Vojvodina

Coordinates: 45°24′58″N 20°11′53″E / 45.416°N 20.198°E / 45.416; 20.198

Autonomous Province of Vojvodina

| |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Traditional Symbols of Vojvodina   | |

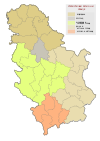

Map of Vojvodina within Serbia | |

| Capital and largest city | Novi Sad (Administrative centre) |

| Official languages |

|

| Country | |

| Government | Autonomous province |

• President of the Government | Igor Mirović (SNS) |

• President of the Assembly | István Pásztor (SVM) |

| Legislature | Assembly |

| Establishment | |

• Formation of Serbian Vojvodina | 1848 |

• Establishment | 1944 |

| Area | |

• Total | 21,506 km2 (8,304 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2011 census | 1,931,809 |

• Density | 90/km2 (233.1/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Vojvodina (Serbian and Croatian: Vojvodina [ʋǒjʋodina] (![]() listen); Serbian Cyrillic: Војводина; Pannonian Rusyn: Войводина; Hungarian: Vajdaság [ˈvɒjdɒʃaːɡ]; Slovak and Czech: Vojvodina; Romanian: Voivodina), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (Serbian: Аутономна Покрајина Војводина / Autonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina; see Names in other languages), is an autonomous province of Serbia, located in the northern part of the country, in the Pannonian Plain.

listen); Serbian Cyrillic: Војводина; Pannonian Rusyn: Войводина; Hungarian: Vajdaság [ˈvɒjdɒʃaːɡ]; Slovak and Czech: Vojvodina; Romanian: Voivodina), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (Serbian: Аутономна Покрајина Војводина / Autonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina; see Names in other languages), is an autonomous province of Serbia, located in the northern part of the country, in the Pannonian Plain.

Novi Sad is the largest city and administrative center of Vojvodina and the second-largest city in Serbia. Vojvodina has a population of almost 2 million (nearly 27% of Serbia's population excluding Kosovo).[2] There are some 26 ethnic groups in the province,[3] and six languages are in official use by the provincial administration.[4]

Contents

1 Name

2 History

2.1 Pre-Roman times and Roman rule

2.2 Early Middle Ages and Slavic settlement

2.3 Hungarian rule

2.4 Ottoman rule

2.5 Habsburg rule

2.5.1 Hungarian Crown land (1699-1849)

2.5.2 Austrian Crown land (1849-1860)

2.6 Hungarian rule

2.6.1 Hungarian Crown land (1860-1876)

2.6.2 Counties in the Kingdom of Hungary (1876-1920)

2.7 Kingdom of Yugoslavia, World War II, socialist Yugoslavia

2.8 Contemporary period

3 Geography

4 Politics

5 Demographics

5.1 Largest cities

6 Culture

7 Economy

7.1 Transport

7.2 Tourism

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Name

The term vojvodina in Serbian means a type of duchy – more specifically, a voivodeship. It derives from the word "vojvoda" (See: voivode) which stems from the Proto-Slavic language word "voevoda". Those words are etymologically connected with modern-day words "vojnik" (soldier) and "voditi" (to lead). Its original name (from 1848) was the "Serbian Voivodeship" (Српска Војводина/Srpska Vojvodina) which then became "Voivodeship of Serbia" (Војводство Србија/Vojvodstvo Srbija).

The full official names of the province in all official languages of Vojvodina are:

Serbian: Аутономна Покрајина Војводина / Autonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina

Hungarian: Vajdaság Autonóm Tartomány

Slovak: Autonómna pokrajina Vojvodina

Romanian: Provincia Autonomă Voivodina

Croatian: Autonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina

Pannonian Rusyn: Автономна Покраїна Войводина (Avtonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina)

History

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (February 2012) |

Pre-Roman times and Roman rule

In the Neolithic period, two important archaeological cultures flourished in this area: the Starčevo culture and the Vinča culture. Indo-European peoples first settled in the territory of present-day Vojvodina in 3200 BC. During the Eneolithic period, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, several Indo-European archaeological cultures were centered in or around Vojvodina, including the Vučedol culture, the Vatin culture, and the Bosut culture, among others.

