south of Rome, then on to Naples, where Costanza Colonna Sforza, widow of Francesco Sforza, in whose husband's household Caravaggio's father had held a position, maintained a palace. In Naples, outside the jurisdiction of the Roman authorities and protected by the Colonna family, the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples.

His connections with the Colonnas led to a stream of important church commissions, including the Madonna of the Rosary, and The Seven Works of Mercy.[34]The Seven Works of Mercy depicts the seven corporal works of mercy as a set of compassionate acts concerning the material needs of others. The painting was made for, and is still housed in, the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples. Caravaggio combined all seven works of mercy in one composition, which became the church's altarpiece.[35] Alessandro Giardino has also established the connection between the iconography of "The Seven Works of Mercy" and the cultural, scientific and philosophical circles of the painting's commissioners.[36]

Malta

Despite his success in Naples, after only a few months in the city Caravaggio left for Malta, the headquarters of the Knights of Malta. Fabrizio Sforza Colonna, Costanza's son, was a Knight of Malta and general of the Order's galleys. He appears to have facilitated Caravaggio's arrival in the island in 1607 (and his escape the next year). Caravaggio presumably hoped that the patronage of Alof de Wignacourt, Grand Master of the Knights of Saint John, could help him secure a pardon for Tomassoni's death.[37] De Wignacourt was so impressed at having the famous artist as official painter to the Order that he inducted him as a Knight, and the early biographer Bellori records that the artist was well pleased with his success.[37]

The Beheading of Saint John (1608) by Caravaggio (Saint John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta, Malta)

Major works from his Malta period include the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, his largest ever work, and the only painting to which he put his signature, Saint Jerome Writing (both housed in Saint John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta, Malta) and a Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page, as well as portraits of other leading Knights.[37] According to Andrea Pomella, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist is widely considered "one of the most important works in Western painting.".[38] Completed in 1608, the painting had been commissioned by the Knights of Malta as an altarpiece[38][39] and was the largest altarpiece Caravaggio painted.[40] It still hangs in St. John's Co-Cathedral, for which it was commissioned and where Caravaggio himself was inducted and briefly served as a knight.[41][40]

Yet, by late August 1608, he was arrested and imprisoned,[37] likely the result of yet another brawl, this time with an aristocratic knight, during which the door of a house was battered down and the knight seriously wounded.[37][42] Caravaggio was imprisoned by the Knights at Valletta, but he managed to escape. By December, he had been expelled from the Order "as a foul and rotten member", a formal phrase used in all such cases.[43]

Sicily

The Raising of Lazarus and the Adoration of the Shepherds, Regional Museum of Messina

Caravaggio made his way to Sicily where he met his old friend Mario Minniti, who was now married and living in Syracuse. Together they set off on what amounted to a triumphal tour from Syracuse to Messina and, maybe, on to the island capital, Palermo. In Syracuse and Messina Caravaggio continued to win prestigious and well-paid commissions. Among other works from this period are Burial of St. Lucy, The Raising of Lazarus, and Adoration of the Shepherds. His style continued to evolve, showing now friezes of figures isolated against vast empty backgrounds. "His great Sicilian altarpieces isolate their shadowy, pitifully poor figures in vast areas of darkness; they suggest the desperate fears and frailty of man, and at the same time convey, with a new yet desolate tenderness, the beauty of humility and of the meek, who shall inherit the earth."[44] Contemporary reports depict a man whose behaviour was becoming increasingly bizarre, which included sleeping fully armed and in his clothes, ripping up a painting at a slight word of criticism, and mocking local painters.

Caravaggio displayed bizarre behaviour from very early in his career. Mancini describes him as "extremely crazy", a letter of Del Monte notes his strangeness, and Minniti's 1724 biographer says that Mario left Caravaggio because of his behaviour. The strangeness seems to have increased after Malta. Susinno's early-18th-century Le vite de' pittori Messinesi ("Lives of the Painters of Messina") provides several colourful anecdotes of Caravaggio's erratic behaviour in Sicily, and these are reproduced in modern full-length biographies such as Langdon and Robb. Bellori writes of Caravaggio's "fear" driving him from city to city across the island and finally, "feeling that it was no longer safe to remain", back to Naples. Baglione says Caravaggio was being "chased by his enemy", but like Bellori does not say who this enemy was.

Return to Naples

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist

After only nine months in Sicily, Caravaggio returned to Naples in the late summer of 1609. According to his earliest biographer he was being pursued by enemies while in Sicily and felt it safest to place himself under the protection of the Colonnas until he could secure his pardon from the pope (now Paul V) and return to Rome.[45] In Naples he painted The Denial of Saint Peter, a final John the Baptist (Borghese), and his last picture, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. His style continued to evolve — Saint Ursula is caught in a moment of highest action and drama, as the arrow fired by the king of the Huns strikes her in the breast, unlike earlier paintings that had all the immobility of the posed models. The brushwork was also much freer and more impressionistic.

