Château de Chambord

| Château de Chambord | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Château de Chambord | |

Location within France | |

| General information | |

| Status | Extant |

| Architectural style | French Renaissance Classical Renaissance |

| Location | Chambord, Loir-et-Cher, France |

| Address | Chateau 41250, Chambord, France |

| Coordinates | 47°36′59″N 1°31′01″E / 47.616342°N 1.516962°E / 47.616342; 1.516962Coordinates: 47°36′59″N 1°31′01″E / 47.616342°N 1.516962°E / 47.616342; 1.516962 |

| Construction started | 1519 |

| Completed | 1547 |

| Height | 56m |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Domenico da Cortona |

| Structural engineer | Pierre Nepveu |

| Website | |

| Official site of the Chateau de Chambord | |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | The Loire Valley between Sully-sur-Loire and Chalonnes, previously inscribed as Chateau and Estate of Chambord |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, vi |

| Designated | 1981 (5th session) |

| Reference no. | 933 |

| State Party | France |

| Region | Europe |

The Château de Chambord (French pronunciation: [ʃɑto də ʃɑ̃bɔʁ]) in Chambord, Loir-et-Cher, France, is one of the most recognisable châteaux in the world because of its very distinctive French Renaissance architecture which blends traditional French medieval forms with classical Renaissance structures. The building, which was never completed, was constructed by King Francis I of France.

Chambord is the largest château in the Loire Valley; it was built to serve as a hunting lodge for Francis I, who maintained his royal residences at the Château de Blois and Amboise. The original design of the Château de Chambord is attributed, though with some doubt, to Domenico da Cortona; Leonardo da Vinci may also have been involved.

Chambord was altered considerably during the twenty-eight years of its construction (1519–1547), during which it was overseen on-site by Pierre Nepveu. With the château nearing completion, Francis showed off his enormous symbol of wealth and power by hosting his old archrival, Emperor Charles V, at Chambord.

In 1792, in the wake of the French Revolution, some of the furnishings were sold and timber removed. For a time the building was left abandoned, though in the 19th century some attempts were made at restoration. During the Second World War, art works from the collections of the Louvre and the Château de Compiègne were moved to the Château de Chambord. The château is now open to the public, receiving 700,000 visitors in 2007. Flooding in June 2016 damaged the grounds but not the château itself.

Contents

1 Architecture

2 History

2.1 Royal ownership

2.2 French Revolution and modern history

3 Influence

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Architecture

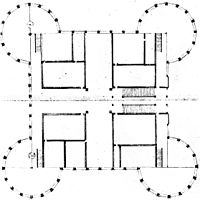

Plan of the château as engraved by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1576)

The château and decorative moat, viewed from the North-West (2015)

Châteaux in the 16th century departed from castle architecture;[nb 1] while they were off-shoots of castles, with features commonly associated with them, they did not have serious defences. Extensive gardens and water features, such as a moat, were common amongst châteaux from this period. Chambord is no exception to this pattern. The layout is reminiscent of a typical castle with a keep, corner towers, and defended by a moat.[3] Built in Renaissance style, the internal layout is an early example of the French and Italian style of grouping rooms into self-contained suites, a departure from the medieval style of corridor rooms.[4][nb 2] The massive château is composed of a central keep with four immense bastion towers at the corners. The keep also forms part of the front wall of a larger compound with two more large towers. Bases for a possible further two towers are found at the rear, but these were never developed, and remain the same height as the wall. The château features 440 rooms, 282 fireplaces, and 84 staircases. Four rectangular vaulted hallways on each floor form a cross-shape.

The château was never intended to provide any form of defence from enemies; consequently the walls, towers and partial moat are decorative, and even at the time were an anachronism. Some elements of the architecture—open windows, loggia, and a vast outdoor area at the top—borrowed from the Italian Renaissance architecture—are less practical in cold and damp northern France.

The elaborately developed roof line. It should be noted that the keep's façade is asymmetrical, with the exception of the northwest façade, latterly revised, when the two wings were added to the château.

