Jazz

| Jazz | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Late 19th century, Southern United States |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Fusion genres | |

| |

| Regional scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

| |

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, United States,[1] in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and developed from roots in blues and ragtime.[2] Jazz is seen by many as "America's classical music".[3] Since the 1920s Jazz Age, jazz has become recognized as a major form of musical expression. It then emerged in the form of independent traditional and popular musical styles, all linked by the common bonds of African-American and European-American musical parentage with a performance orientation.[4] Jazz is characterized by swing and blue notes, call and response vocals, polyrhythms and improvisation. Jazz has roots in West African cultural and musical expression, and in African-American music traditions including blues and ragtime, as well as European military band music.[5] Intellectuals around the world have hailed jazz as "one of America's original art forms".[6]

As jazz spread around the world, it drew on different national, regional, and local musical cultures, which gave rise to many distinctive styles. New Orleans jazz began in the early 1910s, combining earlier brass-band marches, French quadrilles, biguine, ragtime and blues with collective polyphonic improvisation. In the 1930s, heavily arranged dance-oriented swing big bands, Kansas City jazz, a hard-swinging, bluesy, improvisational style and Gypsy jazz (a style that emphasized musette waltzes) were the prominent styles. Bebop emerged in the 1940s, shifting jazz from danceable popular music toward a more challenging "musician's music" which was played at faster tempos and used more chord-based improvisation. Cool jazz developed near the end of the 1940s, introducing calmer, smoother sounds and long, linear melodic lines.

The 1950s saw the emergence of free jazz, which explored playing without regular meter, beat and formal structures, and in the mid-1950s, hard bop emerged, which introduced influences from rhythm and blues, gospel, and blues, especially in the saxophone and piano playing. Modal jazz developed in the late 1950s, using the mode, or musical scale, as the basis of musical structure and improvisation. Jazz-rock fusion appeared in the late 1960s and early 1970s, combining jazz improvisation with rock music's rhythms, electric instruments, and highly amplified stage sound. In the early 1980s, a commercial form of jazz fusion called smooth jazz became successful, garnering significant radio airplay. Other styles and genres abound in the 2000s, such as Latin and Afro-Cuban jazz.

Contents

1 Etymology and definition

2 Elements and issues

2.1 Improvisation

2.2 Tradition and race

2.3 Roles of women

3 Origins and early history

3.1 Blended African and European music sensibilities

3.2 African rhythmic retention

3.3 "Spanish tinge"—the Afro-Cuban rhythmic influence

3.4 Ragtime

3.5 Blues

3.5.1 African genesis

3.5.2 W. C. Handy: early published blues

3.5.3 Within the context of Western harmony

3.6 New Orleans

3.6.1 Syncopation

3.6.2 Swing in the early 20th century

3.7 Other regions

4 The Jazz Age

4.1 Swing in the 1920s and 1930s

4.2 "American music"—the influence of Ellington

4.3 Beginnings of European jazz

5 Post-war jazz

5.1 Bebop

5.1.1 Rhythm

5.1.2 Harmony

5.2 Afro-Cuban jazz (cu-bop)

5.2.1 Machito and Mario Bauza

5.2.2 Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo

5.2.3 African cross-rhythm

5.3 Dixieland revival

5.4 Cool jazz and West Coast jazz

5.5 Hard bop

5.6 Modal jazz

5.7 Free jazz

5.7.1 Free jazz in Europe

5.8 Latin jazz

5.8.1 Afro-Cuban jazz

5.8.1.1 Guajeos

5.8.1.2 Afro-Cuban jazz renaissance

5.8.2 Afro-Brazilian jazz

5.9 Post-bop

5.10 Soul jazz

5.11 African-inspired

5.11.1 Themes

5.11.2 Rhythm

5.11.3 Pentatonic scales

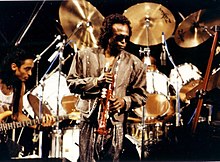

5.12 Jazz fusion

5.12.1 Miles Davis' new directions

5.12.2 Psychedelic-jazz

5.12.2.1 Bitches Brew

5.12.2.2 Herbie Hancock

5.12.2.3 Weather Report

5.12.3 Jazz-rock

5.13 Jazz-funk

5.14 Other trends

5.15 Traditionalism in the 1980s

5.16 Smooth jazz

5.17 Acid jazz, nu jazz and jazz rap

5.18 Punk jazz and jazzcore

5.19 M-Base

5.20 1990s–present

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Etymology and definition

American jazz composer, lyricist, and pianist Eubie Blake made an early contribution to the genre's etymology

Albert Gleizes, 1915, Composition for "Jazz" from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The origin of the word jazz has resulted in considerable research, and its history is well documented. It is believed to be related to jasm, a slang term dating back to 1860 meaning "pep, energy".[7] The earliest written record of the word is in a 1912 article in the Los Angeles Times in which a minor league baseball pitcher described a pitch which he called a jazz ball "because it wobbles and you simply can't do anything with it".[7]

The use of the word in a musical context was documented as early as 1915 in the Chicago Daily Tribune.[8] Its first documented use in a musical context in New Orleans was in a November 14, 1916 Times-Picayune article about "jas bands".[9] In an interview with NPR, musician Eubie Blake offered his recollections of the original slang connotations of the term, saying: "When Broadway picked it up, they called it 'J-A-Z-Z'. It wasn't called that. It was spelled 'J-A-S-S'. That was dirty, and if you knew what it was, you wouldn't say it in front of ladies."[10] The American Dialect Society named it the Word of the Twentieth Century.[11]

Jazz is difficult to define because it encompasses a wide range of music spanning a period of over 100 years, from ragtime to the rock-infused fusion. Attempts have been made to define jazz from the perspective of other musical traditions, such as European music history or African music. But critic Joachim-Ernst Berendt argues that its terms of reference and its definition should be broader,[12] defining jazz as a "form of art music which originated in the United States through the confrontation of the Negro with European music"[13] and arguing that it differs from European music in that jazz has a "special relationship to time defined as 'swing'". Jazz involves "a spontaneity and vitality of musical production in which improvisation plays a role" and contains a "sonority and manner of phrasing which mirror the individuality of the performing jazz musician".[12] In the opinion of Robert Christgau, "most of us would say that inventing meaning while letting loose is the essence and promise of jazz".[14]

A broader definition that encompasses different eras of jazz has been proposed by Travis Jackson: "it is music that includes qualities such as swing, improvising, group interaction, developing an 'individual voice', and being open to different musical possibilities".[15] Krin Gibbard argued that "jazz is a construct" which designates "a number of musics with enough in common to be understood as part of a coherent tradition".[16] In contrast to commentators who have argued for excluding types of jazz, musicians are sometimes reluctant to define the music they play. Duke Ellington, one of jazz's most famous figures, said, "It's all music."[17]

Elements and issues

Improvisation

Double bassist Reggie Workman, saxophone player Pharoah Sanders, and drummer Idris Muhammad performing in 1978

Although jazz is considered difficult to define, in part because it contains many subgenres, improvisation is one of its key elements.[citation needed] The centrality of improvisation is attributed to the influence of earlier forms of music such as blues, a form of folk music which arose in part from the work songs and field hollers of African-American slaves on plantations. These work songs were commonly structured around a repetitive call-and-response pattern, but early blues was also improvisational. Classical music performance is evaluated more by its fidelity to the musical score, with less attention given to interpretation, ornamentation, and accompaniment. The classical performer's goal is to play the composition as it was written. In contrast, jazz is often characterized by the product of interaction and collaboration, placing less value on the contribution of the composer, if there is one, and more on the performer.[18] The jazz performer interprets a tune in individual ways, never playing the same composition twice. Depending on the performer's mood, experience, and interaction with band members or audience members, the performer may change melodies, harmonies, and time signatures.[19]

In early Dixieland, a.k.a. New Orleans jazz, performers took turns playing melodies and improvising countermelodies. In the swing era of the 1920s–'40s, big bands relied more on arrangements which were written or learned by ear and memorized. Soloists improvised within these arrangements. In the bebop era of the 1940s, big bands gave way to small groups and minimal arrangements in which the melody was stated briefly at the beginning and most of the song was improvised. Modal jazz abandoned chord progressions to allow musicians to improvise even more. In many forms of jazz, a soloist is supported by a rhythm section of one or more chordal instruments (piano, guitar), double bass, and drums. The rhythm section plays chords and rhythms that outline the song structure and complement the soloist.[20] In avant-garde and free jazz, the separation of soloist and band is reduced, and there is license, or even a requirement, for the abandoning of chords, scales, and meters.