David with the Head of Goliath, 1609–1610, Galleria Borghese, Rome

In October 1609 he was involved in a violent clash, an attempt on his life, perhaps ambushed by men in the pay of the knight he had wounded in Malta or some other faction of the Order. His face was seriously disfigured and rumours circulated in Rome that he was dead. He painted a Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (Madrid), showing his own head on a platter, and sent it to de Wignacourt as a plea for forgiveness. Perhaps at this time, he painted also a David with the Head of Goliath, showing the young David with a strangely sorrowful expression gazing on the severed head of the giant, which is again Caravaggio. This painting he may have sent to his patron, the unscrupulous art-loving Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of the pope, who had the power to grant or withhold pardons.[46] Caravaggio hoped Borghese could mediate a pardon, in exchange for works by the artist.

News from Rome encouraged Caravaggio, and in the summer of 1610 he took a boat northwards to receive the pardon, which seemed imminent thanks to his powerful Roman friends. With him were three last paintings, the gifts for Cardinal Scipione.[47] What happened next is the subject of much confusion and conjecture, shrouded in much mystery.

The bare facts seem to be that on 28 July an anonymous avviso (private newsletter) from Rome to the ducal court of Urbino reported that Caravaggio was dead. Three days later another avviso said that he had died of fever on his way from Naples to Rome. A poet friend of the artist later gave 18 July as the date of death, and a recent researcher claims to have discovered a death notice showing that the artist died on that day of a fever in Porto Ercole, near Grosseto in Tuscany.[citation needed]

Death

Caravaggio had a fever at the time of his death, and what killed him has been a matter of historical debate and study.[48] Traditionally historians have long thought he died of syphilis.[48] Some have said he had malaria, or possibly brucellosis from unpasteurized dairy.[48] Some scholars have argued that Caravaggio was actually attacked and killed by the same "enemies" that had been pursuing him since he fled Malta, possibly Wignacourt and/or factions of the Knights.[49]

Human remains found in a church in Porto Ercole in 2010 are believed to almost certainly belong to Caravaggio.[50] The findings come after a year-long investigation using DNA, carbon dating and other analyses.[51] Initial tests suggested Caravaggio might have died of lead poisoning – paints used at the time contained high amounts of lead salts, and Caravaggio is known to have indulged in violent behavior, as caused by lead poisoning.[52] Later tests suggested he died as the result of a wound sustained in a brawl in Naples, specifically from sepsis.[48] Recently released Vatican documents (2002) also indicate that fatal wounds may have been sustained as a result of a vendetta, perpetrated after Caravaggio had murdered a love rival in a botched attempt at castration. [53]

Sexuality

Fillide Melandroni

Caravaggio never married and had no known children, and Howard Hibbard notes the absence of erotic female figures from the artist's oeuvre: "In his entire career he did not paint a single female nude."[54] On the other hand, the cabinet-pieces from the Del Monte period are replete with "full-lipped, languorous boys ... who seem to solicit the onlooker with their offers of fruit, wine, flowers – and themselves" suggesting an erotic interest in the male form.[55] At the same time, however, a connection with a certain Lena is mentioned in a 1605 court deposition by Pasqualone, where she is described as "Michelangelo's girl".[56] According to G.B. Passeri, this 'Lena' was Caravaggio's model for the Madonna di Loreto; and according to Catherine Puglisi, 'Lena' may have been the same person as the courtesan Maddalena di Paolo Antognetti, who named Caravaggio as an "intimate friend" by her own testimony in 1604.[57][58] Caravaggio also probably enjoyed close relationships with other "whores and courtesans" such as Fillide Melandroni, of whom he painted a portrait.[59]

Boy with a Basket of Fruit, 1593–1594, oil on canvas, 67 cm × 53 cm (26 in × 21 in), Galleria Borghese, Rome

Nevertheless, since the 1970s both art scholars and historians have debated the inferences of homoeroticism in Caravaggio's works as a way to better understand the man.[60] The model of "Amor vincit omnia", for example, is known to have been Cecco di Caravaggio. Cecco stayed with Caravaggio even after he was obliged to leave Rome in 1606, and the two may have been lovers.[61]

Caravaggio's sexuality also received early speculation due to claims about the artist by Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau. Writing in 1783, Mirabeau contrasted the personal life of Caravaggio directly with the writings of St Paul in the Book of Romans,[62] arguing that "Romans" excessively practice sodomy or homosexuality. The twenty-sixth verse of the first chapter[63] contains the Latin phrase: "Et fœminæ eorum immutaverunt naturalem usum in eum usum qui est contra naturam." The phrase, according to Mirabeau, entered Caravaggio's thoughts, and he claimed that such an "abomination" could be witnessed through a particular painting housed at the Museum of the Grand Duke of Tuscany – featuring a rosary of a blasphemous nature, in which a circle of thirty men (turpiter ligati) are intertwined in embrace and presented in unbridled composition. Mirabeau notes the affectionate nature of Caravaggio's depiction reflects the voluptuous glow of the artist's sexuality.[64] By the late nineteenth century, Sir Richard Francis Burton identified the painting as Caravaggio's painting of St. Rosario. Burton also identifies both St. Rosario and this painting with the practices of Tiberius mentioned by Seneca the Younger.[65] The survival status and location of Caravaggio's painting is unknown. No such painting appears in his or his school's catalogues.[66]

Sacred Love Versus Profane Love (1602–03), by Giovanni Baglione. Intended as an attack on his hated enemy, Caravaggio, it shows a boy (hinting at Caravaggio's alleged homosexuality) on one side, a devil with Caravaggio's face on the other, and between an angel representing pure, meaning non-erotic, love.

