Vasopressin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌveɪzoʊˈprɛsɪn/ |

| Synonyms | Arginine Vasopressin; Argipressin |

| ATC code |

|

Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | Supraoptic nucleus; Paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus |

| Target tissues | System-wide |

| Receptors | V1A, V1B, V2, OXTR |

| Agonists | Felypressin, Desmopressin |

| Antagonists | Diuretics |

| Metabolism | Predominantly in the liver and kidneys |

Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 1% |

| Metabolism | Predominantly in the liver and kidneys |

| Elimination half-life | 10-20 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C46H65N15O12S2 |

| Molar mass | 1,084.24 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| Density | 1.6±0.1 g/cm3 |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| AVP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | AVP, ADH, ARVP, AVP-NPII, AVRP, VP, arginine vasopressin, Vasopressin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

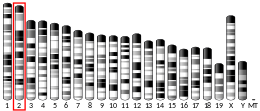

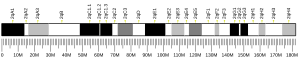

| External IDs | OMIM: 192340 MGI: 88121 HomoloGene: 417 GeneCards: AVP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Entrez |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| UniProt |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 20: 3.08 – 3.08 Mb | Chr 2: 130.58 – 130.58 Mb | |||||||||||||||||||||||

PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vasopressin, also called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), arginine vasopressin (AVP) or argipressin,[5] is a hormone synthesized as a peptide prohormone in neurons in the hypothalamus, and is converted to AVP. It then travels down the axon of that cell, which terminates in the posterior pituitary, and is released from vesicles into the circulation in response to extracellular fluid hypertonicity (hyperosmolality). AVP has two primary functions. First, it increases the amount of solute-free water reabsorbed back into the circulation from the filtrate in the kidney tubules of the nephrons. Second, AVP constricts arterioles, which increases peripheral vascular resistance and raises arterial blood pressure.[6][7][8]

A third function is possible. Some AVP may be released directly into the brain from the hypothalamus, and may play an important role in social behavior, sexual motivation and pair bonding, and maternal responses to stress.[9]

Vasopressin induces differential of stem cells into cardiomyocytes and promotes heart muscle homeostasis.[10]

It has a very short half-life, between 16–24 minutes.[8]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 Physiology

1.1 Function

1.1.1 Kidney

1.1.2 Central nervous system

1.2 Regulation

1.3 Production and secretion

1.4 Receptors

1.5 Structure and relation to oxytocin

2 Medical use

2.1 Pharmacokinetics

2.2 Side effects

2.3 Contraindications

2.4 Interactions

3 Role in disease

3.1 Deficiency

3.2 Excess

4 History

5 Animal studies

6 Human studies

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

Physiology

Function

Vasopressin regulates the tonicity of body fluids. It is released from the posterior pituitary in response to hypertonicity and causes the kidneys to reabsorb solute-free water and return it to the circulation from the tubules of the nephron, thus returning the tonicity of the body fluids toward normal. An incidental consequence of this renal reabsorption of water is concentrated urine and reduced urine volume. AVP released in high concentrations may also raise blood pressure by inducing moderate vasoconstriction.

AVP also may have a variety of neurological effects on the brain. It may influence pair-bonding in voles. The high-density distributions of vasopressin receptor AVPr1a in prairie vole ventral forebrain regions have been shown to facilitate and coordinate reward circuits during partner preference formation, critical for pair bond formation.[11]

A very similar substance, lysine vasopressin (LVP) or lypressin, has the same function in pigs and is used in human AVP deficiency.[12]

Kidney

Vasopressin has three main effects:

- Increasing the water permeability of initial and cortical collecting tubules (ICT & CCT), as well as outer and inner medullary collecting duct (OMCD & IMCD) in the kidney, thus allowing water reabsorption and excretion of more concentrated urine, i.e., antidiuresis. This occurs through increased transcription and insertion of water channels (Aquaporin-2) into the apical membrane of collecting tubule and collecting duct epithelial cells. [13] Aquaporins allow water to move down their osmotic gradient and out of the nephron, increasing the amount of water re-absorbed from the filtrate (forming urine) back into the bloodstream. This effect is mediated by V2 receptors. Vasopressin also increases the concentration of calcium in the collecting duct cells, by episodic release from intracellular stores. Vasopressin, acting through cAMP, also increases transcription of the aquaporin-2 gene, thus increasing the total number of aquaporin-2 molecules in collecting duct cells.[citation needed]

