Durand Line

| Durand Line | |

|---|---|

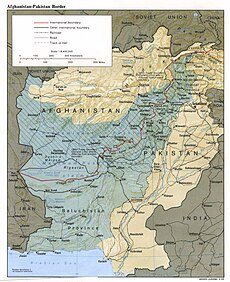

Political map of the Durand Line | |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 2,430 kilometres (1,510 mi) |

| History | |

| Treaties |

|

The Durand Line (Pashto: د ډیورنډ کرښه) is the 2,430-kilometre (1,510 mi) international border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. It was established in 1896 between Sir Mortimer Durand, a British diplomat and civil servant of the British Raj, and Abdur Rahman Khan, the Afghan Amir, to fix the limit of their respective spheres of influence and improve diplomatic relations and trade. Afghanistan was considered by the British as an independent state at the time, although the British controlled its foreign affairs and diplomatic relations.

The single-page agreement, dated 12 November 1893, contains seven short articles, including a commitment not to exercise interference beyond the Durand Line.[1] A joint British-Afghan demarcation survey took place starting from 1894, covering some 800 miles of the border.[2][3] Established towards the close of the "Great Game", the resulting line established Afghanistan as a buffer zone between British and Russian interests in the region.[4] The line, as slightly modified by the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1919, was inherited by Pakistan in 1947 following its independence.

The Durand Line cuts through the Pashtun tribal areas and further south through the Balochistan region, politically dividing ethnic Pashtuns, as well as the Baloch and other ethnic groups, who live on both sides of the border. It demarcates Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan and Gilgit-Baltistan of northern and western Pakistan from the northeastern and southern provinces of Afghanistan. From a geopolitical and geostrategic perspective, it has been described as one of the most dangerous borders in the world.[5][6][7][8]

Although the Durand Line is recognized as the western border of Pakistan, it remains largely unrecognized by Afghanistan.[9][10][11][12][13] In 2017, amid cross-border tensions, former Afghan President Hamid Karzai said that Afghanistan will "never recognise" the Durand Line as the international border between the two countries.[14]

Contents

1 Historical background

1.1 Demarcation surveys on the Durand Line

1.2 Cultural impact of the Durand Line

1.3 British Indian Empire declares war on Afghanistan

1.4 Territorial dispute between Afghanistan and Pakistan

2 Contemporary era

2.1 Recent border conflicts

2.2 Trench being built alongside the border

2.3 2017 border closures

2.4 India-Afghanistan border crossings

3 See also

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Historical background

Arachosia and the Pactyans during the 1st millennium BC

The area through which the Durand Line runs has been inhabited by the indigenous Pashtuns[15] since ancient times, at least since 500 B.C. The Greek historian Herodotus mentioned a people called Pactyans living in and around Arachosia as early as the 1st millennium BC.[16] The Baloch tribes inhabit the southern end of the line, which runs in the Balochistan region that separates the ethnic Baloch people.

Arab Muslims conquered the area in the 7th century and introduced Islam to the Pashtuns. It is believed that some of the early Arabs also settled among the Pashtuns in the Sulaiman Mountains.[17] It is important to note that these Pashtuns were historically known as "Afghans" and are believed to be mentioned by that name in Arabic chronicles as early as the 10th century.[18] The Pashtun area (known today as the "Pashtunistan" region) fell within the Ghaznavid Empire in the 10th century followed by the Ghurids, Timurids, Mughals, Hotakis, and finally by the Durranis.[19]

Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, British diplomat and civil servant of colonial British India. The Durand Line is named in his honour.

In 1839, during the First Anglo-Afghan War, British-led Indian forces invaded Afghanistan and initiated a war with the Afghan rulers. Two years later, in 1842, the British were defeated and the war ended. The British again invaded Afghanistan in 1878, during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, withdrawing a couple of years later after attaining some geopolitical objectives. During this war, the Treaty of Gandamak was signed, ceding control of various frontier areas to the British Empire.

In 1893, Mortimer Durand was dispatched to Kabul by the government of British India to sign an agreement with Amir Abdur Rahman Khan for fixing the limits of their respective spheres of influence as well as improving diplomatic relations and trade. On November 12, 1893, the Durand Line Agreement was reached.[1] The two parties later camped at Parachinar, a small town near Khost in Afghanistan, which is now part of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan, to delineate the frontier.[citation needed]

From the British side, the camp was attended by Mortimer Durand and Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum, Political Agent Khyber Agency representing the British Viceroy and Governor General.[citation needed] The Afghan side was represented by Sahibzada Abdul Latif and a former governor of Khost province in Afghanistan, Sardar Shireendil Khan, representing Amir Abdur Rahman Khan.[citation needed] The original 1893 Durand Line Agreement was written in English, with translated copies in Dari.