Aside from the paintings, evidence also comes from the libel trial brought against Caravaggio by Giovanni Baglione in 1603. Baglione accused Caravaggio and his friends of writing and distributing scurrilous doggerel attacking him; the pamphlets, according to Baglione's friend and witness Mao Salini, had been distributed by a certain Giovanni Battista, a bardassa, or boy prostitute, shared by Caravaggio and his friend Onorio Longhi. Caravaggio denied knowing any young boy of that name, and the allegation was not followed up.[67]

Baglione's painting of "Divine Love" has also been seen as a visual accusation of sodomy against Caravaggio.[59] Such accusations were damaging and dangerous as sodomy was a capital crime at the time. Even though the authorities were unlikely to investigate such a well-connected person as Caravaggio, "Once an artist had been smeared as a pederast, his work was smeared too."[61] Francesco Susino in his later biography additionally relates the story of how the artist was chased by a school-master in Sicily for spending too long gazing at the boys in his care. Susino presents it as a misunderstanding, but Caravaggio may indeed have been seeking sexual solace; and the incident could explain one of his most homoerotic paintings: his last depiction of St John the Baptist.[68]

The art historian, Andrew Graham-Dixon has summarised the debate:

A lot has been made of Caravaggio's presumed homosexuality, which has in more than one previous account of his life been presented as the single key that explains everything, both the power of his art and the misfortunes of his life. There is no absolute proof of it, only strong circumstantial evidence and much rumour. The balance of probability suggests that Caravaggio did indeed have sexual relations with men. But he certainly had female lovers. Throughout the years that he spent in Rome he kept close company with a number of prostitutes. The truth is that Caravaggio was as uneasy in his relationships as he was in most other aspects of life. He likely slept with men. He did sleep with women. He settled with no one... [but] the idea that he was an early martyr to the drives of an unconventional sexuality is an anachronistic fiction.[61]

As an artist

The birth of Baroque

The Taking of Christ, 1602, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Caravaggio's application of the chiaroscuro technique shows through on the faces and armour notwithstanding the lack of a visible shaft of light. The figure on the extreme right is a self-portrait.

Supper at Emmaus, 1601, oil on canvas, 139 cm × 195 cm (55 in × 77 in), National Gallery, London. Caravaggio included himself as the figure at the top left.

Caravaggio "put the oscuro (shadows) into chiaroscuro."[69] Chiaroscuro was practiced long before he came on the scene, but it was Caravaggio who made the technique a dominant stylistic element, darkening the shadows and transfixing the subject in a blinding shaft of light. With this came the acute observation of physical and psychological reality that formed the ground both for his immense popularity and for his frequent problems with his religious commissions.

He worked at great speed, from live models, scoring basic guides directly onto the canvas with the end of the brush handle; very few of Caravaggio's drawings appear to have survived, and it is likely that he preferred to work directly on the canvas. The approach was anathema to the skilled artists of his day, who decried his refusal to work from drawings and to idealise his figures. Yet the models were basic to his realism. Some have been identified, including Mario Minniti and Francesco Boneri, both fellow artists, Minniti appearing as various figures in the early secular works, the young Boneri as a succession of angels, Baptists and Davids in the later canvasses. His female models include Fillide Melandroni, Anna Bianchini, and Maddalena Antognetti (the "Lena" mentioned in court documents of the "artichoke" case[70] as Caravaggio's concubine), all well-known prostitutes, who appear as female religious figures including the Virgin and various saints.[71] Caravaggio himself appears in several paintings, his final self-portrait being as the witness on the far right to the Martyrdom of Saint Ursula.[72]

Caravaggio had a noteworthy ability to express in one scene of unsurpassed vividness the passing of a crucial moment. The Supper at Emmaus depicts the recognition of Christ by his disciples: a moment before he is a fellow traveler, mourning the passing of the Messiah, as he never ceases to be to the inn-keeper's eyes; the second after, he is the Saviour. In The Calling of St Matthew, the hand of the Saint points to himself as if he were saying "who, me?", while his eyes, fixed upon the figure of Christ, have already said, "Yes, I will follow you". With The Resurrection of Lazarus, he goes a step further, giving us a glimpse of the actual physical process of resurrection. The body of Lazarus is still in the throes of rigor mortis, but his hand, facing and recognizing that of Christ, is alive. Other major Baroque artists would travel the same path, for example Bernini, fascinated with themes from Ovid's Metamorphoses.[citation needed]

The Caravaggisti

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, 1601, Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

The installation of the St. Matthew paintings in the Contarelli Chapel had an immediate impact among the younger artists in Rome, and Caravaggism became the cutting edge for every ambitious young painter. The first Caravaggisti included Orazio Gentileschi and Giovanni Baglione. Baglione's Caravaggio phase was short-lived; Caravaggio later accused him of plagiarism and the two were involved in a long feud. Baglione went on to write the first biography of Caravaggio. In the next generation of Caravaggisti there were Carlo Saraceni, Bartolomeo Manfredi and Orazio Borgianni. Gentileschi, despite being considerably older, was the only one of these artists to live much beyond 1620, and ended up as court painter to Charles I of England. His daughter Artemisia Gentileschi was also close to Caravaggio, and one of the most gifted of the movement. Yet in Rome and in Italy it was not Caravaggio, but the influence of his rival Annibale Carracci, blending elements from the High Renaissance and Lombard realism, which ultimately triumphed.