- Increasing permeability of the inner medullary portion of the collecting duct to urea by regulating the cell surface expression of urea transporters,[14] which facilitates its reabsorption into the medullary interstitium as it travels down the concentration gradient created by removing water from the connecting tubule, cortical collecting duct, and outer medullary collecting duct.

- Acute increase of sodium absorption across the ascending loop of henle. This adds to the countercurrent multiplication which aids in proper water reabsorption later in the distal tubule and collecting duct.[15]

Central nervous system

Vasopressin released within the brain may have several actions:

- Vasopressin is released into the brain in a circadian rhythm by neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus.[16]

- Vasopressin released from centrally projecting hypothalamic neurons is involved in aggression, blood pressure regulation, and temperature regulation.[citation needed]-->

- Recent evidence suggests that vasopressin may have analgesic effects. The analgesia effects of vasopressin were found to be dependent on both stress and sex.[17]

Regulation

Many factors influence the secretion of vasopressin:

Ethanol (alcohol) reduces the calcium-dependent secretion of AVP by blocking voltage-gated calcium channels in neurohypophyseal nerve terminals in rats.[18]

Angiotensin II stimulates AVP secretion, in keeping with its general pressor and pro-volumic effects on the body.[19]

Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits AVP secretion, in part by inhibiting Angiotensin II-induced stimulation of AVP secretion.[19]

Cortisol inhibits secretion of antidiuretic hormone.[20]

Production and secretion

The physiologic stimulus for secretion of vasopressin is increased osmolality of the plasma, monitored by the hypothalamus. A decreased arterial blood volume, (such as can occur in cirrhosis, nephrosis and heart failure), stimulates secretion, even in the face of decreased osmolality of the plasma: it supersedes osmolality, but

with a milder effect. In other words, vasopressin is secreted in spite of the presence of hypoosmolality (hyponatremia) when the arterial blood volume is low.

The AVP that is measured in peripheral blood is almost all derived from secretion from the posterior pituitary gland (except in cases of AVP-secreting tumours). Vasopressin is produced by magnocellular neurosecretory neurons in the Paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN) and Supraoptic nucleus (SON). It then travels down the axon through the infundibulum within neurosecretory granules that are found within Herring bodies, localized swellings of the axons and nerve terminals. These carry the peptide directly to the posterior pituitary gland, where it is stored until released into the blood.

There are other sources of AVP, beyond the hypothalamic magnocellular neurons. For example, AVP is also synthesized by parvocellular neurosecretory neurons of the PVN, transported and released at the median eminence, from which it travels through the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary, where it stimulates corticotropic cells synergistically with CRH to produce ACTH (by itself it is a weak secretagogue).[21]

Receptors

The following describes the actions of AVP:

| Type | Second messenger system | Locations | Actions | Agonists | Antagonists |

| AVPR1A | Phosphatidylinositol/calcium | Liver, kidney, peripheral vasculature, brain | Vasoconstriction, gluconeogenesis, platelet aggregation, and release of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor; social recognition,[22] circadian tau[23] | Felypressin | |

| AVPR1B or AVPR3 | Phosphatidylinositol/calcium | Pituitary gland, brain | Adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion in response to stress;[24] social interpretation of olfactory cues[25] | ||

| AVPR2 | Adenylate cyclase/cAMP | Basolateral membrane of the cells lining the collecting ducts of the kidneys (especially the cortical and outer medullary collecting ducts) | Insertion of aquaporin-2 (AQP2) channels (water channels). This allows water to be reabsorbed down an osmotic gradient, and so the urine is more concentrated. Release of von Willebrand factor and surface expression of P-selectin through exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies from endothelial cells[26][27] | AVP, desmopressin | "-vaptan" diuretics, i.e. tolvaptan |

Structure and relation to oxytocin

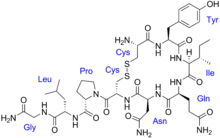

Chemical structure of the arginine vasopressin (argipressin) with an arginine at the 8th amino acid position. Lysine vasopressin differs only in having a lysine in this position.