The resulting agreement or treaty led to the creation of a new province called at the time North-West Frontier Province now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a province of Pakistan which includes FATA and Frontier Regions.

It also included the areas of Multan, Mianwali, the Bahawalpur, and Dera Ghazi Khan. These areas were part of the Durrani Empire from 1709 until the 1820s when the Sikh Empire, followed by the British, invaded and took possession.[20]

Demarcation surveys on the Durand Line

Afghanistan before the 1893 Durand Line Agreement

The initial and primary demarcation, a joint Afghan-British survey and mapping effort, covered 800 miles and took place from 1894 to 1896. "The total length of the boundary which had been delimitated and demarcated between March 1894 and May 1896, amounted to 800 miles." Detailed topographic maps locating hundreds of boundary demarcation pillars were soon published and are available in the Survey of India collection at the British Library.[21]

The complete 20-page text of these detailed joint Afghan-British demarcation surveys is available in several sources, which point out that "J. Donald and Sardar Shireendil Khan settled the boundary from Sikaram Peak (34-03 north, 69-57 east) to Laram Peak (33-13 north, 70-05 east) in a document dated 21 November 1894. This section was marked by 76 pillars. The boundary from Laram Peak to ... Khwaja Khidr (32–34 north) ... was surveyed and marked by H. A. Anderson in concert with various Afghan chiefs ... marked by (39) pillars which are described in a report dated 15 April 1895. L. W. King (issued a report dated) 8 March 1895 (on) the demarcation of the section from Khwaja Khidr to Domandi (31–55 north) by 31 pillars. The line from Domandi to New Chaman (30–55 north, 66-22 east) was marked by 92 pillars by a joint demarcation commission led by Captain (later Lt. Colonel Sir) Henry McMahon and Sardar Gul Muhammad Khan (who issued a) report dated 26 February 1895. McMahon also led the demarcation commission with Muhammad Umar Khan which marked the boundary from new Chaman to ... the tri-junction with Iran ... by 94 pillars which are described in a report dated 13 May 1896."[22][23]

In 1896, the long stretch from the Kabul River to China, including the Wakhan Corridor, was declared demarcated by virtue of its continuous, distinct watershed ridgeline, leaving only the section near the Khyber Pass, which was finally demarcated in the treaty of 22 November 1921 signed by Mahmud Tarzi, "Chief of the Afghan Government for the conclusion of the treaty" and "Henry R. C. Dobbs, Envoy Extraordinary and Chief of the British Mission to Kabul."[22]

A very short adjustment to the demarcation was made at Arundu (Arnawai) in 1933–34.[3][22]

Cultural impact of the Durand Line

Shortly after demarcation of the Durand Line, the British began connecting the region on its side of the Durand Line to the vast and expansive Indian railway network. Meanwhile, Abdur Rahman Khan conquered the Nuristanis and made them Muslims. Concurrently, Afridi tribesmen began rising up in arms against the British, creating a zone of instability between Peshawar and the Durand Line. Further, frequent skirmishes and wars between the Afghan state and the British Raj starting in the 1870s made travel between Peshawar and Jalalabad almost impossible. As a result, travel across the boundary was almost entirely halted. Further, the British recruited tens of thousands of local Pashtuns into the British Indian Army and stationed them throughout British India and southeast Asia. Exposure to India, combined with the ease of travel eastwards into Punjab and the difficulty of travel towards Afghanistan, led many Pashtuns to orient themselves towards the heartlands of British India and away from Kabul. By the time of Indian independence, political opinion was divided into those who supported a homeland for Muslim Indians in the shape of Pakistan, those who supported reunification with Afghanistan, and those who believed that a united India would be a better option.

British Indian Empire declares war on Afghanistan

The Durand Line triggered a long-running controversy between the governments of Afghanistan and the British Indian Empire,[1] especially after the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Afghan War when Afghanistan's capital (Kabul) and its eastern city of Jalalabad were bombed by the No. 31 and No. 114 Squadrons of the British Royal Air Force in May 1919.[24][25] Afghan rulers reaffirmed in the 1919, 1921, and 1930 treaties to accept the Indo-Afghan frontier.[26][22][27]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The Afghan Government accepts the Indo–Afghan frontier accepted by the late Amir

— Article V of the August 8, 1919 Treaty of Rawalpindi

The two high contracting parties mutually accept the Indo-Afghan frontier as accepted by the Afghan Government under Article V of the Treaty concluded on August 8, 1919