Tradition and race

Since the emergence of bebop, forms of jazz that are commercially oriented or influenced by popular music have been criticized. According to Bruce Johnson, there has always been a "tension between jazz as a commercial music and an art form".[15] Traditional jazz enthusiasts have dismissed bebop, free jazz, and jazz fusion as forms of debasement and betrayal. An alternative view is that jazz can absorb and transform diverse musical styles.[21] By avoiding the creation of norms, jazz allows avant-garde styles to emerge.[15]

For some African Americans, jazz has drawn attention to African-American contributions to culture and history. For others, jazz is a reminder of "an oppressive and racist society and restrictions on their artistic visions".[22]Amiri Baraka argues that there is a "white jazz" genre that expresses whiteness.[23] White jazz musicians appeared in the midwest and in other areas throughout the U.S. Papa Jack Laine, who ran the Reliance band in New Orleans in the 1910s, was called "the father of white jazz".[24] The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, whose members were white, were the first jazz group to record, and Bix Beiderbecke was one of the most prominent jazz soloists of the 1920s.[25] The Chicago School (or Chicago Style) was developed by white musicians such as Eddie Condon, Bud Freeman, Jimmy McPartland, and Dave Tough. Others from Chicago such as Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa became leading members of swing during the 1930s.[26] Many bands included both black and white musicians. These musicians helped change attitudes toward race in the U.S.[27]

Roles of women

Ethel Waters sang "Stormy Weather" at the Cotton Club.

Betty Carter was known for her improvisational style and scatting.

Female jazz performers and composers have contributed throughout jazz history. Although Betty Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, Adelaide Hall, Billie Holiday, Abbey Lincoln, Anita O'Day, Dinah Washington, and Ethel Waters were recognized for their vocal talent, women received less recognition for their accomplishments as bandleaders, composers, and instrumentalists. This group includes pianist Lil Hardin Armstrong and songwriters Irene Higginbotham and Dorothy Fields. Women began playing instruments in jazz in the early 1920s, drawing particular recognition on piano.[28] Popular musicians of the time were Lovie Austin, Sweet Emma Barrett, Jeanette Kimball, Billie Pierce, Mary Lou Williams

When male jazz musicians were drafted during World War II, many all-female bands took over.[28]The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, which was founded in 1937, was a popular band that became the first all-female integrated band in the U.S. and the first to travel with the USO, touring Europe in 1945. Women were members of the big bands of Woody Herman and Gerald Wilson. From the 1950s onwards many women jazz instrumentalists became prominent, some sustaining lengthy careers. Over the decades, some of the most distinctive improvisers, composers and bandleaders in jazz have been women.[29]

Origins and early history

Jazz originated in the late 19th to early 20th century as interpretations of American and European classical music entwined with African and slave folk songs and the influences of West African culture.[30] Its composition and style have changed many times throughout the years with each performer's personal interpretation and improvisation, which is also one of the greatest appeals of the genre.[31]

Blended African and European music sensibilities

Dance in Congo Square in the late 1700s, artist's conception by E. W. Kemble from a century later

In the late 18th-century painting The Old Plantation, African-Americans dance to banjo and percussion.

By the 18th century, slaves gathered socially at a special market, in an area which later became known as Congo Square, famous for its African dances.[32]

By 1866, the Atlantic slave trade had brought nearly 400,000 Africans to North America.[33] The slaves came largely from West Africa and the greater Congo River basin and brought strong musical traditions with them.[34] The African traditions primarily use a single-line melody and call-and-response pattern, and the rhythms have a counter-metric structure and reflect African speech patterns.[35]

An 1885 account says that they were making strange music (Creole) on an equally strange variety of 'instruments'—washboards, washtubs, jugs, boxes beaten with sticks or bones and a drum made by stretching skin over a flour-barrel.[3][36]

Lavish festivals featuring African-based dances to drums were organized on Sundays at Place Congo, or Congo Square, in New Orleans until 1843.[37] There are historical accounts of other music and dance gatherings elsewhere in the southern United States. Robert Palmer said of percussive slave music:

Usually such music was associated with annual festivals, when the year's crop was harvested and several days were set aside for celebration. As late as 1861, a traveler in North Carolina saw dancers dressed in costumes that included horned headdresses and cow tails and heard music provided by a sheepskin-covered "gumbo box", apparently a frame drum; triangles and jawbones furnished the auxiliary percussion. There are quite a few [accounts] from the southeastern states and Louisiana dating from the period 1820–1850. Some of the earliest [Mississippi] Delta settlers came from the vicinity of New Orleans, where drumming was never actively discouraged for very long and homemade drums were used to accompany public dancing until the outbreak of the Civil War.[38]

Another influence came from the harmonic style of hymns of the church, which black slaves had learned and incorporated into their own music as spirituals.[39] The origins of the blues are undocumented, though they can be seen as the secular counterpart of the spirituals. However, as Gerhard Kubik points out, whereas the spirituals are homophonic, rural blues and early jazz "was largely based on concepts of heterophony."[40]

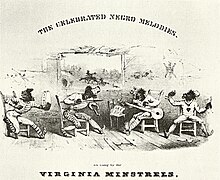

The blackface Virginia Minstrels in 1843, featuring tambourine, fiddle, banjo and bones

During the early 19th century an increasing number of black musicians learned to play European instruments, particularly the violin, which they used to parody European dance music in their own cakewalk dances. In turn, European-American minstrel show performers in blackface popularized the music internationally, combining syncopation with European harmonic accompaniment. In the mid-1800s the white New Orleans composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk adapted slave rhythms and melodies from Cuba and other Caribbean islands into piano salon music. New Orleans was the main nexus between the Afro-Caribbean and African-American cultures.

African rhythmic retention

The "Black Codes" outlawed drumming by slaves, which meant that African drumming traditions were not preserved in North America, unlike in Cuba, Haiti, and elsewhere in the Caribbean. African-based rhythmic patterns were retained in the United States in large part through "body rhythms" such as stomping, clapping, and patting juba dancing.[41]

In the opinion of jazz historian Ernest Borneman, what preceded New Orleans jazz before 1890 was "Afro-Latin music", similar to what was played in the Caribbean at the time.[42] A three-stroke pattern known in Cuban music as tresillo is a fundamental rhythmic figure heard in many different slave musics of the Caribbean, as well as the Afro-Caribbean folk dances performed in New Orleans Congo Square and Gottschalk's compositions (for example "Souvenirs From Havana" (1859)). Tresillo is the most basic and most prevalent duple-pulse rhythmic cell in sub-Saharan African music traditions and the music of the African Diaspora.[43][44]

Tresillo.[45][46]

Tresillo is heard prominently in New Orleans second line music and in other forms of popular music from that city from the turn of the 20th century to present.[47] "By and large the simpler African rhythmic patterns survived in jazz ... because they could be adapted more readily to European rhythmic conceptions," jazz historian Gunther Schuller observed. "Some survived, others were discarded as the Europeanization progressed."[48]

In the post-Civil War period (after 1865), African Americans were able to obtain surplus military bass drums, snare drums and fifes, and an original African-American drum and fife music emerged, featuring tresillo and related syncopated rhythmic figures.[49] This was a drumming tradition that was distinct from its Caribbean counterparts, expressing a uniquely African-American sensibility. "The snare and bass drummers played syncopated cross-rhythms," observed the writer Robert Palmer, speculating that "this tradition must have dated back to the latter half of the nineteenth century, and it could have not have developed in the first place if there hadn't been a reservoir of polyrhythmic sophistication in the culture it nurtured."[41]

"Spanish tinge"—the Afro-Cuban rhythmic influence

African-American music began incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythmic motifs in the 19th century when the habanera (Cuban contradanza) gained international popularity.[50] Musicians from Havana and New Orleans would take the twice-daily ferry between both cities to perform, and the habanera quickly took root in the musically fertile Crescent City. John Storm Roberts states that the musical genre habanera "reached the U.S. twenty years before the first rag was published."[51] For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime, and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the habanera was a consistent part of African-American popular music.[52]

Habaneras were widely available as sheet music and were the first written music which was rhythmically based on an African motif (1803).[53] From the perspective of African-American music, the habanera rhythm (also known as congo,[54]tango-congo,[55] or tango.[56]) can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.[57] The habanera was the first of many Cuban music genres which enjoyed periods of popularity in the United States and reinforced and inspired the use of tresillo-based rhythms in African-American music.