The roofscape of Chambord contrasts with the masses of its masonry and has often been compared with the skyline of a town:[6] it shows eleven kinds of towers and three types of chimneys, without symmetry, framed at the corners by the massive towers. The design parallels are north Italian and Leonardesque. Writer Henry James remarked "the towers, cupolas, the gables, the lanterns, the chimneys, look more like the spires of a city than the salient points of a single building."[7][8]

The double-spiral staircase

One of the architectural highlights is the spectacular open double-spiral staircase that is the centrepiece of the château. The two spirals ascend the three floors without ever meeting, illuminated from above by a sort of light house at the highest point of the château. There are suggestions that Leonardo da Vinci may have designed the staircase, but this has not been confirmed. Writer John Evelyn said of the staircase "it is devised with four [sic] entries or ascents, which cross one another, so that though four persons meet, they never come in sight, but by small loopholes, till they land. It consists of 274 steps (as I remember), and is an extraordinary work, but of far greater expense than use or beauty."[8]

The château also features 128 metres of façade, more than 800 sculpted columns and an elaborately decorated roof. When Francis I commissioned the construction of Chambord, he wanted it to look like the skyline of Constantinople.

The château is surrounded by a 52.5-square-kilometre (13,000-acre) wooded park and game reserve maintained with red deer, enclosed by a 31-kilometre (19-mile) wall. The king's plan to divert the Loire to surround the château came about only in a novel; Amadis of Gaul, which Francis had translated. In the novel the château is referred to as the Palace of Firm Isle.

Chambord's towers are atypical of French contemporary design in that they lack turrets and spires. In the opinion of author Tanaka, who suggests Leonardo da Vinci influenced the château's design, they are closer in design to minarets of 15th-century Milan.[6]

The design and architecture of the château inspired William Henry Crossland for his design of what is known as the Founder's building at Royal Holloway, University of London. The Founder's Building features very similar towers and layout but was built using red bricks.

History

Royal ownership

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Félibien's drawings based on a wooden model

Who designed the Château de Chambord is a matter of controversy.[9] The original design is attributed, though with several doubts, to Domenico da Cortona, whose wooden model for the design survived long enough to be drawn by André Félibien in the 17th century.[10] In the drawings of the model, the main staircase of the keep is shown with two straight, parallel flights of steps separated by a passage and is located in one of the arms of the cross. According to Jean Guillaume, this Italian design was later replaced with the centrally located spiral staircase, which is similar to that at Blois, and a design more compatible with the French preference for spectacular grand staircases. However, "at the same time the result was also a triumph of the centralized layout—itself a wholly Italian element."[11] In 1913 Marcel Reymond suggested[12] that Leonardo da Vinci, a guest of Francis at Clos Lucé near Amboise, was responsible for the original design, which reflects Leonardo's plans for a château at Romorantin for the King's mother, and his interests in central planning and double-spiral staircases; the discussion has not yet concluded,[13] although most scholars now agree that Leonardo was at least responsible for the design of the central staircase.[14]

Archeological findings by Jean-Sylvain Caillou & Dominic Hofbauer have established that the lack of symmetry of some facades derives from an original design, abandoned shortly after the construction began, and which ground plan was organised around the central staircase following a central gyratory symmetry.[15] Such a rotative design has no equivalent in architecture at this period of history, and appears reminiscent of Leonardo Da Vinci's works on hydraulic turbines, or the helicopter. Had it been respected, it is believed that this unique building could have featured the quadruple-spiral open staircase, strangely described by John Evelyn and Andrea Palladio although it was never built.

Regardless of who designed the château, on 6 September 1519 Francis Pombriant was ordered to begin construction of the Château de Chambord.[16] The work was interrupted by the Italian War of 1521–1526, and work was slowed by dwindling royal funds[17] and difficulties in laying the structure's foundations. By 1524, the walls were barely above ground level.[16] Building resumed in September 1526, at which point 1,800 workers were employed building the château. At the time of the death of King Francis I in 1547, the work had cost 444,070 livres.[17]

Painting by Pierre-Denis Martin of Château de Chambord in 1722

The château was built to act as a hunting lodge for King Francis I;[4] however, the king spent barely seven weeks there in total, that time consisting of short hunting visits. As the château had been constructed with the purpose of short stays, it was not practical to live in on a longer-term basis. The massive rooms, open windows and high ceilings meant heating was impractical. Similarly, as the château was not surrounded by a village or estate, there was no immediate source of food other than game. This meant that all food had to be brought with the group, typically numbering up to 2,000 people at a time.