— Article II of the November 22, 1921 finalising of the Treaty of Rawalpindi

Territorial dispute between Afghanistan and Pakistan

Pakistan inherited the 1893 agreement and the subsequent 1919 Treaty of Rawalpindi after the partition from the British India in 1947. There has never been a formal agreement or ratification between Islamabad and Kabul.[28] Pakistan believes, and international convention under uti possidetis juris supports, the position that it should not require an agreement to set the boundary;[26] courts in several countries around the world and the Vienna Convention have universally upheld via uti possidetis juris that binding bilateral agreements are "passed down" to successor states.[29] Thus, a unilateral declaration by one party has no effect; boundary changes must be made bilaterally.[30]

At the time of independence, the indigenous Pashtun people[15] living on the border with Afghanistan were given only the choice of becoming a part either of India or Pakistan.[5] Further, by the time of the Indian independence movement, prominent Pashtun nationalists such as Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his Khudai Khidmatgar movement advocated a united India, and not a united Afghanistan – highlighting the extent to which infrastructure and instability together began to erode Pashtun self-identification with Afghanistan.[31] By the time of independence, popular opinion amongst Pashtuns was split amongst the majority who wished to join the newly formed state of Pakistan, and the minority who wished to become a part of the Dominion of India. When the idea of a united India failed, Ghaffar Khan pledged allegiance to Pakistan and started campaigning for the autonomy of Pakistan's Pashtuns.[31]

Some scholars have suggested that memoranda from British officials in the 1890s suggest that the Durand Line was never intended to be a boundary demarcating sovereignty, but rather a line of control beyond which either side agreed not to interfere unless there were an expedient need to do so. These same scholars suggest that the frontier agreement was not of the form of an "executed clause", which usually caters for sovereign boundary demarcation and which cannot be unilaterally repudiated.[citation needed] And yet, within four years, joint Afghan-British demarcation teams had completed detailed demarcation surveys and demarcation text for most of the Durand Line (see above), contrary to the conjecture that the 1893 agreement was of the form of an "executory clause", similar to those pertaining to trade agreements, which are ongoing and can be repudiated by either party at any time. Other legal questions currently being considered are those of state practice, i.e. whether the relevant states de facto treat the frontier as an international boundary, and whether the de jure independence of the Tribal Territories at the moment of Indian Independence undermine the validity of Durand Agreement and subsequent treaties.[32][33]

On July 26, 1949, when Afghan–Pakistan relations were rapidly deteriorating, a loya jirga was held in Afghanistan after a military aircraft from the Pakistan Air Force bombed a village on the Afghan side of the Durand Line. In response, the Afghan government declared that it recognised "neither the imaginary Durand nor any similar line" and that all previous Durand Line agreements were void.[34] They also announced that the Durand ethnic division line had been imposed on them under coercion/duress and was a diktat. This had no tangible effect as there has never been a move in the United Nations to enforce such a declaration due to both nations being constantly busy in wars with their other neighbors (See Indo-Pakistani wars and Civil war in Afghanistan). In 1950 the House of Commons of the United Kingdom held its view on the Afghan-Pakistan dispute over the Durand Line by stating:

His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom has seen with regret the disagreements between the Governments of Pakistan and Afghanistan about the status of the territories on the North West Frontier. It is His Majesty's Government's view that Pakistan is in international law the inheritor of the rights and duties of the old Government of India and of his Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom in these territories and that the Durand Line is the international frontier.[35]

— Philip Noel-Baker, June 30, 1950

At the 1956 SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) Ministerial Council Meeting held at Karachi, capital of Pakistan at the time, it was stated:

The members of the Council declared that their governments recognised that the sovereignty of Pakistan extends up to the Durand Line, the international boundary between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and it was consequently affirmed that the Treaty area referred to in Articles IV and VIII of the Treaty includes the area up to that Line.[36]

— SEATO, March 8, 1956

Contemporary era

Afghan mujahideen representatives with President Ronald Reagan at the White House in 1983.

Pakistan's intelligence agency the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been heavily involved in the affairs of Afghanistan since the late 1970s. During Operation Cyclone, the ISI with support and funding from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the United States recruited mujahideen militant groups on the Pakistani side of the Durand line to cross into Afghanistan's territory for missions to topple the Soviet-backed Afghan government.[37] Afghanistan KHAD was one of two secret service agencies believed to have been conducting bombings in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (NWFP) during the early 1980s.[38] U.S State Department blamed WAD (a KGB created Afghan secret intelligence agency) for terrorist bombings in Pakistan's cities in 1987 and 1988.[39][40] It is also believed that Afghanistan's PDPA government supported leftist Al-Zulfiqar organisation of Pakistan, the group accused of the 1981 hijacking of a Pakistan International Airlines plane from Karachi to Kabul.

