Charles N. Haskell

| Charles Nathaniel Haskell | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Governor of Oklahoma | |

In office November 16, 1907 – January 9, 1911 | |

| Lieutenant | George W. Bellamy |

| Preceded by | Frank Frantz as Territorial Governor |

| Succeeded by | Lee Cruce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1860-03-13)March 13, 1860 Leipsic, Ohio |

| Died | July 5, 1933(1933-07-05) (aged 73) Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

| Resting place | Muskogee, Oklahoma |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Lucie Pomeroy Haskell Lillian Gallup Haskell |

| Profession | teacher, lawyer |

Charles Nathaniel Haskell (March 13, 1860 – July 5, 1933) was an American lawyer, oilman, and politician who was the first governor of Oklahoma. As a delegate to Oklahoma's constitutional convention in 1906, he played a crucial role in drafting the Oklahoma Constitution and gaining Oklahoma's admission into the United States as the 46th state in 1907. A prominent businessman in Muskogee, he helped the city grow in importance. He represented the city as a delegate in both the Oklahoma convention and an earlier convention that was a failed attempt to create a U.S. state of Sequoyah.

During Oklahoma's constitutional convention, Haskell succeeded in pushing for the inclusion of prohibition and blocking the inclusion of women's suffrage in the Oklahoma Constitution. As governor, he was responsible for moving the state capital to Oklahoma City, establishing schools and state agencies, reforming the territorial prison system, and enforcing prohibition.

Lee Cruce succeeded Haskell, who died of a stroke in 1933.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Private career

3 Marriage and family

4 Move to Muskogee

5 Gubernatorial campaign

6 Governor of Oklahoma

7 National politics

8 Later life, death and legacy

9 State of the State Speeches

10 Sources

11 References

12 External links

Early life and education

Born in West Leipsic, Ohio on March 13, 1860, Charles Haskell was the son of George R. Haskell, a cooper who died when the boy was three years old. His mother, Jane H. Reeves Haskell, worked for the local Methodist church as a bell ringer and custodian to support the six children.[1] At the age of 10, he started working as a farm boy for a farmer named Miller in Putnam County, Ohio, where he lived and worked for eight years as he grew into adulthood. Miller was a school teacher, but as the young Haskell had to work, he did not have time to attend school. Instead, Miller's wife taught him at home and Haskell earned a teaching certificate at age 17.

Private career

Haskell became a teacher at age 18 and taught for three years in Putnam County. On December 6, 1880, he passed the bar exam, and became a practicing attorney at age 20 despite having no academic training in the field. In his work as an attorney, Haskell became one of the most successful lawyers in Ottawa, Ohio, the county seat, as well as one of the most prominent members of the Democratic Party in northwestern Ohio. In 1888, Haskell started work as a general contractor; for the next 16 years, his business career gave him an understanding of American industrialism. During this time, he lived in New York City and in San Antonio, Texas.[1]

Marriage and family

Haskell married Lucie Pomeroy, daughter of a prominent Ottawa family, on October 11, 1881. Their children were Norman, who became a Muskogee lawyer; Murray, a bank cashier; and Lucie. Mrs. Haskell died in March 1888.[1]

Haskell remarried in 1889, to Lillie Elizabeth Gallup. They had three children: Frances, Joe and Jane.[1]

Move to Muskogee

Haskell moved to Muskogee, Oklahoma, where he would become a prominent resident.

With the Land Run of 1889 and the passage of the Organic Act in 1890, Oklahoma Territory was gaining importance on the national scene. Haskell moved his family to Muskogee, the capital of the Creek Nation, in March 1901. When he arrived, Haskell found Muskogee a dry, sleepy village of some 4,500 people. Upon his arrival a movement of building business blocks began and he built the first five-story business block in Oklahoma Territory.

Haskell organized and built most of the railroads running into Muskogee. He is said to have built and owned 14 brick buildings in the city. Through his influence, Muskogee grew to be a center of business and industry with a population of more than 20,000 inhabitants.[1] Haskell often told others that he hoped Muskogee would become the “Queen City of the Southwest.”