Caravaggio's brief stay in Naples produced a notable school of Neapolitan Caravaggisti, including Battistello Caracciolo and Carlo Sellitto. The Caravaggisti movement there ended with a terrible outbreak of plague in 1656, but the Spanish connection – Naples was a possession of Spain – was instrumental in forming the important Spanish branch of his influence.

A group of Catholic artists from Utrecht, the "Utrecht Caravaggisti", travelled to Rome as students in the first years of the 17th century and were profoundly influenced by the work of Caravaggio, as Bellori describes. On their return to the north this trend had a short-lived but influential flowering in the 1620s among painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerrit van Honthorst, Andries Both and Dirck van Baburen. In the following generation the effects of Caravaggio, although attenuated, are to be seen in the work of Rubens (who purchased one of his paintings for the Gonzaga of Mantua and painted a copy of the Entombment of Christ), Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Velázquez, the last of whom presumably saw his work during his various sojourns in Italy.

Death and rebirth of a reputation

The Entombment of Christ, (1602–1603), Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome

Caravaggio's innovations inspired the Baroque, but the Baroque took the drama of his chiaroscuro without the psychological realism. While he directly influenced the style of the artists mentioned above, and, at a distance, the Frenchmen Georges de La Tour and Simon Vouet, and the Spaniard Giuseppe Ribera, within a few decades his works were being ascribed to less scandalous artists, or simply overlooked. The Baroque, to which he contributed so much, had evolved, and fashions had changed, but perhaps more pertinently Caravaggio never established a workshop as the Carracci did, and thus had no school to spread his techniques. Nor did he ever set out his underlying philosophical approach to art, the psychological realism that may only be deduced from his surviving work.

Thus his reputation was doubly vulnerable to the critical demolition-jobs done by two of his earliest biographers, Giovanni Baglione, a rival painter with a personal vendetta, and the influential 17th-century critic Gian Pietro Bellori, who had not known him but was under the influence of the earlier Giovanni Battista Agucchi and Bellori's friend Poussin, in preferring the "classical-idealistic" tradition of the Bolognese school led by the Carracci.[73] Baglione, his first biographer, played a considerable part in creating the legend of Caravaggio's unstable and violent character, as well as his inability to draw.[74]

In the 1920s, art critic Roberto Longhi brought Caravaggio's name once more to the foreground, and placed him in the European tradition: "Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt could never have existed without him. And the art of Delacroix, Courbet and Manet would have been utterly different".[75] The influential Bernard Berenson agreed: "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian painter exercised so great an influence."[76]

Epitaph

The Denial of Saint Peter (1610), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Caravaggio's epitaph was composed by his friend Marzio Milesi.[77] It reads:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Michelangelo Merisi, son of Fermo di Caravaggio – in painting not equal to a painter, but to Nature itself – died in Port' Ercole – betaking himself hither from Naples – returning to Rome – 15th calend of August – In the year of our Lord 1610 – He lived thirty-six years nine months and twenty days – Marzio Milesi, Jurisconsult – Dedicated this to a friend of extraordinary genius."[78]

He was commemorated on the front of the Banca d'Italia 100,000 lire banknote in the 1980s and 90s (before Italy switched to the Euro) with the back showing his Basket of Fruit.

Oeuvre

Conversion on the Way to Damascus, 1601, Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

There is disagreement as to the exact size of Caravaggio's oeuvre, with counts as low as 40 and as high as 80. In his biography, Caravaggio scholar Alfred Moir writes "The forty-eight colorplates in this book include almost all of the surviving works accepted by every Caravaggio expert as autograph, and even the least demanding would add fewer than a dozen more".[79] One, The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew, was recently authenticated and restored; it had been in storage in Hampton Court, mislabeled as a copy. Richard Francis Burton writes of a "picture of St. Rosario (in the museum of the Grand Duke of Tuscany), showing a circle of thirty men turpiter ligati" ("lewdly banded"), which is not known to have survived. The rejected version of The Inspiration of Saint Matthew, intended for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, was destroyed during the bombing of Dresden, though black and white photographs of the work exist. In June 2011 it was announced that a previously unknown Caravaggio painting of Saint Augustine dating to about 1600 had been discovered in a private collection in Britain. Called a "significant discovery", the painting had never been published and is thought to have been commissioned by Vincenzo Giustiniani, a patron of the painter in Rome.[80]