CIA-funded and ISI-trained mujahideen fighters crossing the Durand Line to fight the Soviet-backed Afghan government in 1985.

After the collapse of the pro-Soviet Afghan government in 1992, Pakistan, despite Article 2 of the Durand Line Agreement which states "The Government of Pakistan will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan," attempted to create a puppet state in Afghanistan prior to Taliban control according to US Special Envoy on Afghanistan Peter Tomsen.[41] According to a summer 2001 report in The Friday Times, even the Taliban leaders challenged the very existence of the Durand Line when former Afghan Interior Minister Abdur Razzaq and a delegation of about 95 Taliban visited Pakistan.[42] The Taliban refused to endorse the Durand Line despite pressure from Islamabad, arguing that there shall be no borders among Muslims. When the Taliban government was removed in late 2001, the Afghan President Hamid Karzai also began resisting the Durand Line,[43] and today the present Government of Afghanistan does not recognize Durand Line as its international border. No Afghan government has recognized the Durand Line as its border since 1947.[44][45]

A line of hatred that raised a wall between the two brothers.

— Hamid Karzai

The Afghan Geodesy and Cartography Head Office (AGCHO) depicts the line on their maps as a de facto border, including naming the "Durand Line 2310 km (1893)" as an "International Boundary Line" on their home page.[46] However, a map in an article from the "General Secretary of The Government of Balochistan in Exile" extends the border of Afghanistan to the Indus River.[26] The Pashtun dominated Government of Afghanistan not only refuses to recognise the Durand Line as the international border between the two countries, it claims that the Pashtun territories of Pakistan rightly belong to Afghanistan.[10] Many in Afghanistan as well as some Pakistani politicians find the existence of the international boundary splitting ethnic Pashtun areas to be at least objectionable if not abhorrent.[47] Some argue that the 1893 treaty expired in 1993, after 100 years elapsed, and should be treated similarly to the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory.[26][48][49][42][50] However, neither the relatively short Durand Line Agreement itself nor the much longer joint boundary demarcation documents that followed in 1894-6 make any mention of a time limit suggesting the treaty should be treated similar to the Curzon Line and Mexican Cession or any other international boundary agreement (none of which have time limits.) In 2004, spokespersons of U.S. State Department's Office of the Geographer and Global Issues and British Foreign and Commonwealth Office also pointed out that the Durand Line Agreement has no mention of an expiration date.

Recurrent claims that (the) Durand Treaty expired in 1993 are unfounded. Cartographic depictions of boundary conflict with each other, but Treaty depictions are clear.[28]

— A spokesperson for U.S. State Department's Office of the Geographer and Global Issues

Because the Durand Line divides the Pashtun and Baloch people, it continues to be a source of tension between the governments of Pakistan and Afghanistan.[51] In August 2007, Pakistani politician and the leader of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, Fazal-ur-Rehman, urged Afghanistan to recognise the Durand Line.[52] Press statements from 2005 to 2007 by former Pakistani President Musharraf calling for the building of a fence on the Durand Line have been met with resistance from numerous Pashtun political parties within Afghanistan.[53][54][55] Pashtun politicians in Afghanistan strenuously object to even the existence of the Durand Line border.[47]

Aimal Faizi, spokesman for the Afghan President, stated in October 2012 that the Durand Line is "an issue of historical importance for Afghanistan. The Afghan people, not the government, can take a final decision on it."[9]

Recent border conflicts

An MQ-9 Reaper unmanned aerial vehicle, one of a unit which is launched from Afghanistan to engage targets on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line.

In July 2003, Pakistani and Afghan forces clashed over border posts. The Afghan government claimed that Pakistani military established bases up to 600 meters inside Afghanistan in the Yaqubi area near bordering Mohmand Agency.[56] The Yaqubi and Yaqubi Kandao (Pass) area were later found to fall within Afghanistan.[57] In 2007, Pakistan erected fences and posts a few hundred meters inside Afghanistan, near the border-straddling bazaar of Angoor Ada in South Waziristan, but the Afghan National Army quickly removed them and began shelling Pakistani positions.[56] Leaders in Pakistan said the fencing was a way to prevent Taliban militants from crossing over between the two nations but Afghan President Hamid Karzai believed that it is Islamabad's plan to permanently separate the Pashtun tribes.[58]Special Forces from the United States Army have been based at Shkin, Afghanistan, seven kilometers west of Angoor Ada, since 2002.[59] In 2009, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and American CIA have begun using unmanned aerial vehicles from the Afghan side to hit terrorist targets on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line.[60]

Afghan customs officials check travelers' passports at Torkham Gate in Nangarhar province.