Before the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC, Indo-European peoples of Illyrian, Thracian and Celtic origin inhabited this area. The first states organized in this area were the Celtic State of the Scordisci (3rd century BC-1st century AD) with capital in Singidunum (Belgrade), and the Dacian Kingdom of Burebista (1st century BC).

During Roman rule, Sirmium (modern Sremska Mitrovica) was one of the four capital cities of the Roman Empire, and six Roman Emperors were born in this city or in its surroundings. The city was also the capital of several Roman administrative units, including Pannonia Inferior, Pannonia Secunda, the Diocese of Pannonia, and the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum.

Roman rule lasted until the 5th century, after which the region came into the possession of various peoples and states. While Banat was a part of the Roman province of Dacia, Syrmia belonged to the Roman province of Pannonia. Bačka was not part of the Roman Empire and was populated and ruled by Sarmatian Iazyges.

Early Middle Ages and Slavic settlement

After the Romans were driven away from this region, various Indo-European and Turkic peoples and states ruled in the area. These peoples included Goths, Sarmatians, Huns, Gepids and Avars. For regional history, the largest in importance was a Gepid state, which had its capital in Sirmium. According to the 7th-century Miracles of Saint Demetrius, Avars gave the region of Syrmia to a Bulgar leader named Kuber circa 680. The Bulgars of Kuber moved south with Maurus to Macedonia where they co-operated with Tervel in the 8th century.

Ruins of Arača church

Slavs settled today's Vojvodina in the 6th and 7th centuries,[5] before some of them crossed the rivers Sava and Danube and settled in the Balkans. Slavic tribes that lived in the territory of present-day Vojvodina included Abodrites, Severans, Braničevci and Timočani.

In the 9th century, after the fall of the Avar state, the first forms of Slavic statehood emerged in this area. The first Slavic states that ruled over this region included the Bulgarian Empire, Great Moravia and Ljudevit's Pannonian Duchy. During the Bulgarian administration (9th century), local Bulgarian dukes, Salan and Glad, ruled over the region. Salan's residence was Titel, while that of Glad was possibly in the rumoured rampart of Galad or perhaps in the Kladovo (Gladovo) in eastern Serbia. Glad's descendant was the duke Ahtum, another local ruler from the 11th century who opposed the establishment of Hungarian rule over the region.[citation needed]

In the village of Čelarevo archaeologists have also found traces of people who practised the Judaic religion. Bunardžić dated Avar-Bulgar graves excavated in Čelarevo, containing skulls with Mongolian features and Judaic symbols, to the late 8th and 9th centuries. Erdely and Vilkhnovich consider the graves to belong to the Kabars who eventually broke ties with the Khazar Empire between the 830s and 862. (Three other Khazar tribes joined the Magyars and took part in the Magyar conquest of the Carpathian basin including what is now Vojvodina in 895-907.)[citation needed]

Hungarian rule

Bač Fortress

Following territorial disputes with Byzantine and Bulgarian states, most of Vojvodina became part of the Kingdom of Hungary between 10th and 12th century and remained under Hungarian administration until the 16th century (Following periods of Ottoman and Habsburg administrations, Hungarian political dominance over most of the region was established again in 1867 and over entire region in 1882, after abolition of the Habsburg Military Frontier).[citation needed]

The regional demographic balance started changing in the 11th century when Magyars began to replace the local Slavic population. But from the 14th century, the balance changed again in favour of the Slavs when Serbian refugees fleeing from territories conquered by the Ottoman army settled in the area. Most[6] of the Hungarians left the region during Ottoman conquest and early period of Ottoman administration, so the population of Vojvodina in Ottoman times was predominantly Serbs (who comprised an absolute majority of Vojvodina at the time) and Muslims.[6]

Ottoman rule

After the defeat of the Kingdom of Hungary at Mohács by the Ottoman Empire, the region fell into a period of anarchy and civil wars. In 1526 Jovan Nenad, a leader of Serb mercenaries, established his rule in Bačka, northern Banat and a small part of Syrmia. He created an ephemeral independent state, with Subotica as its capital.