As a result of all the above, the château was completely unfurnished during this period. All furniture, wall coverings, eating implements and so forth were brought specifically for each hunting trip, a major logistical exercise. It is for this reason that much furniture from the era was built to be disassembled to facilitate transportation. After Francis died of a heart attack in 1547, the château was not used for almost a century.

For more than 80 years after the death of King Francis I, French kings abandoned the château, allowing it to fall into decay. Finally, in 1639 King Louis XIII gave it to his brother, Gaston d'Orléans, who saved the château from ruin by carrying out much restoration work.

Louis XIV's ceremonial bedroom

King Louis XIV had the great keep restored and furnished the royal apartments. The king then added a 1,200-horse stable, enabling him to use the château as a hunting lodge and a place to entertain a few weeks each year. Nonetheless, Louis XIV abandoned the château in 1685.[18]

From 1725 to 1733, Stanislas Leszczyński (Stanislas I), the deposed King of Poland and father-in-law of King Louis XV, lived at Chambord. In 1745, as a reward for valour, the king gave the château to Maurice de Saxe, Marshal of France who installed his military regiment there.[19] Maurice de Saxe died in 1750 and once again the colossal château sat empty for many years.

French Revolution and modern history

On the second floor

In 1792, the Revolutionary government ordered the sale of the furnishings; the wall panellings were removed and even floors were taken up and sold for the value of their timber, and, according to M de la Saussaye,[20] the panelled doors were burned to keep the rooms warm during the sales; the empty château was left abandoned until Napoleon Bonaparte gave it to his subordinate, Louis Alexandre Berthier. The château was subsequently purchased from his widow for the infant Duke of Bordeaux, Henri Charles Dieudonné (1820–1883) who took the title Comte de Chambord. A brief attempt at restoration and occupation was made by his grandfather King Charles X (1824–1830) but in 1830 both were exiled. In Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea, published in the 1830s, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow remarked on the dilapidation that had set in: "all is mournful and deserted. The grass has overgrown the pavement of the courtyard, and the rude sculpture upon the walls is broken and defaced".[21] During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) the château was used as a field hospital.

The final attempt to make use of the colossus came from the Comte de Chambord but after the Comte died in 1883, the château was left to his sister's heirs, the titular Dukes of Parma, then resident in Austria. First left to Robert, Duke of Parma, who died in 1907 and after him, Elias, Prince of Parma. Any attempts at restoration ended with the onset of World War I in 1914. The Château de Chambord was confiscated as enemy property in 1915, but the family of the Duke of Parma sued to recover it, and that suit was not settled until 1932; restoration work was not begun until a few years after World War II ended in 1945.[citation needed] The Château and surrounding areas, some 5,440 hectares (13,400 acres; 21.0 sq mi), have belonged to the French state since 1930.[22]

Today, the Château de Chambord is a popular tourist attraction.

In 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, the art collections of the Louvre and Compiègne museums (including the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo) were stored at the Château de Chambord. An American B-24 Liberator bomber crashed onto the château lawn on 22 June 1944.[23] The image of the château has been widely used to sell commodities from chocolate to alcohol and from porcelain to alarm clocks; combined with the various written accounts of visitors, this made Chambord one of the best known examples of France's architectural history.[24] Today, Chambord is a major tourist attraction, and in 2007 around 700,000 people visited the château.[21]

After unusually heavy rainfall, Chambord was closed to the public from 1 to 6 June 2016. The river Cosson, a tributary of the Loire, flooded its banks and the chateau's moat. Drone photography documented some of the peak flooding.[25] The French Patrimony Foundation described effects of the flooding on Chambord's 13,000-acre property. The 20-mile wall around the chateaux was breached at several points, metal gates were torn from their framing, and roads were damaged. Also, trees were uprooted and certain electrical and fire protection systems were put out of order. However, the chateau itself and its collections reportedly were undamaged. The foundation observed that paradoxically the natural disaster effected Francis I's vision that Chambord appear to rise from the waters as if it were diverting the Loire.[26] Repairs are expected to cost upwards of a quarter-million dollars.[27]

Influence

The Founder's Building at Royal Holloway, University of London, designed by William Henry Crossland, was inspired by the Château de Chambord.[28] The main building of Fettes College in Edinburgh, designed by David Bryce in 1870,[29] also contains decorative quotations from the Château de Chambord.[citation needed]