Habanera rhythm written as a combination of tresillo (bottom notes) with the backbeat (top note)

New Orleans native Louis Moreau Gottschalk's piano piece "Ojos Criollos (Danse Cubaine)" (1860) was influenced by the composer's studies in Cuba: the habanera rhythm is clearly heard in the left hand.[58] In Gottschalk's symphonic work "A Night in the Tropics" (1859), the tresillo variant cinquillo appears extensively.[59] The figure was later used by Scott Joplin and other ragtime composers.

Cinquillo.

Comparing the music of New Orleans with the music of Cuba, Wynton Marsalis observes that tresillo is the New Orleans "clave", a Spanish word meaning 'code' or 'key', as in the key to a puzzle, or mystery.[60] Although technically the pattern is only half a clave, Marsalis makes the point that the single-celled figure is the guide-pattern of New Orleans music. Jelly Roll Morton called the rhythmic figure the Spanish tinge and considered it an essential ingredient of jazz.[61]

Ragtime

Scott Joplin in 1903

The abolition of slavery in 1865 led to new opportunities for the education of freed African Americans. Although strict segregation limited employment opportunities for most blacks, many were able to find work in entertainment. Black musicians were able to provide entertainment in dances, minstrel shows, and in vaudeville, during which time many marching bands were formed. Black pianists played in bars, clubs, and brothels, as ragtime developed.[62][63]

Ragtime appeared as sheet music, popularized by African-American musicians such as the entertainer Ernest Hogan, whose hit songs appeared in 1895. Two years later, Vess Ossman recorded a medley of these songs as a banjo solo known as "Rag Time Medley".[64][65] Also in 1897, the white composer William H. Krell published his "Mississippi Rag" as the first written piano instrumental ragtime piece, and Tom Turpin published his "Harlem Rag", the first rag published by an African-American.

The classically trained pianist Scott Joplin produced his "Original Rags" in 1898 and, in 1899, had an international hit with "Maple Leaf Rag", a multi-strain ragtime march with four parts that feature recurring themes and a bass line with copious seventh chords. Its structure was the basis for many other rags, and the syncopations in the right hand, especially in the transition between the first and second strain, were novel at the time.[66]

Excerpt from "Maple Leaf Rag" by Scott Joplin (1899), seventh chord resolution[67]

African-based rhythmic patterns such as tresillo and its variants, the habanera rhythm and cinquillo, are heard in the ragtime compositions of Joplin, Turpin, and others. Joplin's "Solace" (1909) is generally considered to be within the habanera genre:[54][68] both of the pianist's hands play in a syncopated fashion, completely abandoning any sense of a march rhythm. Ned Sublette postulates that the tresillo/habanera rhythm "found its way into ragtime and the cakewalk,"[69] whilst Roberts suggests that "the habanera influence may have been part of what freed black music from ragtime's European bass."[70]

Blues

African genesis

Blues is the name given to both a musical form and a music genre,[71] which originated in African-American communities of primarily the "Deep South" of the United States at the end of the 19th century from their spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts and chants and rhymed simple narrative ballads.[72]

The African use of pentatonic scales contributed to the development of blue notes in blues and jazz.[73] As Kubik explains:

Many of the rural blues of the Deep South are stylistically an extension and merger of basically two broad accompanied song-style traditions in the west central Sudanic belt:

- A strongly Arabic/Islamic song style, as found for example among the Hausa. It is characterized by melisma, wavy intonation, pitch instabilities within a pentatonic framework, and a declamatory voice.

- An ancient west central Sudanic stratum of pentatonic song composition, often associated with simple work rhythms in a regular meter, but with notable off-beat accents (1999: 94).[74]

W. C. Handy: early published blues

W. C. Handy at 19, 1892

W. C. Handy became intrigued by the folk blues of the Deep South whilst traveling through the Mississippi Delta. In this folk blues form, the singer would improvise freely within a limited melodic range, sounding like a field holler, and the guitar accompaniment was slapped rather than strummed, like a small drum which responded in syncopated accents, functioning as another "voice".[75] Handy and his band members were formally trained African-American musicians who had not grown up with the blues, yet he was able to adapt the blues to a larger band instrument format and arrange them in a popular music form.

Handy wrote about his adopting of the blues:

The primitive southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor. Whether in the cotton field of the Delta or on the Levee up St. Louis way, it was always the same. Till then, however, I had never heard this slur used by a more sophisticated Negro, or by any white man. I tried to convey this effect ... by introducing flat thirds and sevenths (now called blue notes) into my song, although its prevailing key was major ..., and I carried this device into my melody as well.[76]

The publication of his "Memphis Blues" sheet music in 1912 introduced the 12-bar blues to the world (although Gunther Schuller argues that it is not really a blues, but "more like a cakewalk"[77]). This composition, as well as his later "St. Louis Blues" and others, included the habanera rhythm,[78] and would become jazz standards. Handy's music career began in the pre-jazz era and contributed to the codification of jazz through the publication of some of the first jazz sheet music.

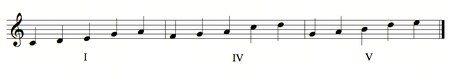

Within the context of Western harmony

The blues form which is ubiquitous in jazz is characterized by specific chord progressions, of which the twelve-bar blues progression is the most common. Basic blues progressionions are based on the I, IV and V chords (often called the "one", "four" and "five" chords). An important part of the sound are the microtonal blue notes which, for expressive purposes, are sung or played flattened (thus "between" the notes on a piano), or gradually "bent" (minor third to major third) in relation to the pitch of the major scale. The blue notes opened up an entirely new approach to Western harmony, ultimately leading to a high level of harmonic complexity in jazz.[citation needed]

New Orleans

The Bolden Band around 1905

The music of New Orleans had a profound effect on the creation of early jazz. The reason why jazz is mainly associated with New Orleans is due to the slaves being able to practice elements of their culture such as voodoo, and they were also allowed drums.[79] Many early jazz performers played in venues throughout the city, such as the brothels and bars of the red-light district around Basin Street, known as "Storyville".[80] In addition to dance bands, there were numerous marching bands who played at lavish funerals (later called jazz funerals), which were arranged by the African-American and European-American communities. The instruments used in marching bands and dance bands became the basic instruments of jazz: brass, reeds tuned in the European 12-tone scale, and drums. Small bands which mixed self-taught and well-educated African-American musicians, many of whom came from the funeral procession tradition of New Orleans, played a seminal role in the development and dissemination of early jazz. These bands travelled throughout Black communities in the Deep South and, from around 1914 onwards, Afro-Creole and African-American musicians played in vaudeville shows which took jazz to western and northern US cities.[81]

Jelly Roll Morton, in Los Angeles, California, c. 1917 or 1918

In New Orleans, a white marching band leader named Papa Jack Laine integrated blacks and whites in his marching band. Laine was known as "the father of white jazz" because of the many top players who passed through his bands (including George Brunies, Sharkey Bonano and the future members of the Original Dixieland Jass Band). Laine was a good talent scout. During the early 1900s, jazz was mostly done in the African-American and mulatto communities, due to segregation laws. The red light district of Storyville, New Orleans was crucial in bringing jazz music to a wider audience via tourists who came to the port city.[82] Many jazz musicians from the African-American communities were hired to perform live music in brothels and bars, including many early jazz pioneers such as Buddy Bolden and Jelly Roll Morton, in addition to those from New Orleans other communities such as Lorenzo Tio and Alcide Nunez. Louis Armstrong also got his start in Storyville[83] and would later find success in Chicago (along with others from New Orleans) after the United States government shut down Storyville in 1917.[84]

Syncopation

The cornetist Buddy Bolden led a band who are often mentioned as one of the prime originators of the style later to be called "jazz". He played in New Orleans around 1895–1906, before developing a mental illness; there are no recordings of him playing. Bolden's band is credited with creating the big four, the first syncopated bass drum pattern to deviate from the standard on-the-beat march.[85] As the example below shows, the second half of the big four pattern is the habanera rhythm.