At the peak of his power, Jovan Nenad proclaimed himself Serbian Emperor in Subotica. Taking advantage of the extremely confused military and political situation, the Hungarian noblemen from the region joined forces against him and defeated the Serbian troops in the summer of 1527. Emperor Jovan Nenad was assassinated and his state collapsed. After the fall of emperor's state, the supreme military commander of Jovan Nenad's army, Radoslav Čelnik, established his own temporary state in the region of Syrmia, where he ruled as Ottoman vassal.

A few decades later, the whole region was added to the Ottoman Empire, which ruled over it until the end of the 17th and the first half of the 18th century, when it was incorporated into the Habsburg Monarchy. The Treaty of Karlowitz of 1699, between Holy League and Ottoman Empire, marked the withdrawal of the Ottoman forces from Central Europe, and the supremacy of the Habsburg Empire in that part of the continent. According to the treaty, western part of Vojvodina passed to Habsburgs. Eastern part of it (eastern Syrmia and Province of Tamışvar) remained in Ottoman hands until Austrian conquest in 1716. This new border change is ratified by the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718.

Habsburg rule

Hungarian Crown land (1699-1849)

Blagoveštenski assembly in Sremski Karlovci, 1861

During the Great Serb Migration, Serbs from Ottoman territories settled in the Habsburg Monarchy at the end of the 17th century (in 1690), most of whom settled what is now Hungary, the lesser part settling in western Vojvodina. Therefore, all Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy gained the status of a recognized nation with extensive rights, in exchange for providing a border militia (in the Military Frontier) that could be mobilized against invaders from the south, as well as in case of civil unrest in the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.[citation needed]

At the beginning of Habsburg rule, most of the region was integrated into the Military Frontier, while western parts of Bačka were put under civil administration within the County of Bač. Later, the civil administration was expanded to other (mostly northern) parts of the region, while southern parts remained under military administration. The eastern part of it was held by the Ottomans between 1787–88, during the Russo-Turkish War. In 1716, Vienna temporarily forbade settlement by Hungarians and Jews in the area, while large numbers of German speakers were settled in the region. From 1782, Protestant Hungarians and ethnic Germans settled in larger numbers.[citation needed]

Proclaimed borders of Serbian Vojvodina at the May Assembly (1848) and autonomous Ottoman Principality of Serbia

During the 1848-49 revolutions, Vojvodina was a site of war between Serbs and Hungarians, due to the opposite national conceptions of these two peoples. At the May Assembly in Sremski Karlovci (13–15 May 1848), Serbs declared the constitution of the Serbian Voivodship (Serbian Duchy), a Serbian autonomous region within the Austrian Empire. The Serbian Voivodship consisted of Srem, Bačka, Banat, and Baranja.[citation needed]

The head of the metropolitanate of Sremski Karlovci, Josif Rajačić, was elected patriarch, while Stevan Šupljikac was chosen as first voivod (duke). The ethnic war hit this area perhaps the hardest, with terrible atrocities committed against the civilian populations by both sides.[citation needed]

Austrian Crown land (1849-1860)

Following the Habsburg-Russian and Serb victory over the Hungarians in 1849, a new administrative territory was created in the region in November 1849, in accordance with a decision made by the Austrian emperor. By this decision, the Serbian autonomous region created in 1848 was transformed into the new Austrian crown land known as Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar. It consisted of Banat, Bačka and Srem, excluding the southern parts of these regions which were part of the Military Frontier.[citation needed]

An Austrian governor seated in Temeschwar ruled the area, while the title of Voivod belonged to the emperor himself. The full title of the emperor was "Grand Voivod of the Voivodship of Serbia" (German: Großwoiwode der Woiwodschaft Serbien). German and Illyrian (Serbian) were the official languages of the crown land. In 1860, the new province was abolished and most of it (with exception of Syrmia) was again integrated into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.[citation needed]

Hungarian rule

Hungarian Crown land (1860-1876)

Vojvodina remained Austrian Crown land until 1860, when Emperor Franz Joseph decided that it will be a Hungarian Crown land again.[7] After 1867, the Kingdom of Hungary became one of two self-governing parts of Austria-Hungary, the territory returned again to Hungarian administration.