Chemical structure of oxytocin

The vasopressins are peptides consisting of nine amino acids (nonapeptides). (NB: the value in the table above of 164 amino acids is that obtained before the hormone is activated by cleavage.) The amino acid sequence of arginine vasopressin (argipressin) is Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2, with the cysteine residues forming a disulfide bond and the C-terminus of the sequence converted to a primary amide.[28] Lysine vasopressin (lypressin) has a lysine in place of the arginine as the eighth amino acid, and is found in pigs and some related animals, whereas arginine vasopressin is found in humans.[29]

The structure of oxytocin is very similar to that of the vasopressins: It is also a nonapeptide with a disulfide bridge and its amino acid sequence differs at only two positions (see table below). The two genes are located on the same chromosome separated by a relatively small distance of less than 15,000 bases in most species. The magnocellular neurons that secrete vasopressin are adjacent to magnocellular neurons that secrete oxytocin, and are similar in many respects. The similarity of the two peptides can cause some cross-reactions: oxytocin has a slight antidiuretic function, and high levels of AVP can cause uterine contractions.[30][31]

Below is a table showing the superfamily of vasopressin and oxytocin neuropeptides:

Vertebrate Vasopressin Family | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Argipressin (AVP, ADH) | Most mammals |

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Lys-Gly-NH2 | Lypressin (LVP) | Pigs, hippos, warthogs, some marsupials |

| Cys-Phe-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Phenypressin | Some marsupials |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Vasotocin† | Non-mammals |

Vertebrate Oxytocin Family | ||

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 | Oxytocin (OXT) | Most mammals, ratfish |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Pro-Gly-NH2 | Prol-Oxytocin | Some New World monkeys, northern tree shrews |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Mesotocin | Most marsupials, all birds, reptiles, amphibians, lungfishes, coelacanths |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Ser-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Seritocin | Frogs |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Ser-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Isotocin | Bony fishes |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Ser-Asn-Cys-Pro-Gln-Gly-NH2 | Glumitocin | skates |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Asn/Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Leu/Val-Gly-NH2 | Various tocins | Sharks |

Invertebrate VP/OT Superfamily | ||

| Cys-Leu-Ile-Thr-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Inotocin | Locust |

| Cys-Phe-Val-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Thr-Gly-NH2 | Annetocin | Earthworm |

| Cys-Phe-Ile-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Lys-Gly-NH2 | Lys-Connopressin | Geography & imperial cone snail, pond snail, sea hare, leech |

| Cys-Ile-Ile-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Arg-Connopressin | Striped cone snail |

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Cephalotocin | Octopus |

| Cys-Phe-Trp-Thr-Ser-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Octopressin | Octopus |

| †Vasotocin is the evolutionary progenitor of all the vertebrate neurohypophysial hormones.[32] | ||

Medical use

Vasopressin is used to manage anti-diuretic hormone deficiency. It has off-label uses and is used in the treatment of vasodilatory shock, gastrointestinal bleeding, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. Vasopressin is used to treat diabetes insipidus related to low levels of antiduretic hormone. It is available as Pressyn.[33]

Vasopressin agonists are used therapeutically in various conditions, and its long-acting synthetic analogue desmopressin is used in conditions featuring low vasopressin secretion, as well as for control of bleeding (in some forms of von Willebrand disease and in mild haemophilia A) and in extreme cases of bedwetting by children. Terlipressin and related analogues are used as vasoconstrictors in certain conditions. Use of vasopressin analogues for esophageal varices commenced in 1970.[34]

Vasopressin infusions are also used as second line therapy for septic shock patients not responding to fluid resuscitation or infusions of catecholamines (e.g., dopamine or norepinephrine) to increase the blood pressure while sparing the use of catecholamines. These argipressins have much shorter elimination half-life (around 20 minutes) comparing to synthetic non-arginine vasopresines with much longer elimination half-life of many hours. Further, argipressins act on V1a, V1b, and V2 reseptors which consequently lead to higher eGFR and lower vascular resistance in the lungs. A number of injectable arginine vasopressins are currently in clinical use in the United States and in Europe.

