Real Academia de la Historia

| Royal Academy of History | |

|---|---|

Native name Spanish: Real Academia de la Historia  | |

| |

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°24′48″N 3°41′56″W / 40.413466°N 3.698992°W / 40.413466; -3.698992Coordinates: 40°24′48″N 3°41′56″W / 40.413466°N 3.698992°W / 40.413466; -3.698992 |

| Architect | Juan de Villanueva |

Spanish Property of Cultural Interest | |

| Official name: Real Academia de la Historia | |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1945 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001170 |

Location of Royal Academy of History in Spain | |

Real Academia de la Historia (English: Royal Academy of History) is a Spanish institution based in Madrid that studies history "ancient and modern, political, civil, ecclesiastical, military, scientific, of letters and arts, that is to say, the different branches of life, of civilisation, and of the culture of the Spanish people". The Academy was established by royal decree of Philip V of Spain on 18 April 1738.[1]

Contents

1 Building

2 Collections

3 Criticism

4 Biographical work

4.1 Biographical dictionary

4.2 Metro collaboration

5 Members

6 Academic correspondents

7 References

8 External links

Building

Since 1836 the Academy has occupied an 18th-century building designed by the neoclassical architect Juan de Villanueva. The building was originally occupied by the Hieronymites, a religious order. It become available as a result of legislation in the 1830s confiscating monastic properties (the ecclesiastical confiscations of Mendizábal).[2]

Collections

As formerly the main Spanish institution for antiquaries, the Academy retains significant libraries and collections of antiquities, which cannot be seen by the public. The keeper of antiquities is the prehistorian Martín Almagro Gorbea.[3]

Items held include:

- The Glosas Emilianenses

- The Códice de Roda

- The San Millán Beatus

- The Missorium of Theodosius I, a large ceremonial silver dish, probably made in Constantinople for the tenth anniversary (decennalia) in 388 of the reign of the Emperor Theodosius I, the last Emperor to rule both the Eastern and Western Empires. It is one of the best surviving examples of Late Antique Imperial imagery and one of finest examples of late Roman goldsmith work.

Criticism

Some Spanish historians have considered it an obsolete misogynist institution, that still considers history as a matter of kings and battles.[4][5]

However, the image has changed since Carmen Iglesias, the first woman director, took over from Gonzalo Anes.[6] By some authors RAH is considered "thoroughly undemocratic" institution "unrepresentative of Spanish historical profession" and a hotbed of historical revisionism.[7]

Biographical work

Biographical dictionary

In 2011 the Academy published the first 20 volumes of a dictionary of national biography, the Diccionario Biográfico Español, to which some five thousand historians contributed. The publicly funded publication has been subject of controversy for failing to achieve the standards of objectivity associated with, for example, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. The British Dictionary restricted itself to persons who were deceased, and the historian Henry Kamen has argued that it was a mistake for its Spanish equivalent to include living figures among entries.[8] However, while there was criticism of entries for some living people (such as the politician Esperanza Aguirre), the main allegations of bias concern articles relating to Francoist Spain. A notable example was the entry on Francisco Franco, written by Luis Suárez Fernández, in which Franco is defined as an autocratic head of state rather than a dictator.[4][9] In contrast, the administration of the democratically elected President Negrín is described as dictatorial.[10]

The dictionary sparked an outcry. Most objections came from voices on the left such as the party United Left and the newspaper Público.[10] For his part, Green party senator Joan Saura asked for publication of the dictionary to be stopped and the offending volumes withdrawn.[11] There was also a call for corrections from the Ministry of Education. The Academy announced in June 2011 that amendments would be made to the text on line and in future paper editions.[12] In 2012, when the Minister of Education, Culture and Sport, made a statement on the subject of the dictionary, it was still not clear whether the Academy was willing to describe Franco as a dictator.[13] However, by 2015 with Carmen Iglesias as director, the situation had changed.[14] In 2018 a ceremony was held at El Pardo to launch the online edition, Diccionario Biografico Electronico.[15] Press reports noted that Franco's status as a dictator was confirmed.[16]

Metro collaboration

In 2015 the Academy entered into an initiative in collaboration with Metro de Madrid to provide information about people who have given their names to metro stations.[17]