References

Notes

^ Although château and castle derive from the Latin castellum,[1] their meaning is different. In French château-fort refers to a castle, while château more properly describes a country house.[2]

^ Viollet-le-Duc, however, in his Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française (1885) found that there was "nothing Italianate [about Chambord] ..., in thought or in form".[5]

Footnotes

^ Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 6

^ Thompson 1994, p. 1

^ Thompson 1994, pp. 117–120

^ ab Yarwood 1974, p. 323

^ Viollet-le-Duc 1875, p. 189, quoted in Tanaka 1992, p. 85

^ ab Tanaka 1992, p. 96

^ James, Henry (1907) [1900]. A Little Tour in France (2nd ed.). London: William Heinemann. p. 40..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Quoted in Garrett 2010, p. 78

^ Tanaka 1992, p. 85

^ Félibien 1681, pp. 28–29 (Félibien's description of the model).

^ Guillaume 1996, p. 416.

^ Reymond 1913

^ Heydenreich 1952; Tanaka 1992

^ Hanser 2006, p. 47.

^ www.chambord-archeo.com

^ ab Heydenreich 1952, p. 282

^ ab Tanaka 1992, pp. 92–93

^ Chirol & Seydoux 1992, p. 53

^ Boucher 1980, p. 34

^ Saussaye, Le Château de Chambord (Blois) 1865 etc.

^ ab Quoted in Garrett 2010, p. xxii

^ "Presentation". Chambord.org. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

^ "Liberator 22 juin 1944 – Chambord – Aérostèles". Aerosteles.hydroretro.net. 31 May 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

^ Garrett 2010, pp. 78–79

^ Kelsey D. Atherton (3 June 2016). "DRONE FILMS FLOODED FRENCH CASTLE". popsci.com. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

^ "Sauvegarde Du Domaine De Chambord Après Inondations". Fondation du Patrimoine (in French).

^ http://m.france24.com/en/20160608-video-france-famed-chateau-de-chambord-heavily-damaged-floods

^ Original features Times Higher Education. 5 February 2009

^ Fettes College: The Building. Retrieved 21 March 2009

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Boucher, J.J. (1980), Chambord (in French), Fernand Lanore

Chirol, Serge; Seydoux, Philippe (1992), Chateaux of the Val de Loire, Vendôme Press

Creighton, Oliver; Higham, Robert (2003), Medieval Castles, Shire Archaeology, ISBN 0-7478-0546-6

Félibien, André (1681). Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des maisons royales, published for the first time from the manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale in 1874. Paris: J. Baur. Copy at Google Books.

Garrett, Martin (2010), The Loire: a Cultural History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-976839-4

- Guillaume, Jean (1996). "Chambord, château of", vol. 6, pp. 415–417, in The Dictionary of Art, edited by Jane Turner, reprinted with minor corrections in 1998. New York: Grove.

ISBN 9781884446009. - Jean-Sylvain Caillou et Dominic Hofbauer, Chambord, le projet perdu de 1519, Archéa, 2007, 64 p.

- Hanser, David A. (2006). Architecture of France. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

ISBN 978-0-313-31902-0.

Heydenreich, Ludwig H. (October 1952), "Leonardo da Vinci, Architect of Francis I", The Burlington Magazine, 94 (595): 277–285, JSTOR 870959

Reymond, Marcel (June 1913), "Leonardo da Vinci, architect de Chambord", Gazette des Beaux-Arts: 413–460

Tanaka, Hidemichi (1992), "Leonardo da Vinci, Architect of Chambord?", Artibus et Historiae, 13 (25): 85–102, doi:10.2307/1483458, JSTOR 1483458

Thompson, M. W. (1994) [1987], The Decline of the Castle, Magna Books, ISBN 1-85422-608-8

Viollet-le-Duc, Eugene (1875), Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle, 3

Yarwood, Doreen (1974), The Architecture of Europe, London: B. T. Batsford

Further reading

Gebbelin, François (1927), Les Châteaux de la Renaissance

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Château de Chambord. |

- Château de Chambord

- Programme archéologique de Chambord

Rendez-vous at the National Domain of Chambord – Official website for tourism in France (in English)

360° Panoramas of Le Château de Chambord' by the Media Center for Art History, Columbia University