A painting believed by some experts to be Caravaggio's second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes, tentatively dated between 1600 and 1610, was discovered in an attic in Toulouse in 2014. An export ban was placed on the painting by the French government while tests were carried out to establish its provenance.[81][82] In February 2019 it was announced that the painting would be sold at auction after the Louvre had turned down the opportunity to purchase it for €100 million.[83]

Art theft

Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence, 1600

In October 1969, two thieves entered the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, Italy and stole Caravaggio's Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence from its frame.[84] Experts estimated its value at $20 million.[85][86]

Following the theft, Italian police set up an art theft task force with the specific aim of re-acquiring lost and stolen art works. Since the creation of this task force, many leads have been followed regarding the Nativity. Former Italian mafia members have stated that Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence was stolen by the Sicilian mafia and displayed at important mafia gatherings.[87] Former mafia members have said that the Nativity was damaged and has since been destroyed.[87]

The whereabouts of the artwork are still unknown. A reproduction currently hangs in its place in the Oratory of San Lorenzo.[87]

See also

Caravaggio portal

Caravaggio portal

Italian neorealism, a 1944–52 movement characterized by stories set amongst the disadvantaged- Utrecht Caravaggism

Footnotes

^ Carminati, Marco (25 February 2007). "Caravaggio da Milano" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Caravaggio - The Complete Works - caravaggio-foundation.org". www.caravaggio-foundation.org.

^ Vincenzio Fanti (1767). Descrizzione Completa di Tutto Ciò che Ritrovasi nella Galleria di Sua Altezza Giuseppe Wenceslao del S.R.I. Principe Regnante della Casa di Lichtenstein (in Italian). Trattner. p. 21.

^ "Italian Painter Michelangelo Amerighi da Caravaggio". Gettyimages.it. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

^ "Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da (Italian painter, 1571–1610)". Getty.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Quoted in Gilles Lambert, "Caravaggio", p.8.

^ "Confirmed by the finding of the baptism certificate from the Milanese parish of Santo Stefano in Brolo". Italica.rai.it. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ "Paris Art Studies Caravaggio". parisartstudies.com. 2009.

^ Malta Culture Guide. Retrieved 21 February 2017

^ Harris, p. 21.

^ Rosa Giorgi, "Caravaggio: Master of light and dark – his life in paintings", p.12.

^ Quoted without attribution in Robb, p.35, apparently based on the three primary sources, Mancini, Baglione and Bellori, all of whom depict Caravaggio's early Roman years as a period of extreme poverty (see references below).

^ Louise Brown, Beverly (2001). The Genius of Rome, 1592–1623. Royal Academy of Arts. p. 21. ISBN 9780900946882.

^ Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Le Vite de' pittori, scultori, et architetti moderni, 1672: "Michele was forced by necessity to enter the services of Cavalier Giuseppe d'Arpino, by whom he was employed to paint flowers and fruits so realistically that they began to attain the higher beauty that we love so much today."

^ Harris, Ann Sutherland, Seventeenth-century Art & Architecture (Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2008).

^ "Caravaggio". Hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Hibbard, Howard (1983). Caravaggio. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0500274910.

^ Catherine Puglisi, "Caravaggio", p. 79. Longhi was with Caravaggio on the night of the fatal brawl with Tomassoni; Robb, "M", p.341, believes that Minniti was as well.

^ H. Waga "Vita nota e ignota dei virtuosi al Pantheon" Rome 1992, Appendix I, pp. 219 and 220ff

^ "The earliest account of Caravaggio in Rome" Sandro Corradini and Maurizio Marini, The Burlington Magazine, pp. 25–28

^ Floris Claes van Dijk, a contemporary of Caravaggio in Rome in 1601, quoted in John Gash, "Caravaggio", p. 13. The quotation originates in Karel van Mander's Het Schilder-Boek of 1604, translated in full in Howard Hibbard, "Caravaggio".

^ Robb, p. 79. Robb is drawing on Bellori, who praises Caravaggio's "true" colours but finds the naturalism offensive: "He (Caravaggio) was satisfied with [the] invention of nature without further exercising his brain."

^ Bellori. The passage continues: "[The younger painters] outdid each other in copying him, undressing their models and raising their lights; and rather than setting out to learn from study and instruction, each readily found in the streets or squares of Rome both masters and models for copying nature."

^ For the details of the discovery, see the essay by eye-witness Noel Barber (superior of the Jesuit community in Dublin in which the painting had been found), in Saints and Sinners: Caravaggio and the Baroque Image, ed. Franco Mormando (Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 1999), catalog of the exhibition featuring the first display of the painting in the USA.

^ For an outline of the Counter-Reformation Church's policy on decorum in art, see Giorgi, p.80. For a more detailed discussion, see Gash, p.8ff; and for a discussion of the part played by notions of decorum in the rejection of "St Matthew and the Angel" and "Death of the Virgin", see Puglisi, pp.179–188.

^ Quoted without attribution in Lambert, p.66.

^ Mancini: "Thus one can understand how badly some modern artists paint, such as those who, wishing to portray the Virgin Our Lady, depict some dirty prostitute from the Ortaccio, as Michelangelo da Caravaggio did in the Death of the Virgin in that painting for the Madonna della Scala, which for that very reason those good fathers rejected it, and perhaps that poor man suffered so much trouble in his lifetime."