The border area between Afghanistan and Pakistan has long been one of the most dangerous places in the world, due largely to very little government control. It is legal and common in the region to carry guns, and assault rifles and explosives are common.[61] Many forms of illegal activities take place, such as smuggling of weapons, narcotics, lumber, copper, gemstones, marble, vehicles, and electronic products, as well as ordinary consumer goods.[51][62][63][64][65] Kidnappings and murders are frequent.[7] Numerous outsiders with extremist views came from around the Muslim world to settle in the Durand Line region over the past 30 years. While most of the time the Taliban cross the Durand Line from Pakistan into Afghanistan and carry out attacks inside Afghan cities, sometimes they cross from the Afghanistan side of the border and attack Pakistani security forces and cities. Recently, 300 Taliban militants from Afghanistan's territory launched attacks on Pakistani border posts in which 34 Pakistani security forces were believed to be killed. It is also believed Swat District Taliban leader Maulana Fazlullah is hiding somewhere inside Afghanistan.[66] In June 2011 more than 500 Taliban militants entered Upper Dir area from Afghanistan and killed more than 30 Pakistani security forces. Police said the attackers targeted a checkpost, destroyed two schools and several houses, while killing a number of civilians.[67]

The governments of Pakistan and Afghanistan are both trying to extend the rule of law into the border areas. At the same time, the United States is reviewing the Reconstruction Opportunity Zones (ROZ) Act in Washington, D.C., which is supposed to help the economic status of the Pashtun and Baloch tribes by providing jobs to a large number of the population on both sides of the Durand Line border.[68]

Much of the northern and central Durand line is quite mountainous, where crossing the border is often only practical in the numerous passes through the mountains. Border crossings are very common, especially among Pashtuns who cross the border to meet relatives or to work. The movement of people crossing the border has largely been unchecked or uncontrolled,[51] although passports and visas are at times checked at official crossings. In June 2011 the United States installed a biometric system at the border crossing near Spin Boldak aimed at improving the security situation and blocking the infiltration of insurgents into southern Afghanistan.[69]

Between June and July 2011, Pakistan Chitral Scouts and local defence militias suffered deadly cross border raids. In response the Pakistani military reportedly shelled some Afghan villages in Afghanistan's Nuristan, Kunar, Nangarhar, and Khost provinces resulting in a number of Afghan civilians being killed.[70] Afghan sources claimed that nearly 800 rounds of missiles were fired from Pakistan, hitting civilian targets inside Afghanistan.[71] The reports claimed that attacks by Pakistan resulted in the deaths of 42 Afghan civilians, including children, wounded many others and destroyed 120 homes. Although Pakistan claims it was an accident and just routine anti Taliban operations, some analysts believe that it could have been a show of strength by Islamabad. For example, a senior official at the Council on Foreign Relations explained that because the shelling was of large scale it is more likely to be a warning from Pakistan than an accident.[72]

I'm speculating, but natural possibilities include a signal to Karzai and to (the United States) that we can't push Pakistan too hard.[72]

— Stephen Biddle

The United States and other NATO states often ignore this sensitive issue, likely because of potential effects on their war strategy in Afghanistan. Their involvement could strain relations and jeopardise their own national interests in the area.[10] This came after the November 2011 NATO bombing in which 24 Pakistani soldiers were killed.[73] In response to that incident, Pakistan decided to cut off all NATO supply lines as well as boost border security by installing anti-aircraft guns and radars to monitor air activity.[74] Regarding the Durand Line, some rival maps are said to display discrepancies of as much as five kilometers.[75]

Trench being built alongside the border

In June 2016, Pakistan announced that it had completed 1,100 km of trenches along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border (Durand Line) in Balochistan to check movement of terrorists and smugglers across border into Pakistan from Afghanistan.[76] Plans to expand this trench/ berm/ fence work were announced in March 2017.[77] Plans are to build 338 check posts and forts along the border by 2019.[78]