Counties in the Kingdom of Hungary (1876-1920)

In 1876, a new county system was introduced and the territory was split between Bács-Bodrog, Torontál and Temes counties. The era following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise was a period of economic flourishing, since Kingdom of Hungary had the second fastest growing economy in Europe between 1867–1913, but ethnic relations were strained. According to the 1910 census, the last census conducted in Austria-Hungary, the population of Vojvodina included 510,754 (33.8%) Serbs, 425,672 (28.1%) Hungarians and 324,017 (21.4%) Germans.[citation needed]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia, World War II, socialist Yugoslavia

Novi Sad, at the beginning of 20th century

At the end of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed. On 29 October 1918, Syrmia became a part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On 31 October 1918, the Banat Republic was proclaimed in Timișoara. The government of Hungary recognized its independence, but it was short-lived. On 25 November 1918, the Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci, and other nations of Vojvodina in Novi Sad proclaimed the unification of Vojvodina (Banat, Bačka and Baranja) with the Kingdom of Serbia (The assembly numbered 757 deputies, of which 578 were Serbs, 84 Bunjevci, 62 Slovaks, 21 Rusyn, 6 Germans, 3 Šokci, 2 Croats and 1 Hungarian). One day before this, on 24 November, the Assembly of Syrmia also proclaimed the unification of Syrmia with Serbia. On 1 December 1918, Vojvodina (as part of the Kingdom of Serbia) officially became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci, and other nations of Vojvodina in Novi Sad proclaimed the unification of Vojvodina region with the Kingdom of Serbia, 1918.

Between 1929-41, the region became part of the Danube Banovina, a province of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Its capital city was Novi Sad. Apart from the core territories of Vojvodina and Baranja, it included significant parts of Šumadija and Braničevo regions south of the Danube (but not the capital city of Belgrade).

Between 1941-44, during World War II, Nazi Germany and its allies, Hungary and the Independent State of Croatia, divided and occupied Vojvodina. Bačka and Baranja were annexed by Horthy's Hungary and Syrmia was included into the Independent State of Croatia. A smaller Danube Banovina (including Banat, Šumadija, and Braničevo) existed as part of the area governed by the Military Administration in Serbia. The administrative center of this smaller province was Smederevo. However, Banat itself was a separate autonomous region ruled by its German minority. The occupying powers committed numerous crimes against the civilian population, especially against Serbs, Jews and Roma; the Jewish population of Vojvodina was almost completely killed or deported. In total, Axis (German, Croatian and Hungarian) occupational authorities killed about 50,000 citizens of Vojvodina (mostly Serbs, Jews and Roma) while more than 280,000 people were interned, arrested, violated or tortured.[8]

Axis occupation ended in 1944 and the region was temporarily placed under military administration (1944–45) run by the new communist authorities. During and after the military administration, several thousands of citizens were killed - this affected mostly ethnic Germans, but also one part of Hungarian and Serb populations. Both the war-time Axis occupational authorities and the post-war communist authorities ran concentration/prison camps in the territory of Vojvodina. (see List of concentration and internment camps). While war-time prisoners in these camps were mostly Jews, Serbs and communists, post-war camps were formed for ethnic Germans (Danube Swabians).[citation needed]

Most Vojvodina Germans (about 200,000) fled the region in 1944, together with the defeated German army.[9] Most of those who remained in the region (about 150,000) were sent to some of the villages cordoned off as prisons. It is estimated that some 48,447 Germans died in the camps from disease, hunger, malnutrition, mistreatment, and cold.[10] Some 8,049 Germans were killed by partisans during military administration in Vojvodina after October 1944.[11][12] It has also been estimated that post-war communist authorities killed some 15,000-20,000[13][14] Hungarians and some 23,000-24,000[15] Serbs during Communist purges in Serbia in 1944–45. According to Professor Dragoljub Živković, some 47,000 ethnic Serbs were murdered in Vojvodina between 1941-48. About half were killed by occupational Axis forces and the other half by the post-war Communist authorities.[15]