His success earned him clout in the politics of Indian Territory and the attention of the Creek Nation. During this time, the Native American nations in Indian Territory were talking of creating a state and joining the Union under the name of the State of Sequoyah. The Creeks selected Haskell as their official representative to the conventions, in the position of vice-president for the Five Civilized Tribes, held in Eufaula, Oklahoma in 1902 and Muskogee in 1905. Of the six delegates at the Muskogee convention, all were of Native American descent, save two: Haskell and William H. Murray. Even though U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt blocked the attempt to create Sequoyah, Haskell wrote a large portion of the proposed state’s constitution. Though Haskell publicly worked for a separate state for Indian Territory, privately, he was thrilled to see the Sequoyah proposal defeated. Haskell believed it would force the Indian leaders to join in statehood with Oklahoma Territory.

The United States Congress and President Roosevelt agreed that Oklahoma and Indian Territories could only enter the Union as one state, the State of Oklahoma. After the federal passage of the Enabling Act in 1906, Haskell was elected as a delegate by the largest margin in the new state, representing the seventy-sixth district, which included Muskogee. Traveling to Guthrie and the Oklahoma Constitutional convention on November 20, 1906, Haskell would meet William H. Murray from the Muskogee convention and Robert L. Williams. Because of their meetings at both conventions, Haskell would gain a friendship with Murray that would last until the end of his life.

The delegates to the Guthrie convention included many of those who had served in the Sequoyah convention in Muskogee, and a number of the ideas proposed for the new constitution were based upon the rejected Sequoyah constitution. Haskell owned the New State Tribune, and through its editorial columns advocated for the propositions he wanted in the new constitution, most of which were incorporated into the document, in substance if not in form. While Murray served as the convention's president, delegates recognized Haskell's power in the body. A local newspaper during the time, the Guthrie Report, called Haskell “the power behind the throne.”

Haskell had a perfect attendance and voting record during the session. He advocated for provisions that affected both territories’ labor problems and avocation for representatives of organized labor. Haskell also drafted a report drawing up county boundaries, led the crusade for state prohibition, introduced Jim Crow laws and successfully kept female suffrage out of the state constitution.

Gubernatorial campaign

William Jennings Bryan supported Haskell in his 1907 campaign.

At Tulsa on March 26, 1907, during the recess before the final adoption of the constitution by the convention, Haskell held a large Democratic Party banquet at the Brady Hotel, attended by between 500 and 600 of the leading Democrats of the new state. During this banquet, the first campaigns for governor were formally inaugurated. It was during the course of that evening that Haskell was presented by his friends with the honors of the Democratic gubernatorial candidacy. Among the other potential candidates were Thomas Doyle of Perry and Lee Cruce of Ardmore. Haskell, like other prominent Democrats at the time, had the strong support of labor and agriculture leaders.[2]

Unfortunately for Haskell, the primaries for governor were set for June 8, and Doyle and Cruce had already been campaigning; Haskell had little time. During his campaign, Haskell made 88 speeches in 45 days, and reached nearly every county, while the lieutenants of the respective candidates were vigorously working in the school districts and securing support in every community. Haskell’s hard working nature led him to win the Democratic nomination. Haskell's victory in the primaries was carried by a more than 4,000-vote majority. He immediately confronted a new opponent in the opposite party, the Republican territorial governor, Frank Frantz, who was nominated by the Republican caucus at Tulsa.

Frantz, the current territorial governor, a former Rough Rider, a friend of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, and with the federal prestige and support backing him, was the strongest candidate the Republican party could have presented to face Haskell. Haskell challenged his opponent to joint public discussions throughout the state, and every problem concerned with the administration of the new state came up in debate during the campaign.

During the course of the campaign, two nationally prominent figures spoke at various locations: Republican presidential nominee William Howard Taft and Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan. Unfortunately for the Republicans, Taft’s disapproval of Oklahoma’s proposed constitution and his advice that the people vote against it caused the voters to react in favor of the Democrats. Haskell won the gubernatorial race by more than 30,000 votes on September 17, 1907.[1] On the same day, the voters ratified the Oklahoma Constitution.