Pharmacokinetics

Vasopressin is administered through an intravenous device, intramuscular injection or a subcutaneous injection. The duration of action depends on the mode of administration and ranges from thirty minutes to two hours. It has a half life of ten to twenty minutes. It is widely distributed throughout the body and remains in the extracellular fluid. It is degraded by the liver and excreted through the kidneys.[33]. Arginin vasopressins for use in septic shock are intended for intravenouse use only.

Side effects

The most common side effects during treatment with vasopressin are dizziness, angina, chest pain, abdominal cramps, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, trembling, fever, water intoxication, pounding sensation in the head, diarrhea, sweating, paleness, and flatulence. The most severe adverse reactions are myocardial infarction and hypersensitivy.[33]

Contraindications

The use of lysine vasopressin is contraindicated in the presence of hypersentivity to beef or pork proteins, increased BUN and chronic renal failure. It recommended that it be cautiously used in instances of perioperative polyuria, sensitivity to the drug, asthma, seizures, heart failure, a comatose state, migraine headaches, and cardiovascular disease.[33]

Interactions

alcohol - may lower the antidiuretic effect

carbamazepine, chloropropamide, clofibrate, tricyclic antidepressants fludrocortisone may raise the diuretic effect

lithium, demeclocycline, heparin or norepinephrine may lower the antidiuretic effect- vasopressor effect may be higher with the concurrent use of ganglionic blocking medications[33]

Role in disease

There may be a connection between arginine vasopressin and autism.[35]

Deficiency

Decreased AVP release (neurogenic — i.e. due to alcohol intoxication or tumour) or decreased renal sensitivity to AVP (nephrogenic, i.e. by mutation of V2 receptor or AQP) leads to diabetes insipidus, a condition featuring hypernatremia (increased blood sodium concentration), polyuria (excess urine production), and polydipsia (thirst).

Excess

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone secretion (SIADH) in turn can be caused by a number of problems. Some forms of cancer can cause SIADH, particularly small cell lung carcinoma but also a number of other tumors. A variety of diseases affecting the brain or the lung (infections, bleeding) can be the driver behind SIADH. A number of drugs has been associated with SIADH, such as certain antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants), the anticonvulsant carbamazepine, oxytocin (used to induce and stimulate labor), and the chemotherapy drug vincristine. It has also been associated with fluoroquinolones (including ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin).[8] Finally, it can occur without a clear explanation.[36] Hyponatremia can be treated pharmaceutically through the use of vasopressin receptor antagonists.[36]

History

Vasopressin was elucidated and synthesized for the first time by Vincent du Vigneaud.

Animal studies

Evidence for an effect of AVP on monogamy vs promiscuity comes from experimental studies in several species, which indicate that the precise distribution of vasopressin and vasopressin receptors in the brain is associated with species-typical patterns of social behavior. In particular, there are consistent differences between monogamous species and promiscuous species in the distribution of AVP receptors, and sometimes in the distribution of vasopressin-containing axons, even when closely related species are compared.[37]

Human studies

Vasopressin has shown nootropic effects on pain perception and cognitive function.[38] Vasopressin also plays a role in autism, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.[39]

See also

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone secretion (SIADH)

- Oxytocin

- Sexual motivation and hormones

- Vasopressin receptor

- Vasopressin receptor antagonists

- Copeptin

References

^ abc GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000101200 - Ensembl, May 2017

^ abc GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000037727 - Ensembl, May 2017

^ "Human PubMed Reference:"..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

^ Anderson DA (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

^ Marieb E (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-321-86158-0.