The region was politically restored in 1944 (incorporating Syrmia, Banat, Bačka, and Baranja) and became an autonomous province of Serbia in 1945. Instead of the previous name (Danube Banovina), the region regained its historical name of Vojvodina, while its capital city remained Novi Sad. When the final borders of Vojvodina were defined, Baranja was assigned to Croatia, while the northern part of the Mačva region was assigned to Vojvodina.[citation needed]

At first, the province enjoyed only a small level of autonomy within Serbia, but it gained extensive rights of self-rule under the 1974 Yugoslav constitution, which gave both Kosovo and Vojvodina de facto veto power in the Serbian and Yugoslav parliaments, as changes to their status could not be made without the consent of the two Provincial Assemblies.[citation needed]

The 1974 Serbian constitution, adopted at the same time, reiterated that "the Socialist Republic of Serbia comprises the Socialist Autonomous Province of Vojvodina and the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, which originated in the common struggle of nations and nationalities of Yugoslavia in the National Liberation War (the Second World War) and socialist revolution".[citation needed]

Under the rule of Serbian president Slobodan Milošević and following a series of protests against Vojvodina's party leadership during the summer and autumn of 1988, which forced it to resign and eventually accept Serbia's constitutional amendments that practically dismissed the autonomy of the provinces in Serbia, Vojvodina and Kosovo finally lost elements of statehood in September 1990 when the new constitution of the Republic of Serbia was adopted.

Vojvodina was still referred to as an autonomous province of Serbia, but most of its autonomous powers – including, crucially, its vote on the Yugoslav collective presidency – were transferred to the control of Belgrade. The province, however, still had its own parliament and government and some other autonomous functions as well.[16]

Contemporary period

The fall of Milošević in 2000 created a new political climate in Vojvodina. Following talks between the political parties, the level of the province's autonomy was somewhat increased by the omnibus law in 2002. The Vojvodina provincial assembly adopted a new statute on 15 October 2008, which, partly amended, was approved by the Parliament of Serbia.

Geography

National park Fruška Gora

Palić lake

Vojvodina is situated in the northern quarter of Serbia, in the southeast part of the Pannonian Plain, the plain that remained when the Pliocene Pannonian Sea dried out. As a consequence of this, Vojvodina is rich in fertile loamy loess soil, covered with a layer of chernozem. The region is divided by the Danube and Tisa rivers into: Bačka in the northwest, Banat in the east and Syrmia (Srem) in the southwest. A small part of the Mačva region is also located in Vojvodina, in the Srem District.[citation needed]

Today, the western part of Syrmia is in Croatia, the northern part of Bačka is in Hungary, the eastern part of Banat is in Romania (with a small piece in Hungary), while Baranja (which is between the Danube and the Drava) is in Hungary and Croatia. Vojvodina has a total surface area of 21,500 km2 (8,300 sq mi).[17] Vojvodina is also part of the Danube-Kris-Mures-Tisa euroregion. The Gudurica peak (Gudurički vrh) on the Vršac Mountains, is the highest peak in Vojvodina, at an altitude of 641 m above sea level.[citation needed]

Politics

Banovina Palace, the seat of the Provincial Government of Vojvodina, at night

The Assembly of Vojvodina is the provincial legislature composed of 120 proportionally elected members. The current members were elected in the 2016 provincial elections. The Government of Vojvodina is the executive administrative body composed of a president and cabinet ministers.[18]

The current ruling coalition in the Vojvodina parliament is composed of the following political parties: Serbian Progressive Party, Socialist Party of Serbia and Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians. The current president of Vojvodinian government is Igor Mirović (Serbian Progressive Party), while the president of the provincial Assembly is István Pásztor (Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians).[citation needed]

Vojvodina is divided into seven districts. They are regional centers of state authority, but have no powers of their own; they present purely administrative divisions. The seven districts are further subdivided into 37 municipalities and the 8 cities of Kikinda, Novi Sad, Subotica, Zrenjanin, Pančevo, Sombor, Sremska Mitrovica, and Vršac.