2017 border closures

On 16 February, Pakistan closed the border crossings at Torkham and Chaman due to security reasons following the Sehwan blast.[79][80] On 7 March, the border was reopened for two days to facilitate the return of people to their respective countries who had earlier crossed the border on valid visas. The decision was taken after repeated requests by Afghanistan’s government to avert ‘a humanitarian crisis’.[81][82] According to a Pakistani official, 24,000 Afghans returned to Afghanistan, while 700 Pakistanis returned to Pakistan, before the border was indefinitely closed again.[83] On 20 March, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif ordered the reopening of Afghanistan–Pakistan border as a "goodwill gesture", 32 days after it was closed.[84][85]

On 5 May, following an attack on Pakistani census team by Afghan forces and the resulting exchange of fire between the two sides, the border was closed again.[86] On 27 May, Pakistan reopened the border after a request from Afghan authorities, marking the end of the border closure that lasted 22 days.[87]

India-Afghanistan border crossings

See also

- Af-Pak

- Pakistan–Afghanistan barrier

- Afghanistan-Pakistan relations

- Afghanistan–Pakistan skirmishes

- Sykes-Picot Agreement

- Scramble for Africa

References

^ abc Smith, Cynthia (August 2004). "A Selection of Historical Maps of Afghanistan – The Durand Line". United States: Library of Congress. Retrieved 2011-02-11..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "The total length of the boundary which had been delimited and demarcated between March 1894 and May 1896, amounted to 800 miles." The long stretch from the Kabul River to China, including the Wakhan Corridor, was declared demarcated by virtue of its continuous, distinct watershed ridgeline, leaving only the section near the Khyber Pass, which was finally demarcated in 1921: Brig.-Gen. Sir Percy Sykes, K.C.I.E., C.B., C.M.G., Gold Medalist of the Royal Geographical Society (1940). "A History of Afghanistan Vol. II". London: MacMillan & Co. pp. 182–188, 200–208. Retrieved 2009-12-05.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ ab An adjustment to the demarcation was made at Arundu in the early 1930s: Hay, Maj. W. R. (October 1933). "Demarcation of the Indo-Afghan Boundary in the Vicinity of Arandu". Geographical Journal. LXXXII (4).

^ Uradnik, Kathleen (2011). Battleground: Government and Politics, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 18. ISBN 9780313343131.

^ ab "No Man's Land". Newsweek. United States. February 1, 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2011-02-11.Where the imperialists' Great Game once unfolded, tribal allegiances have made for a "soft border" between Afghanistan and Pakistan—and a safe haven for smugglers, militants and terrorists

^ Bajoria, Jayshree (March 20, 2009). "The Troubled Afghan-Pakistani Border". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

^ ab "Japanese nationals not killed in Pakistan: FO". Dawn News. Pakistan. September 7, 2005. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ Walker, Philip (24 June 2011). "The World's Most Dangerous Borders: Afghanistan and Pakistan". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

^ ab "No change in stance on Durand Line: Faizi". Pajhwok Afghan News. October 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-11.But Afghanistan has never accepted the legitimacy of this border, arguing that it was intended to demarcate spheres of influence rather than international frontiers.

^ abc Grare, Frédéric (October 2006). "Carnegie Papers – Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations in the Post-9/11 Era" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ Rahi, Arwin. "Why the Durand Line Matters". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

^ Micallef, Joseph V. (2015-11-21). "Afghanistan and Pakistan: The Poisoned Legacy of the Durand Line". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

^ Rubin, Barnett R. (2013-03-15). Afghanistan from the Cold War through the War on Terror. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199970414.

^ Siddiqui, Naveed (5 March 2017). "Afghanistan will never recognise the Durand Line: Hamid Karzai". Dawn. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

^ ab "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies. August 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ "The History of Herodotus, Chapter 7". George Rawlinson. piney.com. 440 BC. Retrieved 2011-02-11. Check date values in:|date=(help)

^ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (Firishta). "History of the Mohamedan Power in India". Persian Literature in Translation. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

^ "Baloch". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Version. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Afghanistan (Southern Khorasan / Arachosia)". The History Files. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

^ Multan city History Archived 2010-03-24 at the Wayback Machine.

^ BRIG.-GEN. SIR Percy Sykes, K.C.I.E., C.B., C.M.G., GOLD MEDALIST OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY. "A HISTORY OF AFGHANISTAN VOL. II". MACMILLAN & CO. LTD, 1940, LONDON. pp. 182–188, 200–208. Retrieved 2009-12-05.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ abcd Prescott, J. R. V. Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty. Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, Australia, 1975. pp. 182–208. ISBN 0-522-84083-3.