Buddy Bolden's "big four" pattern[86]

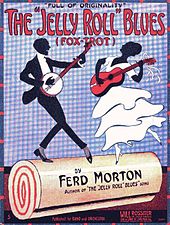

Morton published "Jelly Roll Blues" in 1915, the first jazz work in print.

Afro-Creole pianist Jelly Roll Morton began his career in Storyville. From 1904, he toured with vaudeville shows around southern cities, also playing in Chicago and New York City. In 1905, he composed his "Jelly Roll Blues", which on its publication in 1915 became the first jazz arrangement in print, introducing more musicians to the New Orleans style.[87]

Morton considered the tresillo/habanera (which he called the Spanish tinge) to be an essential ingredient of jazz.[88] In his own words:

Now in one of my earliest tunes, "New Orleans Blues," you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can't manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz.[61]

Excerpt from Jelly Roll Morton's "New Orleans Blues" (c. 1902). The left hand plays the tresillo rhythm. The right hand plays variations on cinquillo.

Morton was a crucial innovator in the evolution from the early jazz form known as ragtime to jazz piano, and could perform pieces in either style; in 1938, Morton made a series of recordings for the Library of Congress, in which he demonstrated the difference between the two styles. Morton's solos, however, were still close to ragtime, and were not merely improvisations over chord changes as in later jazz, but his use of the blues was of equal importance.

Swing in the early 20th century

Bottom: even duple subdivisions of the beat Top: swung correlative—contrasting of duple and triple subdivisions of the beat

Morton loosened ragtime's rigid rhythmic feeling, decreasing its embellishments and employing a swing feeling.[89] Swing is the most important and enduring African-based rhythmic technique used in jazz. An oft quoted definition of swing by Louis Armstrong is: "if you don't feel it, you'll never know it."[90]The New Harvard Dictionary of Music states that swing is: "An intangible rhythmic momentum in jazz ... Swing defies analysis; claims to its presence may inspire arguments." The dictionary does nonetheless provide the useful description of triple subdivisions of the beat contrasted with duple subdivisions:[91] swing superimposes six subdivisions of the beat over a basic pulse structure or four subdivisions. This aspect of swing is far more prevalent in African-American music than in Afro-Caribbean music. One aspect of swing, which is heard in more rhythmically complex Diaspora musics, places strokes in-between the triple and duple-pulse "grids".[92]

Sheet music for "Livery Stable Blues"/"Barnyard Blues" by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Leo Feist, Inc., New York, copyright 1917

New Orleans brass bands are a lasting influence, contributing horn players to the world of professional jazz with the distinct sound of the city whilst helping black children escape poverty. The leader of New Orleans' Camelia Brass Band, D'Jalma Ganier, taught Louis Armstrong to play trumpet; Armstrong would then popularize the New Orleans style of trumpet playing, and then expand it. Like Jelly Roll Morton, Armstrong is also credited with the abandonment of ragtime's stiffness in favor of swung notes. Armstrong, perhaps more than any other musician, codified the rhythmic technique of swing in jazz and broadened the jazz solo vocabulary.[93]

The Original Dixieland Jass Band made the music's first recordings early in 1917, and their "Livery Stable Blues" became the earliest released jazz record.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100] That year, numerous other bands made recordings featuring "jazz" in the title or band name, but most were ragtime or novelty records rather than jazz. In February 1918 during World War I, James Reese Europe's "Hellfighters" infantry band took ragtime to Europe,[101][102] then on their return recorded Dixieland standards including "Darktown Strutters' Ball".[103]

Other regions

In the northeastern United States, a "hot" style of playing ragtime had developed, notably James Reese Europe's symphonic Clef Club orchestra in New York City, which played a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall in 1912.[103][104] The Baltimore rag style of Eubie Blake influenced James P. Johnson's development of stride piano playing, in which the right hand plays the melody, while the left hand provides the rhythm and bassline.[105]

In Ohio and elsewhere in the midwest the major influence was ragtime, until about 1919. Around 1912, when the four-string banjo and saxophone came in, musicians began to improvise the melody line, but the harmony and rhythm remained unchanged. A contemporary account states that blues could only be heard in jazz in the gut-bucket cabarets, which were generally looked down upon by the Black middle-class.[106]

The Jazz Age

| Jazz Me Blues The Original Dixieland Jass Band performing "Jazz Me Blues", an example of a jazz piece from 1921 |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The King & Carter Jazzing Orchestra photographed in Houston, Texas, January 1921

From 1920 to 1933, Prohibition in the United States banned the sale of alcoholic drinks, resulting in illicit speakeasies which became lively venues of the "Jazz Age", hosting popular music including current dance songs, novelty songs, and show tunes. Jazz began to get a reputation as being immoral, and many members of the older generations saw it as threatening the old cultural values and promoting the new decadent values of the Roaring 20s. Henry van Dyke of Princeton University wrote, "... it is not music at all. It's merely an irritation of the nerves of hearing, a sensual teasing of the strings of physical passion."[107] The media too began to denigrate jazz. The New York Times used stories and headlines to pick at jazz: Siberian villagers were said by the paper to have used jazz to scare off bears when, in fact, they had used pots and pans; another story claimed that the fatal heart attack of a celebrated conductor was caused by jazz.[107]

In 1919, Kid Ory's Original Creole Jazz Band of musicians from New Orleans began playing in San Francisco and Los Angeles, where in 1922 they became the first black jazz band of New Orleans origin to make recordings.[108][109] That year also saw the first recording by Bessie Smith, the most famous of the 1920s blues singers.[110] Chicago meanwhile was developing the new "Hot Jazz", where King Oliver joined Bill Johnson. Bix Beiderbecke formed The Wolverines in 1924.

Despite its Southern black origins, there was a larger market for jazzy dance music played by white orchestras. In 1918, Paul Whiteman and his orchestra became a hit in San Francisco, California, signing with Victor Talking Machine Company in 1920 and becoming the top bandleader of the 1920s, giving "hot jazz" a white component, hiring white musicians including Bix Beiderbecke, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Frankie Trumbauer, and Joe Venuti. In 1924, Whiteman commissioned Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which was premiered by his orchestra and jazz began to be recognized as a notable musical form. Olin Downes, reviewing the concert in The New York Times: "This composition shows extraordinary talent, as it shows a young composer with aims that go far beyond those of his ilk, struggling with a form of which he is far from being master.... In spite of all this, he has expressed himself in a significant and, on the whole, highly original form.... His first theme ... is no mere dance-tune ... it is an idea, or several ideas, correlated and combined in varying and contrasting rhythms that immediately intrigue the listener."[111]

After Whiteman's band successfully toured Europe, huge hot jazz orchestras in theater pits caught on with other whites, including Fred Waring, Jean Goldkette, and Nathaniel Shilkret. According to Mario Dunkel, Whiteman's success was based on a "rhetoric of domestication" according to which he had elevated and rendered valuable (read "white") a previously inchoate (read "black") kind of music.[112] Whiteman's success caused blacks to follow suit, including Earl Hines (who opened in The Grand Terrace Cafe in Chicago in 1928), Duke Ellington (who opened at the Cotton Club in Harlem in 1927), Lionel Hampton, Fletcher Henderson, Claude Hopkins, and Don Redman, with Henderson and Redman developing the "talking to one another" formula for "hot" Swing music.[113]

Trumpeter, composer and singer Louis Armstrong began his career in New Orleans and became one of jazz's most recognizable performers.

In 1924, Louis Armstrong joined the Fletcher Henderson dance band for a year, as featured soloist. The original New Orleans style was polyphonic, with theme variation and simultaneous collective improvisation. Armstrong was a master of his hometown style, but by the time he joined Henderson's band, he was already a trailblazer in a new phase of jazz, with its emphasis on arrangements and soloists. Armstrong's solos went well beyond the theme-improvisation concept and extemporized on chords, rather than melodies. According to Schuller, by comparison, the solos by Armstrong's bandmates (including a young Coleman Hawkins), sounded "stiff, stodgy," with "jerky rhythms and a grey undistinguished tone quality."[114] The following example shows a short excerpt of the straight melody of "Mandy, Make Up Your Mind" by George W. Meyer and Arthur Johnston (top), compared with Armstrong's solo improvisations (below) (recorded 1924).[115] (The example approximates Armstrong's solo, as it doesn't convey his use of swing.)