Districts, municipalities and cities of Vojvodina .mw-parser-output div.columns-2 div.column{float:left;width:50%;min-width:300px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-3 div.column{float:left;width:33.3%;min-width:200px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-4 div.column{float:left;width:25%;min-width:150px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-5 div.column{float:left;width:20%;min-width:120px}

| North Bačka West Bačka South Bačka Syrmia | North Banat Central Banat South Banat |

District | District seat with city status | Municipalities | Area (km²) | Population (2011) |

Central Banat | Zrenjanin | Novi Bečej, Nova Crnja, Sečanj, Žitište | 3,256 | 187,667 |

North Bačka | Subotica | Bačka Topola, Mali Iđoš | 1,784 | 186,906 |

North Banat | Kikinda | Ada, Čoka, Kanjiža, Novi Kneževac, Senta | 2,329 | 147,770 |

South Bačka | Novi Sad | Bač, Bačka Palanka, Bački Petrovac, Bečej, Beočin, Vrbas, Srbobran, Sremski Karlovci, Temerin, Titel, Žabalj | 4,016 | 615,371 |

South Banat | Pančevo | Alibunar, Bela Crkva, Kovačica, Kovin, Opovo, Plandište, City of Vršac | 4,245 | 293,730 |

Syrmia | Sremska Mitrovica | Inđija, Irig, Pećinci, Ruma, Šid, Stara Pazova | 3,486 | 312,278 |

West Bačka | Sombor | Apatin, Kula, Odžaci | 2,420 | 188,087 |

Total | 21,500 | 1,931,809 | ||

Demographics

Ethnic map of Vojvodina (settlement data)

Language map of Vojvodina (municipality data)

Religion map of Vojvodina (municipality data)

Vojvodina is more diverse than the rest of Serbia with more than 25 ethnic groups and six languages which are in the official use by the provincial administration.[19]

Population by ethnicity:[20]

Number | % | |

TOTAL | 1,931,809 | 100 |

Serbs | 1,289,635 | 66.76 |

Hungarians | 251,136 | 13.00 |

Slovaks | 50,321 | 2.60 |

Croats | 47,033 | 2.43 |

Romani | 42,391 | 2.19 |

Romanians | 25,410 | 1.32 |

Montenegrins | 22,141 | 1.15 |

Bunjevci | 16,469 | 0.85 |

Rusyns | 13,928 | 0.72 |

Yugoslavs | 12,176 | 0.63 |

Macedonians | 10,392 | 0.54 |

Ukrainians | 4,202 | 0.22 |

Muslims (by nationality) | 3,360 | 0.17 |

Germans | 3,272 | 0.17 |

Albanians | 2,251 | 0.12 |

Slovenes | 1,815 | 0.09 |

Bulgarians | 1,489 | 0.08 |

Goranis | 1,179 | 0.06 |

Russians | 1,173 | 0.06 |

Bosniaks | 780 | 0.04 |

Vlachs | 170 | 0.01 |

| Others | 6,710 | 0.35 |

Regional affiliation | 28,567 | 1.48 |

| Undeclared | 81,018 | 4.19 |

| Unknown | 14,791 | 0.77 |

Population by mother tongue:

Number | % | |

Serbian language | 1,485,791 | 76.91 |

Hungarian language | 241,164 | 12.48 |

Slovak language | 47,760 | 2.47 |

Romani language | 27,430 | 1.42 |

Romanian language | 24,133 | 1.25 |

Croatian language | 14,576 | 0.75 |

Rusyn language | 11,154 | 0.58 |

Bunjevac language | 6,821 | 0.35 |

Albanian language | 3,844 | 0.2 |

Macedonian language | 3,694 | 0.19 |

Montenegrin language | 1,193 | 0.06 |

Population by religion:

Number | % | |

Eastern Orthodox Christians | 1,357,317 | 70.25 |

Catholics (Roman Catholic and Eastern Rite) | 336,691 | 17.43 |

Protestants | 64,029 | 3.31 |

Muslims | 14,026 | 0.74 |

| Oriental religions (Buddhism, Hinduism etc.) | 394 | 0.02 |

Jews | 254 | 0.01 |

| Others | 647 | 0.03 |

Atheists | 25,906 | 1.34 |

| Undeclared | 106,740 | 5.53 |

| Unknown | 18,205 | 0.94 |

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Vojvodina Statistical Office of Serbia – 2011 census[permanent dead link] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