^ Muhammad Qaiser Janjua. "In the Shadow of the Durand Line; Security, Stability, and the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan" (PDF). Naval Postgraduate School, Monterrey, California, US, 2009. pp. 22–27, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

^ "The Road to Kabul: British armies in Afghanistan, 1839–1919". National Army Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-11-26. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ "Afghanistan 1919–1928: Sources in the India Office Records". British Library. Retrieved 2011-02-11.1919 (May), outbreak of Third Anglo-Afghan War. British bomb Kabul and Jalalabad;

^ abcd End of Imaginary Durrand Line: North Pakistan belongs to Afghanistan by Wahid Momand

^ Jeffery J. Roberts, The Origins of Conflict in Afghanistan (Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2003), page 121.

^ ab Hasan, Khalid (February 1, 2004). "'Durand Line Treaty has not lapsed'". Daily Times. Pakistan. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ Over 90% of present African nations signed both the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) charter and the 1964 Cairo Declaration, both of which "proclaimed the acceptance of colonial borders as the borders between independent states...through the legal principle of uti possidetis." Hensel, Paul R. "Territorial Integrity Treaties and Armed Conflict over Territory" (PDF). Department of Political Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, US. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

^ Hensel, Paul R.; Michael E. Allison and Ahmed Khanani (2006) "Territorial Integrity Treaties, Uti Possidetis, and Armed Conflict over Territory." Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. Presented at the Shambaugh Conference "Building Synergies: Institutions and Cooperation in World Politics," University of Iowa, 13 October 2006.

^ ab Rahi, Arwin (22 August 2017). "Would India and Afghanistan have had a close relationship had Pakistan not been founded?". Dawn. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

^ "The Durand Line: History and Problems of the Afghan-Pakistan Border" Bijan Omrani, published in Asian Affairs, vol. 40, Issue 2, 2009, p.177-195.

^ "Rethinking the Durand Line: The Legality of the Afghan-Pakistani Frontier", Bijan Omrani and Frank Ledwidge, RUSI Journal, Oct 2009, Vol. 154, No. 5,

^ Baxter, Craig (1997). "The Pashtunistan Issue". United States: Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ Durand Line, 1956, page 12.

^ Durand Line, 1956, page 13

^ "So called "terrorist camps" (in 1989?) and training". Support Daniel Boyd's Blog.

^ "Pakistan Knocking at the Nuclear Door". Time. March 30, 1987. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

^ Kaplan, Robert D. (August 23, 1989). "How Zia's Death Helped the U.S". The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

^ Pear, Robert (June 25, 1989). "F.B.I. Allowed to Investigate Crash That Killed Zia". The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

^ "Interview with Peter Tomsen,". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 2011-02-11.President George H. W. Bush's special envoy and ambassador to the Afghan resistance from 1989 to 1992

^ ab The Unholy Durand Line, Buffering the Buffer Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. by Dr. G. Rauf Roashan. August 11, 2001.

^ "Pakistan's Ethnic Fault Line" by Selig S. Harrison, The Washington Post. May 11, 2009.

^ Natural Resources in Afghanistan: Geographic and Geologic Perspectives on Centuries of Conflict By John F. Shroder. Elselvier, San Diego, California, USA. 2014. p290

^ admin interview with former President Hamid Karzai (2 September 2016). We will respect Pashtuns’ decision on Pashtunistan: Karzai. Afghan Times.“No one will recognize it. It cannot separate the nation. The line has not separated the nation."

^ "Afghan Geodesy and Cartography Head Office (AGCHO)". Archived from the original on 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

^ ab PAN, Durand Line not a legitimate border: Zoori, August 3, 2009.

^ Government & Politics: Overview Of Current Political Situation In Afghanistan"(3) The Durand Line is an unofficial porous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 1893, the British and the Afghan Amir (Abdur Rahman Khan) agreed to set up the Durand line (named after the foreign Secretary of the Indian government, Sir Mortimer Durand) to divide Afghanistan and what was then British India.

^ Durand Line

^ Daily Times – Durand Line Agreement: 1893 pact had no expiry limit: expert, by Mohammed Rizwan. September 30, 2005.

^ abc Newsweek, No Man's Land – Neighbor's Interference

^ Dawn News, Fazl urges Afghanistan to recognise Durand Line

^ PAN, Pashtuns on both sides of Pak-Afghan border show opposition to fencing plan, January 3, 2007.

^ PAN, More protests against fencing, January 10, 2007.

^ PAN, Fencing plan may defame Pakistan: Fazl, January 10, 2007.

^ ab John Pike. "RFE/RL Afghanistan Report". globalsecurity.org.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2007-04-03.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) NGA Geonames database

^ Clash erupts between Afghan, Pakistani forces over border fence – South Asia Archived 2013-01-23 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Fire Base Shkin / Fire Base Checo. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

^ NK. "NEWKERALA.COM for News, Information & Entertainment Stuff". newkerala.com.