After Haskell's election and the approval of the constitution, a Republican approached the governor-elect and is reported to have said, "You have so written the constitution and carried on this fight in a way that the Republicans can't get anything in the state for fifty years." Haskell's eyes had a twinkle in them when he replied, "Well, that's soon enough, isn't it?"

Governor of Oklahoma

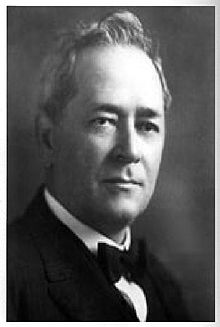

Governor Haskell as he appeared upon entering office.

On November 16, 1907, five minutes after it was known that Oklahoma had officially become a state, Guthrie Leader editor Leslie G. Niblack administered the oath of office to Haskell. The ceremony took place privately in Haskell's hotel apartments in the presence of his immediate family, Robert Latham Owen, United States Senator-elect, and Thomas Owen of Muskogee, Haskell's former political manager. Haskell’s inaugural address at Guthrie, delivered on the south steps of the Carnegie Library, quickly lifted him into national prominence.

Haskell’s old friends William H. Murray and Robert L. Williams also came into power with the state’s founding; with Murray as the state’s first Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives and Williams appointed, by Haskell, as the first Oklahoma Supreme Court chief justice. Haskell set the precedents for the use of executive power.

During the 1st Oklahoma Legislature, Haskell delivered a message creating a commission charged with sending a message to the U.S. Congress: amending the United States Constitution to provide for the election of U.S. senators by a direct vote of the people. Although it did not occur until after he left office, his efforts, as well as the works of the Progressive-era leaders, provided for the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1912.

Though Guthrie was the official capital of the state, Haskell set up his administration from Oklahoma City. Oklahoma City quickly grew in industry and prominence, with a booming population of 64,000, shadowing the smaller city of Guthrie, which was located just miles from the growing city. Haskell personally led the move to change the capital from Guthrie to Oklahoma City. First, he moved the official home of the Great Seal of Oklahoma and Oklahoma Constitution. Slowly, all government functions moved to the Oklahoma City area.

Theodore Roosevelt would be one of Haskell's fiercest political opponents during his Governorship

In the state legislature’s first session, under Haskell’s leadership, Oklahoma adopted laws regulating banking in the state, reformed the old territorial prison system, and protected the public from exploitative railroads, public utilities, trusts and monopolies. Haskell also initiated a law insuring deposits in case of a bank failure, a landmark piece of legislation in the nation. Haskell also rigidly enforced prohibition through the Alcohol Control Act. Though following progressive dogma at every turn, such as the introduction of child labor laws, factory inspection codes, safety codes for mines, health and sanitary laws, and employer’s liability for workers, Haskell’s legislative schedule also included Jim Crow laws for Oklahoma. Haskell's other significant contributions while governor included establishing the Oklahoma Geological Survey, the Oklahoma School for the Blind, the Oklahoma College for Women and the Oklahoma State Department of Health. In addition, he helped to create the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in 1908. Haskell selected the first judges of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals.[3]

Prior to statehood, Kansas officials imprisoned individuals convicted of crimes in Oklahoma Territory. Oklahoma Commissioner of Charities and Corrections Kate Barnard, Oklahoma's first female state official, visited the Kansas prisons and reported to Governor Haskell on the horrible conditions. In response, in 1908, Haskell pushed a bill through the state legislature that transferred 50 Oklahoma prisoners detained in the Kansas penitentiary at Lansing to McAlester, Oklahoma. When the Oklahoma state militia marched the prisoners down to McAlester, they found no prison. Under military supervision, the prisoners built Oklahoma State Penitentiary, the state's first correctional facility (still in use today). The militia housed the prisoners in a tent city and were authorized by Haskell to use lethal force against any prisoner that tried to escape.

A grandfather clause was also enacted by the 2nd Oklahoma Legislature by the state’s Democratic leaders, effectively excluding blacks from voting. Haskell would spend the remainder of his term enforcing prohibition, regulation of railroads and other trusts, and the moving of the state capital to Oklahoma City. Haskell’s dream came true on June 11, 1910, when Oklahoma City became the state’s official capital.