Novi Sad  Subotica | 1 | Novi Sad | South Bačka | 277,522 | 11 | Indjija | Syrmia | 26,025 |  Zrenjanin  Pančevo |

| 2 | Subotica | North Bačka | 105,681 | 12 | Vrbas | South Bačka | 24,112 | ||

| 3 | Zrenjanin | Central Banat | 76,511 | 13 | Bečej | South Bačka | 23,895 | ||

| 4 | Pančevo | South Banat | 76,203 | 14 | Temerin | South Bačka | 19,661 | ||

| 5 | Sombor | West Bačka | 47,623 | 15 | Senta | North Banat | 18,704 | ||

| 6 | Kikinda | North Banat | 38,065 | 16 | Futog | South Bačka | 18,641 | ||

| 7 | Sremska Mitrovica | Syrmia | 37,751 | 17 | Stara Pazova | Syrmia | 18,602 | ||

| 8 | Vršac | South Banat | 36,040 | 18 | Kula | West Bačka | 17,866 | ||

| 9 | Ruma | Syrmia | 30,076 | 19 | Veternik | South Bačka | 17,454 | ||

| 10 | Bačka Palanka | South Bačka | 28,239 | 20 | Apatin | West Bačka | 17,411 | ||

Culture

National Theatre in Subotica (1852), the second oldest professional theatre in Serbia.

Iriški Venac Tower, Fruška Gora

There are two daily newspapers published in Vojvodina, Dnevnik in Serbian and Magyar Szó in Hungarian. Monthly and weekly publications in minority languages include Hrvatska riječ ("Croatian Word") in Croatian, Hlas Ľudu ("The Voice of the People") in Slovak, Libertatea ("Freedom") in Romanian, and Руске слово ("Rusyn Word") in Rusyn. There is also Bunjevačke novine ("The Bunjevac newspaper") in Bunjevac.

Public Broadcasting Service of Vojvodina was founded in 1974 as Radio Television of Novi Sad, as an equal member of the association of JRT – Yugoslav Radio Television. Radio Novi Sad's first broadcast was on November 29, 1949. During the NATO bombing in the spring of 1999, the RT Novi Sad building of 20 thousand square meters was completely destroyed along with its basic production and technical premises . The Venac terrestrial broadcasting site was heavily damaged.

The Radio-Television of Vojvodina produces and broadcasts regional programming on two channels, RTV1 (Serbian language) and RTV2 (minority languages), and three radio frequencies: Radio Novi Sad 1 (Serbian), Radio Novi Sad 2 (Hungarian), Radio Novi Sad 3 (other minority communities).[21]

Economy

Vojvodina is known as Serbia's breadbasket

The economy of Vojvodina is largely based on developed food industry and fertile agricultural soil. Agriculture is a priority sector in Vojvodina. Traditionally, it has always been a significant part of the local economy and a generator of positive results, due to the abundance of fertile agricultural land which makes up 84% of its territory. The share of agribusiness in the total industrial production is 40%, that is 30% in the total exports of Vojvodina.

The metal industry of Vojvodina has a long tradition and consists of smaller metal processing companies for components manufacturing and, to a lesser extent, of original equipment manufacturers (OEM) with their own brand name products. Vojvodina Metal Cluster gathers 116 companies with 6,300 employees. Other branches of industry are also developed such as the chemical industry, electrical industry, oil industry and construction industry. In the past decade, ICT sector has been growing rapidly and has taken significant role in Vojvodina's economic development.

High- tech sector is a fast-growing sector in Vojvodina. Software development represents the main source of revenue, particularly development of ERP solutions, Java applications and mobile applications. IT sector companies mainly deal with software outsourcing, based on demands of international clients or with development of their own software products for purposes of domestic and international market.

Vojvodina pays particular attention to interregional and cross-border economic cooperation, as well as to implementation of priorities defined within the EU Strategy for the Danube Region.[1]

Some of the companies from Vojvodina:

- Naftna Industrija Srbije

- Srbijagas

- HIP Petrohemija

- Apatin Brewery

- Novosadski sajam

Vojvodina promotes its investment potentials through the Vojvodina Investment Promotion (VIP) agency, which was founded by the Parliament of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina.