^ Khan, Kamran. "Pakistan's Tribal Areas". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

^ Amber Robinson (9 June 2009). "Soldiers disrupt timber smuggling in Afghan province". Retrieved 14 February 2013.

^ Abdul Sami Paracha (28 June 2002). "Timber smuggling from Afghanistan on the rise". Dawn. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

^ "Six Pakistanis held in Afghanistan on timber smuggling charge". Dawn. 19 September 2005. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

^ "Pakistan suggests curbs to end smuggling from Afghanistan". 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

^ The News.pk, 36 soldiers die in cross-border Chitral attack, August 28, 2011.

^ The Frontier Post, Pakistan, Peshawar Archived 2012-04-21 at the Wayback Machine.. Thefrontierpost.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

^ "S.496: Afghanistan and Pakistan Reconstruction Opportunity Zones Act of 2009 – U.S. Congress – OpenCongress". OpenCongress. Archived from the original on 2009-07-18.

^ Biometric system installed in Spin Boldak. June 9, 2011.

^ "Pakistan fires missiles into Khost, say border police". Pajhwok Afghan News. 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2011-07-06.Nearly a dozen missiles were fired from Pakistan into Afghanistan's southeastern Khost province over the past 24 hours, border police said on Friday.

^ "Afghanistan won't fire back on Pakistan: Karzai". Reuters. 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

^ ab Nichols, Michelle (July 7, 2011). "Afghanistan, Pakistan to coordinate amid cross-border confusion". United States: Reuters. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

^ Tolo News, "Terrorist Safe Havens in Pakistan Must Go, Joint Chiefs Head Says" Archived 2012-01-17 at the Wayback Machine.. 10 December 2011.

^ the CNN Wire Staff (10 December 2011). "Pakistan boosts border security after airstrike". CNN.

^ Boone, Jon (November 27, 2011). "Nato air attack on Pakistani troops was self-defence, says senior western official". The Observer. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

^ Butt, Qaiser (20 June 2016). "1,100km trench built alongside Pak-Afghan border in Balochistan". Express Tribune. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

^ Gul, Ayaz (25 March 2017). "Pakistan Begins Fencing of Afghan Border". Voice of America. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

^ https://www.dawn.com/news/1327567/former-ttp-spokesman-ehsanullah-ehsan-has-turned-himself-in-pak-army

^ "Pak. closes Afghan border crossing". The Hindu. Associated Press. February 19, 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ "Pak-Afghan border closed for indefinite period: ISPR". The News International. February 16, 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ Mashal, Mujib (March 5, 2017). "Closed Afghan-Pakistani Border Is Becoming 'Humanitarian Crisis'". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ "People throng Torkham as border reopens for two days". Express Tribune. March 7, 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ "Pakistan indefinitely closes Afghan border". Sky News. Reuters. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ "Pakistani prime minister orders the reopening of border with Afghanistan, ending costly closure". LA Times. Associated Press. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ Afzaal, Ali (March 21, 2017). "Pak-Afghan border reopens after 32 days". Geo News. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

^ "Pakistan-Afghanistan crossing closed after border clash". Al Jazeera English. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

^ Siddiqui, Naveed (28 May 2017). "Pakistan opens Chaman border crossing on 'humanitarian grounds' after 22 days". Dawn. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

Further reading

- "Durand’s Curse: A Line Across the Pathan Heart" by Rajiv Dogra, Publisher: Rupa Publications India

"Special Issue: The Durand Line". Internationales Asienforum. 44 (1–2). May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Durand line. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Durand Line Agreement |

- Text of the Durand Line Agreement, November 12, 1893

- The Durand Line Agreement (1893): Its Pros and Cons

"The Durand Line: History and Problems of the Afghan-Pakistan Border" Bijan Omrani, published in Asian Affairs, vol. 40, Issue 2, 2009.

"Rethinking the Durand Line: The Legality of the Afghan-Pakistan Border", published in the RUSI Journal, Oct 2009, Vol. 154, No. 5- No Man's Land – Where the imperialists' Great Game once unfolded, tribal allegiances have made for a "soft border" between Afghanistan and Pakistan—and a safe haven for smugglers, militants and terrorists

- Fly-over of part of the Durand Line

- The Durand Line

Culture, Politics Hinder U.S. Effort to Bolster Pakistani Border, The Washington Post March 30, 2008

"Border Complicates War in Afghanistan", The Washington Post, April 4, 2008