^ Caldwell HK, Young WS III (2006). "Oxytocin and Vasopressin: Genetics and Behavioral Implications" (PDF). In Lajtha A, Lim R. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology: Neuroactive Proteins and Peptides (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. pp. 573–607. ISBN 0-387-30348-0.

^ abc Babar SM (October 2013). "SIADH associated with ciprofloxacin". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (10): 1359–63. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. PMID 24259701.

^ Insel TR (March 2010). "The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior". Neuron. 65 (6): 768–79. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005. PMC 2847497. PMID 20346754.

^ Costa A, Rossi E, Scicchitano BM, Coletti D, Moresi V, Adamo S (September 2014). "Neurohypophyseal Hormones: Novel Actors of Striated Muscle Development and Homeostasis". review. European Journal of Translational Myology. 24 (3): 3790. doi:10.4081/ejtm.2014.3790. PMC 4756744. PMID 26913138.

^ Lim MM, Young LJ (2004). "Vasopressin-dependent neural circuits underlying pair bond formation in the monogamous prairie vole". Neuroscience. 125 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.008. PMID 15051143.

^ Chapman IM, Professor of Medicine, Discipline of Medicine, University of Adelaide, Royal Adelaide Hospital. "Central Diabetes Insipidus". MSD. Merck & Co. Inc.

^ Boron WR, Boulpaep EL. Medical Physiology (Third ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 978-1-4557-4377-3. OCLC 951680737.

^ Sands JM, Blount MA, Klein JD (2011). "Regulation of renal urea transport by vasopressin". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 122: 82–92. PMC 3116377. PMID 21686211.

^ Knepper MA, Kim GH, Fernández-Llama P, Ecelbarger CA (March 1999). "Regulation of thick ascending limb transport by vasopressin". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10 (3): 628–34. PMID 10073614.

^ Forsling ML, Montgomery H, Halpin D, Windle RJ, Treacher DF (May 1998). "Daily patterns of secretion of neurohypophysial hormones in man: effect of age". Experimental Physiology. 83 (3): 409–18. PMID 9639350.

^ Wiltshire T, Maixner W, Diatchenko L (December 2011). "Relax, you won't feel the pain". Nature Neuroscience. 14 (12): 1496–7. doi:10.1038/nn.2987. PMID 22119947.

^ Wang XM, Dayanithi G, Lemos JR, Nordmann JJ, Treistman SN (November 1991). "Calcium currents and peptide release from neurohypophysial terminals are inhibited by ethanol". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 259 (2): 705–11. PMID 1941619.

^ ab Matsukawa T, Miyamoto T (March 2011). "Angiotensin II-stimulated secretion of arginine vasopressin is inhibited by atrial natriuretic peptide in humans". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 300 (3): R624–9. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00324.2010. PMID 21123762.

^ Collège des enseignants d'endocrinologie, diabète et maladie (2012-01-30). Endocrinologie, diabétologie et maladies métaboliques. Elsevier Masson. ISBN 978-2-294-72233-2.

^ Salata RA, Jarrett DB, Verbalis JG, Robinson AG (March 1988). "Vasopressin stimulation of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) in humans. In vivo bioassay of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) which provides evidence for CRF mediation of the diurnal rhythm of ACTH". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 81 (3): 766–74. doi:10.1172/JCI113382. PMC 442524. PMID 2830315.

^ Bielsky IF, Hu SB, Szegda KL, Westphal H, Young LJ (March 2004). "Profound impairment in social recognition and reduction in anxiety-like behavior in vasopressin V1a receptor knockout mice". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (3): 483–93. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300360. PMID 14647484.

^ Wersinger SR, Caldwell HK, Martinez L, Gold P, Hu SB, Young WS (August 2007). "Vasopressin 1a receptor knockout mice have a subtle olfactory deficit but normal aggression". Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 6 (6): 540–51. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00281.x. PMID 17083331.

^ Lolait SJ, Stewart LQ, Jessop DS, Young WS, O'Carroll AM (February 2007). "The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress in mice lacking functional vasopressin V1b receptors". Endocrinology. 148 (2): 849–56. doi:10.1210/en.2006-1309. PMC 2040022. PMID 17122081.