Members

Per article 6 of its statutes, the Real Academia de la Historia is composed of a maximum of 36 "Numbered Academics" who must be Spanish citizens. There are also Academics of Honor and Academic Correspondents, who may be of any nationality.[18] The Director since 2014 has been Carmen Iglesias.[19]

The Numbered Academics are (after the number of chair):[20]

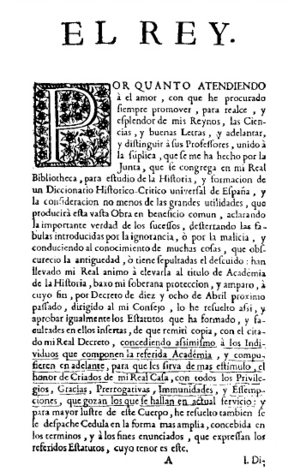

Royal approval of the first statute of the Real Academia de la Historia 17 June 1738

- Vicente Pérez Moreda

- Hugo O'Donnell y Duque de Estrada

- Francisco Rodríguez Adrados

- Luis Suárez Fernández

- Feliciano Barrios Pintado

- Pedro Tedde de Lorca

- Josefina Gómez Mendoza

- José Remesal Rodríguez

- María del Pilar León-Castro Alonso

- Vacant

- Martín Almagro Gorbea

- Carlos Seco Serrano

- Jaime Salazar y Acha

- Francisco Javier Puerto Sarmiento

- Juan Pablo Fusi Aizpurúa

- Antonio Cañizares Llovera

- Vacant

- José Antonio Escudero López

- Luis Antonio Ribot García

- Fernando Díaz Esteban

- José Ángel Sesma Muñoz

- Enriqueta Vila Vilar

- María del Carmen Iglesias Cano

- Fernando Marías Franco

- Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada

- Serafín Fanjul García

- Miguel Ángel Ochoa Brun

- Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Prado

- José Luis Díez García

- Carmen Sanz Ayán

- Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués

- Carlos Martínez Shaw

- María Jesús Viguera Molins

- Miguel Artola Gallego

- Xavier Gil Puyol

- Luis Agustín García Moreno

Academic correspondents

Notable Academic Correspondents of the Academy include:

- Sir Raymond Carr (1919–2015)

References

^ Kagan, Richard L. (29 December 2010). Clio and the Crown: The Politics of History in Medieval and Early Modern Spain. JHU Press. p. 279. ISBN 9781421401652. Retrieved 16 April 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Mateos Gómez, Isabel; López-Yarto Elizalde, Amelia; Prados García, José (1 January 1999). El arte de la orden jerónima (in Spanish). Encuentro. p. 43. ISBN 9788474905526.

^ "D. Martín ALMAGRO GORBEA" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

^ ab Marcos, J. M. and Corroto, P. and Jaén, B. García "Los historiadores se alarman ante la hagiografía de Franco" in Público, 30 May 2011

^ María Pilar Queralt del Hierro, "Mujer, historia y Academia: incompatibles para Gonzalo Anes". 2011

^ Anes was initially replaced by Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués.

^ Chris Ealham, The Emperor's New Clothes: 'Objectivity' and Revisionism in Spanish History, [in:] Journal of Contemporary History 48/1 (2012), p. 192

^ Kamen, Henry (2011). "La ideología política y el Diccionario Biográfico". (subscription required)

^ Natalia Junquera (2011), Francoism isn't over in Spain, El País (English edition)

^ ab La Real Academia de la Historia 'no corregirá' la polémica biografía de Franco, El Mundo

^ "ICV insta a retirar los primeros 25 tomos del Diccionario Biográfico in Público, 30 May 2011

^ La Academia de Historia corregirá la entrada de Franco..., ABC

^ "Wert: 30 entradas". Público. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

^ Francisco Franco was a dictator after all, Royal History Academy concludes El País (English edition)

^ "La historia se conecta".

^ Morales, Manuel (3 May 2018). "El 'Diccionario Biográfico Español' se enmienda en la Red". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

^ "Correspondencia con la Historia" (in Spanish). RAH.

^ "Estatutos" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

^ "Mª del Carmen Iglesias Cano, Condesa de Gisbert" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

^ "Académicos Numerarios" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Real Academia de la Historia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Real Academia de la Historia at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website