Throughout his term as governor, Haskell remained free from corruption. Though he was the leader in the deliberations of the committee on county lines and county seats, when hundreds of towns had committees attending the sessions with heavy purses, he left these deliberations lean and poor, and by the time he retired from the governor's office he had become utterly impoverished. In debate he ignored the graces of oratory and instead marshaled facts, arrayed statistics and piled up figures, using his cutting wit and grim humor to carry his point.

At the end of his term as governor in 1911, Haskell stepped down from the governorship, happy to see his 1907 Democratic primary challenger Lee Cruce inaugurated as the second governor of Oklahoma. In 1912, Haskell unsuccessfully challenged incumbent U.S. Senator Robert Latham Owen in a hard-fought Democratic primary for his U.S. Senate seat.[4]

National politics

Not only a powerful figure in Oklahoma politics, Haskell’s progressive roots and populist nature granted him national clout. In 1908, Haskell headed the Oklahoma delegation to the National Democratic Convention at Denver and for a few months was Treasurer of the Democratic Campaign Committee. He was the spokesman for William Jennings Bryan in writing the platform of the convention. In 1920, he again headed the Oklahoma delegation at the National Convention, which in that year met at San Francisco, and was committed to and faithfully labored for United States Senator Robert Latham Owen, of Oklahoma, for the United States presidential nomination. Haskell would serve in this post two more times: a third in 1928 to the National Democratic Convention at Houston, and a fourth time in 1932 to the National Democratic Convention at Chicago.

At each convention and in his speeches and in articles appearing in the public press he disclosed an intimate understanding of the big money masters of America and ruthlessly exposed many of their venal practices and their corrupt usage of the public funds in their own interest to the detriment of the people.

Later life, death and legacy

Haskell entered the oil business after finishing his term as governor,[5] a profession he would stay in until the end of his life. In 1933, Haskell suffered a major stroke, from which he would never recover. Three months later Haskell would die from pneumonia. Haskell lost consciousness on July 4, and died the next day, in the Skirvin Hotel in Oklahoma City at the age of 73. He is buried in Muskogee, Oklahoma.[5]

As Oklahoma's first governor, Haskell left a legacy marked by a practical and keen legal mind. Haskell was known for finding the middle ground and usually brought the belligerent partisan forces and rival interests into friendly agreement.

One of his most significant achievements as governor was moving the state capital from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.

Charles Haskell Elementary in Edmond, Oklahoma, and Charles N. Haskell Middle School in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma are named in his honor. Haskell County, Oklahoma and the city of Haskell, Oklahoma were also named for him.

In 2007, Oklahoma celebrated 100 years of statehood. Many descendants of Charles Nathaniel Haskell were in attendance.

State of the State Speeches

- First State of the State

- Second State of the State

- Third State of the State

- Fourth and final State of the State

Sources

- Short biography of Charles N Haskell

- Address of Haskell from the Chronicles of Oklahoma

- Tribute to Haskell from the Chronicles of Oklahoma

References

^ abcdef Compton, J. J. "Haskell, Charles Nathaniel (1860-1933) Archived July 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture Archived May 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Oklahoma Historical Society. (accessed July 17, 2013)

^ A Century to Remember Archived September 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., Oklahoma House of Representatives Archived June 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. (accessed July 17, 2013)

^ Enrolled House Concurrent Resolution No. 25 Archived September 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine., Chronicles of Oklahoma Vol. 11, No. 3, September, 1933. (accessed July 14, 2013)

^ Belcher, Wyatt W. "Political Leadership of Robert L. Owen" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma Vol. 31 (Winter 1953–54) - Oklahoma Historical Society. pp. 361–371..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Oklahoma Governors Archived September 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., Ok.gov. (accessed July 14, 2013)

External links

"Charles Nathaniel Haskell". Oklahoma Governor. Find a Grave. Mar 31, 2002. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

"Oklahoma Governor Charles Nathaniel Haskell". National Governors Association. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Frank Frantz Territorial Governor | Governor of Oklahoma 1907–1911 | Succeeded by Lee Cruce |

Notes and references | ||

1. The position of Governor of Oklahoma was created under the new Oklahoma Constitution. It replaced the office of Governor of Oklahoma Territory. | ||