^ Wersinger SR, Kelliher KR, Zufall F, Lolait SJ, O'Carroll AM, Young WS (December 2004). "Social motivation is reduced in vasopressin 1b receptor null mice despite normal performance in an olfactory discrimination task". Hormones and Behavior. 46 (5): 638–45. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.07.004. PMID 15555506.

^ Kanwar S, Woodman RC, Poon MC, Murohara T, Lefer AM, Davenpeck KL, Kubes P (October 1995). "Desmopressin induces endothelial P-selectin expression and leukocyte rolling in postcapillary venules". Blood. 86 (7): 2760–6. PMID 7545469.

^ Kaufmann JE, Oksche A, Wollheim CB, Günther G, Rosenthal W, Vischer UM (July 2000). "Vasopressin-induced von Willebrand factor secretion from endothelial cells involves V2 receptors and cAMP". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 106 (1): 107–16. doi:10.1172/JCI9516. PMC 314363. PMID 10880054.

^ Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1833. ISBN 978-1-4557-5942-2.

^ Donaldson D (1994). "Polyuria and Disorders of Thirst". In Williams DL, Marks V. Scientific Foundations of Biochemistry in Clinical Practice (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 76–102. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7506-0167-2.50010-8. ISBN 978-0-7506-0167-2.

^ Li C, Wang W, Summer SN, Westfall TD, Brooks DP, Falk S, Schrier RW (February 2008). "Molecular mechanisms of antidiuretic effect of oxytocin". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 19 (2): 225–32. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007010029. PMC 2396735. PMID 18057218.

^ Joo KW, Jeon US, Kim GH, Park J, Oh YK, Kim YS, Ahn C, Kim S, Kim SY, Lee JS, Han JS (October 2004). "Antidiuretic action of oxytocin is associated with increased urinary excretion of aquaporin-2". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 19 (10): 2480–6. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh413. PMID 15280526.

^ Acher R, Chauvet J (July 1995). "The neurohypophysial endocrine regulatory cascade: precursors, mediators, receptors, and effectors". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 16 (3): 237–89. doi:10.1006/frne.1995.1009. PMID 7556852.

^ abcde "Vasopressin" (PDF). F.A. Davis Company. 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

^ Baum S, Nusbaum M (March 1971). "The control of gastrointestinal hemorrhage by selective mesenteric arterial infusion of vasopressin". Radiology. 98 (3): 497–505. doi:10.1148/98.3.497. PMID 5101576.

^ Carson DS, Garner JP, Hyde SA, Libove RA, Berquist SW, Hornbeak KB, Jackson LP, Sumiyoshi RD, Howerton CL, Hannah SL, Partap S, Phillips JM, Hardan AY, Parker KJ (2015). "Arginine Vasopressin Is a Blood-Based Biomarker of Social Functioning in Children with Autism". PLoS One. 10 (7): e0132224. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132224. PMC 4511760. PMID 26200852. Lay summary – Scientific American.

^ ab Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH (November 2007). "Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (11 Suppl 1): S1–21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001. PMID 17981159.

^ Young LJ (October 2009). "The neuroendocrinology of the social brain". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 30 (4): 425–8. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.06.002. PMID 19596026.

^ Mavani GP, DeVita MV, Michelis MF (2015). "A review of the nonpressor and nonantidiuretic actions of the hormone vasopressin". Frontiers in Medicine. 2: 19. doi:10.3389/fmed.2015.00019. PMC 4371647. PMID 25853137.

^ Iovino M, Messana T, De Pergola G, Iovino E, Dicuonzo F, Guastamacchia E, Giagulli VA, Triggiani V (2018). "The Role of Neurohypophyseal Hormones Vasopressin and Oxytocin in Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 18 (4): 341–347. doi:10.2174/1871530318666180220104900. PMID 29468985.

Further reading

Rector FC, Brenner BM (2004). Brenner & Rector's the kidney (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0164-9.

Mastropietro CW (May 2013). "Arginine vasopressin and paediatric cardiovascular surgery". OA Critical Care. 1 (1): 7. doi:10.13172/2052-9309-1-1-680.