Top: excerpt from the straight melody of "Mandy, Make Up Your Mind" by George W. Meyer & Arthur Johnston. Bottom: corresponding solo excerpt by Louis Armstrong (1924).

Armstrong's solos were a significant factor in making jazz a true 20th-century language. After leaving Henderson's group, Armstrong formed his virtuosic Hot Five band, where he popularized scat singing.[116]

Jelly Roll Morton recorded with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings in an early mixed-race collaboration, then in 1926 formed his Red Hot Peppers.

Also in the 1920s Skiffle, jazz played with homemade instruments such as washboard, jugs, musical saw, kazoos, etc. began to be recorded in Chicago, later merging with country music.

Swing in the 1920s and 1930s

Benny Goodman (1943)

The 1930s belonged to popular swing big bands, in which some virtuoso soloists became as famous as the band leaders. Key figures in developing the "big" jazz band included bandleaders and arrangers Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Harry James, Jimmie Lunceford, Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw. Although it was a collective sound, swing also offered individual musicians a chance to "solo" and improvise melodic, thematic solos which could at times be very complex "important" music.

Swing was also dance music. It was broadcast on the radio "live" nightly across America for many years, especially by Earl Hines and his Grand Terrace Cafe Orchestra broadcasting coast-to-coast from Chicago[117] (well placed for "live" US time-zones).

Over time, social strictures regarding racial segregation began to relax in America: white bandleaders began to recruit black musicians and black bandleaders white ones. In the mid-1930s, Benny Goodman hired pianist Teddy Wilson, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton and guitarist Charlie Christian to join small groups. In the 1930s, Kansas City Jazz as exemplified by tenor saxophonist Lester Young marked the transition from big bands to the bebop influence of the 1940s. An early 1940s style known as "jumping the blues" or jump blues used small combos, uptempo music and blues chord progressions, drawing on boogie-woogie from the 1930s.

"American music"—the influence of Ellington

Duke Ellington at the Hurricane Club (1943)

While swing was reaching the height of its popularity, Duke Ellington spent the late 1920s and 1930s developing an innovative musical idiom for his orchestra. Abandoning the conventions of swing, he experimented with orchestral sounds, harmony, and musical form with complex compositions that still translated well for popular audiences; some of his tunes became hits, and his own popularity spanned from the United States to Europe.[118]

Ellington called his music "American Music" rather than jazz, and liked to describe those who impressed him as "beyond category."[119] These included many of the musicians who were members of his orchestra, some of whom are considered among the best in jazz in their own right, but it was Ellington who melded them into one of the most popular jazz orchestras in the history of jazz. He often composed specifically for the style and skills of these individuals, such as "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "Concerto for Cootie" for Cootie Williams (which later became "Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me" with Bob Russell's lyrics), and "The Mooche" for Tricky Sam Nanton and Bubber Miley. He also recorded songs written by his bandsmen, such as Juan Tizol's "Caravan" and "Perdido", which brought the "Spanish Tinge" to big-band jazz. Several members of the orchestra remained with him for several decades. The band reached a creative peak in the early 1940s, when Ellington and a small hand-picked group of his composers and arrangers wrote for an orchestra of distinctive voices who displayed tremendous creativity.[120]

Beginnings of European jazz

As only a limited number of American jazz records were released in Europe, European jazz traces many of its roots to American artists such as James Reese Europe, Paul Whiteman, and Lonnie Johnson, who visited Europe during and after World War I. It was their live performances which inspired European audiences' interest in jazz, as well as the interest in all things American (and therefore exotic) which accompanied the economic and political woes of Europe during this time.[121] The beginnings of a distinct European style of jazz began to emerge in this interwar period.

British jazz began with a tour by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1919. In 1926, Fred Elizalde and His Cambridge Undergraduates began broadcasting on the BBC. Thereafter jazz became an important element in many leading dance orchestras and jazz instrumentalists quickly became numerous.[122]

This distinct style entered full swing in France with the Quintette du Hot Club de France, which began in 1934. Much of this French jazz was a combination of African-American jazz and the symphonic styles in which French musicians were well-trained; in this, it is easy to see the inspiration taken from Paul Whiteman since his style was also a fusion of the two.[123] Belgian guitar virtuoso Django Reinhardt popularized gypsy jazz, a mix of 1930s American swing, French dance hall "musette" and Eastern European folk with a languid, seductive feel; the main instruments are steel stringed guitar, violin, and double bass, and solos pass from one player to another as the guitar and bass play the role of the rhythm section. Some music researchers hold that it was Philadelphia's Eddie Lang and Joe Venuti who pioneered the guitar-violin partnership typical of the genre,[124] which was brought to France after they had been heard live or on Okeh Records in the late 1920s.[125]

Post-war jazz

The outbreak of World War II marked a turning point for jazz. The swing-era jazz of the previous decade had challenged other popular music as being representative of the nation's culture, with big bands reaching the height of the style's success by the early 1940s; swing acts and big bands traveled with U.S. military overseas to Europe, where it also became popular.[126] Stateside, however, the war presented difficulties for the big-band format: conscription shortened the number of musicians available; the military's need for shellac (commonly used for pressing gramophone records) limited record production; a shortage of rubber (also due to the war effort) discouraged bands from touring via road travel; and a demand by the musicians' union for a commercial recording ban limited music distribution between 1942 and 1944.[127]

Many of the big bands who were deprived of experienced musicians because of the war effort began to enlist young players who were below the age for conscription, as was the case with saxophonist Stan Getz's entry in a band as a teenager.[128] This coincided with a nationwide resurgence in the Dixieland style of pre-swing jazz; performers such as clarinetist George Lewis, cornetist Bill Davison, and trombonist Turk Murphy were hailed by conservative jazz critics as more authentic than the big bands.[127] Elsewhere, with the limitations on recording, small groups of young musicians developed a more uptempo, improvisational style of jazz,[126] collaborating and experimenting with new ideas for melodic development, rhythmic language, and harmonic substitution, during informal, late-night jam sessions hosted in small clubs and apartments. Key figures in this development were largely based in New York and included pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, drummers Max Roach and Kenny Clarke, saxophonist Charlie Parker, and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie.[127] This musical development became known as bebop.[126]

Bebop and subsequent post-war jazz developments featured a wider set of notes, played in more complex patterns and at faster tempos than previous jazz.[128] According to Clive James, bebop was "the post-war musical development which tried to ensure that jazz would no longer be the spontaneous sound of joy ... Students of race relations in America are generally agreed that the exponents of post-war jazz were determined, with good reason, to present themselves as challenging artists rather than tame entertainers."[129] The end of the war marked "a revival of the spirit of experimentation and musical pluralism under which it had been conceived", along with "the beginning of a decline in the popularity of jazz music in America", according to American academic Michael H. Burchett.[126]

With the rise of bebop and the end of the swing era after the war, jazz lost its cachet as pop music. Vocalists of the famous big bands moved on to being marketed and performing as solo pop singers; these included Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Dick Haymes, and Doris Day.[128] Older musicians who still performed their pre-war jazz, such as Armstrong and Ellington, were gradually viewed in the mainstream as passé. Other younger performers, such as singer Big Joe Turner and saxophonist Louis Jordan, who were discouraged by bebop's increasing complexity pursued more lucrative endeavors in rhythm and blues, jump blues, and eventually rock and roll.[126] Some, including Gillespie, composed intricate yet danceable songs for bebop musicians in an effort to make them more accessible, but bebop largely remained on the fringes of American audiences' purview. "The new direction of postwar jazz drew a wealth of critical acclaim, but it steadily declined in popularity as it developed a reputation as an academic genre that was largely inaccessible to mainstream audiences", Burchett said. "The quest to make jazz more relevant to popular audiences, while retaining its artistic integrity, is a constant and prevalent theme in the history of postwar jazz."[126] During its swing period, jazz had been an uncomplicated musical scene; according to Paul Trynka, this changed in the post-war years:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"Suddenly jazz was no longer straightforward. There was bebop and its variants, there was the last gasp of swing, there were strange new brews like the progressive jazz of Stan Kenton, and there was a completely new phenomenon called revivalism -- the rediscovery of jazz from the past, either on old records or performed live by ageing players brought out of retirement. From now on it was no good saying that you liked jazz, you had to specify what kind of jazz. And that it the way it has been ever since, only more so. Today, the word 'jazz' is virtually meaningless without further definition."[128]

Bebop

Thelonious Monk at Minton's Playhouse, 1947, New York City

Earl Hines 1947

In the early 1940s, bebop-style performers began to shift jazz from danceable popular music toward a more challenging "musician's music." The most influential bebop musicians included saxophonist Charlie Parker, pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Clifford Brown, and drummer Max Roach. Divorcing itself from dance music, bebop established itself more as an art form, thus lessening its potential popular and commercial appeal.