Transport

There are many important roads which pass through Vojvodina. First of all, the motorway A1 motorway which goes from Central Europe and the Horgos border crossing to Hungary, via Novi Sad to Belgrade and further to the southeast toward Niš, where it branches: one way leads east to the border with Bulgaria; the other to the south, towards Greece. Motorway A3 in Srem separates the west, towards the neighboring Croatia and further to Western Europe. There is also a network of regional and local roads and railway lines.

The three largest rivers in Vojvodina are navigable stream. Danube River with a length of 588 kilometers and its tributaries Tisa (168 km), Sava (206 km) and Bega (75 km). Among them was dug extensive network of irrigation canals, drainage and transport, with a total length of 939 km, of which 673 km navigable.

Tourism

Tourist destinations in Vojvodina include well known Orthodox monasteries on Fruška Gora mountain, numerous hunting grounds, cultural-historical monuments, different folklores, interesting galleries and museums, plain landscapes with a lot of greenery, big rivers, canals and lakes, sandy terrain Deliblatska Peščara ("the European Sahara"), etc.

In the last few years, Exit has been very popular among the European summer music festivals.[22]

See also

- Vojvodina Autonomist Movement

- Rinflajš

References

^ ab "Autonomous Province of Vojvodina". vojvodina.gov.rs. Retrieved 26 March 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Покрајинска влада". vojvodina.gov.rs. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

^ "Serbian Government - Official Presentation". serbia.gov.rs. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

^ "Beogradski centar za ljudska prava - Belgrade Centre for Human Rights". bgcentar.org.rs. 29 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

^ "Slovenski grobovi uz reku Galadsku". Blic.rs. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

^ ab "Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin". google.rs. pp. 140, 155.

^ Geert-Hinrich Ahrens (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press Series. p. 243. ISBN 9780801885570.

^ Popov, Dr Dušan, Vojvodina, Enciklopedija Novog Sada, sveska 5, Novi Sad, 1996, pg. 196.

^ Dragomir Jankov, Vojvodina - propadanje jednog regiona, Novi Sad, 2004, page 76.

^ "Cine a fost Baba Novac, credinciosul general al lui Mihai Viteazul, ucis de unguri în chinuri groaznice şi devorat de corbi".

^ Stefanović, Nenad. Jedan svet na Dunavu, Beograd, 2003, page 133.

^ Janjetović, Zoran. Between Hitler and Tito, 2005.

^ "Commemoration Held On 70th Anniversary Of Vojvodina Hungarian Massacre In Szeged". Hungary Today.

^ Jankov, Dragomir. Vojvodina – propadanje jednog regiona, Novi Sad, 2004, page 78.

^ ab "[sim] Srbe podjednako ubijali okupator i i "oslobodioci"". mail-archive.com. 14 January 2009.

^ Đorđe Tomić (28 November 2014). ""Phantomgrenzen" in Zeiten des Umbruchs – die Autonomieidee in der Vojvodina der 1990er Jahre" (PDF). Dissertation. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2015.

^ "Vojvodina". Encyclopædia Britannica.

^ "Government of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina". vojvodina.gov.rs. Archived from the original on 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

^ Johnstone, Sarah (2007). Europe on a shoestring. Lonely Planet. p. 981. ISBN 978-1-74104-591-8.

^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). Pod2.stat.gov.rs. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

^ "About Us". Radio-Television of Vojvodina. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ "Vojvodina online - Tourism Organisation of Vojvodina". vojvodinaonline.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vojvodina. |

(in English) (in Serbian) Government of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina

(in English) (in Serbian) Assembly of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina

(in English) (in Serbian) Provincial Secretariat for Regional and International Cooperation

(in English) (in Serbian) Tourism organization of Vojvodina

(in English) (in Serbian) VojvodinaCafe - All about Vojvodina

- Useful information about Vojvodina, Parks of Nature, River Expedition, Wine Trails, Cities, Etno, Adventure and more

- Interactive map of Novi Sad

- Atlas of Vojvodina (Wikimedia Commons)

Statistical information about municipalities of Vojvodina[permanent dead link]

- List of largest cities of Vojvodina

(in Hungarian) The encyclopedia of Vojvodina