^ Baglione: "For the [church of] Madonna della Scala in Trastevere he painted the death of the Madonna, but because he had portrayed the Madonna with little decorum, swollen and with bare legs, it was taken away, and the Duke of Mantua bought it and placed it in his most noble gallery."

^ While Gianni Papi's identification of Cecco del Caravaggio as Francesco Boneri is widely accepted, the evidence connecting Boneri to Caravaggio's servant and model in the early 17th century is circumstantial. See Robb, pp193–196.

^ Baglione, Giovanni (1642). Life of Caravaggio. Italy. Archived from the original on 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2013-10-30. Because of the excessive ardour of his spirit Michelangelo was a little wild and he sometimes looked for the chance to break his neck or to risk the lives of others. People as quarrelsome as he were often to be found in his company: and having in the end confronted Ranuccio Tomassoni a well-mannered young man over some disagreement about a tennis match they challenged one another to a duel. After Ranuccio fell to the ground Michelangelo struck him with the point of his sword and having wounded him in the thigh killed him.

^ Milner, Catherine (2002-06-02). "'Red-blooded Caravaggio killed love rival in bungled castration attempt'". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

^ Willey, David (2011-02-18). "Caravaggio's crimes exposed in Rome's police files". bbc. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

^ Watkins, Ally (2011-02-24). "Caravaggio's Rap Sheet Reveals Him to Have Been a Lawless Sword-Obsessed Wildman, and a Terrible Renter". Artinfo. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Costanza's brother Ascanio was Cardinal-Protector of the Kingdom of Naples; another brother, Marzio, was an advisor to the Spanish Viceroy; and a sister was married into the important Neapolitan Carafa family. Caravaggio stayed in Costanza's palazzo on his return to Naples in 1609. These connections are treated in most biographies and studies—see, for example, Catherine Puglisi, "Caravaggio", p.258, for a brief outline. Helen Langdon, "Caravaggio: A Life", ch.12 and 15, and Peter Robb, "M", pp.398ff and 459ff, give a fuller account.

^ Ralf van Bühren, Caravaggio’s ‘Seven Works of Mercy’ in Naples, 2017.

^ Alessandro Giardino, The Seven Works of Mercy , 2017.

^ abcde Sammut, E. (1949). "Caravaggio in Malta" (PDF). Scientia. 15 (2): 78–89.

^ ab Pomella, Andrea (2005). Caravaggio: an artist through images. ATS Italia Editrice. p. 106. ISBN 978-88-88536-62-0. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

^ Varriano (2006), pp. 74, 116.

^ ab Patrick, James (2007). Renaissance and Reformation. Marshall Cavendish. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-7614-7651-1.

^ Rowland, Ingrid Drake (2005). From heaven to Arcadia: the sacred and the profane in the Renaissance. New York Review of Books. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-59017-123-3.

^ Sciberras, Keith (April 2002). "Frater Michael Angelus in tumultu: the cause of Caravaggio's imprisonment in Malta". The Burlington Magazine (CXLV): 229–232. and Sciberras, Keith (July 2002). "Riflessioni su Malta al tempo del Caravaggio". Paragone Arte. LII (629): 3–20. Sciberras' findings are summarised online at Caravaggio.com Archived 2006-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

^ The senior Knights of the Order convened on 1 December 1608 and, after verifying that the accused had failed to appear although summoned four times, voted unanimously to expel their putridum et foetidum ex-brother. Caravaggio was expelled, not for his crime, but for having left Malta without permission (i.e., escaping).

^ Langdon, p.365.

^ Baglione says that Caravaggio in Naples had "given up all hope of revenge" against his unnamed enemy.

^ According to a 17th-century writer the painting of the head of Goliath is a self-portrait of the artist, while David is il suo Caravaggino, "his little Caravaggio". This phrase is obscure, but it has been interpreted as meaning either that the boy is a youthful self-portrait, or, more commonly, that this is the Cecco who modeled for the Amor Vincit. The sword-blade carries an abbreviated inscription that has been interpreted as meaning Humility Conquers Pride. Attributed to a date in Caravaggio's late Roman period by Bellori, the recent tendency is to see it as a product on Caravaggio's second Neapolitan period. (See Gash, p.125).

^ A letter from the Bishop of Caserta in Naples to Cardinal Scipione Borghese in Rome, dated 29 July 1610, informs the Cardinal that the Marchesa of Caravaggio is holding two John the Baptists and a Magdalene that were intended for Borghese. These were presumably the price of Caravaggio's pardon from Borghese's uncle, the pope.

^ abcd Laura Geggel (September 28, 2018). "Renaissance Master Caravaggio Didn't Die of Syphilis, but of Sepsis". Live Science. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

^ Robb argues this in M beginning in chapter 20.