Composer Gunther Schuller wrote:

... In 1943 I heard the great Earl Hines band which had Bird in it and all those other great musicians. They were playing all the flatted fifth chords and all the modern harmonies and substitutions and Dizzy Gillespie runs in the trumpet section work. Two years later I read that that was 'bop' and the beginning of modern jazz ... but the band never made recordings.[130]

Dizzy Gillespie wrote:

... People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit.[131]

Rhythm

Since bebop was meant to be listened to, not danced to, it could use faster tempos. Drumming shifted to a more elusive and explosive style, in which the ride cymbal was used to keep time while the snare and bass drum were used for accents. This led to a highly syncopated music with a linear rhythmic complexity.[132]

Harmony

Charlie Parker, Tommy Potter, Miles Davis, Max Roach (Gottlieb 06941)

Bebop musicians employed several harmonic devices which were not previously typical in jazz, engaging in a more abstracted form of chord-based improvisation. Bebop scales are traditional scales with an added chromatic passing note;[133] bebop also uses "passing" chords, substitute chords, and altered chords. New forms of chromaticism and dissonance were introduced into jazz, and the dissonant tritone (or "flatted fifth") interval became the "most important interval of bebop"[134] Chord progressions for bebop tunes were often taken directly from popular swing-era songs and reused with a new and more complex melody and/or reharmonized with more complex chord progressions to form new compositions, a practice which was already well-established in earlier jazz, but came to be central to the bebop style. Bebop made use of several relatively common chord progressions, such as blues (at base, I-IV-V, but often infused with ii-V motion) and 'rhythm changes' (I-VI-ii-V) - the chords to the 1930s pop standard "I Got Rhythm." Late bop also moved towards extended forms that represented a departure from pop and show tunes.

The harmonic development in bebop is often traced back to a transcendent moment experienced by Charlie Parker while performing "Cherokee" at Clark Monroe's Uptown House, New York, in early 1942:

I'd been getting bored with the stereotyped changes that were being used, ... and I kept thinking there's bound to be something else. I could hear it sometimes. I couldn't play it.... I was working over 'Cherokee,' and, as I did, I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes, I could play the thing I'd been hearing. It came alive—Parker.[135]

Gerhard Kubik postulates that the harmonic development in bebop sprang from the blues and other African-related tonal sensibilities, rather than 20th-century Western art music as some have suggested:

Auditory inclinations were the African legacy in [Parker's] life, reconfirmed by the experience of the blues tonal system, a sound world at odds with the Western diatonic chord categories. Bebop musicians eliminated Western-style functional harmony in their music while retaining the strong central tonality of the blues as a basis for drawing upon various African matrices.[136]

Samuel Floyd states that blues were both the bedrock and propelling force of bebop, bringing about three main developments:

- A new harmonic conception, using extended chord structures that led to unprecedented harmonic and melodic variety.

- A developed and even more highly syncopated, linear rhythmic complexity and a melodic angularity in which the blue note of the fifth degree was established as an important melodic-harmonic device.

- The reestablishment of the blues as the music's primary organizing and functional principle.[132]

As Kubik explained:

While for an outside observer, the harmonic innovations in bebop would appear to be inspired by experiences in Western "serious" music, from Claude Debussy to Arnold Schoenberg, such a scheme cannot be sustained by the evidence from a cognitive approach. Claude Debussy did have some influence on jazz, for example, on Bix Beiderbecke's piano playing. And it is also true that Duke Ellington adopted and reinterpreted some harmonic devices in European contemporary music. West Coast jazz would run into such debts as would several forms of cool jazz, but bebop has hardly any such debts in the sense of direct borrowings. On the contrary, ideologically, bebop was a strong statement of rejection of any kind of eclecticism, propelled by a desire to activate something deeply buried in self. Bebop then revived tonal-harmonic ideas transmitted through the blues and reconstructed and expanded others in a basically non-Western harmonic approach. The ultimate significance of all this is that the experiments in jazz during the 1940s brought back to African-American music several structural principles and techniques rooted in African traditions[137]

These divergences from the jazz mainstream of the time initially met with a divided, sometimes hostile, response among fans and fellow musicians, especially established swing players, who bristled at the new harmonic sounds. To hostile critics, bebop seemed to be filled with "racing, nervous phrases".[138] But despite the initial friction, by the 1950s, bebop had become an accepted part of the jazz vocabulary.

Afro-Cuban jazz (cu-bop)

Machito (maracas) and his sister Graciella Grillo (claves)

Machito and Mario Bauza

The general consensus among musicians and musicologists is that the first original jazz piece to be overtly based in clave was "Tanga" (1943), composed by Cuban-born Mario Bauza and recorded by Machito and his Afro-Cubans in New York City. "Tanga" began as a spontaneous descarga (Cuban jam session), with jazz solos superimposed on top.[139]

This was the birth of Afro-Cuban jazz. The use of clave brought the African timeline, or key pattern, into jazz. Music organized around key patterns convey a two-celled (binary) structure, which is a complex level of African cross-rhythm.[140] Within the context of jazz, however, harmony is the primary referent, not rhythm. The harmonic progression can begin on either side of clave, and the harmonic "one" is always understood to be "one". If the progression begins on the "three-side" of clave, it is said to be in 3-2 clave. If the progression begins on the "two-side", its in 2-3 clave.[141]

Clave: Spanish for 'code,' or key,' as in the key to a puzzle. The antecedent half (three-side) consists of tresillo. The consequent half consists of two strokes (the two-side).

Bobby Sanabria mentions several innovations of Machito's Afro-Cubans, citing them as the first band: to wed big band jazz arranging techniques within an original composition, with jazz oriented soloists utilizing an authentic Afro-Cuban based rhythm section in a successful manner; to explore modal harmony (a concept explored much later by Miles Davis and Gil Evans) from a jazz arranging perspective; and to overtly explore the concept of clave counterpoint from an arranging standpoint (the ability to weave seamlessly from one side of the clave to the other without breaking its rhythmic integrity within the structure of a musical arrangement). They were also the first band in the United States to use the term "Afro-Cuban" as the band's moniker, thus identifying itself and acknowledging the West African roots of the musical form they were playing. It forced New York City's Latino and African-American communities to deal with their common West African musical roots in a direct way, whether they wanted to acknowledge it publicly or not.[citation needed]

Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo

Dizzy Gillespie, 1955

Mario Bauzá introduced bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie to Cuban conga drummer and composer Chano Pozo. Gillespie and Pozo's brief collaboration produced some of the most enduring Afro-Cuban jazz standards. "Manteca" (1947) is the first jazz standard to be rhythmically based on clave. According to Gillespie, Pozo composed the layered, contrapuntal guajeos (Afro-Cuban ostinatos) of the A section and the introduction, while Gillespie wrote the bridge. Gillespie recounted: "If I'd let it go like [Chano] wanted it, it would have been strictly Afro-Cuban all the way. There wouldn't have been a bridge. I thought I was writing an eight-bar bridge, but...I had to keep going and ended up writing a sixteen-bar bridge."[142] The bridge gave "Manteca" a typical jazz harmonic structure, setting the piece apart from Bauza's modal "Tanga" of a few years earlier.

Gillespie's collaboration with Pozo brought specific African-based rhythms into bebop. While pushing the boundaries of harmonic improvisation, cu-bop also drew from African rhythm. Jazz arrangements with a Latin A section and a swung B section, with all choruses swung during solos, became common practice with many Latin tunes of the jazz standard repertoire. This approach can be heard on pre-1980 recordings of "Manteca", "A Night in Tunisia", "Tin Tin Deo", and "On Green Dolphin Street".

African cross-rhythm

Mongo Santamaria (1969)

Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria first recorded his composition "Afro Blue" in 1959.[143]

"Afro Blue" was the first jazz standard built upon a typical African three-against-two (3:2) cross-rhythm, or hemiola.[144] The song begins with the bass repeatedly playing 6 cross-beats per each measure of 12/8, or 6 cross-beats per 4 main beats—6:4 (two cells of 3:2). The following example shows the original ostinato "Afro Blue" bass line; the slashed noteheads indicate the main beats (not bass notes), where you would normally tap your foot to keep time.

"Afro Blue" bass line, with main beats indicated by slashed noteheads.

When John Coltrane covered "Afro Blue" in 1963, he inverted the metric hierarchy, interpreting the tune as a 3/4 jazz waltz with duple cross-beats superimposed (2:3). Originally a B♭ pentatonic blues, Coltrane expanded the harmonic structure of "Afro Blue."

Perhaps the most respected Afro-cuban jazz combo of the late 1950s was vibraphonist Cal Tjader's band. Tjader had Mongo Santamaria, Armando Peraza, and Willie Bobo on his early recording dates.

Dixieland revival

In the late 1940s, there was a revival of Dixieland, harking back to the contrapuntal New Orleans style. This was driven in large part by record company reissues of jazz classics by the Oliver, Morton, and Armstrong bands of the 1930s. There were two types of musicians involved in the revival: the first group was made up of those who had begun their careers playing in the traditional style and were returning to it (or continuing what they had been playing all along), such as Bob Crosby's Bobcats, Max Kaminsky, Eddie Condon, and Wild Bill Davison.[145] Most of these players were originally Midwesterners, although there were a small number of New Orleans musicians involved. The second group of revivalists consisted of younger musicians, such as those in the Lu Watters band, Conrad Janis, and Ward Kimball and his Firehouse Five Plus Two Jazz Band. By the late 1940s, Louis Armstrong's Allstars band became a leading ensemble. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Dixieland was one of the most commercially popular jazz styles in the US, Europe, and Japan, although critics paid little attention to it.[145]

Cool jazz and West Coast jazz

Jazz at the Philharmonic announcement, 1956

In 1944, jazz impresario Norman Granz organized the first Jazz at the Philharmonic concert in Los Angeles, which helped make a star of Nat "King" Cole and Les Paul. In 1946, he founded Clef Records, discovering Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson in 1949, and merging Clef Records with his new label Verve Records in 1956, which advanced the career of Ella Fitzgerald et al.

By the end of the 1940s, the nervous energy and tension of bebop was replaced with a tendency toward calm and smoothness with the sounds of cool jazz, which favored long, linear melodic lines. It emerged in New York City and dominated jazz in the first half of the 1950s. The starting point was a collection of 1949 and 1950 singles by a nonet led by Miles Davis, released as the Birth of the Cool (1957). Later cool jazz recordings by musicians such as Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Bill Evans, Gil Evans, Stan Getz, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Gerry Mulligan usually had a lighter sound that avoided the aggressive tempos and harmonic abstraction of bebop.

Cool jazz later became strongly identified with the West Coast jazz scene, as typified by singers Chet Baker, Mel Tormé, and Anita O'Day, but it also had a particular resonance in Europe, especially Scandinavia, where figures such as baritone saxophonist Lars Gullin and pianist Bengt Hallberg emerged. The theoretical underpinnings of cool jazz were laid out by the Chicago pianist Lennie Tristano, and its influence stretches into such later developments as bossa nova, modal jazz, and even free jazz.

"Take The 'A' Train" This 1941 sample of Duke Ellington's signature tune is an example of the swing style. "Yardbird Suite" Excerpt from a saxophone solo by Charlie Parker. The fast, complex rhythms and substitute chords of bebop were important to the formation of jazz. "Mr. P.C." This hard blues by John Coltrane is an example of hard bop, a post-bebop style which is informed by gospel music, blues, and work songs. "Birds of Fire" This 1973 piece by the Mahavishnu Orchestra merges jazz improvisation and rock instrumentation into jazz fusion "The Jazzstep" This 2000 track by Courtney Pine shows how electronica and hip hop influences can be incorporated into modern jazz. | |

Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Hard bop

Hard bop is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music which incorporates influences from rhythm and blues, gospel music and blues, especially in the saxophone and piano playing. Hard bop was developed in the mid-1950s, coalescing in 1953 and 1954; it developed partly in response to the vogue for cool jazz in the early 1950s and paralleled the rise of rhythm and blues. Miles Davis' 1954 performance of "Walkin'" at the first Newport Jazz Festival announced the style to the jazz world.[146] The quintet Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, fronted by Blakey and featuring pianist Horace Silver and trumpeter Clifford Brown, were leaders in the hard bop movement along with Davis.

Modal jazz

Modal jazz is a development which began in the later 1950s which takes the mode, or musical scale, as the basis of musical structure and improvisation. Previously, a solo was meant to fit into a given chord progression, but with modal jazz, the soloist creates a melody using one (or a small number of) modes. The emphasis is thus shifted from harmony to melody:[147] "Historically, this caused a seismic shift among jazz musicians, away from thinking vertically (the chord), and towards a more horizontal approach (the scale),"[148] explained pianist Mark Levine.

The modal theory stems from a work by George Russell. Miles Davis introduced the concept to the greater jazz world with Kind of Blue (1959), an exploration of the possibilities of modal jazz which would become the best selling jazz album of all time. In contrast to Davis' earlier work with hard bop and its complex chord progression and improvisation, Kind of Blue was composed as a series of modal sketches in which the musicians were given scales that defined the parameters of their improvisation and style.[149]

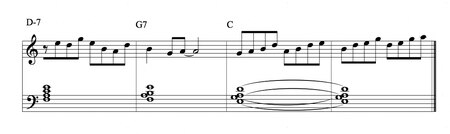

"I didn't write out the music for Kind of Blue, but brought in sketches for what everybody was supposed to play because I wanted a lot of spontaneity,"[150] recalled Davis. The track "So What" has only two chords: D-7 and E♭-7.[151]

Other innovators in this style include Jackie McLean,[152] and two of the musicians who had also played on Kind of Blue: John Coltrane and Bill Evans.

By the 1950s, Afro-Cuban jazz had been using modes for at least a decade, as much of it borrowed from Cuban popular dance forms which are structured around multiple ostinatos with only a few chords. A case in point is Mario Bauza's "Tanga" (1943), the first Afro-Cuban jazz piece. Machito's Afro-Cubans recorded modal tunes in the 1940s, featuring jazz soloists such as Howard McGhee, Brew Moore, Charlie Parker, and Flip Phillips. However, there is no evidence that Davis or other mainstream jazz musicians were influenced by the use of modes in Afro-Cuban jazz, or other branches of Latin jazz.[clarification needed]

Free jazz

John Coltrane, 1963

Free jazz, and the related form of avant-garde jazz, broke through into an open space of "free tonality" in which meter, beat, and formal symmetry all disappeared, and a range of world music from India, Africa, and Arabia were melded into an intense, even religiously ecstatic or orgiastic style of playing.[153] While loosely inspired by bebop, free jazz tunes gave players much more latitude; the loose harmony and tempo was deemed controversial when this approach was first developed. The bassist Charles Mingus is also frequently associated with the avant-garde in jazz, although his compositions draw from myriad styles and genres.

The first major stirrings came in the 1950s with the early work of Ornette Coleman (whose 1960 album Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation coined the term) and Cecil Taylor. In the 1960s, exponents included Albert Ayler, Gato Barbieri, Carla Bley, Don Cherry, Larry Coryell, John Coltrane, Bill Dixon, Jimmy Giuffre, Steve Lacy, Michael Mantler, Sun Ra, Roswell Rudd, Pharoah Sanders, and John Tchicai. In developing his late style, Coltrane was especially influenced by the dissonance of Ayler's trio with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray, a rhythm section honed with Cecil Taylor as leader. In November 1961, Coltrane played a gig at the Village Vanguard, which resulted in the classic Chasin' the 'Trane, which Down Beat magazine panned as "anti-jazz". On his 1961 tour of France, he was booed, but persevered, signing with the new Impulse! Records in 1960 and turning it into "the house that Trane built", while championing many younger free jazz musicians, notably Archie Shepp, who often played with trumpeter Bill Dixon, who organized the 4-day "October Revolution in Jazz" in Manhattan in 1964, the first free jazz festival.