^ "BBC News – Vatican reveals Caravaggio painting 'found' in Rome". Bbc.co.uk. 2010-07-19. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ "BBC News – Church bones 'belong to Caravaggio', researchers say". Bbc.co.uk. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Tom Kington in Rome (2010-06-16). "The mystery of Caravaggio's death solved at last – painting killed him". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Correspondent, Catherine Milner, Arts (June 1, 2002). "'Red-blooded Caravaggio killed love rival in bungled castration attempt'" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

^ Hibbard, p.97

^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization (Harvard, 2006) p.288

^ Bertolotti, Artisti Lombardi. pp.71–72

^ Catheine Puglisi, "Caravaggio" Phaidon 1998, p.199

^ Riccardo Bassani and Fiora Bellini, "Caravaggio assassino", 1994, pp.205–214

^ ab Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A life sacred and profane, Penguin, 2011

^ https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/10/arts/design/10abroad.html?hp Herwarth Roettgen, Il Caravaggio, ricerche e interpretazione, Rome 1975; R. Longhi, ‘Novelletta del Caravaggio ‘’invertito’’, Paragone, March 1952, 62–4; Calvesi, ‘Caravaggio’, Art & Dossier, April 1986; Christopher Frommer, ‘Caravaggios frühwerk und der cardinal del Monte’, Storia dell’arte, 9–10 (1971): 5–29; Margaret Walters, The Male Nude, Harmondsworth, 1978: 188–189; Helen Langdon, Caravaggio; Robb, M

^ abc Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A life sacred and profane, Penguin, 2011, p.4

^ "Masculi, delicto naturali usu faeminae as exarserunt in desiriis suits in invicem, masculi in masculos, turpitudinem operant let mercidem quam oportuit erroris sui somatipsis recipient's."" – Romans I:27.

^ Romans I:26, cf. https://www.bibleserver.com/text/VUL/Romans1%3A26.

^ Mirabeau, Honoré (1867). Erotika Biblion. Chevalier de Pierrugues. Chez tous les Libraries.

^ Burton, Richard Francis (1900). A Plain and Literal Translation of "Arabian Nights." Volume 10. Press of The Carson-Harper Company.

^ White, Chris (1999). Nineteenth-Century Writings on Homosexuality: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 9780415153065.

^ The transcript of the trial is given in Walter Friedlander, "Caravaggio Studies" (Princeton, 1955, revised edn. 1969)

^ Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A life sacred and profane, Penguin, 2011, p.412

^ Lambert, p.11.

^ Much of the documentary evidence for Caravaggio's life in Rome comes from court records; the "artichoke" case refers to an occasion when the artist threw a dish of hot artichokes at a waiter.

^ Robb, passim, makes a fairly exhaustive attempt to identify models and relate them to individual canvases.

^ Caravaggio's self-portraits run from the Sick Bacchus at the beginning of his career to the head of Goliath in the David with the Head of Goliath in Rome's Borghese Gallery. Previous artists had included self-portraits as onlookers to the action, but Caravaggio's innovation was to include himself as a participant.

^ Wikkkower, p. 266; also see criticism by fellow Italian Vincenzo Carducci (living in Spain), who calls Caravaggio an "Antichrist" of painting with "monstrous" talents of deception.

^ Ostrow, 608

^ Roberto Longhi, quoted in Lambert, op. cit., p.15

^ Bernard Berenson, in Lambert, op. cit., p.8

^ Sohm, Philip (September 2002). "Caravaggio's Deaths". The Art Bulletin. 84 (3): 449–468. doi:10.1080/00043079.2002.10787031 (inactive 2019-02-09). JSTOR 3177308.

^ Inscriptiones et Elogia (Cod.Vat.7927)

^ Alfred Moir, "Caravaggio", p.9

^ Alberge, Dalya (19 June 2011). "Unknown Caravaggio painting unearthed in Britain". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

^ "Painting thought to be Caravaggio masterpiece found in French loft". BBC News Online. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

^ 'Lost Caravaggio,' found in a French attic, causes rift in the art world, The Guardian, Angelique Chrisafis, April 12, 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

^ Brown, Mark (28 February 2019). "'Lost Caravaggio' rejected by the Louvre may be worth £100m". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

^ Kirchgaessner, Stephanie (10 December 2015). "'Restitution of a lost beauty': Caravaggio Nativity replica brought to Palermo". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

^ "FBI — Caravaggio". Fbi.gov. 2012-09-17. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ Sooke, Alastair (23 December 2013). "Caravaggio's Nativity: Hunting a stolen masterpiece". BBC website. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

^ abc "The World's Most Expensive Stolen Paintings – BBC Two". BBC. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

References

Primary sources

The main primary sources for Caravaggio's life are:

- Giulio Mancini's comments on Caravaggio in Considerazioni sulla pittura, c.1617–1621

- Giovanni Baglione's Le vite de' pittori, 1642

- Giovanni Pietro Bellori's Le Vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, 1672

All have been reprinted in Howard Hibbard's Caravaggio and in the appendices to Catherine Puglisi's Caravaggio.

Secondary sources

Andrea Bayer (2004). Painters of reality : the legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588391162.

- Erin Benay (2017) Exporting Caravaggio: the Crucifixion of St. Andrew Giles Press Ltd.