A series of recordings with the Classic Quartet in the first half of 1965 show Coltrane's playing becoming increasingly abstract, with greater incorporation of devices like multiphonics, utilization of overtones, and playing in the altissimo register, as well as a mutated return to Coltrane's sheets of sound. In the studio, he all but abandoned his soprano to concentrate on the tenor saxophone. In addition, the quartet responded to the leader by playing with increasing freedom. The group's evolution can be traced through the recordings The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, Living Space and Transition (both June 1965), New Thing at Newport (July 1965), Sun Ship (August 1965), and First Meditations (September 1965).

In June 1965, Coltrane and 10 other musicians recorded Ascension, a 40-minute-long piece without breaks that included adventurous solos by young avante-garde musicians as well as Coltrane, and was controversial primarily for the collective improvisation sections that separated the solos. Dave Liebman later called it "the torch that lit the free jazz thing.". After recording with the quartet over the next few months, Coltrane invited Pharoah Sanders to join the band in September 1965. While Coltrane used over-blowing frequently as an emotional exclamation-point, Sanders would opt to overblow his entire solo, resulting in a constant screaming and screeching in the altissimo range of the instrument.

Free jazz in Europe

A shot from a 2006 performance by Peter Brötzmann, a key figure in European free jazz

Free jazz quickly found a foothold in Europe, in part because musicians such as Ayler, Taylor, Steve Lacy and Eric Dolphy spent extended periods there, and European musicians Michael Mantler, John Tchicai et al. traveled to the U.S. to experience American approaches firsthand. A distinctive European contemporary jazz (sometimes incorporating elements of free jazz but not limited to it) flourished because of the emergence of highly distinctive European or European-based musicians such as Peter Brötzmann, John Surman, Krzysztof Komeda, Zbigniew Namysłowski, Tomasz Stanko, Lars Gullin, Joe Harriott, Albert Mangelsdorff, Kenny Wheeler, Graham Collier, Michael Garrick and Mike Westbrook, who were anxious to develop new approaches reflecting their national and regional musical cultures and contexts. Since the 1960s, various creative centers of jazz have developed in Europe, such as the creative jazz scene in Amsterdam. Following the work of veteran drummer Han Bennink and pianist Misha Mengelberg, musicians started to explore free music by collectively improvising until a certain form (melody, rhythm, or even famous song) is found by the band. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead documented the free jazz scene in Amsterdam and some of its main exponents such as the ICP (Instant Composers Pool) orchestra in his book New Dutch Swing. Since the 1990s Keith Jarrett has been prominent in defending free jazz from criticism by traditionalists. British scholar Stuart Nicholson[154] has been prominent in arguing that European contemporary jazz's identity is now substantially independent of American jazz and follows a different trajectory.

Latin jazz

Latin jazz is the term used to describe jazz which employs Latin American rhythms and is generally understood to have a more specific meaning than simply jazz from Latin America. A more precise term might be Afro-Latin jazz, as the jazz subgenre typically employs rhythms that either have a direct analog in Africa or exhibit an African rhythmic influence beyond what is ordinarily heard in other jazz. The two main categories of Latin jazz are Afro-Cuban jazz and Brazilian jazz.

In the 1960s and 1970s, many jazz musicians had only a basic understanding of Cuban and Brazilian music, and jazz compositions which used Cuban or Brazilian elements were often referred to as "Latin tunes", with no distinction between a Cuban son montuno and a Brazilian bossa nova. Even as late as 2000, in Mark Gridley's Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, a bossa nova bass line is referred to as a "Latin bass figure."[155] It was not uncommon during the 1960s and 1970s to hear a conga playing a Cuban tumbao while the drumset and bass played a Brazilian bossa nova pattern. Many jazz standards such as "Manteca", "On Green Dolphin Street" and "Song for My Father" have a "Latin" A section and a swung B section. Typically, the band would only play an even-eighth "Latin" feel in the A section of the head and swing throughout all of the solos. Latin jazz specialists like Cal Tjader tended to be the exception. For example, on a 1959 live Tjader recording of "A Night in Tunisia", pianist Vince Guaraldi soloed through the entire form over an authentic mambo.[156]

Afro-Cuban jazz

Afro-Cuban jazz often uses Afro-Cuban instruments such as congas, timbales, güiro, and claves, combined with piano, double bass, etc. Afro-Cuban jazz began with Machito's Afro-Cubans in the early 1940s, but took off and entered the mainstream in the late 1940s when bebop musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Taylor began experimenting with Cuban rhythms. Mongo Santamaria and Cal Tjader further refined the genre in the late 1950s.

Although a great deal of Cuban-based Latin jazz is modal, Latin jazz is not always modal: it can be as harmonically expansive as post-bop jazz. For example, Tito Puente recorded an arrangement of "Giant Steps" done to an Afro-Cuban guaguancó. A Latin jazz piece may momentarily contract harmonically, as in the case of a percussion solo over a one or two-chord piano guajeo.

Guajeos

Guajeo is the name for the typical Afro-Cuban ostinato melodies which are commonly used motifs in Latin jazz compositions. They originated in the genre known as son. Guajeos provide a rhythmic and melodic framework that may be varied within certain parameters, whilst still maintaining a repetitive - and thus "danceable" - structure. Most guajeos are rhythmically based on clave (rhythm).

Guajeos are one of the most important elements of the vocabulary of Afro-Cuban descarga (jazz-inspired instrumental jams), providing a means of tension and resolution and a sense of forward momentum, within a relatively simple harmonic structure. The use of multiple, contrapuntal guajeos in Latin jazz facilitates simultaneous collective improvisation based on theme variation. In a way, this polyphonic texture is reminiscent of the original New Orleans style of jazz.

Afro-Cuban jazz renaissance

For most of its history, Afro-Cuban jazz had been a matter of superimposing jazz phrasing over Cuban rhythms. But by the end of the 1970s, a new generation of New York City musicians had emerged who were fluent in both salsa dance music and jazz, leading to a new level of integration of jazz and Cuban rhythms. This era of creativity and vitality is best represented by the Gonzalez brothers Jerry (congas and trumpet) and Andy (bass).[157] During 1974–1976, they were members of one of Eddie Palmieri's most experimental salsa groups: salsa was the medium, but Palmieri was stretching the form in new ways. He incorporated parallel fourths, with McCoy Tyner-type vamps. The innovations of Palmieri, the Gonzalez brothers and others led to an Afro-Cuban jazz renaissance in New York City.

This occurred in parallel with developments in Cuba[158] The first Cuban band of this new wave was Irakere. Their "Chékere-son" (1976) introduced a style of "Cubanized" bebop-flavored horn lines that departed from the more angular guajeo-based lines which were typical of Cuban popular music and Latin jazz up until that time. It was based on Charlie Parker's composition "Billie's Bounce", jumbled together in a way that fused clave and bebop horn lines.[159] In spite of the ambivalence of some band members towards Irakere's Afro-Cuban folkloric / jazz fusion, their experiments forever changed Cuban jazz: their innovations are still heard in the high level of harmonic and rhythmic complexity in Cuban jazz and in the jazzy and complex contemporary form of popular dance music known as timba.

Afro-Brazilian jazz

Naná Vasconcelos playing the Afro-Brazilian Berimbau

Brazilian jazz such as bossa nova is derived from samba, with influences from jazz and other 20th-century classical and popular music styles. Bossa is generally moderately paced, with melodies sung in Portuguese or English, whilst the related term jazz-samba describes an adaptation of street samba into jazz.

The bossa nova style was pioneered by Brazilians João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim and was made popular by Elizete Cardoso's recording of "Chega de Saudade" on the Canção do Amor Demais LP. Gilberto's initial releases, and the 1959 film Black Orpheus, achieved significant popularity in Latin America; this spread to North America via visiting American jazz musicians. The resulting recordings by Charlie Byrd and Stan Getz cemented bossa nova's popularity and led to a worldwide boom, with 1963's Getz/Gilberto, numerous recordings by famous jazz performers such as Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra, and the eventual entrenchment of the bossa nova style as a lasting influence in world music.

Brazilian percussionists such as Airto Moreira and Naná Vasconcelos also influenced jazz internationally by introducing Afro-Brazilian folkloric instruments and rhythms into a wide variety of jazz styles, thus attracting a greater audience to them.[160][161][162]

Post-bop

Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival with Marc Johnson on bass and Philly Joe Jones on drums, July 13, 1978