ISBN 978-1911282242

Ralf van Bühren, Caravaggio’s ‘Seven Works of Mercy’ in Naples. The relevance of art history to cultural journalism, in Church, Communication and Culture 2 (2017), pp. 63–87- Maurizio Calvesi, Caravaggio, Art Dossier 1986, Giunti Editori (1986) (ISBN not available)

Maurizio Calvesi (1990). Le realtà del Caravaggio (in Italian). Torino: G. Einaudi.

John Denison Champlin and Charles Callahan Perkins, Ed., Cyclopedia of Painters and Paintings, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York (1885), p. 241 (available at the Harvard's Fogg Museum Library and scanned on Google Books)

Keith Christiansen. (1990). A Caravaggio Rediscovered, The Lute Player. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870995750.

- Andrea Dusio, Caravaggio White Album, Cooper Arte, Roma 2009,

ISBN 978-88-7394-128-6

- Michael Fried, The Moment of Caravaggio, Yale University Press, 2010, ISB: 9780691147017, Review

- Walter Friedlaender, Caravaggio Studies, Princeton: Princeton University Press 1955

- John Gash, Caravaggio, Chaucer Press, (2004)

ISBN 1-904449-22-0) - Rosa Giorgi, Caravaggio: Master of light and dark – his life in paintings, Dorling Kindersley (1999)

ISBN 978-0-7894-4138-6

Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, London, Allen Lane, 2009.

ISBN 978-0-7139-9674-6

- Jonathan Harr (2005). The Lost Painting: The Quest for a Caravaggio Masterpiece. New York: Random House. ["The Taking of Christ"]

- Howard Hibbard, Caravaggio (1983)

ISBN 978-0-06-433322-1

- Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-century Art & Architecture, Laurence King Publishing (2004),

ISBN 1-85669-415-1.

Michael Kitson, The Complete Paintings of Caravaggio London, Abrams, 1967. New edition: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969 and 1986,

ISBN 978-0-297-76108-2

- Pietro Koch, Caravaggio – The Painter of Blood and Darkness, Gunther Edition, (Rome – 2004)

- Gilles Lambert, Caravaggio, Taschen, (2000)

ISBN 978-3-8228-6305-3

- Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999 (original UK edition 1998)

ISBN 978-0-374-11894-5

Denis Mahon (1947). Studies in Seicento Art. London: Warburg Institute.

Alfred Moir, The Italian Followers of Caravaggio, Harvard University Press (1967)

ISBN 978-0674469006

- Ostrow, Steven F., review of Giovanni Baglione: Artistic Reputation in Baroque Rome by Maryvelma Smith O'Neil, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 85, No. 3 (Sep., 2003), pp. 608–611, online text

- Catherine Puglisi, Caravaggio, Phaidon (1998)

ISBN 978-0-7148-3966-0

Peter Robb, M, Duffy & Snellgrove, 2003 amended edition (original edition 1998)

ISBN 978-1-876631-79-6

- Rudolph, Conrad and Steven Ostrow, "Isaac Laughing: Caravaggio, Non-traditional Imagery, and Traditional Identification," Art History 24 (2001) 646–681

John Spike, with assistance from Michèle Kahn Spike, Caravaggio with Catalogue of Paintings on CD-ROM, Abbeville Press, New York (2001)

ISBN 978-0-7892-0639-8

- John L. Varriano, Caravaggio: The Art of Realism, Pennsylvania State University Press (University Park, PA – 2006)

ISBN 978-0271027180

Rudolf Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750, Penguin/Yale History of Art, 3rd edition, 1973,

ISBN 978-0300079395

Alberto Macchi, "L'uomo Caravaggio" – Atto unico (pref. Stefania Macioce), AETAS, Roma 1995,

ISBN 88-851-72-19-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. |

Biography

- Caravaggio, The Prince of the Night

Articles and essays

- Christiansen, Keith. “Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (1571–1610) and his Followers.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2003)

- FBI Art Theft Notice for Caravaggio's Nativity

- The Passion of Caravaggio

- Deconstructing Caravaggio and Velázquez

- Interview with Peter Robb, author of M

Compare Rembrandt with Caravaggio.- Caravaggio and the Camera Obscura

- Caravaggio's incisions by Ramon van de Werken

- Caravaggio's use of the Camera Obscura: Lapucci

- Some notes on Caravaggio – Patrick Swift

- Roberta Lapucci's website and most of her publications on Caravaggio as freely downloadable PDF

Art works

caravaggio-foundation.org 175 works by Caravaggio

caravaggio.org Analysis of 100 important Caravaggio works- Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio WebMuseum, Paris webpage

- Caravaggio's EyeGate Gallery

Music

- Lachrimae Caravaggio, by Jordi Savall, performed by Le Concert des Nations & Hesperion XXI (Article at Answers.com)

Video

Caravaggio's Calling of Saint Matthew at Smarthistory, accessed February 13, 2013

Caravaggio's Crucifixion of Saint Peter, accessed February 13, 2013

Caravaggio's Death of the Virgin, accessed February 13, 2013

Caravaggio's Narcissus at the Source, accessed February 13, 2013

Caravaggio's paintings in the Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, accessed February 13, 2013

Caravaggio's Supper at Emmaus, accessed February 13, 2013